Filmmaker tracks the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in ‘The Dissident’

- Share via

Bryan Fogel had an “out of body experience” while accepting the 2018 Oscar for “Icarus,” his debut documentary feature about doping scandals in cycling. He’d traveled a winding path to the stage: moving to Los Angeles years earlier for stand-up and sketch comedy before co-writing and costarring in the hit play “Jewtopia.” “Winning the Oscar, I felt an obligation to make more stories that would have an impact on society,” he recalled in a recent video interview.

That fall he began another odyssey, one that culminated with the Christmas release of his second documentary, “The Dissident.” The film investigates the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi Arabian journalist who lived in America and wrote for the Washington Post before being captured, killed and dismembered at the Saudi consulate in Turkey by a hit team. U.S. intelligence agencies concluded Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman is probably culpable for the killing.

Fogel “crafted the story like a Jason Bourne movie” while exploring real-world issues stirred up by Khashoggi’s murder: freedom of speech, human rights, protections for journalists, Saudi propaganda and its cyberwar against its citizens and Americans.

“The Saudis had hacked Jamal and others, which is arguably why they decided to kill him — he was helping dissidents mess with the Saudi narrative on Twitter, which is how the kingdom controls the country,” Fogel says.

Two weeks after the Oct. 2, 2018, killing, Fogel was doing his first interviews but he knew the movie required sources out of his reach, such as Hatice Cengiz, Khashoggi’s fiancée; Omar Abdulaziz, the exiled young activist Khashoggi was helping fight the Saudis on Twitter; and Turkish officials and investigators. He initially turned down financing from the Human Rights Foundation, asking instead for assistance meeting sources. (Later, the foundation financed the movie.)

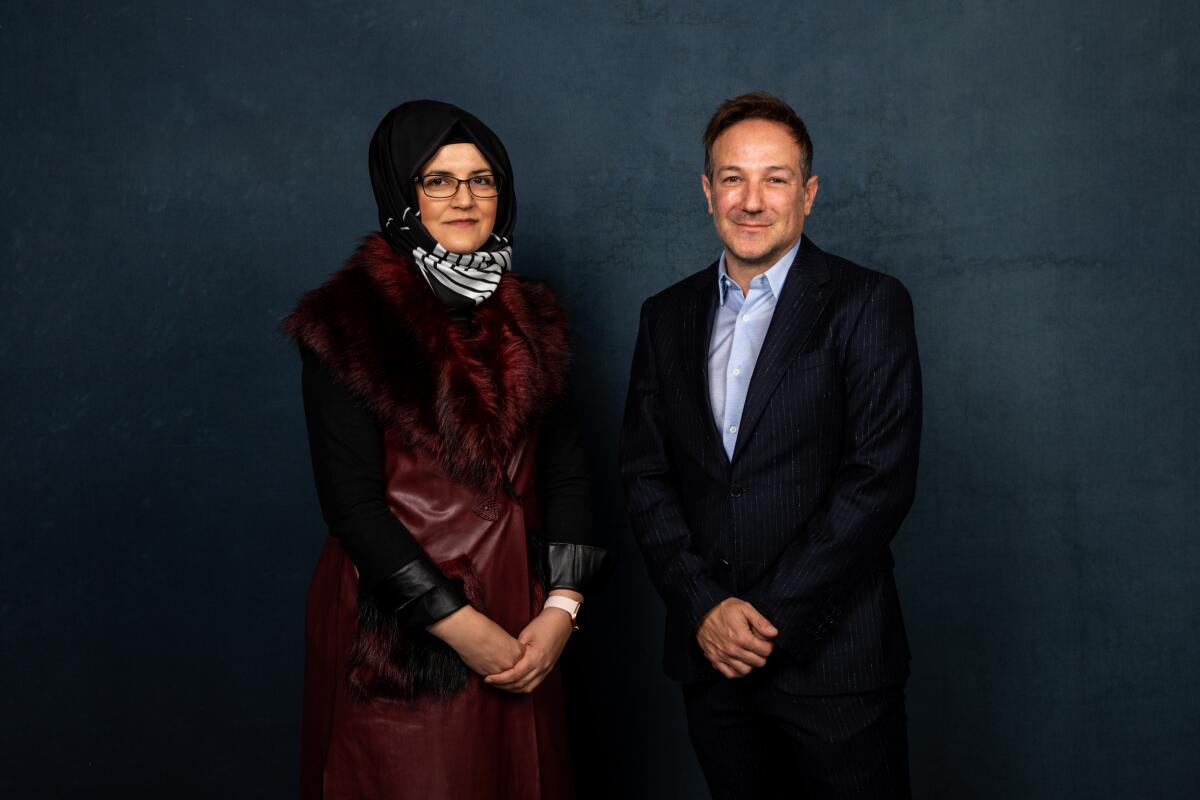

In November, he flew to Istanbul to meet with Cengiz and Turkish officials. “I spent five weeks there without a camera or a crew, just building relationships,” he says. “I met with Hatice eight times, building trust and a friendship.”

Cengiz was reluctant but didn’t say no. Fogel flew to Montreal, where Abdulaziz was equally hesitant. “I said, ‘Let me film you and we’ll leave you with all the camera cards and if you decide at some point you trust me, you can give me back the camera cards,” Fogel says.

Back home, Fogel persisted with Cengiz until February 2019 when she finally invited him to film her. A few months later, Abdulaziz also agreed to appear on film, handing back $40,000 worth of camera cards.

In Istanbul, the delays were more cultural. “There were no phone calls or emails — everything required a meeting,” Fogel says. “They’d say come meet this official in Ankur, just hop on a flight. And every meeting was a huge thing with tea, food, Turkish delights. It was 15 days of meetings for one day of filming.”

Still, his patience paid off, landing previously unseen police footage from Turkey’s investigation into the killing and interviews with a presidential advisor, a chief prosecutor and a police examiner who had not otherwise spoken out. His efforts to obtain the government’s transcript of the murder, which was caught in recordings from the room, finally worked too … three weeks before the movie’s January premiere at Sundance. He managed to incorporate some of the material for that screening but afterward spent months expanding those scenes and using more of the transcript. The Turks ultimately offered Fogel the audio of the killing but he declined. “It felt like exploitation,” he said. “We don’t need to hear that.”

The film earned raves at Sundance yet every major studio and streamer passed. “I was very disappointed by the fear and cowardice,” Fogel says. “It’s everyone — Netflix, Amazon, HBO, Hulu and all the theatrical distributors.”

“Saudi Arabia has one of the world’s largest sovereign funds for investment and they’re the money behind SoftBank and they invest in Hollywood,” Fogel explains. (Netflix previously capitulated to the kingdom, pulling a Khashoggi-related episode of Hasan Minaj’s “Patriot Act” in Saudi Arabia. The company recently reached a deal with a Saudi production company.)

Fogel believes “The Dissident’s” depiction of the Saudi hacking of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos made executives fearful of being hacked themselves and that because President Trump accepted Bin Salman’s denials, Hollywood was terrified that taking a stand would prompt attacks from the president. “He created an atmosphere of fear here and that has to play into it.”

Fogel believes a streamer may eventually carry the film since it wouldn’t have to brand it as original content. He’s also hopeful the film’s agenda will find a more receptive White House under Joe Biden. “He said he’d make it a priority to re-evaluate our Saudi relationship,” Fogel says. “And he was outwardly vocal about seeking justice for Jamal.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.