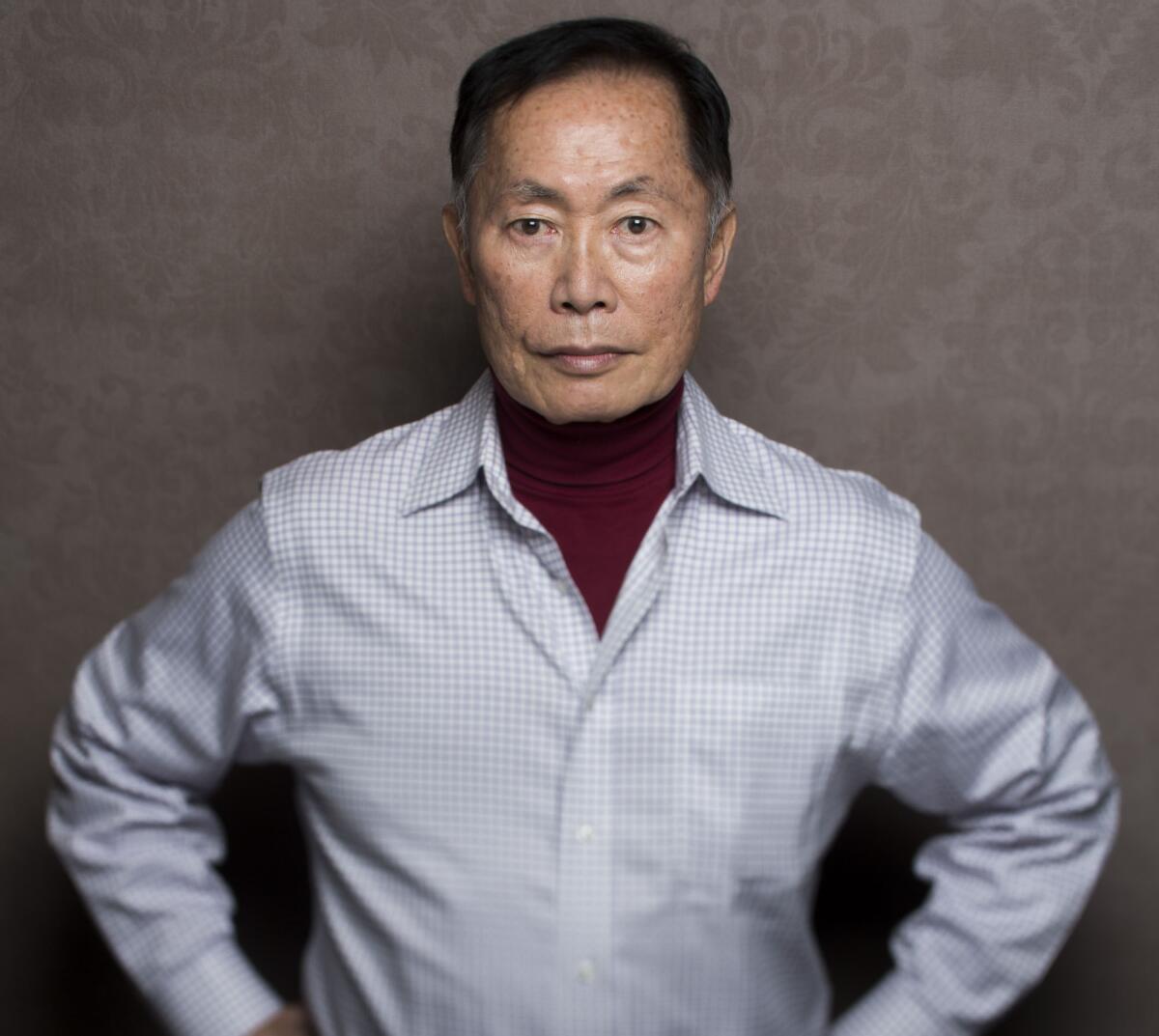

Review: George Takei’s ‘They Called Us Enemy’ shows injustice through a child’s eyes

- Share via

In today’s America, we’ve seen the television images of migrant children in cages so many times that it’s all too easy to develop compassion fatigue. After all, we can turn off the set without actually being compelled to contemplate the plight of being imprisoned at a tender age in a strange, harsh place, at the mercy of forces that we don’t really understand.

But former “Star Trek” actor George Takei, who as a child was one of 120,000 Japanese Americans rounded up from their homes by U.S. authorities and sent to internment camps during World War II, knows all too well how that feels. He seems determined to jolt the rest of us out of our apathy and make us understand.

In “They Called Us Enemy,” his graphic memoir, Takei has found a powerful way to deliver his message. The book ingeniously uses a medium that most of us first experienced as children — comic book-style drawings, dialogue balloons and sparse, simple narration — to help readers see it all through the eyes of the child he once was.

The story begins abruptly, with 5-year-old George and younger brother Henry being awakened one morning by their father, an immigrant who built a successful dry-cleaning business. His dad frantically hurried to dress the boys as he pleaded with the soldiers standing in the doorway of the family’s Los Angeles home for a little more time.

Takei’s mother clutched his baby sister as the family was forced to board a bus that took them to the Santa Anita racetrack, where they were quartered in stables reeking of horse manure. But before long, soldiers herded them and other Japanese American families onto a train, for the long ride to the Rohwer Relocation Center in eastern Arkansas, where they dwelled in wooden barracks surrounded by barbed-wire fences, under the scrutiny of riflemen in a watchtower.

Takei recounts that they endured stifling heat and rainstorms that turned the camp into a sea of mud. They ate unfamiliar, bad-tasting food, relieved themselves in rows of toilets without stalls, and built their furniture from scraps of discarded wood.

With “They Called Us Enemy,” George Takei details childhood years in Japanese Americans internment camps.

He digs deep into his memory to vividly re-create what it was like to be a young boy growing up in captivity, from the adolescent neighbors who slyly tricked him into uttering curse words to the guards, to the camp Christmas party at which he discovered, to his shock, that the Santa Claus wasn’t the usual roly-poly Caucasian from department stores but rather a Japanese American imposter with a padded midsection to make him seem more jolly. (He decided to keep that secret from the other children, for fear of disappointing them.)

The book shifts back and forth between that naive perspective and the more complicated and painful narrative of his formerly middle-class parents’ struggle to cope with the humiliation of having their property and savings taken from them, and their basic rights and dignity stripped away. Takei’s father dealt with his own despair by doing what he could to help new arrivals, and his businessman’s acumen and calm demeanor led his fellow internees to appoint him as the manager who negotiated with guards on their behalf. His mother proved just as resilient and resourceful, smuggling a forbidden sewing machine into the camp in her suitcase so she could make clothes for her three children.

But when their captors insisted that they sign a loyalty pledge and forswear allegiance to the Japanese emperor, Takei’s parents refused. That earned them a distinction as “No-Nos.” It wasn’t just defiance, Takei explains. Saying that they no longer were loyal to Japan seemed like an admission that they were enemy aliens and not true Americans — a particularly bitter pill for Takei’s mother, who had been born in the U.S. As a result, in 1944, the family was shipped back to California and confined at Camp Tule Lake, a high-security facility for Japanese Americans who were deemed to be dangerously disloyal.

There, as Takei recalls, the strain of captivity caused divisions within the captive Japanese Americans. Some rejected the America that had wronged them. They defiantly marched around the camp, chanting angry slogans in Japanese, and quarreled with non-resisters.

The book later describes Takei’s impassioned adolescent debate with his father, who tries to persuade him that President Franklin Roosevelt, who authorized their captivity, was a fundamentally good man who had made one terrible mistake.

As “They Called Us Enemy” details, Takei eventually transcended his youthful anger and emulated his father’s wisdom and compassion, even as he leveraged his television stardom to campaign for official recognition of the wrong that had been inflicted on Japanese Americans.

He draws a discomforting parallel between the indignities he and his family suffered and the current treatment of asylum seekers from Syria and Central America.

“Old outrages have begun to resurface,” he warns. Takei’s ability to make that connection to his own experience makes his memoir even more powerful, moving and relevant.

They Called Us Enemy

George Takei with Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott; illustrated by Harmony Becker

Top Shelf Productions: 204 pp; $19.99

Book Club: If You Go

The Los Angeles Times Book Club welcomes George Takei in conversation with Times reporter Teresa Watanabe.

When: 7:30 p.m. Sept. 10

Where: The Montalbán Theatre, 1615 Vine St., Los Angeles.

Ticket info: latimes.com/bookclub

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.