- Share via

To Mayor Daisy Lomeli, it’s fitting that Cudahy — one of the smallest cities in Los Angeles County — took the bold stance of passing a resolution calling for a cease-fire in Gaza, a month after war broke out in the Middle East.

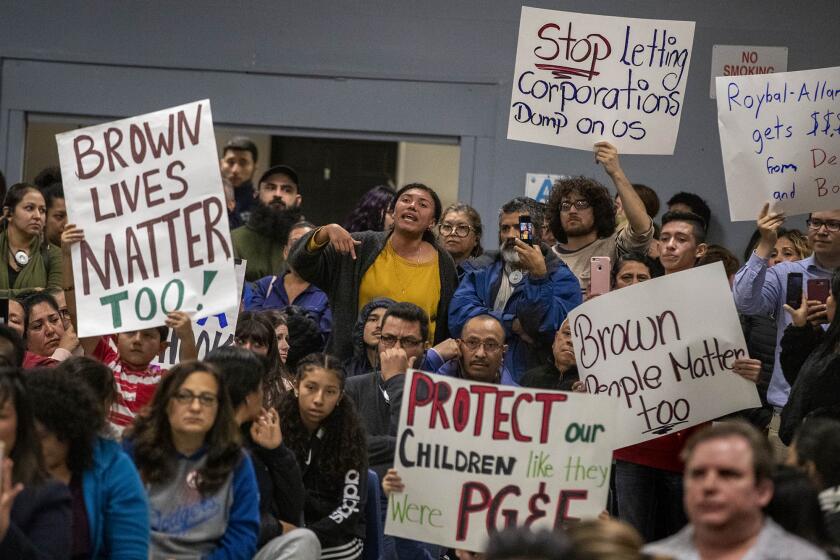

Cudahy is the first city in Southern California to support the Palestinian people of Gaza with a resolution that not only calls for a cease-fire, but declares Israel’s government as “engaging in collective punishment” in response to the Oct. 7 attack carried out by Hamas. The resolution passed on a 3-1 vote Nov. 7 after hours of public comments and deliberation.

An Orange County school district’s efforts to introduce lessons on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have ignited emotional discourse among Jewish and Arab American community groups.

The war was triggered by Hamas’ attack in southern Israel in which the militants killed about 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and captured more than 200 men, women and children, Israeli officials said. The Palestinian death toll — according to the Palestinian Health Ministry in the West Bank — has now mounted to more than 12,700, including more than 5,000 minors and 3,250 women.

The working-class, majority Latino town of Cudahy has a large immigrant population, which Lomeli said “can connect with the shared experience of Palestinian people in terms of the exploitation, the colonialism that was happening in their home country.”

Lomeli, 37, thinks of the city’s immigrant mothers who, through Union de Vecinas, organized to bring rent control to Cudahy this summer.

“What they’re seeing in the media is a lot of suffering of mothers. Moms in our community could definitely connect to being back in Mexico, back in Guatemala, also having to leave their babies with a trusted relative due to the state of violence in their community,” Lomeli said. “There’s that empathy and understanding for their suffering.”

With this declaration, Lomeli said it’s about “our community knowing that we do not stand with oppression.”

Now, other cities may be following suit, with the heavily-Latino city of Santa Ana expected to vote on a similar resolution at a city council meeting in early December.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said Santa Ana Councilman Benjamin Vazquez, adding, “Why is it allowable to kill Palestinian children?”

While Americans are split over Israel’s response in its war with Hamas, a rising number say Israel is going too far, according to a new NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll. It found that people of color and younger respondents were driving these results. “Their sympathies lie more with the Palestinians than Israelis,” according to an NPR report of the poll.

Latino Americans also have lower levels of Islamophobia compared to other ethnic groups, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding found by interviewing more than 2,000 people of different racial backgrounds and religions.

Latinos interact with American Muslims at school, work and in their neighborhoods; they find common ground in the negative media portrayals of their communities and in their pursuit of the American dream, according another recent ISPU report in collaboration with Latino Decisions and IslamInSpanish.

In the neighboring city of Bell, Ali Saleh, who is Muslim and of Lebanese descent, serves on the City Council. Lebanese Americans — some who fled civil war in Lebanon — make up a small community in Bell, with more living in Cudahy, Maywood and South Gate. A small population of Palestinians also live in Bell and in nearby towns.

With only about 22,000 residents, Cudahy is no stranger to making headlines.

Hundreds of Cudahy residents expressed outrage Friday over the Delta jet fuel dump, seen as part of a pattern of environmental injustice against the area.

The city made national news in January 2020 when a Shanghai-bound Delta plane dumped fuel over multiple schools while making an emergency landing at LAX, injuring children and teachers.

It became a flashpoint for Trump supporters who in 2017 protested the city’s “sanctuary” designation in protection of undocumented immigrants.

Prior to that, Cudahy’s council collapsed in 2012 amid allegations that city officials attended meetings while intoxicated, rigged elections and were part of an illegal sex business. Two council members and a city official were arrested by federal agents and charged with bribery.

Now, Councilwoman Elizabeth Alcantar notes, “the feel of the City Council is very different.”

The City Council’s three Latinas — Alcantar, Lomeli and Cynthia Gonzalez — voted in favor of the resolution. Councilman Martin Fuentes abstained, saying Rep. Robert Garcia, who represents Cudahy, should be the one to take a stance.

More than a week later, the congressman issued a Nov. 17 statement, saying he supports “negotiations to release all the hostages to secure a lasting ceasefire in Israel and Gaza.”

“Any deal must ensure that humanitarian assistance reaches the Palestinian people directly, and achieves both an end to the attacks on Israel by Hamas, and the protection of civilian life in Gaza,” Garcia said.

Inspired by U.S. Rep. Cori Bush’s Ceasefire Now Resolution, and Richmond, Calif. — the city believed to be the first in the country to pass a resolution in support of the Palestinian people — Cudahy’s resolution describes Gaza as “the world’s largest open-air prison” due to “unbearable living conditions imposed by the Israeli government.” It states that the city “takes seriously the entreaty of ‘Never Again,’ and that the historical memory of the Holocaust means fighting ethnic cleansing and apartheid everywhere.”

The city of Richmond voted to support the Palestinian people in Gaza with a controversial resolution after a marathon City Council meeting.

Leading up to the council vote, which was first covered by Los Angeles Public Press, organizations like the Israeli-American Civic Action Network denounced the resolution as “racist” and “anti-Jewish.” In their petition letter against the resolution, the network called it “one-sided” and said it “perpetuates harmful stereotypes.”

The network said the resolution “will sow divisions locally, throughout the State of California, and across the nation.”

Representatives with the Arab American Civic Council and the Council on American-Islamic Relations urged the council at the meeting to approve the resolution. Jews spoke in favor and against it.

While the resolution is largely symbolic, it also urged Garcia and the entire California congressional delegation to support a cease-fire.

“We always call on residents to reach out [and lobby] their local, state, or federal elected officials,” said Alcantar, 30, who grew up with Palestinian peers in high school. “This is a similar stance of Cudahy saying, ‘This is our position. We urge you to take the same position.’”

“City Council cannot change what is happening internationally, but our congressional representatives can,” she said.

Rida Hamida, executive director and founder of the group Latino & Muslim Unity, has been using Cudahy as an example for other cities including Anaheim and Santa Ana to take action.

“It’s so inspiring to see such a small city that has been disenfranchised and marginalized ... [and] yet they have been the voice of the intersectional struggle between Palestinians and Latinos,” said Hamida, who is of Palestinian descent and whose organization works to bring Orange County’s Latino and Muslim communities together.

The Santa Ana City Council is expected to take on its own resolution on Dec. 5. Hamida and other activists have pushed Anaheim — a majority-Latino city with a district of Arab-owned businesses — and Long Beach to do the same.

As Latinos, “we understand injustice,” said Cudahy Councilwoman Cynthia Gonzalez, 44.

Gonzalez, who works in education, points to the disproportionate COVID-19 impacts she witnessed working and living in South Central and Southeast L.A. — the unequal access to vaccines, pandemic misinformation, and the number of youth who prioritized work over school to financially help their parents.

She wonders if the jet fuel dump had occurred in a white and wealthier city, “would there have been more outrage?”

“They’re not dropping bombs on us, but Delta dropped gasoline on the community, and nothing came of it,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez grew up seeing her father juggle two jobs delivering newspapers and working as a manager at a foundry. She saw her cosmetologist mother organizing for immigrant rights through the Catholic Church at a time when checkpoints in the city of Maywood were nabbing undocumented drivers who didn’t have licenses.

To Gonzalez, it’s important to use their voice as elected leaders to uplift “the connection we share with Palestinian people in terms of the struggle.”

“We understand what it means to be left behind,” she said.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.