How can we stop treating children of color like criminals? One step at a time, a lawyer says

- Share via

On the Shelf

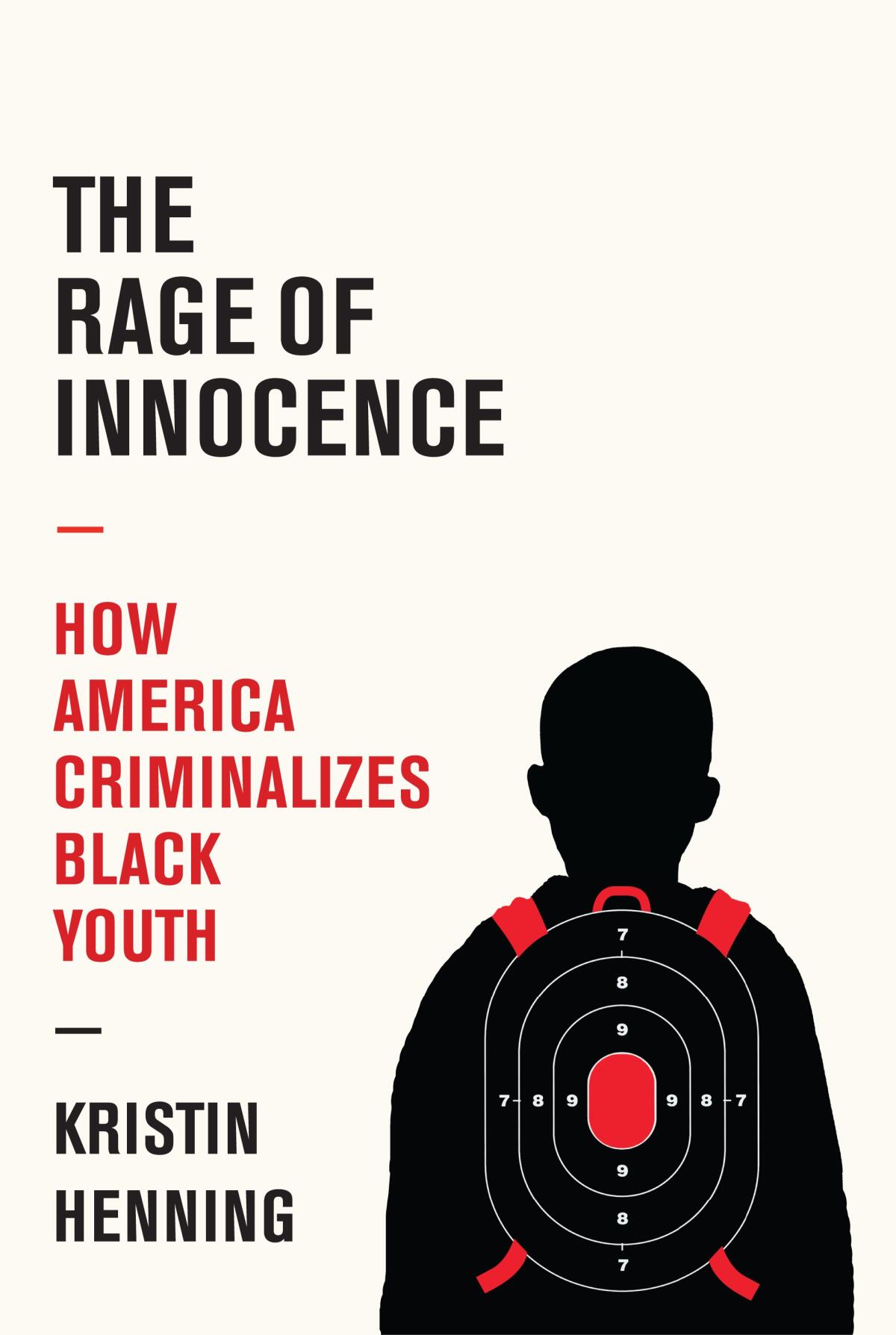

The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth

Kristin Henning

Pantheon: 521 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Kristin Henning used to think that the aggressive presence of heavily armed police in American schools was a reaction to the epidemic of school shootings. The timing was right: There were 9,400 “school resource officers” nationally in 1997, before Columbine; by 2016 there were at least 27,000.

But Henning, a lawyer in Washington, D.C., who has represented Black youth for a quarter-century, also knew cops tended to target and physically mistreat students of color; whatever profiling was going on, it had little to do with the demographics of school shooters. So she dug deeper and found a much earlier accelerator of police presence: integration.

“As we think about reform we need to understand the past,” Henning says. “We have to think hard about how we got here.”

Henning’s new book, “The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth,” blends history, data, anecdotes and adolescent brain science to lay out the case that when it comes to school policing, we have it exactly backward.

“The average person isn’t even cognizant of the implicit ways in which Black children are treated differently and criminalized,” she says. When a child is singled out this way, it can often become self-fulfilling: “It’s human nature to feel rejected and it starts a vicious cycle where you’ll distrust authority.” The result, she says, is “empirically supported by facts”: Overpolicing leads to an increase in crime.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

Even so, she argues that most criminal charges against Black youth are trumped up. “The vast majority — 80 percent or more — of crimes committed by children are non-serious crimes,” she says. “We could reduce law enforcement engagement with young people by 80 percent and we would all be fine, but people don’t believe that.”

Henning, who leads workshops for prosecutors, judges, defenders and others around racial justice and the legal system, spoke with The Times about the worst of the outrages and the glimmers of hope.

Do you find it surprising that you still must explain your humanity to your fellow Americans?

I am still shocked and outraged that people do not accept what is unequivocally true, which is that Black children are children too. We know more about the adolescent brain and adolescent psychology than ever before, yet we still don’t change. Adolescents all over the world engage in the same impulsive, peer-influenced, sensation-seeking behaviors that your own kids do and that you did as a kid. Yet we still see racial disparities in the ways we respond to normal behavior by Black children.

Was writing the book an upsetting experience?

On my computer are files going back for years, a collection of cases that were ridiculous, so it’s been in my heart and my gut for a long time. But then I forced myself to watch documentaries and interviews with mothers and fathers who have lost Black children, Trayvon Martin’s family, Tamir Rice’s, Mike Brown’s. Reliving those stories was so painful, I would have nightmares while writing; I was much more emotional than I ever thought I’d be.

Why is it important to understand the way puberty has started earlier for poor children, especially Black and brown children?

It’s about getting people to see a young person in that face as opposed to physical features of breasts or height or weight. There’s an intersection between the racial bias and adultification — you almost now have an excuse not to see them as children. Tamir Rice was big, but he was a child.

You spent a lot of time on the less extreme cases — and the lasting trauma of being constantly frisked or arrested.

The trauma portion was essential to include; the research on the impact of trauma on people of color but especially adolescents was mind-boggling. I see it when I talk to young people, but when you tie the research to it you see how it’s a much larger issue. There’s body camera footage from the police where officers walk into a neighborhood and four or five Black and brown kids will just lift their shirts to expose their waistband [to show they have no gun] without even being asked. That’s a state of trauma and that’s not known at all.

Salaam, one of the five convicted in 1989 for a crime they didn’t commit, collaborated with author Ibi Zoboi on the verse novel “Punching the Air.”

People are probably more aware of street harassment, but you devote a lot of time to the dangers of implicit bias deep inside schools.

School is supposed to be a safe space. Studies show it is even more embarrassing to get stopped by police in school than on the street, and it builds distrust of authority. The school system has become an extension of the criminal legal system. Principals become the wardens; teachers become the guards.

The strongest resistance to change comes from police unions. Does that frustrate you?

They’re the ones resistant to reform. It’s critically important in dealing with adolescents to reduce swagger. I’d want to ask officers, “How are you in an ego battle with a 13- year-old?” Kids haven’t yet learned to express themselves and sometimes they don’t even know what they’re feeling. We have to get officers to remember what they were like as teenager and say, “You’re the adult and you need to act like one.”

But you make the point that many officers don’t see them as children.

Part of my goal is to shift the narrative, to help people break that blind spot of bias, but it’s going to take work. I wish we could change minds and attitudes but sometimes you have to change the techniques first. Create minimal standards or requirements — like no use of force on adolescents, no weapons for officers in schools or on playgrounds. With ideas like that you can gradually better relationships.

Are there any signs of progress?

In 2000, the Supreme Court case of Illinois vs. Wardlow said that flight from the police is appropriately interpreted as consciousness of guilt. So if a teen has been stopped before or is just nervous and he runs, then the police has the right to presume them guilty of a crime. But since 2015, a number of state high courts have been slowly rolling back that decision.

The problems cannot be solved entirely by the law, but this is important. What seems like tinkering around the edges is opening the door to incredibly important conversations about the meaning of race and trauma in the law. If we have a law that prohibits police officers from asking a child to lift their shirt or to consent to a frisk, that might be one less child in the system. The cumulative effects of those little pieces have major impacts.

Advocates of police reform are upset about the delays in removing the LAPD from traffic enforcement. They fear their cause may lose steam.

Are you hopeful because of the changes you see or despairing because so many still need to be made?

I can’t let myself despair too much or the work becomes overwhelming. We have to work on saving one kid at a time, changing one state at a time, one law at a time. Keep your eye on the daily prize and hope that in the end it gets us closer to where we need to be. I don’t think in my lifetime I’ll see the kind of change we really need, but I think I will see the moral arc bending toward justice.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.