- Share via

It’s common to find dueling statistics within the Latino community that appear to disagree with each other. I recently wrote about new research showing that 78% of Latinos no longer believe the Spanish language is necessary to define Latino identity, while at the same time 54% of non-Spanish-speaking Latinos say they’ve been shamed for it. Here’s another interesting, seemingly conflicting pair of studies: LGBTQ+ identification is higher among Latinos than any other group in the U.S., and 44% of Latin LGBTQ+ youth have seriously considered suicide in the past year, according to new research by the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention group focused on LGBTQ+ youth.

These are harrowing statistics, and coupled with high femicide rates in Latin America and accusations of higher rates of sexism among Latinos in the U.S., bring to mind a word I’ve come to resent: machismo.

It’s a word that’s been used to bring a variety of behaviors and attitudes under one roof, like homophobia, misogyny, violent masculinity and more.

In light of recent data, it’s worthwhile to revisit the concept and see if it holds anything for us by way of explaining the social ills plaguing the community. Is “machismo” an appropriate diagnosis for these problems, or is it itself a stereotype used against Latinos?

Whether La Llorona is held up as a form of resistance against oppression, owning her power or reclaiming the monstrous bruja within, the narratives of the wailing woman have endured for centuries, reimagined into a radical icon.

Broadly speaking, I’m reluctant to discuss machismo. It’s a concept that, when centered in English-speaking media, often seems to take on a definition of “male chauvinism, but worse, because it’s being practiced by Latinos, a more dangerous kind of man.”

It plays on longstanding tropes of “aggressive Latin men” — the same sort of tropes that get deployed when, for example, it’s time to stir up anxieties over the sort of people who are crossing the U.S. border.

“Bad hombres,” if you’ll recall.

Such language is intertwined with racialized beliefs that cast Latin men as aggressive, uncivilized and driven entirely by their basest instincts. It’s much easier, especially for a U.S. politician looking to capitalize on prejudices, to cast the border situation as an invasion by lustful, barbaric beasts bringing their drugs and primitive culture with them.

The Día de Muertos parade is a sumptuous, extravagant delight. It might surprise some to hear that the parade stemmed from a single scene in a James Bond movie in 2015.

This is why, even when working in progressive English-speaking media in the U.S., I typically decline to talk about machismo. I don’t doubt there are good intentions, but the concept is built on a shaky foundation.

It’s also the case that, as with any culture, there are nuances and finer points to be made about how issues like homophobia or misogyny manifest in specific ways in specific environments.

It’s worthwhile to look into how these problems show up in everyday ways in our communities so that we might address them more efficiently in ways that are culture-specific. And when I look at anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment and misogyny in Latin American communities, I see, once again, contradictions and paradoxes.

Of course, when discussing LGBTQ+ acceptance in Latin America, it becomes necessary to separate different countries and groups. There are wildly different attitudes between, say, Argentina and Honduras when it comes to acceptance of LGBTQ+ people. It remains the case that, around the globe, wealthier nations tend to be more accepting of LGBTQ+ people.

Latino authors across Los Angeles are taking advantage of the resources offered by local libraries to jump-start their careers.

This makes sense, not because supporting gay marriage, to cite one example, is a privileged concern, or because people from poorer countries are inherently more prejudiced, but because a lack of resources tends to exacerbate other problems.

Living in economic instability often leads to an increase in religious attitudes and heightened suspicion of all sorts of “outsiders,” anyone who doesn’t fit in or belong, be it along the lines of sexual orientation, race or class.

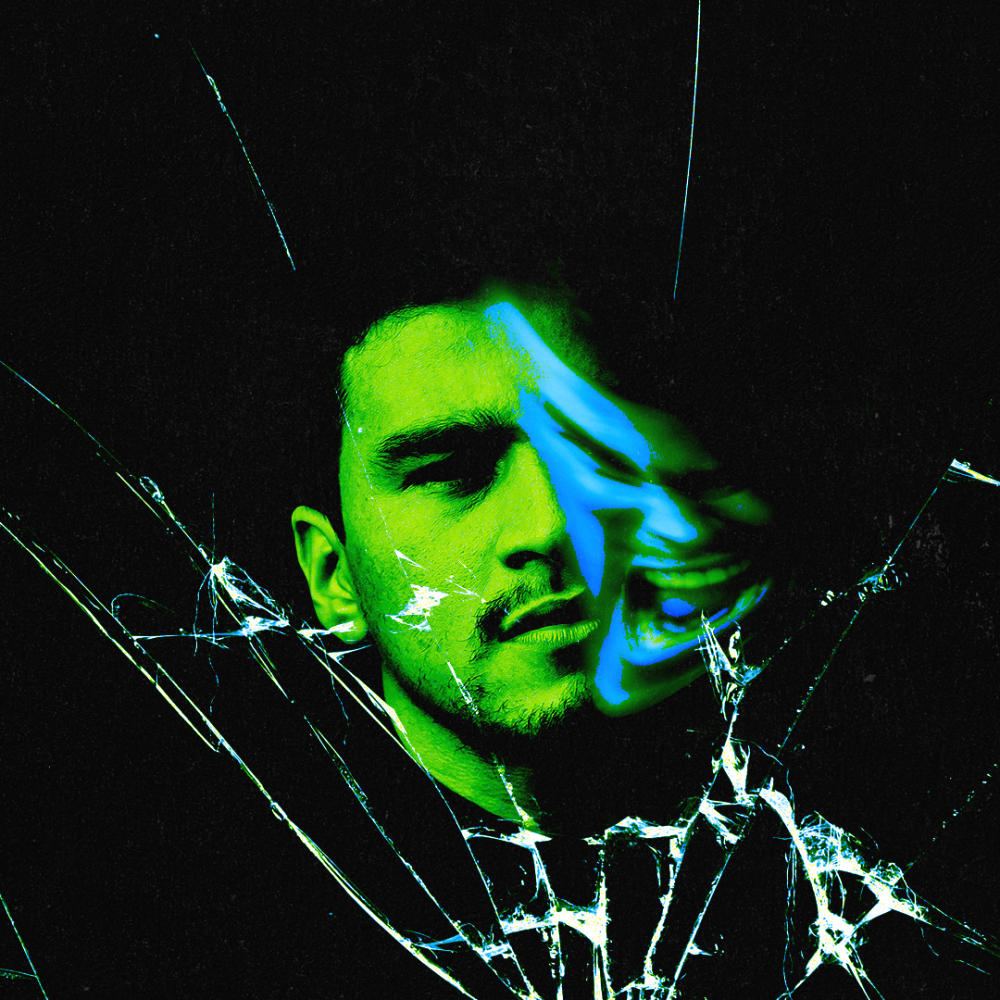

It’s something that’s observable beyond Latin America and Latinos in the U.S., which is why I’m so reluctant to give the concept of machismo too much weight in explaining the subjugation of women and LGBTQ+ people in these communities. On the other hand, as is often the case with stereotypes, they can be internalized, and there absolutely is a hypermasculine performance favored by Latino men that feels specific to Latin culture.

I once embraced it myself as a closeted gay Chicano kid in high school.

The show’s cultural impact is apparent, from our preoccupation with astrology to clips of the show making the rounds on social media.

The Latino macho, like any male chauvinist in the U.S., asserts himself by putting himself above women and men they deem effeminate. Dominance over the people and space around him puts him on a pedestal and validates him as strong, separating him from the weak who have to comply with his will. But it’s a double-edged sword.

He can’t express emotion or show vulnerability and must constantly police his behavior and self-expressions to make sure they align with the strict code of masculinity. It promises freedom but becomes a prison.

When I reflect on my life both as a Chicano and as a gay man, I see some similarities in struggles. The concept of machismo robs people of their interiority. It takes complicated human beings and boils them down to exaggerated tropes — just like homophobia does. Some of it comes from the outside, and some of it comes from within, but either way, it is dehumanizing.

Now, how any of this squares with public adoration of flamboyant figures like Walter Mercado and Juan Gabriel is a subject for another time. It’s another one of those paradoxes that make up the mosaic of Latino culture. But if another piece of that picture is machismo, it’s one we can do without.

Both for the sake of the people it hurts, and for the people doing the hurting. So often, they are one in the same.

John Paul Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets like the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He will write a weekly essay for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.