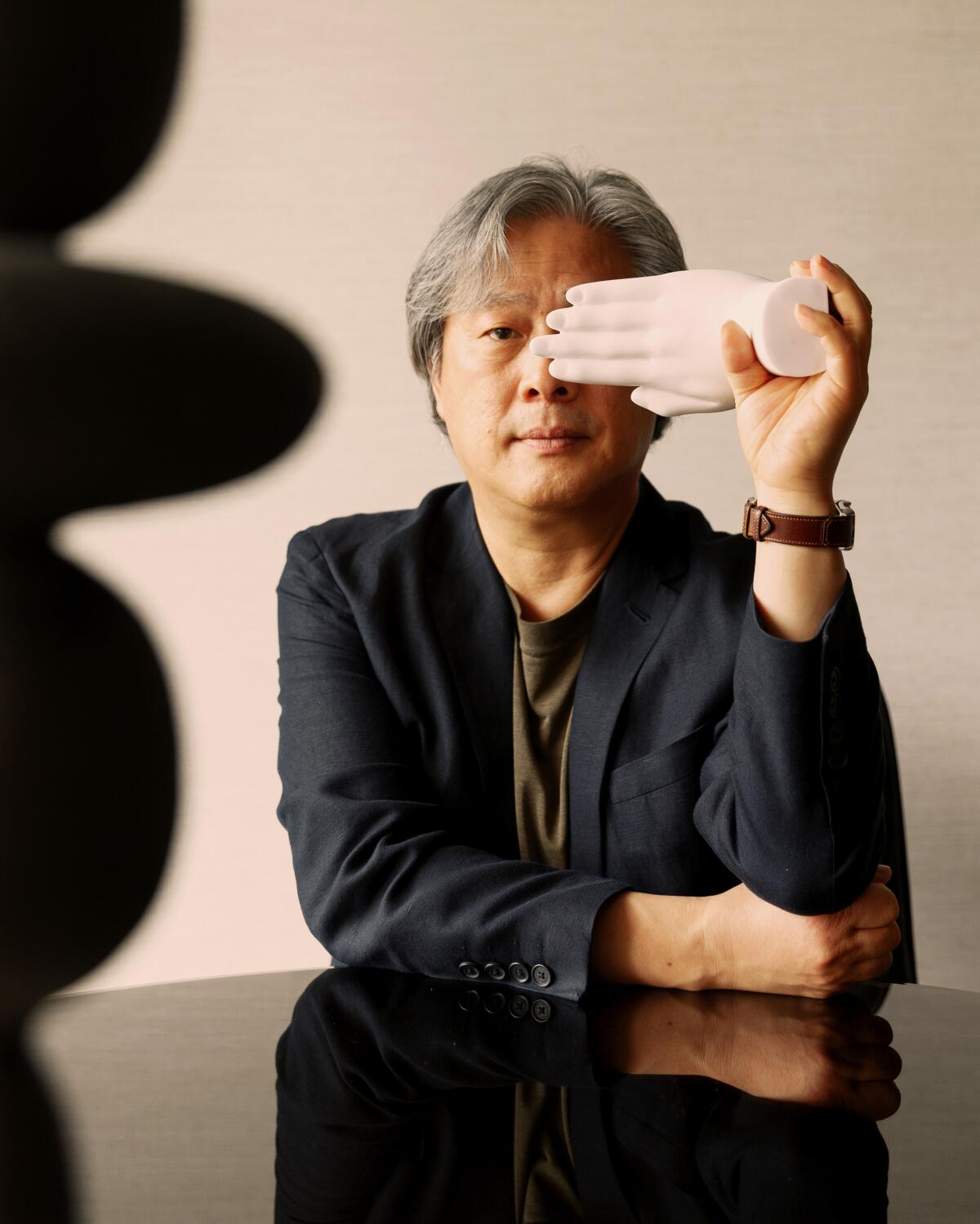

Why Park Chan-wook crafted ‘Decision to Leave’ so love is more mysterious than murder

- Share via

A detective falls for a beautiful murder suspect. But that’s just the beginning of the experience of “Decision to Leave.” In the hands of South Korean master Park Chan-wook (“Oldboy,” “The Handmaiden”), that familiar noir premise is just the outermost layer of a cinematic onion — a sweet one nevertheless containing sulfur. Deploying the tools of filmmaking with a surgeon’s precision and a sculptor’s talent for discovery, Park reveals that the movie’s most arresting enigma doesn’t concern murder, but love.

In the second half of his bifurcated film, “the investigation no longer matters. The biggest mystery is, ‘Why is she here in this town that has nothing to see but mist? Why did she come where [the detective] lives?’ That is how it transforms into a romance film,” the director says.

Indeed, the most prominent questions — still tied to a murder mystery — become not only whether she loves him, but whether he loves her.

“What’s interesting about this is he himself does not know the answer,” Park says, that is until a revelation in the most haunting final sequence in a film this year.

Our BuzzMeter film experts predict the Oscar winners in 10 categories. Check out the consensus picks, close races and interesting narratives - and vote in the polls for every category.

If a film defined by genre elements (for a while) seems surprising for a filmmaker as idiosyncratic as Park, it actually has been a long time coming. As a high schooler, he became a fan of the Swedish Martin Beck detective novels — the source of the American film “The Laughing Policeman,” starring Walter Matthau — so he’d been interested in making a detective thriller for decades. When the entire book series was translated into Korean a few years ago, he reread them to get to know the character “from his very start,” he says through an interpreter.

“I grew an interest in a detective character who does not rely on violence, but instead our focus is on procedure. He’s polite and he’s kind. He’s a civil servant.”

Meanwhile, a classic 1967 Korean song, the tantalizing “Mist,” inspired him to “make a mature romance film. At a certain point, I thought, ‘What if I combine these two separate ideas? What if Martin Beck falls in love with his suspect?’”

Park decided to make a film that would have all the trappings of a noir, a complete story, in its first half — then take viewers beyond, unmoored, into a second half where the mystery moves past solving a crime and into obsessive, irresistible attraction.

“If the story ended on Part 1, then you could call this film [nothing more than] a noir. Not to say it would’ve turned out worse that way. But even so, if the story ended at Part 1, I don’t think I would’ve made this movie,” he says.

Combining the genres wouldn’t work, of course, without compelling performances, and Park gets them out of Park Hae-il (whom he has called his country’s Jimmy Stewart) as a detective of no small renown and Tang Wei (unforgettable in Ang Lee’s “Lust, Caution”) as the beguiling Chinese-national murder suspect Seo-rae. But don’t look for the eruptions of sex and violence from beneath gorgeously controlled surfaces that have marked some of Park’s best-known works; compared to those, “Decision to Leave” is downright chaste.

“The goal was to make a love story that does not say the words, ‘I love you.’ I wanted to make the audience feel more curious and impatient about their relationship,” he says.

Park and frequent co-writer Jeong Seo-kyeong built in a number of devices to illustrate how truth, while seemingly shifting and obscured, might be divined. The town to which the detective retreats in the second half is famous for its persistent fog, and there’s a recurring motif of blue and green and how they can confuse, even switch places. A scene with a blue palette will give way to one in green, and vice versa. There’s even a dress the detective says seems blue one moment and green the next.

“We started out with these two worlds in mind: the mountain and the ocean. There’s a line about people who tend to like mountains and people who go for the ocean. The plot is structured to begin in the mountains and end in the ocean,” Park says. “In her apartment, the wallpaper, if you think those are mountains, it seems like a wide mountain range. But if you think they’re oceans, they look like small waves. The question of that natural environment is a very important motif, which connects to the colors green and blue.

The closeness of blue and green on the color wheel and their blending mirrors the film’s questions of truth or lies and love or utility.

“All of this connects to Seo-rae and how genuine her emotion is. It really depends on how you look at it. And there’s also the mist, which makes everything unclear and difficult to see. They’re all connected.

“The dress as well — we actually made three different versions; we have a bluer one and a greener one, and depending on the situation, we used those different versions. The audience themselves might think, ‘Oh, I remember it being blue, but now it looks green.’”

Amid that calculated confusion, Park employs his trademark tactile filmmaking to convey warmth, cold, texture and even the sumptuousness of food for a sensual experience. Moments of truth are caught when characters are captured on surveillance video and apps; they use translators and voice notes that sometimes reveal feelings they’re unwilling to admit directly.

“Our two protagonists refuse to express their emotions very clearly,” he says. The recording devices, like diaries, “can be described as the ears that listen to their honest feelings. As for the translating app, [it’s for] when they desperately want to express something quickly to the other person.

“It’s not just cold-blooded technology, but an extension of their own bodies. It is the box hiding their truth. I enjoy how the use of modern technology clashed with the classicism of the romantic elegance I was going for.”

Park’s movies are so meticulously constructed, the frames so beautifully composed and the camera movement so precise, there’s a kind of cool in them even when what’s happening is absolutely bonkers (as in “Oldboy”). But he never forgets the humanity of his subjects. Even in a noir that compels viewers to watch closely for clues, he finds the right beats to insert humor.

“I’m not a very funny person in my daily life,” he says, and he and his interpreter laugh, “so that is exactly why I’m looking for opportunities to always make the audience laugh. I think if the work is too serious all the time, it will come off as me trying to look cooler than I’m trying to be, a little more interesting and more serious than I’m meant to be, trying to come off as some artist.” They laugh again.

“I also think this is a more comprehensive method to show a life of a human being.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.