How California’s culture industry manufactured the California dream

- Share via

On the Shelf

California Mythmaking

Dream State

By Mick LaSalle

Heyday: 224 pages, $28

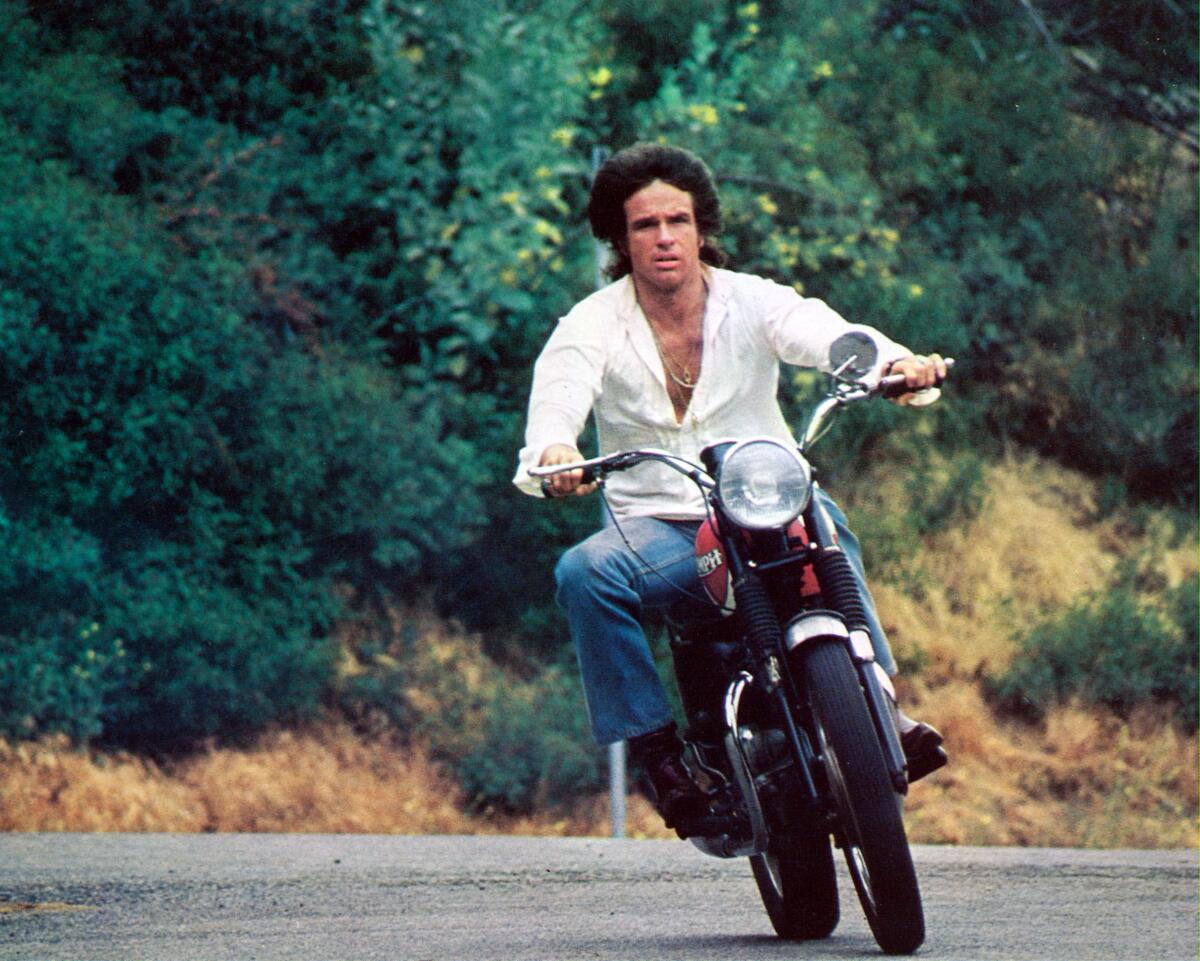

Hollywood Eden

By Joel Selvin

House of Anansi: 320 pages, $28

Rock Me on the Water

By Ronald Brownstein

Harper: 448 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Growing up in Berkeley, I was told nothing but bad things about Los Angeles. Superficial, smoggy, you know the drill. Then I got old enough to start hanging out in L.A. and quickly realized I had been lied to. This place was a million cities in one. Yet the myths I had been raised on continued to fascinate me — not just the nightmares (some of them quite real: fires, mudslides, serial killers, etc.), but the sweet dreams too.

Contrary to those who would split California in two, the north-south divide — cool intellectualism versus sunny flatness — is as much a myth as the dream of Manifest Destiny that preceded it: L.A. is now among the cultural capitals of the world, and San Francisco is its own kind of (very expensive) paradise. But all these myths are still worth studying, especially when you consider who made them, and thereby profited.

Three new books examine the mythology of the Golden State via its postwar 20th century proselytizers, the makers of pop culture. Mick LaSalle’s “Dream State: California in the Movies” is, as he writes, about both “the idea of California depicted in the movies” and “California ideas” that movies have seeded into the culture. Joel Selvin, the Berkeley-bred former pop music critic at the San Francisco Chronicle, casts his gaze southward to the Los Angeles of the late ’50s and ’60s for his new book “Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast Cars and the Myth of the California Paradise.” And in “Rock Me on the Water,” Atlantic senior editor Ronald Brownstein takes on the entire entertainment industry but focuses specifically on L.A. in 1974.

Readers thought Stephanie Danler’s debut novel, “Sweetbitter,” was autobiography. The reality, in her memoir “Stray,” is far more painfully dramatic.

If California seems to think a lot of itself, these books argue that it has many reasons to, from the weather to its youthfulness and its unself-conscious diversity. It wasn’t always so. “There was a time,” writes Selvin, “when California was a quiet corner of the country and Hollywood was a small town. Outside of the people who lived there, few Americans gave much thought to the sunshine and the beaches of the West Coast.”

As Selvin writes, a handful of young artists, including Jan and Dean, the Beach Boys and the Mamas and the Papas, were largely responsible for implanting the myth of Southern California in the national consciousness. “Good Vibrations” sounds like a forever future, as if a fleet of tanned aliens touched down to share their music. (In fact, it was just the genius of Brian Wilson and an army of session musicians.)

“Somehow in those records, those teenagers galvanized a growing sense of what California’s possibilities were,” Selvin says by phone from his San Francisco home. “Keep in mind, this is before commonplace jet travel, and a trip to California was very far away for most people.”

For a tale of dreams, however, there’s a lot of hustle going on in “Hollywood Eden.” One small record label squares off against another and another. Record producers, from top dogs (Lou Adler) to novelty kings (Kim Fowley), scour the scene for potentially profitable talent. For every sonic visionary, be it Wilson or Phil Spector, there are a dozen people scraping by.

Phil Spector was hospitalized after he became ill with COVID-19, said a source familiar with his medical condition.

Myths turn out be a commodity too — and a grind. They can turn dark in a hurry. Jan Berry, who rose to fame largely by singing about fast cars, wrecked his Corvette in 1966 and never fully recovered from his injuries, including brain damage. He was only 25. Spector was convicted of murder in 2003. One tale left out of Selvin’s book involves Beach Boy Dennis Wilson’s old roommate, Charles Manson. A frustrated, failed musician, he’s a major player in William McKeen’s 2017 book “Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los Angeles.”

What Selvin does so well is focus on a specific community and what made it work, starting with the 1958 class of West L.A.’s University High School (which included Jan Berry, Dean Torrence and Nancy Sinatra, who “drove herself to school every morning in the first pink ’57 Thunderbird”) and fanning out from there. Selvin took a similar approach in his ‘60s Bay Area pop book, “Summer of Love.” Here he zooms in tighter on less trodden ground, with more revelatory results.

In LaSalle’s “Dream State,” San Francisco is framed as blithe and indifferent to the concerns of mere mortals. Take “Vertigo,” in which Hitchcock puts Jimmy Stewart through the paces of a nervous breakdown. “Set in New York,” LaSalle writes, “it could not have been the same movie, because in New York everybody is having a nervous breakdown. But in San Francisco he’s all alone.” In the noir “D.O.A.,” Edmond O’Brien stumbles around Market Street after being poisoned. “San Francisco isn’t happy that O’Brien is going to drop dead in the next few hours,” LaSalle writes. “It’s just too beautiful to get worked up about it.”

LaSalle, the San Francisco Chronicle’s film critic, takes on both Californias, north and south, which gives him a lot of room to operate: film noir; disaster movies; even a hilarious chapter about “The Wizard of Oz” as the ultimate movie about Hollywood. As he writes, “Can you see why Hollywood might have been attracted to this story of a man who goes to a gorgeous place and becomes the biggest thing in town by conning everybody?”

LaSalle finds commonalities between the two Californias. “There’s a sense of possibility, a sense that you can change, you can have a better life,” LaSalle says in a phone interview. “But the poison part of the apple is that all these things are grounded in basically selfish values. So if you subscribe to the dream fully, then you end up never really being able to achieve it.” The dream becomes a pyramid scheme in which cynics rule and true believers lose out.

From the outside, meanwhile, California has it made. Hence the popularity of the disaster movie. “God will actually take that whole chunk of the country and plunge it into the ocean,” writes LaSalle. “And with that happy thought, frozen East Coasters get a warm feeling as they take their plastic scrapers and try to get the ice off the windshield.”

Hollywood loves to destroy Los Angeles — whether it’s earthquakes, floods, aliens, nuclear holocaust or climate change.

Brownstein, befitting an Atlantic editor (as well as a former longtime columnist for The Times), gets more political than either Selvin or LaSalle. “By the early 1970s,” he writes, “the music, movies, and television emanating from Los Angeles all reflected the demographic, social, and cultural realities of a changing America much more than the nation’s politics did.” He’s writing about the L.A. that produced “All in the Family” and “Mary Tyler Moore,” “Chinatown” and “Shampoo,” Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell, and an industry shift from East Coast to West. His book is more about what L.A. was pumping into the world than any geographic space. In other words, the myths. This Los Angeles was a crucial bastion in what we now know as the culture wars.

It was also still a small enough city to feel novel, even a little innocent. Anjelica Huston, who moved from New York to L.A. in 1973, recalls riding her horses through Griffith Park. The city “was like a big garden to me,” she says in the book; it “felt both incredibly glamorous and a little provincial.” It was a city still becoming itself, in many ways. For instance, Brownstein writes, “The Los Angeles Times was emerging from its insular, arch-conservative past to pursue its ambition of becoming a world-class newspaper.”

Huston’s garden couldn’t last. Drugs “cut through the music and film communities like wildfire,” Brownstein writes — and makes the familiar observation that “Jaws” spawned the summer blockbuster and doomed the auteur. The music business gravitated back toward New York and the television industry, “under pressure from the first stirrings of the religious right,” went on to create “the blandly nostalgic ‘Happy Days,’” which supplanted “All in the Family” as the top-rated show of 1976. Before long it was supplanted in turn by the myths of California’s own Ronald Reagan — “Dynasty,” “Dallas,” “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.”

There’s always some overlap between California and the myths it creates, some real-life inspiration for the stories and songs of fun and sun and disaster. No single book can wrap its head around the whole thing. Read a few, however, and you might arrive at something resembling a California state of mind, a vision of that which could never actually exist.

Eddie Van Halen, son of blue-collar immigrants, went to Pasadena High. David Lee Roth, his dad a doctor, attended Muir. Their meeting remade rock.

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.