Review: Helen Frankenthaler, underrated artist? A tantalizing but incomplete new bio of her rise

- Share via

On the Shelf

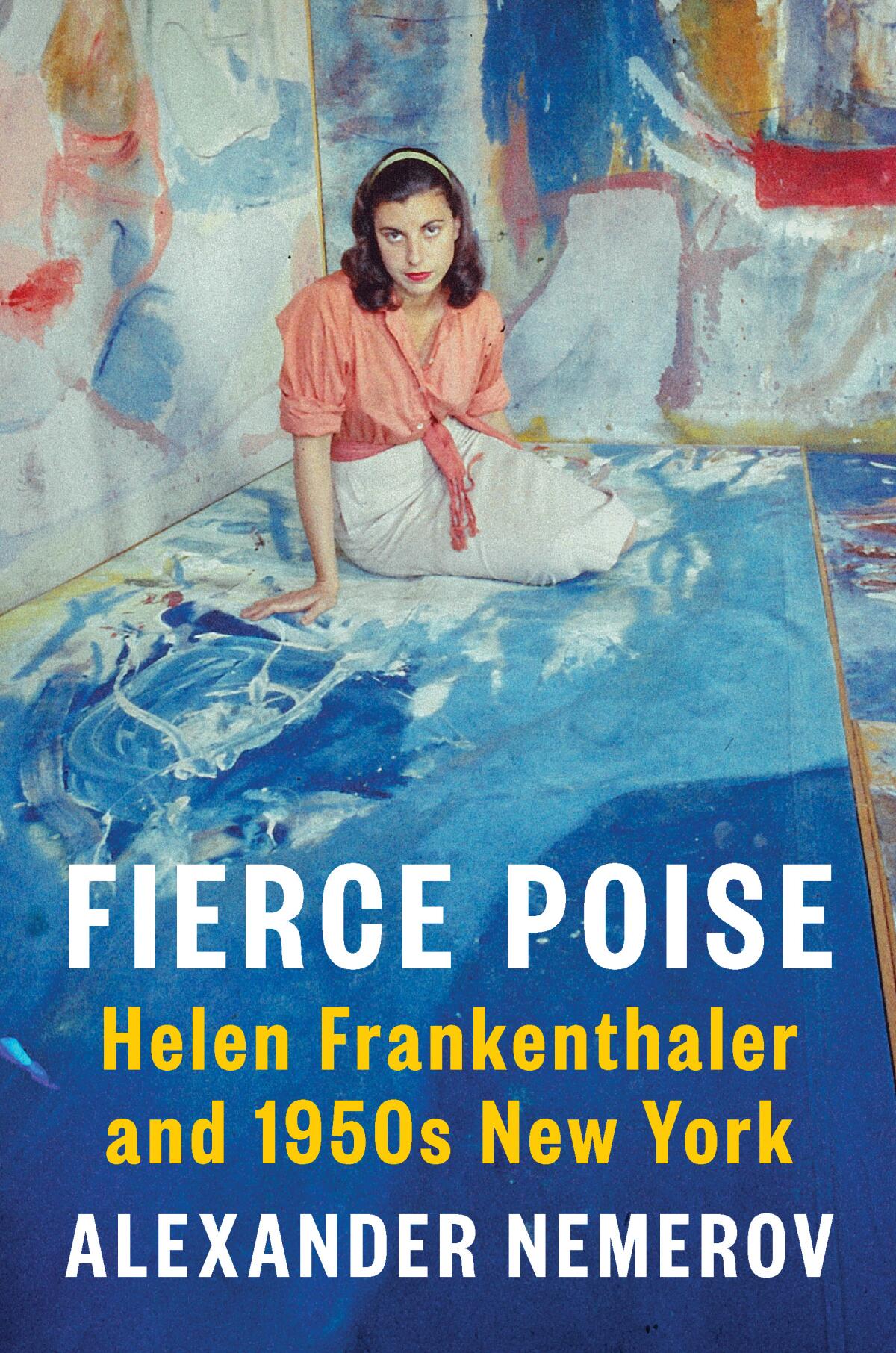

Fierce Poise: Helen Frankethaler and 1950s New York

By Alexander Nemerov

Penguin Press: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

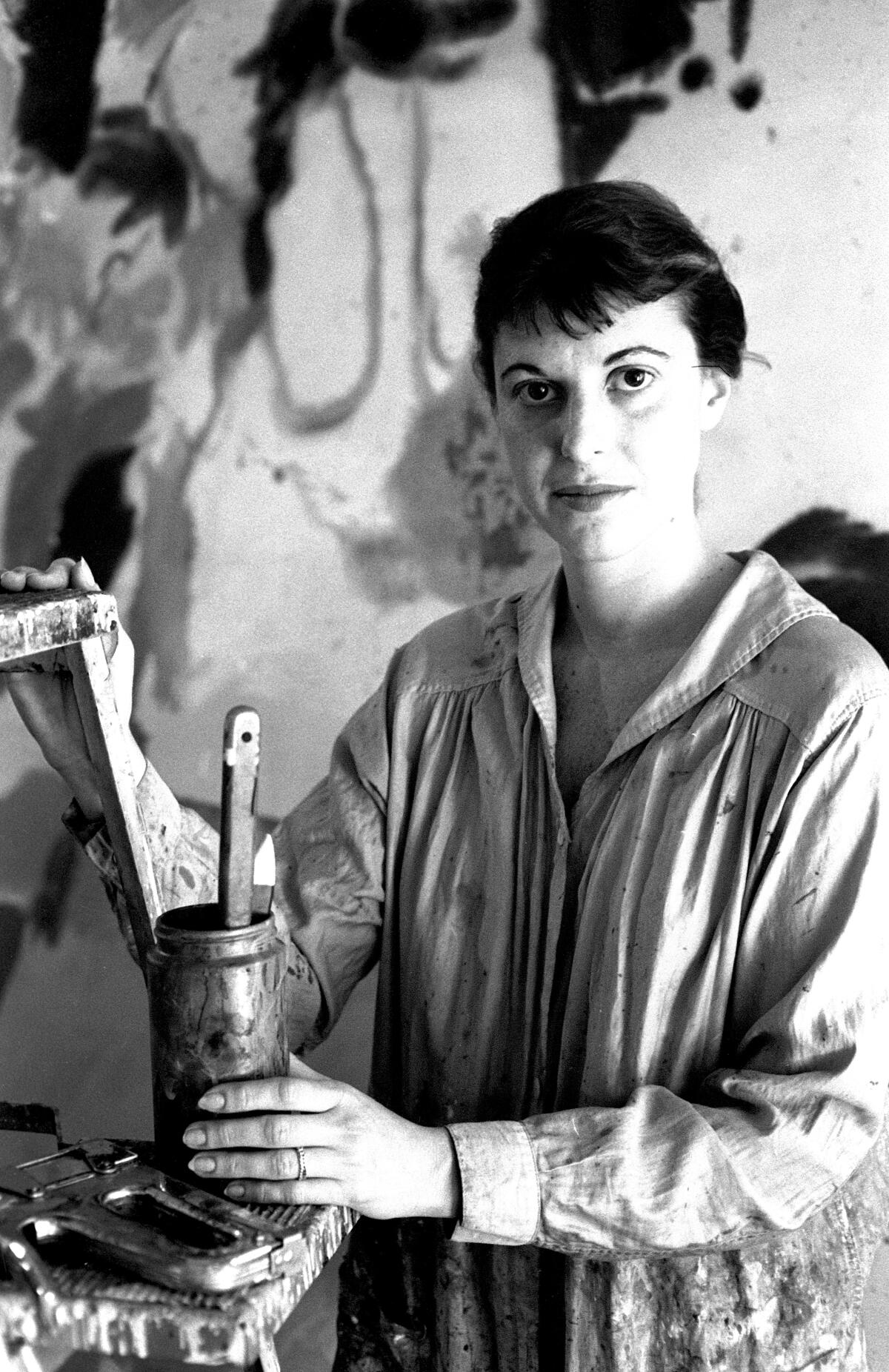

The cover of “Fierce Poise,” a new biography of the painter Helen Frankenthaler, features a famous photograph of the artist, shot by Gordon Parks, from a 1957 article in Life magazine on “Woman Artists in Ascendance.” Frankenthaler appears “pouty, confident, and serene,” writes Alexander Nemerov, her latest biographer. “She likely understood nearly as well as Parks how to craft an image exactly for the magazine’s massive target audience.”

Frankenthaler is also the cover girl for Mary Gabriel’s brilliant group biography of the women of Abstract Expressionism, 2018’s “Ninth Street Women” (soon to be adapted by Amy Sherman-Palladino for Amazon). Gifted with privilege and connections and unashamed to use them, Frankenthaler put her image to work and was criticized for it. “Easy for Helen to be the fairy princess,” the painter Grace Hartigan wrote in her journal in 1950. “She hasn’t seen the dragon yet.”

Nemerov knows a bit about pedigree. He is a professor, an author, a son of the poet Howard Nemerov and a nephew to photographer Diane Arbus. He nods to Frankenthaler’s privilege on Page 1: “A child of the Upper East Side, she was never an underdog. She had money, she had means, and she knew how to get ahead.” Her father was a New York State Supreme Court justice, her mother a scion of the upper class.

“Fierce Poise” focuses on the artist in an unconventional way: It covers the years 1950-60 in 11 chapters, each jumping off a specific date during one of those years. The resulting book is lively but short, skimming the surface of Frankenthaler’s work. Nemerov calls this choice “true to Helen” in that “the singularity of a day offers me an unscientific precision — a fluid glimpse into a moment — like Helen’s own.” The conceit is that the early days capture the essence of her work, but the constraint only shortchanges her contested legacy by eliding the rest of her long career.

“In the Land of the Cyclops” is the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s first essay collection in English, a refreshing shift from his epic, “My Struggle.”

Frankenthaler always seemed to know she would be a painter. “She started painting seriously at Dalton,” the tony private school, though her mother hoped she would eventually fall in line like her sisters, get married and produce children. Helen, possessed of an eerie “poise” from the start, apparently made up her mind that none of that was for her.

When she was asked to put together an exhibit of work by recent graduates of Bennington, her alma mater, she called up Clement Greenberg, perhaps the most powerful art critic of the 20th century, and invited him to come. Soon they were a couple. Frankenthaler was shamed by other artists for her relationship with “Clem.” “Her house was open to anyone who could help her career,” a friend said. “It was a single-minded pursuit.”

Early critics said her paintings looked like “a rag for wiping brushes.” Joan Mitchell called her “that Kotex painter,” referencing the smears in her work. People were, in a word, jealous, and they had a right to be, given her advantages. The thing about the green-eyed monster is that it feeds most ravenously on real talent. Frankenthaler had it. Her confidence in her work persisted in the early years, even after her separation from Greenberg, even after she failed to sell a single piece.

“In many ways this is a young person’s book,” Nemerov writes in his introduction. “It is about the person Helen was when she was young. It is inspired by my young students and what they believe and feel.” Youth is enticing but also limiting. Gestures toward acknowledging the difficulties in Frankenthaler’s career come across as merely that: gestures. When Frankenthaler went to Franco’s Spain in 1953 she did so, Nemerov explains almost defensively, “to look at art” as “politics was never her passion.”

Frankenthaler began showing her work in the immediate postwar period. In “Ninth Street Women,” Gordon writes that her trip to Europe in 1948 with her friend Gaby Rodgers was “a difficult trip not least because the quays where transatlantic ships docked in Europe were full of the coffins of American servicemen whose bodies were still being sent home three years after the end of the war.” Politics may not have been Frankenthaler’s “passion,” but the brutal facts of the war were certainly part of her experience and consciousness.

While guests of Provincetown’s Fine Arts Work Center are stuck through June, canceled residencies across the U.S. endanger an artistic ecosystem.

Nemerov touches on Frankenthaler’s Jewish identity through a concept of Greenberg’s that he called “Innerlichkeit,” or inwardness. Greenberg believed that even in the aftermath of the Holocaust, it was the Jewish artist’s responsibility to “emancipate himself from the world, to find [a] home in his Innerlichkeit without display, without making his emotion either a commodity or the motive of a Quixotic politics.”

The notion arises in the context of Frankenthaler’s painting “Mountains and Sea” — which features, Nemerov writes, “disarmingly private shapes and stains on a canvas of the size previously reserved for grand public statements, the coronation of kings, the storming of fortresses. It was as if one of the history painters of the nineteenth century had depicted, on a vast canvas, not the surrender of a city, not the decadence of the Romans, but a personal thought, a private emotion.” These are fascinating concepts, and a biography with the space to consider their relevance to the social and political moment would help Frankenthaler’s achievement to resonate more clearly.

Moments like these make the reader pine for more, especially on Frankenthaler’s later career, when her dual talents for painting and promotion merged to solidify her status as a giant of Abstract Expressionism even as her privilege and gender prevented her from being taken seriously. There is more than a whiff of internalized sexism here, as if her success was unwarranted. She told the art critic Deborah Solomon in 1989, “My life is square and bourgeois.” Nemerov too seems to suffer from self-doubt, believing he isn’t qualified to write a full biography of Frankenthaler, but “Fierce Poise” proves otherwise.

The book ends with a “Coda,” the reader a ghostly witness to Frankenthaler’s coming into her celebrity in 1969 with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum. Nemerov describes the artist’s “radiance” in this moment, but without context the conclusion rings a bit hollow. We are missing what it was truly like for Frankenthaler to be “the artist alone before her picture,” standing in front of those epic canvases, fatigued but thrilled, looking in. Perhaps a sequel is in order.

Heather Clark fuses new discoveries and eye-opening analysis in an inspiring biography, “Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath.”

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.