Two big-eyed film stars who didn’t get the credit they deserve

- Share via

Their eyes are big, disproportionately so to the size of their head. They always seem to be drinking in the life around them, a little melancholy, seemingly rolling those eyes at the human folly they witness. Known for stubbornness, they actually exude nobility.

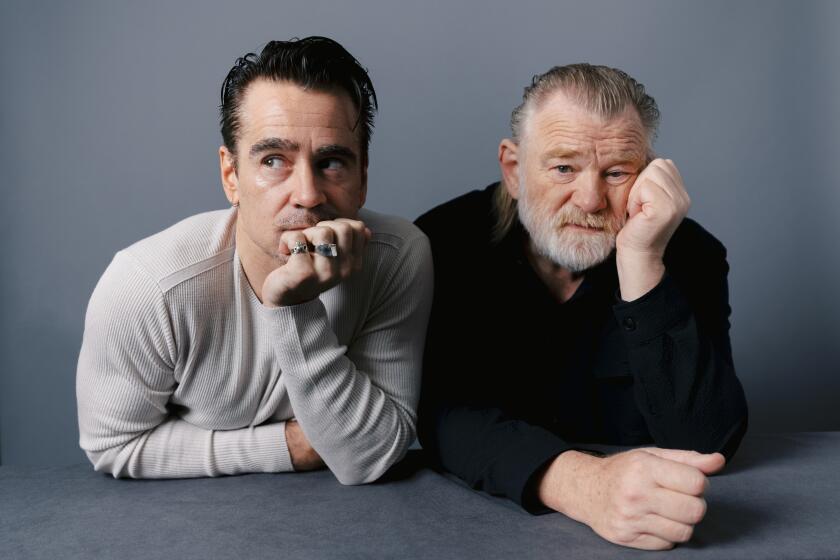

No donkeys were nominated when the Oscar finalists were announced in January, a sad but inevitable oversight. But they’re front and center in two of the year’s best films. “The Banshees of Inisherin” scored nine nominations, including four for actors Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, Kerry Condon and Barry Keoghan. But the scene stealer is a miniature donkey named Jenny, the beloved companion of Farrell’s lonely, tortured Pádraic and a key (if inadvertent) player in his ongoing drama with Gleeson’s Colm. Jenny might be the only sane character in the film.

The actors, good friends in real life, disagree about how best to live life and what leaving a legacy really means.

But she might have to take a back seat to the title character of “EO.” Nominated for international feature film, “EO” follows its hero from Poland to Italy, a route laden with fools, sadists, romantics and opportunists, a gallery of deeply flawed humans as seen through the eyes of a four-legged superior being. “EO,” like Robert Bresson’s transcendental 1966 masterpiece “Au Hasard Balthazar,” uses a donkey’s travels to highlight how screwed up people can be.

“Banshees” plots a similar course but on a smaller scale. “Jenny plays the role of the innocent observer through whom the whole story, of human foibles and ego, is quietly seen,” writer-director Martin McDonagh said via email. “In Pádraic’s life, she’s as much of a gentle, thoughtful pet as anything else, non-judgmental and kind. But for the story, she’s important because it’s through her gentle eyes that this never-ending human catastrophe is seen, and framed, as pointless and empty.”

In the Beckett-like absurdism of “Banshees,” Jenny is a rock of stability, especially for Pádraic, whose best friend, Colm, has decided he no longer likes Pádraic and is willing to commit grotesque self-harm to prove his point. Talk about stubbornness. Pádraic can’t really count on anyone — not Colm, not his sister (Condon), who longs to move away from their isolated Irish island home, and not Dominic (Keoghan), a nice enough kid but a bit of a village idiot. Much like Shrek, his only constant is his donkey pal. God forbid anything happens to Jenny.

If “Banshees” shows how a noble ass can stand out from her crazed background, “EO” pushes its furry friend front and center. The Polish film, directed by Jerzy Skolimowski (who wrote the screenplay with his wife, Ewa Piaskowska), is a full-on travelogue, following a Sardinian donkey across Europe, from the hands of people who love him to the clutches of those who want to turn him into salami.

Skolimowski commits fully to his lead character, filming much of “EO” from his point of view and looking deep into his eyes at every opportunity. (EO is actually played by six different donkeys, all bearing the Sardinian’s trademark of contrasting light gray and thick black hair, the latter going from the top of the head down to the tail and then crossing along the front legs. The coloring creates a sort of cross shape on the donkey’s back — in this case, a cross to bear.)

Skolimowski, 84, remembers how deeply “Au Hasard Balthazar” affected him the first time he saw it. Usually an analytical film viewer, he found himself weeping as Balthazar faces his impending death, surrounded by sheep on a hill. “Bresson taught me that an animal character can move you, perhaps even stronger than any human character portraying some incredible drama,” Skolimowski said in a recent video interview. “Our main task was to reach the audience with the message that animals are living creatures. Don’t treat them like objects. They have similar emotions to people. They also need the feeling of security, of care, of love. That was the main task of our film, to change the attitude of people towards animals.”

The filmmakers knew they wanted to make a film with an animal protagonist. The story of how they came to their donkey has a cinematic quality itself.

A few winters ago Skolimowski and Piaskowska found themselves at a Nativity show near Sicily. Near the end of the show visitors entered a barn, where they were met with geese, pigs, goats, sheep and other beasts — “It was like the whole zoo suddenly squeezed into one barn,” Skolimowski recalled. Suddenly, a chicken broke loose and flew across the barn, nearly hitting the actor playing Joseph in the head. The chicken landed in a shadowy corner of the barn, next to an animal that seemed to be hiding.

“So I approached that animal, and that was the first time in my life that I stood face to face with a donkey,” the director said. “The very first impression was his enormous eyes. They were huge and with a very specific melancholic look, like being present, but at the same time being deeply inside his thoughts. The eyes were not really observing. They were reflecting, or just witnessing what was going on.”

Yes, donkey love can run deep. But sometimes the appeal is quite simple. “They’re so bloody cute!” says McDonagh, who has created his share of bloody mayhem onscreen. “But they’re also smart, and loyal, yet also independent and in charge of themselves, like a cat perhaps, just with more empathy, seemingly. And they’re somehow old before their time. Jenny was only 2½, but it felt like she’d lived a whole lifetime. In my head she had, anyway.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.