Review: The painful, joyous origin story of an L.A. Koreatown family, unfurled in a warm debut

- Share via

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Every immigrant group in the United States has settled in enclaves. Some have faded, like Manhattan’s Yorkville, now just a handful of German bakeries and butcher shops on the Upper East Side. Others, like San Francisco’s Chinatown, developed a kitschy veneer, their survival rooted in tourism.

“The Last Story of Mina Lee,” a debut novel by Nancy Jooyoun Kim, locates itself in the still-thriving enclave of Los Angeles’ Koreatown. We see it first from the perspective of Margot Lee, a Seattleite in her late 20s, who hitches a ride with her friend Miguel to L.A., knowing she’s overdue for a visit with her mother, Mina. On arrival, they find Mina Lee dead on her apartment floor.

Cleaning out Mina’s meager possessions, Margot makes a few surprising discoveries, including some travel brochures for national parks. “It’s some kind of Korean immigrant rite of passage,” she tells Miguel. “National parks, reasons to wear hats and khaki, stuff like that. It’s like America America.” While chuckling at strivers like her mother, Margot envies her white friends, “people who seemed to navigate their identities, their skin tones, their appearances so easily, in such an invisible way, as if the world had been created for them, which, in a sense, it had.”

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

As Margot digs into Mina’s past, her own immigrant double consciousness takes a back seat to her mother’s history — her life in Korea and passage to the U.S. in search of a self-made future. Kim has spoken in an interview about the urge to fashion a Great American Immigrant Novel of sorts: “I wanted to write a story that I had never seen before, a story that explored the complicated interdependence between an immigrant mother and her American-born daughter, the ways in which they love, need and sometimes resent each other.”

The novel’s interior moments — in which mother and daughter think tragically past each other — work best. “Her mother didn’t have time for empathy. She always had to keep moving. If she stopped, she might drown,” thinks Margot. Mina’s actual feelings complicate that picture: “Had she known that would be their final moment together. ... She would’ve confessed that she was terrified of everything her daughter did, things breaking, objects in disarray, because she could not afford to lose another thing that she loved in her life.”

Had the author kept the narrative this close, “The Last Story of Mina Lee” would have been a stronger book, its tangled subplots (Korean flashbacks, organized-crime figures) more of a counterbalance to the characters’ yearnings. Unfortunately, Kim succumbs to a common failing of first novels, telling too much. We hear again and again about the lack of agency in Mina’s life, Margot’s erasure and misunderstanding of her mother’s world, Mina’s insistence that women “lack shape” without men, and so on.

It’s a shame, because as Margot learns more about her mother’s generation, Kim’s characters and settings show plenty. Mina, whose first husband and daughter (Margot’s half-sister) were killed in an accident, came to California swept up in grief, taking a room in an “ahjumma’s” (auntie’s) house and a job stocking vegetables in a supermarket. There she met a man named Chang-hee Kim and embarked on a sweet and funny courtship.

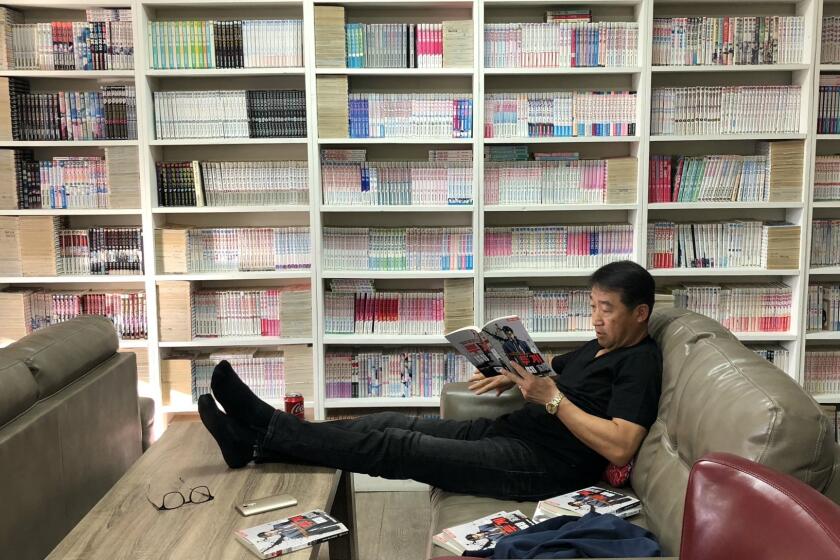

In honor of the Winter Olympics taking place now in Pyeongchang, I visited Koreatown’s bookstores.

At the ahjumma’s house, Mina also met Mrs. Baek, who enticed the new arrival out of her room and her depression with delicious meals. Doenjang jjigae, kkakdugi, gosari namul, maeuntang: The author translates some of them, but leaves many as they are — a sharp choice that telegraphs comfort and familiarity. As Margot’s inquiries into her mother’s past overlap with Mrs. Baek’s present, she realizes just how few choices immigrants have, especially women. Here again, Kim attains the right show-tell balance, leaving connections for readers to make.

Margot wants more from her mother’s story, a need that drives her to learn some things others wish she didn’t know. Less chatter about Margot’s needs might have opened up more space for us to see that all stories dig into tender places. “Maybe that’s what she had been doing this entire time — hardening herself for the truth,” Mina thinks, in an over-explained passage. “Some questions were never meant to be answered, yet ideally, pursuing them might at least shed light on how much you valued yourself, the need you might have to tell your own story, however fragmented it might be. It was okay to yearn for the impossible every now and then as long as in the yearning you discovered something about yourself.”

All of that is Fiction 101. And yet it also feels true: Immigrants often do have a hard time articulating themselves plainly across generations, feeling trapped in the crosscurrents of expectations. “The Last Story of Mina Lee” may not be perfect, but it’s a story that cries out to be told.

Mi-Ae Seo’s chilling homage to ‘Silence of the Lambs’ joins a burgeoning genre.

The Last Story of Mina Lee

Nancy Jooyoun Kim

Park Row: 384 pages, $28

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.