Review: Larry Elder complained we’d never reviewed his books. So we did, like it or not

- Share via

On the Shelf

Larry Elders' Oeuvre

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Let me begin with a confession. Until July, when he announced as a candidate in California’s gubernatorial recall election, I’d never given Larry Elder a lot of thought. Sure, I knew who he was (how could I not?): conservative radio and television host, vocal supporter of Donald Trump. But I don’t have much use for the hot takes of self-styled pundits, who are mostly interested in serving themselves.

Among Elder’s complaints about the mainstream media is one he repeated in a recent interview with The Times — that the paper has never reviewed his books. The underlying assumption — the talking point, if you will — is that the press isn’t open-minded enough to take conservative arguments seriously.

But what if those arguments are themselves not serious? In the interest of critical discourse, I decided to find out.

Elder is the author of seven books, the majority of which collect columns and commentary that are, at best, specious, both intellectually and politically. This past week I read four of them — “Showdown: Confronting Bias, Lies, and the Special Interests That Divide America” (2003), “Double Standards: The Selective Outrage of the Left” (2017), “A Lot Like Me: A Father and Son’s Journey to Reconciliation” (2018) and “The New Trump Standard” (2019). These books are nothing if not consistent, recycling the same outrage over the same issues, the same straw men (FDR, JFK, the Clintons) and supporting arguments. (He has a particular fondness for Milton Friedman and Thomas Sowell.)

On the most basic level, this makes sense, for Elder is not a writer but a brand. As such, he is always on brand, regardless of the issue: the economy, the unhoused, law enforcement, immigration rights. His columns represent not so much a voice in conversation as a series of diatribes. When it comes to public policy, Elder offers neither subtlety nor nuance, not least because that isn’t what his audience wants.

Take, for instance, the section on healthcare in “Showdown.” There, Elder derides the benefits of preventive medicine despite the financial sense it makes. “But even if money spent now saves money later, so what?” he fulminates. “Why do taxpayers foot the bill for health care for other people at all?”

This is a standard-issue libertarian argument, but Elder lacks the evidence — or perhaps the interest — to make that case. Instead, he falls back on scattershot observations about Canada and Great Britain and their national health programs before concluding that the real problem with “[t]third-party paying systems” is that they “condition people into not thinking about the cost of health care.”

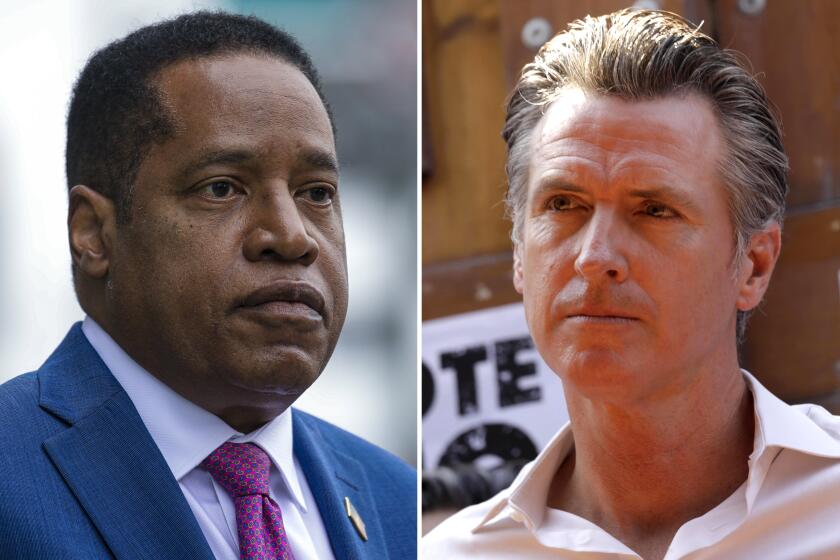

Conservative talk show host Larry Elder has emerged as the Republican front-runner in the race to replace Gavin Newsom if voters recall the governor.

Think about that for a moment. The implication is that if we don’t have to worry over the price of doctor visits or treatment, we will abuse our access to them. “If the same system applied to food expenses,” he continues, quoting Mona Charen (whose columns are distributed by the same syndicate as Elder’s), “who wouldn’t choose filet mignon and caviar every night?”

People are children, in other words, unable to act responsibly on their own.

Such a perspective is not unlike the one Elder ascribes to the so-called nanny state, which he believes infantilizes people rather than allowing us to make decisions for ourselves. But don’t expect him to embrace, or even recognize, the irony.

He is equally inconsistent when it comes to education, although here, he himself provides the contradictory evidence. “Would parents, if they paid directly from their hard-earned salaries,” he asks, “tolerate the waste, poor discipline, and low academic standards that we see in inner-city public education?” This is why Elder favors vouchers and school choice; in an interview last month with CalMatters, he promised to appoint “somebody who has the same philosophy as … Betsy DeVos” to the state board of education. And yet, his own experience as a student at Crenshaw High School in the late 1960s complicates that simplistic point of view.

In his memoir, “A Lot Like Me,” Elder recalls taking advantage of “an experimental program called APEX — Area Program Enrichment Exchange” to spend a semester taking Spanish at Fairfax High School after he had exhausted Crenshaw’s offerings. “My first day of Spanish classes at Fairfax,” he recalls, “I was stunned at the level of competence. The teacher spoke only in Spanish. … Fairfax expected more from its students and, in turn, received more.”

What he’s describing is not a problem with parents. It’s unequal opportunity.

Here’s a look at The Times’ coverage of the California governor and the front-runner in the race to replace him should voters choose a recall.

“A Lot Like Me” may be the most interesting of Elder’s books — which is not to say it’s successful. Constructed around a conversation between the author and his father, Randolph, it moves in broad and blocky strokes to trace a sea change in the relationship of the two men from antipathy to a more abiding form of love.

Randolph Elder was a difficult parent: He raged and beat his three sons. At the same time, he was self-made, a survivor. Born in Georgia in 1915, he was on his own by age 13, served in the Marines during World War II and worked as a Pullman porter before opening a diner in Pico-Union.

Elder is a survivor also, albeit in a different way. After graduating from Crenshaw, he attended Brown University (an early beneficiary of affirmative action) and the University of Michigan Law School. He spent a decade estranged from his father before returning to Los Angeles for what he calls “The Talk”— an eight-hour conversation in the diner, during which the two men cleared the air.

“A Lot Like Me” recounts the story of this rapprochement. Although it’s meant to be inspiring, the narrative remains stilted and constrained. Why? Because it’s too expository, relying on a structure in which everything emerges via dialogue, pronouncements, another set of talking points. There is no space for doubt or questions, for uncertainty or the open-ended messiness of the human heart.

In that sense, “A Lot Like Me” is not unlike an extended version of one of Elder’s columns, operating out of an overly predetermined framework, as if 10 years of estrangement can be talked away in a single afternoon. There’s no surprise, no sense of discovery. Everything unfolds exactly as the author believes it should.

Woodward’s journalism helped bring down Richard Nixon. But “Rage” it too ploddingly neutral and enamored of access to make a dent in this fallen age.

This is important because it suggests something about how Elder might govern. It suggests something about his brand. If it can be useful to know one’s own mind, we also need leaders who are flexible, who have the ability to listen and adapt. Leadership is not a top-down activity; rather, it’s a collaborative one.

Elder is not a collaborator. He’s never had to be. He plans to govern using legally dubious emergency declarations to terminate “bad” teachers and upend California’s Environmental Quality Act. The criteria are subjective and unclear. These are not policies, they are provocations. But then, provocation is Elder’s métier. Why else promise to suspend mask and vaccine mandates that have been essential to California’s success in mitigating the coronavirus pandemic? (Elder, it should be noted, is vaccinated.) Why else run for governor in the first place, when he’s acknowledged that he lacks the necessary temperament?

For an answer, let’s consider Elder’s forthcoming book, “Cancel the Left: 76 People Who Would Improve America by Leaving It,” scheduled to appear in June 2022. On the one hand, this seems like just another provocation, except for that publication date. The timing suggests Elder is thinking beyond the recall. Electoral politics is a brand-enhancing mechanism, in other words, as it was for the former president he so admires.

We all know what happened when people bought into that former president’s rhetoric of grievance. We’ve all experienced the havoc this has wrought. It has sundered us in ways that are intractable and complex — exposing rifts that cannot be reconciled in eight or even 8,000 hours of discussion. Such a reconciliation will require creativity and caution; it will be a process if it is achievable at all. Elder wants us to believe there are easy answers, but that’s just another branding exercise.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.