‘The Mission’ chronicles how a young missionary’s adventure -- or folly -- turned fatal

- Share via

Gripped by youthful, evangelical zeal and a thirst for adventure, 26-year-old American missionary John Chau was killed in 2018 while attempting to make contact with the people of North Sentinel Island, an Indigenous population living in an exclusion zone in the Indian Ocean. Chau’s driving intent to share the Christian Gospel with this remote tribe, sequestered from the rest of the world for thousands of years, was met with fatal arrows.

In “The Mission,” filmmakers Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss unpack the meaning of Chau’s journey — the focus of his decade-long obsession — and his life, which they reassemble through interviews, as well as Chau’s letters, social media posts and journal. Through multiple perspectives, the film casts Chau’s story in the broader context of colonial adventurism, and the cultural sway of what Moss calls “fantasy projections of the Western conception of Indigenous culture,” not exempting National Geographic, which produced it, or the explorer fictions that captivated Chau as a child, like “Robinson Crusoe” and the Belgian comic “The Adventures of Tintin.”

Although the filmmakers thoughtfully chronicled episodes of faith and crisis in “The Overnighters” (2014) and adolescent masculinity in “Boys State” (2020), Chau’s tragic story exerted a pull stronger than those themes alone.

Christian missionary John Chau was murdered while attempting to bring his religious beliefs to an unwelcoming island. A documentary explores what went wrong.

Questions abounded. “One was just understanding John’s path to North Sentinel,” said Moss, sharing a recent Zoom conversation with McBaine. “What was the world he came out of? Why would he risk his life to do something like this, that seems foolhardy, if not suicidal … was suicidal? The second component here was the Sentinelese. This island that is like the last unmapped place on Earth; what is the mystery that people have gone there seeking to answer for themselves?”

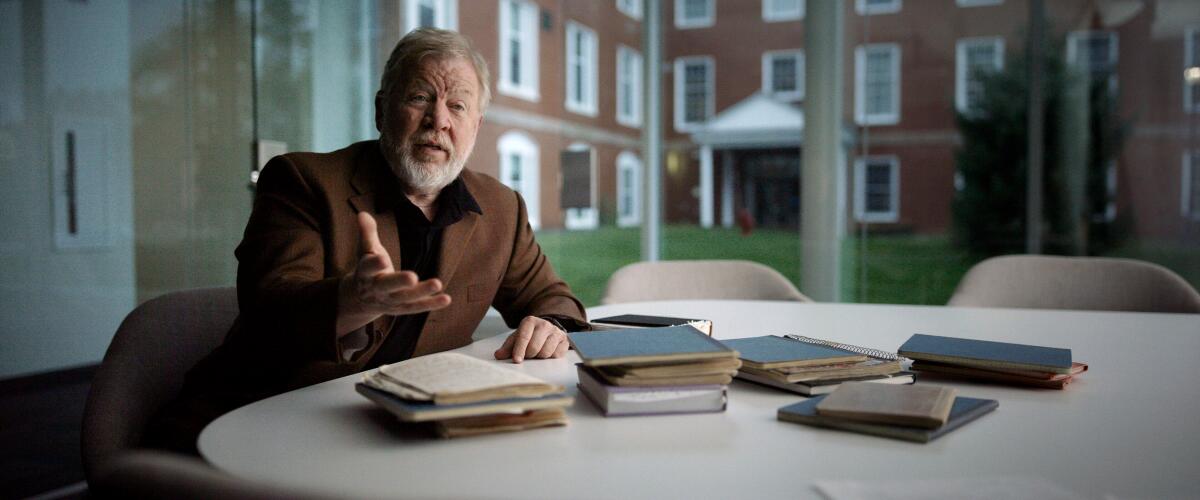

The film looks for answers from a variety of sources, including Daniel Everett, a linguist and former missionary whose experience with the Pirahã people of the Amazon rainforest led him to abandon his faith, and Adam Goodheart, whose book “The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance, and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth” recounts the history of North Sentinel Island. A nuanced dialogue develops, with the testimony of Chau’s friends, many of whom shared his faith if not his compulsion, and his father, a religious man who nonetheless discouraged his son’s more extreme ambitions.

“There’s this gulf, right, that exists between people of faith and secular communities,” McBaine said. “I’m just wondering if there’s a space for conversation there … also knowing that so much of the headlines covering this story felt a little reductive. You always want to know more, contextualize more.”

Moss and McBaine relied on animation to visualize passages from Chau’s diary as well as other key elements, including a letter to the filmmakers from Chau’s father, who declined to appear in the film (his words are read by an actor). Working with animation director Jason Carpenter (“He Named Me Malala”), the pair also found a way to explore Chau’s own enchantment with storytelling. “The conception that John willed himself into being the hero of his own narrative gave us a kind of freedom to think about the story form,” said Moss, who references a 1970s Christian comic book called “Through Gates of Splendor,” adapted from a book about missionaries in Ecuador in the 1950s. “There was a dreaminess to that imagery, which clearly captivated so many people. We felt that gave us permission to visualize this missing piece of the story in a way that was motivated by John’s own story language.”

Everett, who put his own family at risk when he went to the Amazon at age 26, sees Chau becoming part of the same dangerous myth-making as he is elevated to martyrdom. “I think what he did was fairly stupid, but I thought he was courageous. When I was his age, I would have thought very similarly,” he said. “It’s very unfortunate that that type of mythology can so capture someone’s mind that it leads them to these remote parts of the world, to people who don’t actually want them around at all, and to their death or the death of the people they’ve gone to.”

In the film, Goodheart evokes the story of Odysseus and the sirens to describe the allure. “The island and its people have taken hold of people’s imaginations in powerful ways … they signify something bigger,” Moss said. “The island represents on some level our pre-modern selves. These are people that live seemingly in a greater amount of equilibrium with their natural world. They’ve managed to for thousands of years. We can’t, so we’re suddenly much more aware of what we’ve lost.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.