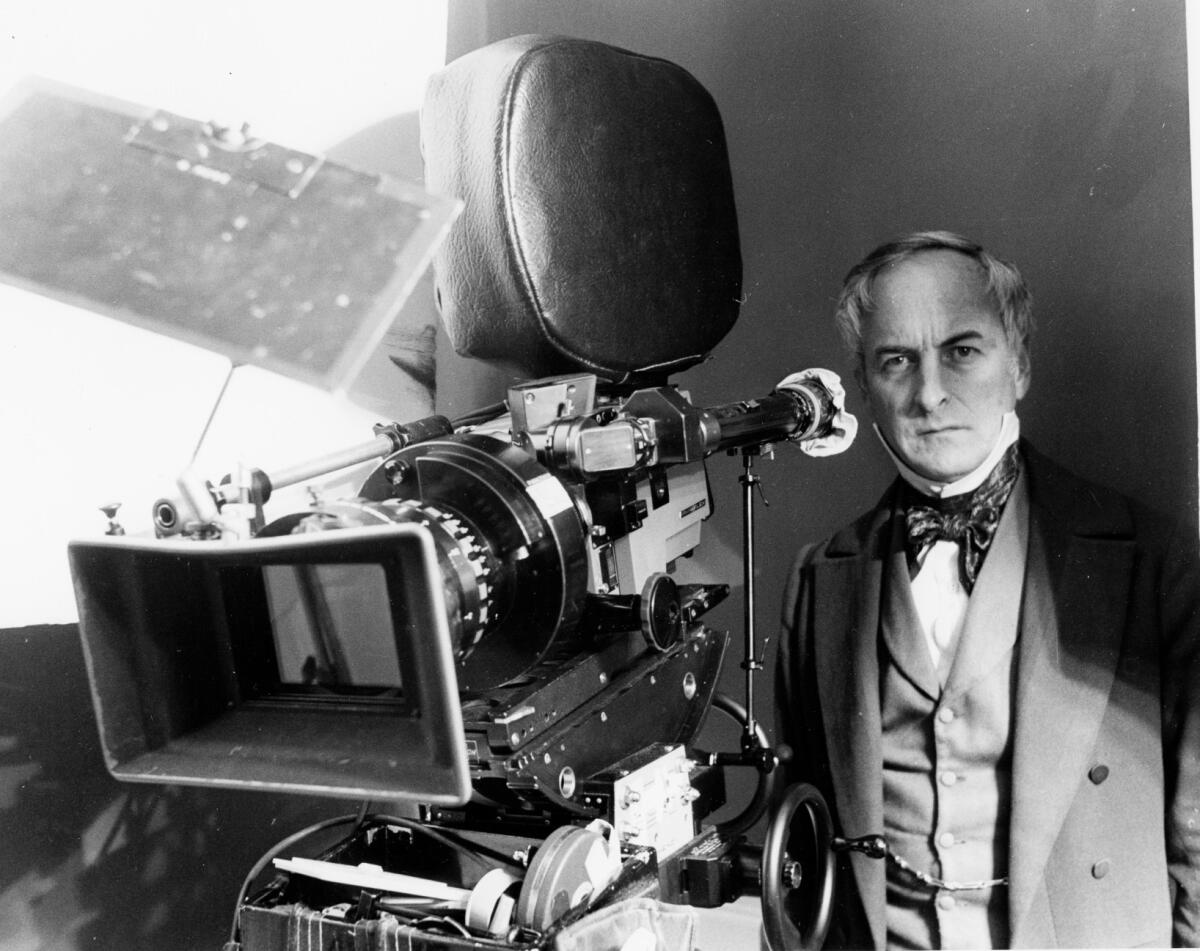

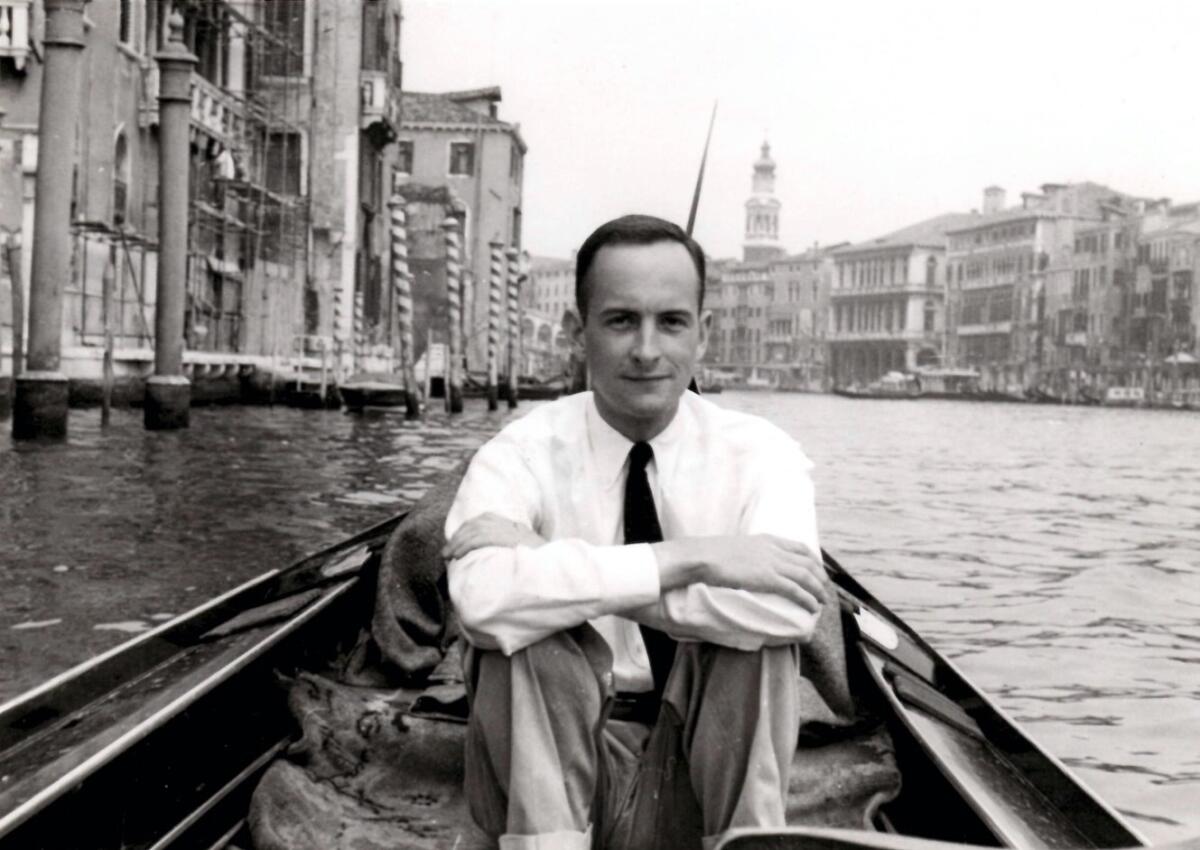

Cinema legend James Ivory, 93, talks about letting it all hang out — and more

- Share via

Over the course of more than two dozen movies, filmmaker James Ivory became best known for his decades-long collaboration with producer Ismail Merchant and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala on literate, restrained, lushly upscale pictures such as “A Room With a View,” “The Remains of the Day” and “Howard’s End.” Yet there is more to James Ivory than the Merchant-Ivory stereotype (itself a reduction of a widely varied body of work that includes early films in India such as “Shakespeare Wallah” and “Bombay Talkie”).

Now 93, Ivory has just published “Solid Ivory,” a memoir edited by Peter Cameron that collects decades of writing, much of it never intended for publication. He recalls his early years growing up in Oregon, his time at USC film school and his life with Merchant as a team and a couple.

The book gradually builds momentum toward emotional pieces written for the book — portraits of Merchant and Jhabvala that capture their irreplaceable dynamic. (Merchant died in 2005, Jhabvala in 2013.) The other new piece in the collection explores Ivory’s work on the 2017 film “Call Me By Your Name,” which earned him the Oscar for adapted screenplay at 89, making him the oldest-ever Academy Award winner. From his home in upstate New York, Ivory spoke to The Times last week about his work, his writing and his memory in a conversation that has been edited and condensed.

In particular through your early years, your memories are so specific and so vivid. You remember what you ate the day you first saw a movie at age 5.

Well, I do remember those kinds of things. I don’t know why. Maybe that’s a flaw of character that I remember those kinds of unimportant things. I do remember that spot on my shirt right on the front, and it must have been gravy from the roast beef that we’d had. And mashed potatoes.

The book is filled with so many great moments and images involving everyone from Pauline Kael and Satyajit Ray and George Cukor to J.D. Salinger.

Well, I’m also a film director and moments are my big thing. Where would I be unless I collected a lot of moments and thought about them?

You also have a lyrical way of describing other men’s penises. The New York Times review of the book likened it to notes on fine wines.

Let me tell you something funny that I’ve been noticing in these reviews. It seems to be the women writers who notice that more than the men wish to discuss it. I don’t know what that is. Is that what we call prurience? I really don’t know.

What made you want to include that?

That was specifically about three or four different guys that I was very close to. You don’t get such descriptions of all my friends. If you’re writing in private about your sexual relations with anybody, whether it’s a man and a woman or two men or two women or whatever it is, you just write it. There’s no inhibitions. I never supposed these things were ever going to be published. It’s part of what you remember, like the mashed potatoes and gravy stain on my shirt. And I wasn’t then going to censor these things, particularly these days.

You describe your long relationship with Ismail Merchant as an open one. How did the two of you make that work? Combining your working lives and your personal lives must have been complicated.

Neither of us was going to throw away what was most important to us in our life. What was most important was our filmmaking together. Usually when somebody kind of came into our life from outside, they were put to work. I can’t think of a single guy Ismail took up that didn’t eventually go to work for Merchant Ivory. And sometimes to my benefit. Richard Robbins, he was a wonderful composer. And something of a musicologist, which was important because we did period films.

When he died, or when he couldn’t work anymore, it was terrible. Ruth and I didn’t know what we were going to do. By this time Ismail had died, Dick had Parkinson’s disease. He tried to work on “The City of Your Final Destination,” but he would work on it for a whole day and then the next day he’d spend that whole day correcting the mistakes he’d made. I came to feel that our films without his music were just not Merchant Ivory movies.

And what to you was special about the work you, Ruth and Ismail did together?

It was like the American government; you needed those three different agencies to make it all run. You had to have a president, you had to have a Congress and you had to have a Supreme Court. Ismail got the whole machine going, as Congress does. And I was pretty much the boss deciding what films he would do or not do. And Ruth was writing the films, but sometimes she didn’t like a particular project and then we didn’t make them, or we made them apart from her.

In the book you are very candid about your difficulties working on “Call Me By Your Name” and the falling out you had with director Luca Guadagnino. Was the screenplay Oscar bittersweet?

Not really. I mean, here’s the thing: I thought I was going to be directing it with him, but I knew that would be difficult because to have two directors on a set, it’s almost never done. And also the Directors Guild forbids it. What if you’re shooting a scene and then you get into a dispute with the other director and one of them has to give way? I never felt that that was going to be a workable thing and it didn’t come to pass. So it wasn’t as if I terribly regretted not being a co-director. But at the point when I thought I was going to be a co-director, I said, well, I have to have my own script. Because there had been a script before that, and I wasn’t thinking it did the book justice. So they said fine. And so on spec, I wrote it and then turned it in and everybody liked it. And then they were able to raise money and do it. And at a certain point it seemed they didn’t want me around. Simple as that. I can understand that; I would have been the same way.

When you look back on your life now, what stands out most for you?

I don’t want to sound smug or anything, but I do feel a certain satisfaction that I was able all my life to do really what I wanted to do, which was make films and make films with Ismail. And then, well, I have lived a life of comfort. There’s no doubt about it. And I’m glad about that. I mean, particularly now that I’m an old man.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.