- Share via

Let us return to the halcyon days of July, when a clever, contagious portmanteau seemed to sum up the entire movie season. Barbenheimer was everywhere, the answer to all box office woes, a something-for-everyone double feature boasting a pair of movies we were told had little in common. Indeed, that was supposed to be part of their appeal. “Oppenheimer” was the epic, deadly earnest biopic of the reluctant father of the atomic age. “Barbie” was the pastel, postmodern feminist frolic, a deceptively substantial paean to product placement and invitation to in-theater cosplay.

What we didn’t hear about as much: These two blockbusters are basically about the same thing, even if they take drastically disparate paths to make their points. The memesters, bless their hearts, got it almost immediately. A popular example features the words uttered by J. Robert Oppenheimer in the film, cribbed from the Bhagavad Gita, rendered in bouncy pink-and-white text: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Yes, this is the central theme of both “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer.” As Sufjan Stevens sang in his song “Fourth of July,” a gorgeous little slice of sad resignation, “We’re all gonna die.”

But “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie” aren’t just about death. They’re about the terror that the inevitability of death inspires and the anxiety that accompanies the knowledge of our mortality. They work on different size canvases and with much different stakes. Yet they’re both shot through with a quality not normally associated with tentpole movies. Who knew existential dread could be so profitable? The two movies have combined for more than $2 billion in global box office.

“Barbie” serves its fear and trembling with a Day-Glo nod and wink, which somehow makes it even more pungent. Boogieing her heart out at her own raging dance party, Barbie (Margot Robbie) pauses to marvel at how awesome everything is: “It is the best day ever. And so is yesterday, and so is tomorrow.” And then, without removing the smile from her face: “Do you guys ever think about dying?” Uh-oh. Trouble in paradise. She claims to be all better by the time she lays her head on her pillow that night — “Goodnight, Barbies! I’m definitely not thinking about death anymore” — but it’s too late. Pandora’s box has been opened.

As it turns out, Barbie’s mortal thoughts are just a symptom of being human, or at least approaching humanity. Out in the real world, a Mattel employee (America Ferrera), facing her own life crisis, is hatching ideas for new Barbies, including Irrepressible Thoughts of Death Barbie and Crippling Shame Barbie. This helps explain why, back in Barbie Land, our heroine is experiencing symptoms of imperfection, from flat feet to bad breath. It seems there is a tear between the fantasy and real worlds, and the only way Barbie can mend it is by visiting us plebes over here in the rat race.

In “Barbie,” the defining trait of being human is the knowledge that we will all decay and end up as worm food. Once the original panic wears off, this knowledge isn’t such a bad thing. The first time I saw the movie, I overheard a guy at the theater exit: “That was way more existential than I expected.” Indeed. “Barbie” was the year’s greatest Trojan horse, a pop art tale of empowerment that wants us to think about what it means to shuffle off this mortal coil.

“Oppenheimer” goes well beyond fear of one’s own death to ask a question few have ever had to ponder: What does it mean to help create technology capable of wiping out the entire human race? To toil for the sake of ending a catastrophic war, only to see your work adapted for purposes potentially more lethal than anything previously known to man? To become, in a sense, a destroyer of worlds?

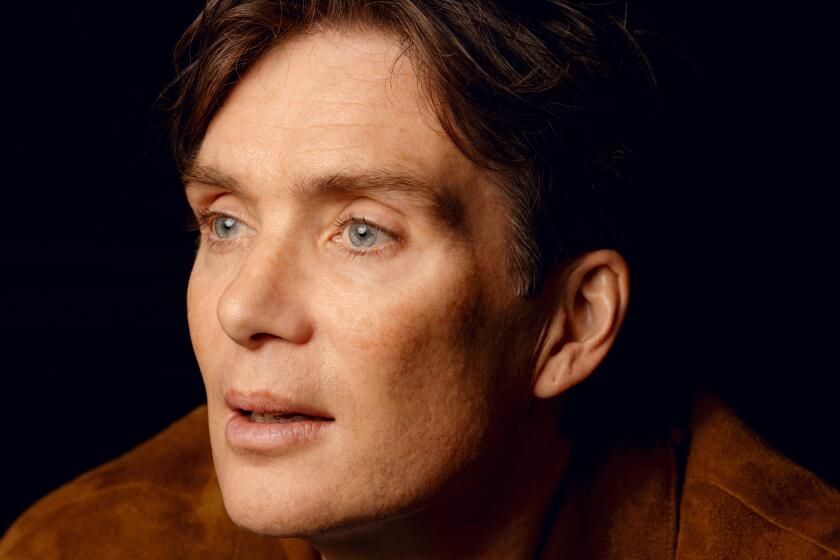

The stakes here aren’t just death; they’re the possibility of extinction. Or, as Cillian Murphy’s J. Robert Oppenheimer argues in support of using atomic weapons against Japan, “The atomic bomb will be a terrible revelation of divine power.” Then, in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as he addresses a zealously cheering crowd at Los Alamos, he is visited by his own subjective sensations of death. Agonized screams. A charred body on the ground, which he steps through, a horrified look on his face. “Oppenheimer” is a tale of what we hath wrought, filtered through the experience of a man whose pallid complexion and tormented insularity make him look like an envoy from the Grim Reaper himself.

The actor and director Christopher Nolan share a mutual interest in conveying a character’s emotional conflict through close-ups that linger on an actor’s face and allow the audience to feel inner turmoil.

If Oppenheimer had reservations about the atomic bomb, he was driven to despair over the prospect of the hydrogen bomb, or, as it was called then, the Super. This was an exponentially more powerful and deadly weapon, the next logical (or illogical) step toward mass destruction. Already reeling from his role in the Manhattan Project — “I feel that I have blood on my hands,” he tells a dismissive President Truman (Gary Oldman) — he became a fervent proponent of arms control and an opponent of what his friend and colleague Isidor Rabi (David Krumholtz) calls “a weapon of mass genocide.” As dramatized in the film, Oppenheimer paid the price for his anti-Super stance, losing his security clearance as the country he helped win World War II for made him a pariah.

“Barbie“ is interested in fear of death as a concept, providing a softer landing than the very concrete potential for extinction in “Oppenheimer.” Obviously, there are bigger differences as well. One is a pink dress, the other, a pork pie hat (“Oppenheimer” screenings would certainly be enlivened by a little cosplay). But both movies want you to remember that we won’t be around forever and that it’s OK if this reality raises anxiety levels. Yes, Barbie, we do in fact think about dying.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.