- Share via

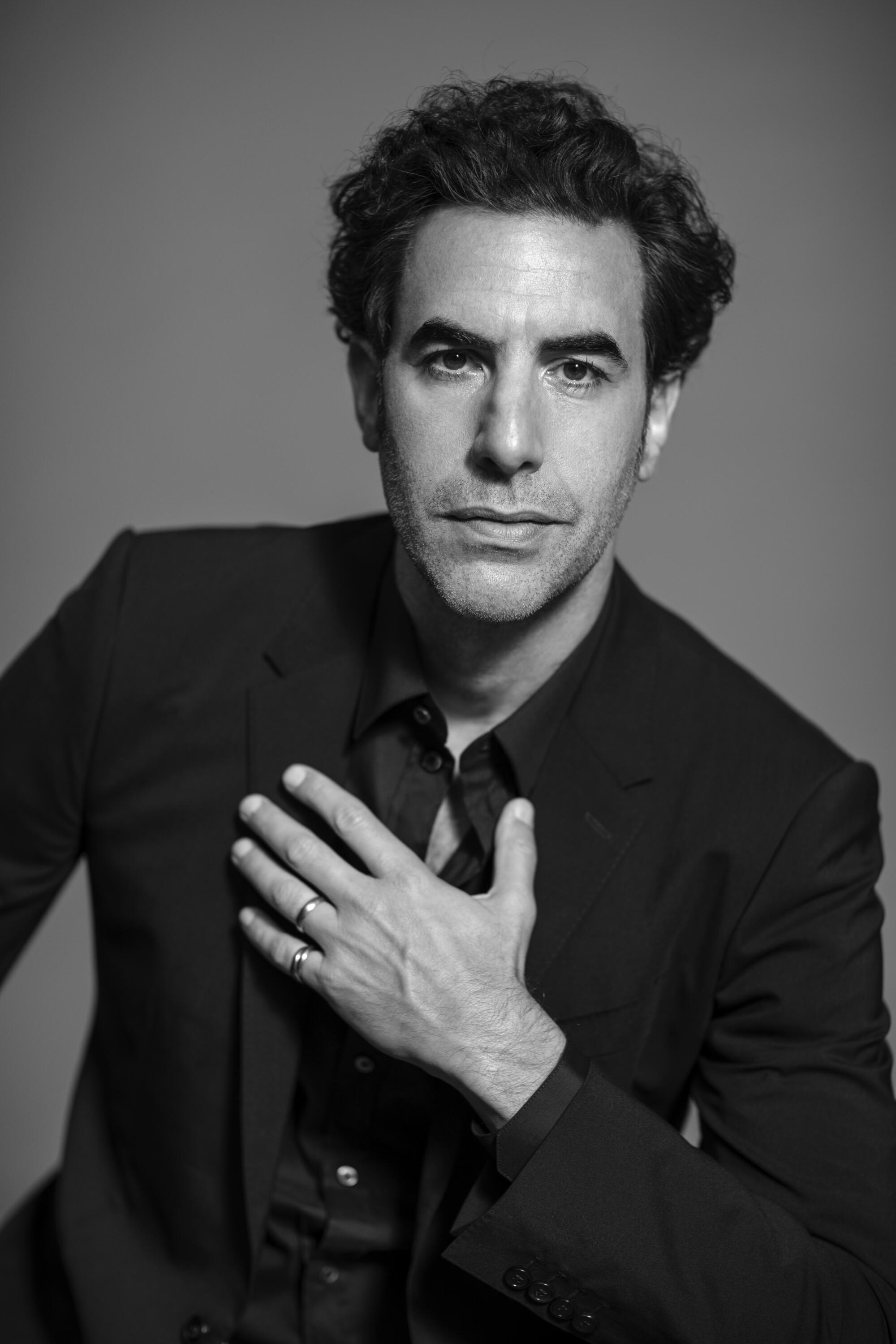

Sacha Baron Cohen was all set to play radical activist Abbie Hoffman in 2007. Steven Spielberg planned to direct the Aaron Sorkin script of “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” but the writers strike, among other things, scuttled that version of the project.

Your guide to awards season.

Get our Envelope newsletter for exclusive coverage, behind-the-scenes insights and columnist Glenn Whipp’s commentary.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Cohen moved on to make the comedy “Brüno,” and all of his research about Hoffman ended up becoming unexpectedly useful. “Brüno” ends with the title character, under the alias of “Straight Dave,” traveling to Texarkana, Ark., to stage a cage-fight match that would climax with him making out with his ex-boyfriend to pointedly illustrate the audience’s homophobia. Cohen’s attorneys cautioned him that he couldn’t go too far aggravating the crowd (“watch your hands, Sacha”), otherwise he could be charged with crossing state lines to incite a riot.

“And I was like, ‘I know about this law ... this is the law the Chicago Seven and Abbie Hoffman were tried for,” Cohen says, laughing. “In one way or another, I’ve felt very connected to Abbie through much of my life.”

We’re talking by Zoom on a winter evening, Cohen wearing a black baseball cap, black long-sleeve T-shirt and proffering a black humor. Director Jason Woliner, who worked on this fall’s wildly successful “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” (“it almost felt like we were this little band of bank robbers,” Woliner says of the secret process involved in making the sequel), says the first thing that strikes you about Cohen is “how deeply he cares about the issues he believes in.”

‘Borat Subsequent Moviefilm’ finds everyone’s favorite vulgar Kazakh journalist returning to the U.S. for the first time in over a decade, and things get ... political.

That passion is evident throughout our conversation, with Cohen repeatedly championing his causes: curbing defamation and disinformation on the internet and stopping Trumpism, which he views, now and forevermore, as an existential threat to democracy.

Of course, this being Cohen, the serious discourse often takes bizarre comic detours, musing on Stephen Miller’s bowel movements and the time he spent five days on the “Borat” sequel undercover with two QAnon conspiracy theorists and became so immersed in character that he forgot how to practice good dental hygiene. (“It was really hard to pick up the toothbrush and then I realized, ‘Oh, my god! I’m still Borat!’” Cohen says, adding that he literally slapped himself back to reality. And that was just Day 3. He still had another 48 hours to go.)

Cohen shot a chunk of “Borat Subsequent Moviefilm” before starting on “Chicago 7” in October. (“I didn’t know about it,” Sorkin says. “I found out about it the same time as everyone else.”) He returned to the project in the new year, in time to crash Mike Pence’s speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference in February, dressed as Donald Trump. The stunt required an intense amount of planning, Woliner says, because “there’s Secret Service everywhere ... and, you know, they’ve got guns.”)

“I’m often asked, ‘How does an actor prepare for a scene?’” Cohen says, deadpan. “And I prepared by waking up at 1 in the morning, driving to a motel, sitting in a chair for six hours while a prosthetics team changed my face to Donald Trump’s and then, yes, sneaking into CPAC and staying in a men’s lavatory for a number of hours.”

When I expressed surprise that he got in in the first place, he agrees before I can finish the sentence. “So was I! I couldn’t believe it!”

As to how he whiled away several hours in a restroom stall wearing a 54-inch-waist fat suit, Cohen explains: “I had a phone, and I had one Coca-Cola. And I put little lines on the Coke bottle for how much I could drink per hour. In the meantime, I became familiar with the inner workings of the right-wing man more than anyone around. I know their diets. They need more roughage. It was a little too lively in there.”

If not for Trump, Cohen would never have made a “Borat” sequel. Their paths first crossed in 2003 when Cohen interviewed Trump as wannabe-rapper-journalist Ali G, pitching him an idea for gloves to wear while eating ice cream. In 2012, after Cohen, costumed as his character from the movie “The Dictator,” dumped the cremation “ashes” of Kim Jong Il on Ryan Seacrest on the Oscars’ red carpet, Trump posted a video defending Seacrest, saying that Cohen “should have been put down fast.” Likely, this public show of support had nothing whatsoever to do with Cohen defecating in front of a Trump property in the first “Borat” movie.

“Borat” star Sacha Baron Cohen said on “Good Morning America” that he was concerned for actress Maria Bakalova during her scene with Rudy Giuliani.

“The new ‘Borat’ is really my form of peaceful protest,” Cohen says. It was imperative, he believed, to release the movie before Election Day to “sound the alarm.” When the pandemic and its subsequent lockdown happened in early March, Universal Pictures executives suggested delaying the movie to 2021 when movie theaters, presumably, would be open. But Cohen couldn’t shake the footage they’d shot of Pence dismissing the risks of the coronavirus during his CPAC speech.

“If this movie was going to be an indictment of Trumpism, I had to point to his biggest failure, which was his callous mismanagement of this crisis, leading to unspeakable death and catastrophe,” Cohen says. Amazon Studios bought the film, paying around $80 million.

“You know, it’s a bit of a challenge to talk about this movie without sounding a little pretentious,” Woliner says, laughing. “Can a comedy move the needle in terms of history? I don’t know. But that’s what Sacha was determined to do.”

Bulgarian actress Maria Bakalova knew she was in for a wild ride with ‘Borat.’ She even had to convince her parents the role was for a ‘legit’ movie.

“Somehow, Sacha is doing a revolution in the world through Borat,” adds Maria Bakalova, the Bulgarian actress who plays Borat’s daughter in the sequel. “And then you watch him play Abbie Hoffman, who dedicated his life to revolution. The similarities are huge. Their impact comes through this crazy, genius comedy.”

Cohen, 49, says his father had a biography about Hoffman in the house, but he didn’t read it as a young man and only became introduced to the activist while at Cambridge University, writing his college thesis on the Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights movement. Hoffman’s purposeful over-the-top theatrics — he once vowed to levitate the Pentagon, putting an end to the Vietnam War — resonated with Cohen, who, growing up in London, loved Monty Python, Peter Sellers and the surrealistic, subversive films of Luis Buñuel.

There was another connection: Cohen studied with the great theater and clown teacher Philippe Gaulier, who leads one of the few classes on the art of bouffon. Never heard of a bouffon? They were outcasts in medieval society who would be allowed back into the villages once a year to put on plays that mocked the establishment. “It was a very biting form of satire aimed at power,” Cohen says. “You’d have people with extreme deformities playing the king of France.”

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Hoffman, Cohen believes, followed the lineage of the bouffon during the 1969 trial in which he and the other defendants (originally there were eight) were charged with conspiracy and, yes, crossing state lines to incite a riot in the wake of violence at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Hoffman and fellow Youth International Party (yippies) co-founder Jerry Rubin (played by Jeremy Strong in the movie) would play pranks in the courtroom, provoking the judge and demonstrating they had no respect for the trial.

“Outwardly, he was a buffoon, but underneath it all was a deeply committed activist who was ready to risk his life to challenge injustice,” Cohen says. “He showed the power of humor to expose the ills of society.”

Sorkin describes Cohen as “joyful” and appreciated the spontaneity he and Strong brought to their courtroom scenes, though there were times when he needed to tell them to dial the antics down a notch.

“You’d hear me say things like, ‘Cut. That was great. Let’s try it again, but without the kazoo,’” Sorkin says. “There were any number of unexpected touches they brought in, but it energized everyone.”

Cohen continued obsessively studying Hoffman while making “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” emailing Sorkin almost every night about a new discovery. “I couldn’t help myself,” Cohen says. “‘What about this, Aaron? This is incredible. Shouldn’t we put this in?’ And very graciously, Aaron would reply to each email and say, ‘I think we got it. Let’s stick with this version of the script.’”

“But it’s hard not to fall in love with someone like Abbie Hoffman,” Cohen continues, “this incredibly entertaining guy who was ready to die for his cause. When they ask him what the price is and he says ‘his life,’ it almost brought tears to my eyes.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.