- Share via

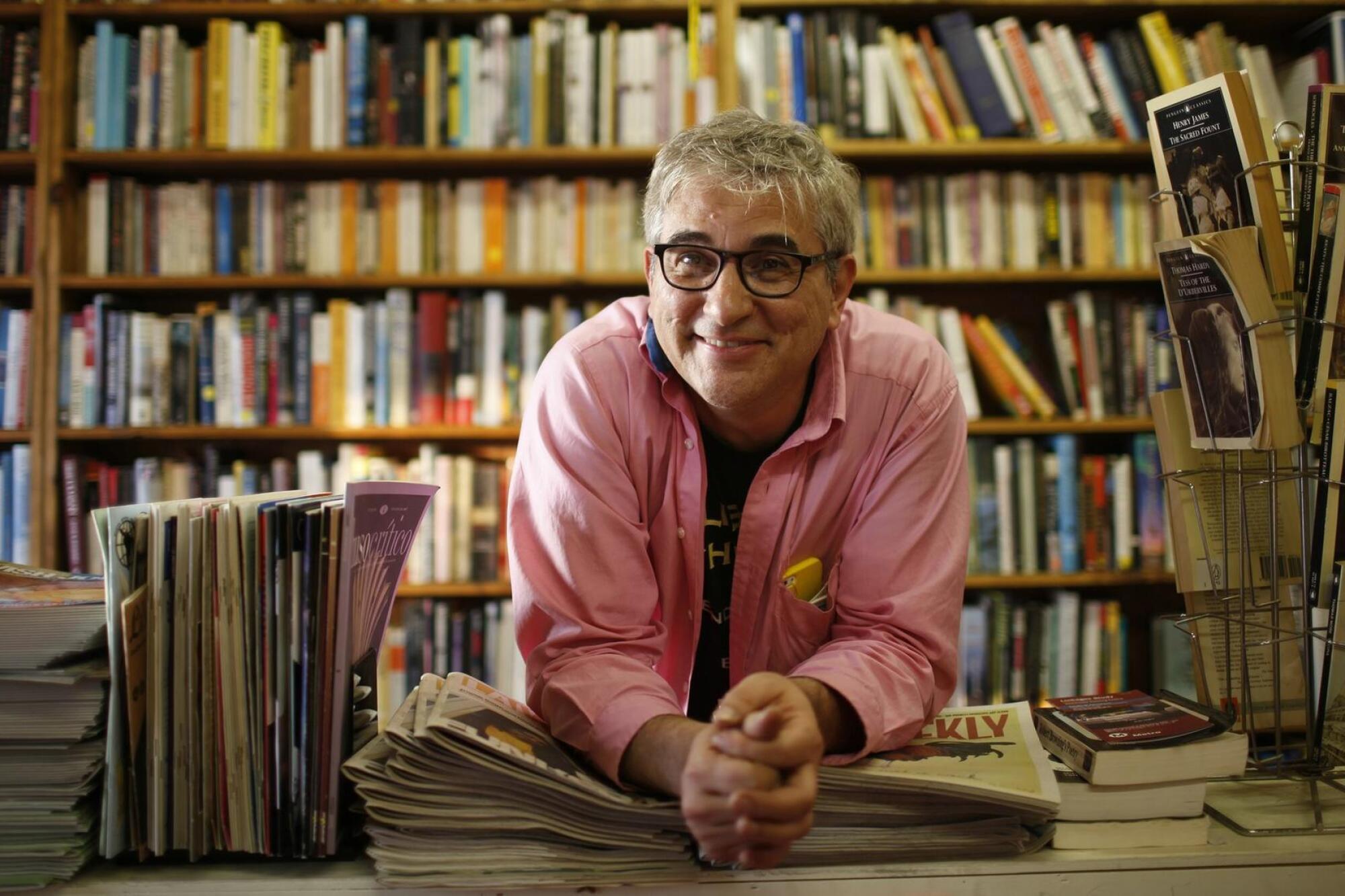

David Kipen is pretty sure the idea for a modern-day Federal Writers Project came to him at dawn.

It was early in the devastating spring of 2020 and the former literature director of the National Endowment for the Arts was thinking of his friends who’d died of COVID-19, a handful of the more than 578,000 people killed by the virus in the United States to date. He was thinking of his brilliant creative writing students at UCLA, deprived of internships and jobs. Of decimated small-town newspapers and fellow writers who’d been laid off. And he was thinking of the cosmic rifts dividing the nation.

“Then it hit me: America has been up this creek before,” Kipen recalled in an email interview with The Times. “And one way we saved ourselves was with the Federal Writers Project.”

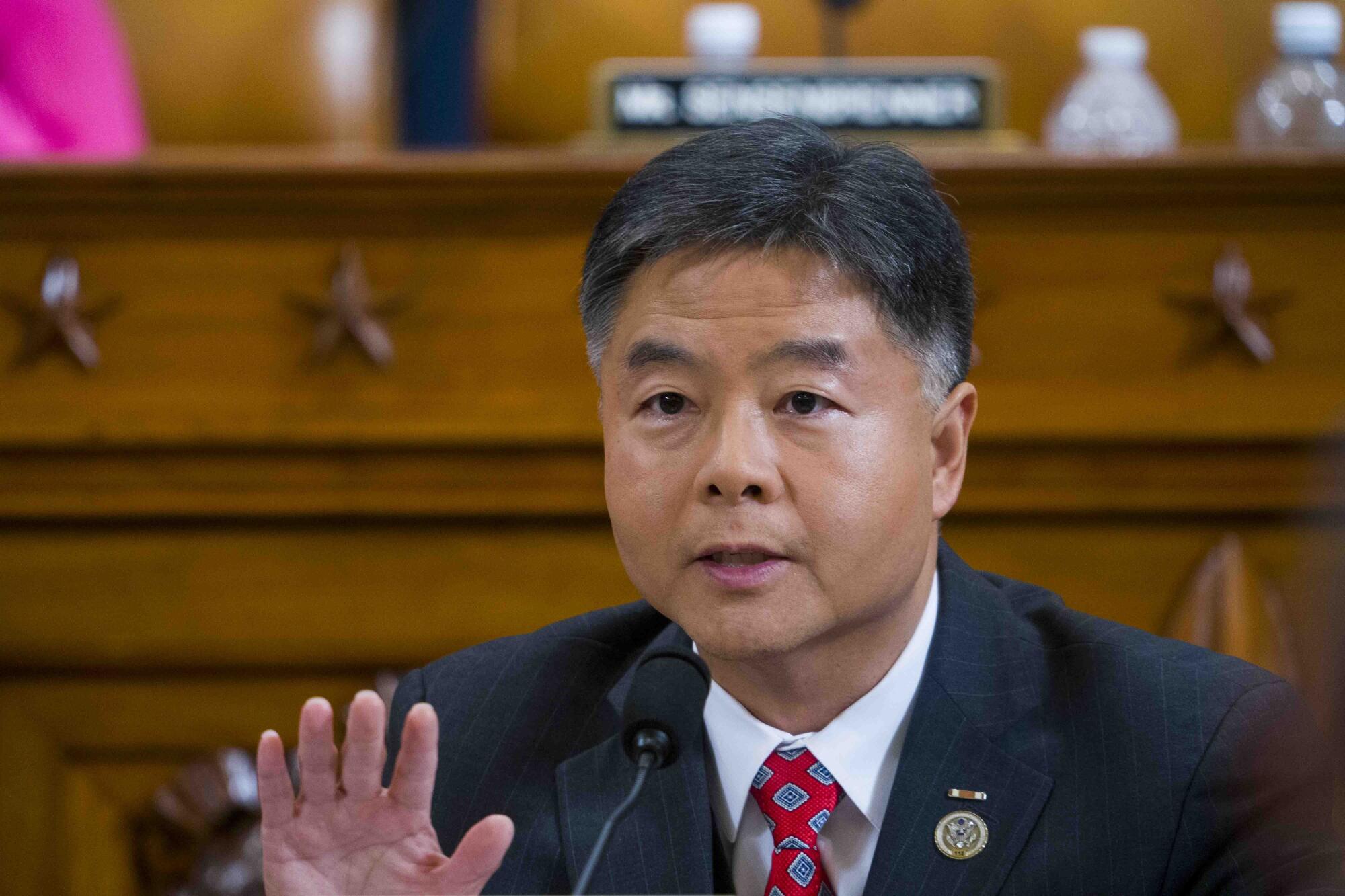

Like his forebears under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, Kipen rolled up his sleeves and went to work. He started writing letters to lawmakers calling for a revamped program for the COVID-19 era, and last May he wrote a piece for The Times examining that possibility. The article, headlined “85 years ago, FDR saved American writers. Could it ever happen again?,” piqued the attention of Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Torrance). Last summer, the congressman’s office began drafting a 21st century FWP — a grant program that would provide jobs for writers and other “cultural workers.”

On the anniversary of the birth of the Works Progress Administration, it’s worth asking what a post-COVID Federal Writers Project might look like.

The goal, said Lieu in an email to The Times, is to document the pandemic’s impact on American life, honor the lives lost to COVID-19, employ struggling writers and academics and create a national archive of work from our time, just as the original FWP left us with a rich collection of guidebooks and oral histories, including the first-person Slave Narratives.

The bill, titled the 21st Century Federal Writers’ Project, was introduced on Thursday. The project would entail $60 million administered by the Department of Labor to nonprofits, libraries, news outlets and communications unions, his office said.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated layoffs and position reductions at many news outlets, and many freelance and gig writers have also seen opportunities shrink away,” Lieu said.

“We can leverage their unique abilities to capture the drastic and unrelenting cultural shifts that are occurring throughout our nation due to the pandemic and the many years of cultural shift that will follow,” he added. “Not only will this program serve as a jobs program for many talented people, it will also supplement the national narrative and capture invaluable stories that may otherwise go untold.”

During the Great Depression as part of the New Deal, Roosevelt established the FWP with the goal of providing work for writers, historians, librarians, editors, teachers and others. At its peak, the program employed more than 6,000 people nationwide.

Gwendolyn Brooks, May Swenson, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, John Cheever and other major authors got their first writing gigs through the program. And just as important, by charting the impact of the Depression on individuals across the country, the FWP brought visibility to overlooked Americans during a period of extreme economic hardship.

As Ellison put it some three decades later to an audience at the New York Public Library, “You couldn’t find the truth about my background or my history” before the writers project. “You could not find the truth about other ethnic groups.”

So how did a dawn epiphany become a proposed bill? It took 1,002 “wheedling emails,” according to Kipen, most of them “sweated over, slept on, and reread in agony after hitting ‘send.’”

The idea has been steadily gaining support. David Shribman and Bill Knight wrote op-eds for the Boston Globe and the Canton Daily Ledger, respectively, arguing in favor of a revived program.

The Progressive Democrats of America became the first major organization to publicly support a new FWP. In a statement published April 19, the Washington-based PAC hailed the original project.

“We feel the social, and literary, benefits for the country of a new FWP will be as significant today as they were in the 1930s,” read the PDA’s statement.

Alan Minsky, the organization’s executive director, believes the benefits of a 21st century project would outweigh its cost.

“In terms of size of the whole federal budget, we’re not talking about a lot of money here, but that money can really go very far in making a huge and positive social impact,” Minsky said. “And it won’t be a small amount of money to the people in the communities that it helps.”

But June Hopkins, a retired history professor and granddaughter of WPA architect Harry Hopkins, isn’t kidding herself.

“[Lawmakers] are going to get a lot of blowback from people who say, ‘Why are you paying people to write? It’s not really a job, put them to work doing something useful,’” said Hopkins, who has been writing op-eds urging the Biden administration to adopt a 21st century New Deal. “Making the argument that this is useful work and this is important work, that’s the job that legislators have to prove.”

That job seems a lot easier than it did just a few months ago. In March, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, a $1.9-trillion COVID-19 relief bill that provides, among other things, $350 billion in aid to state and local governments and $335 million for museums, libraries and arts organizations. While the bill earned no Republican support, roughly 75% of Americans backed its passage, according to a public poll.

As the administration floats plans to spend trillions more in a country more sanguine about taxing and spending than it has been in a generation, a new FWP suddenly doesn’t seem so far-fetched.

In California, a similar bill has been in the works at the state level since April 2020.

Introduced by Sen. Benjamin Allen of the 26th District, the California Creative Work Force Act of 2021, or SB 628, would establish, among other things, a workforce to promote employment and provide job training for creative workers, including writers. The law, which passed unanimously through the Labor, Public Employment and Retirement committee last month, would be in the California labor code.

Julie Baker, executive director of Californians for the Arts, who helped develop the policy, emphasized the importance of telling stories during such a difficult time.

“We need to have this moment to reflect,” said Baker, “and artists are who we look to for the meaning, for the hope, for the clarity, for this cohesion, this sense of belonging — this sense of, How do we come out of this?”

Jason Boog can tell you firsthand about the struggles of writers in the 21st century. During the 2008 recession, he lost his job when the publication he worked for, Judicial Reports, shut down. For freelance writing gigs, he used the New York University library as his office, and when he wasn’t writing, he was reading.

Intrigued by the challenges of his forebears in unemployment, Boog began pitching pieces about writers during the Great Depression. Twelve years later (by which point he was the West Coast correspondent for Publishers Weekly), he collected them into his own book, published last year: “The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today.”

Reading about the Depression during the Great Recession had given Boog hope amid profound stress and uncertainty. He’d even entertained the idea of federal intervention to help thousands of writers who, like him, had been laid off from steady jobs.

Help didn’t come in 2008, but then came the pandemic — truly a once-in-a-lifetime cataclysm. It felt to him like a possible sea change. But the long wait and the lessons of history have also made him realistic. “The sad and hard lesson that I learned from the Great Depression is that it takes a long time to recover from this,” Boog said, “and it takes a long time to make meaningful changes.”

Even if Lieu’s bill advances, a lot would have to happen for it to become law. A House committee would research and tweak the bill before it could be sent to the House floor, further discussed and tweaked and voted on before being sent to the Senate. With a divided Senate, the chances of the bill passing — barring a larger Democratic takeover or a demolition of the filibuster — aren’t good.

Yet on the eve of the bill’s introduction, Lieu was optimistic. “We have an opportunity to not only employ a lot of people but also to document all the different stories,” he said in an phone interview, “to make sure we record — while it’s fresh in peoples minds — what’s transpired during this pandemic. And I think that is something that can get bipartisan support.”

Whatever happens, he hopes introducing the bill accomplishes two things: reminding lawmakers how successful the original FWP was and highlighting the “importance of writers and journalists and historians in capturing a very searing and traumatic event.”

Writers will struggle for years to come, Boog said, “but if we follow the example of the 1930s and stay in the streets and we keep mobilizing, raising our voices, asking for support, and making sure people recognize that writers and creative people are suffering during this time too and need help — once that happens, then maybe we can see some change.”

Kipen, for his part, has grand ambitions for a new FWP: It could “help reintroduce a divided country to itself,” lead to “greater social cohesion,” maybe introduce the next Cheever and Wright.

“But before the project hires a single writer or publishes a word, our goal will be to pass a bill that reassures Americans — writers and nonwriters alike — that their country values their stories,” Kipen said. “To paraphrase FDR, the first thing to hope for is hope itself. How’s that for grand?”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.