- Share via

In 1981, when Fernandomania first swept the country, I was 7, ignorant about the controversy surrounding Chavez Ravine or the Dodgers’ keen financial interest in finding a player to attract disaffected Latino fans. I only knew that I loved baseball and that my father, a Mexican immigrant, had once been really good at it.

In Fernando Valenzuela, I saw a composite of family members. He didn’t look like an athlete and my father didn’t either. Instead, Fernando sort of resembled my Tío Armando, my father’s youngest Chihuahua cousin, who sported a similar mullet as well as my father’s hand-me-down Budweiser shorts.

Fernando has been the subject of at least three documentaries, so his story is surely familiar. He went undefeated in his first eight pitching starts, a feat that had been unmatched in four decades, and he remains the only MLB pitcher to win the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards in the same season.

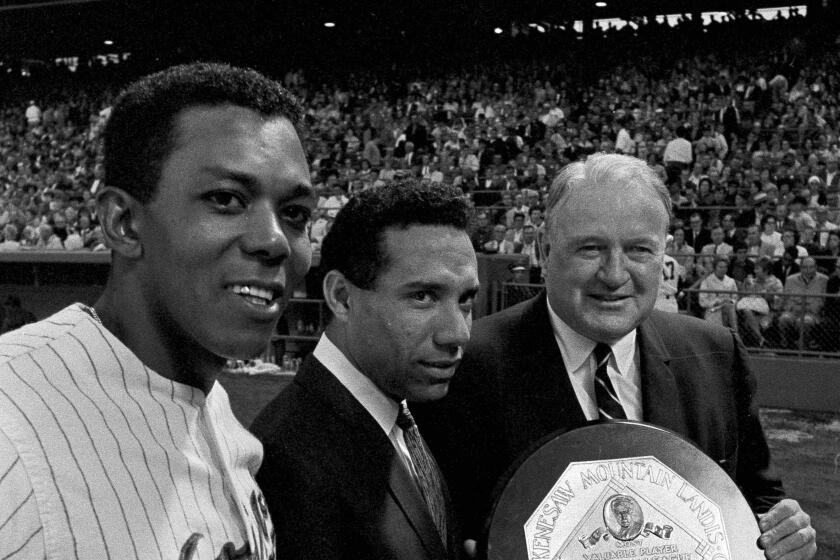

Zoilo Versalles and Tony Oliva were teammates on the Minnesota Twins. Both players were involved in a historic MVP race that would crown the first Latino MVP in the MLB.

From 1981 to 1986, he made six consecutive All-Star teams. He also grand-marshaled the East L.A. Christmas Parade just weeks after his 21st birthday, wearing an incredible buckskin-fringe jacket and high-crowned vaquero sombrero, no less. During this unprecedented streak of success, Fernando became such a cross-cultural phenomenon that he was even featured on a box of Corn Flakes, a distinctly “American” honor, even if the accompanying commercial only ran on Spanish TV.

Tomorrow the Dodgers will officially retire Fernando’s number, 34, placing it with those of the other retired greats adorning the rim of the Field Club level. His accomplishments will be celebrated across each of the weekend’s three games.

Fernando was the first Mexicano I witnessed having success in this country largely on his own terms. In the decades since, I’ve remained drawn to him for inspiration and persistence. I have my bobbleheads and my T-shirts and my buttons and pins. I have his Rawlings model baseball glove with a decorative signature stamped into the palm.

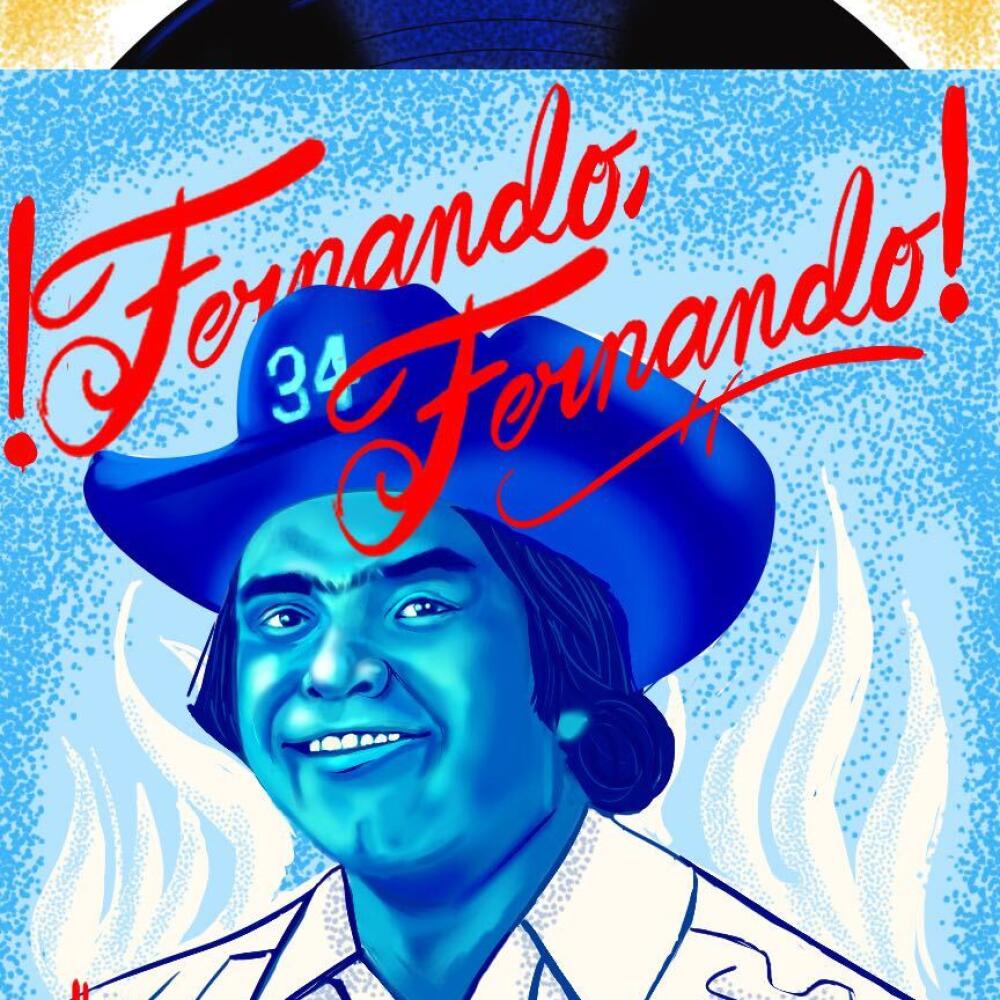

But of all my Fernando possessions, the most prized are the records featuring tribute songs. With so much cultural borlote around him, these were an inevitability, made by recording artists across a spectrum of talent and opportunistic savviness. They’re all from 1981 or 1982.

If I were to DJ an all-Fernando set, I would open with “Go Fernando” by Everardo y Su Flota. This disco-laced, midtempo salsa track is a popurrí, mashing up “La Bamba” with “Sonora Querida,” “Máquina 501” and “El Moro de Cumpas,” all shout-outs to Fernando’s home state. The song shifts somewhat awkwardly between parts, but remains funky enough that my Tía Lupita, who dances at every party, would probably start the pachanga and would soon have everyone chanting “¡Go, Fernando!”

Next, I’d play “Cumbia a Fernando Valenzuela,” either the version by Chalo Campos or Los Gatos Negros. I love that both are reminiscent of a band I might have hired to play for my parents’ 40th wedding anniversary — picture 10 dudes in identical powder-blue polyester suits. Between the two tracks, the edge goes to Campos for fitting in, mid-song, a mock interview with Fernando. Campos, as Fernando, is asked how many batters he’s struck out. The reply, delivered con confianza: “¿Hablando en serio? Todos.”

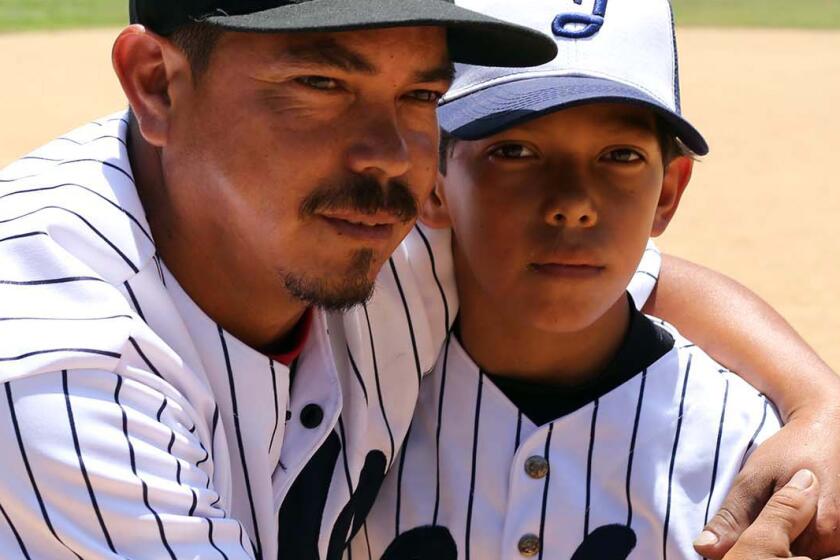

A father and son reunite in Carson after three years apart

I especially cherish the corridos that paint Fernando in boastful, epic terms. Rafael Buendía, the Mexican ranchera singer, also known as “El Compositor de los Pobres,” opens his album, “Arco Iris,” with “Fernando Valenzuela (El toro de Sonora).” An original composition by Buendía, this plucky, chugging track touches on Fernando’s pitching prowess and contains my favorite smack-talking verse of all time:

“Un pochador de primera/eso nadie se lo quita

Tesoro de nacimiento/su brazo trae dinamita.”

For a more reserved take, try Conjunto Michoacán’s “Corrido de Fernando Valenzuela,” which would have you believe that Fernando’s on-field success could be attributed to his having a noble heart, caring for his parents and being an all-around good guy. On the other hand, in “El Pitcher Valenzuela,” Los Rancheritos de Michoacán cast him in a different, fiery light. The instruments on this track are plucked with a percussive intensity matched by its vocals: “¡El es Mexicano! ¡El es Valenzuela! ¡Y a todos los gringos, vino a conquistar!”

Not every tribute aspires to such greatness. There’s a release on Screwball Records, the winking reference to one of Fernando’s pitches already a red flag. The single is made even more dubious by the group’s name — Los All Stars. The “Los” sounds forced and has as much cultural nuance as the “specialties” section of a Taco Bell menu. This might work under certain conditions, only the music’s not great. The ballad’s lyrics settle into a series of simplistic couplets set to the tune of Marty Robbin’s 1959 country hit “El Paso.” This one should probably be avoided.

Bill Momone’s “Sign a Ball for Me” is an even greater curiosity. The song’s English version is another tepid ballad, amiable perhaps, but also historically inaccurate. Contrary to the first verse’s claims, Fernando didn’t arrive in Los Angeles throwing screwballs. He learned the pitch here, from “Babo” Castillo, a teammate from East L.A. Still, celebrating strikeouts is the definitive lyrical trait of any Fernando tribute song and this one manages to hit that mark.

The flip side, “Firma una bola para mi,” occurs in poorly translated, overly wordy Spanish. It also adds some warmed-over, “Ring of Fire” trumpets to ensure that its “Mexican-ness” is legible in a Fiesta Village sort of way. By today’s standards, it’s misguided at best, but the sincerity in Momone’s delivery makes me wonder if perhaps, four decades ago, the track was intended as a gesture of cultural respect. Depending on my mood, this song is either total garbage or falls into so-bad-it’s-good territory.

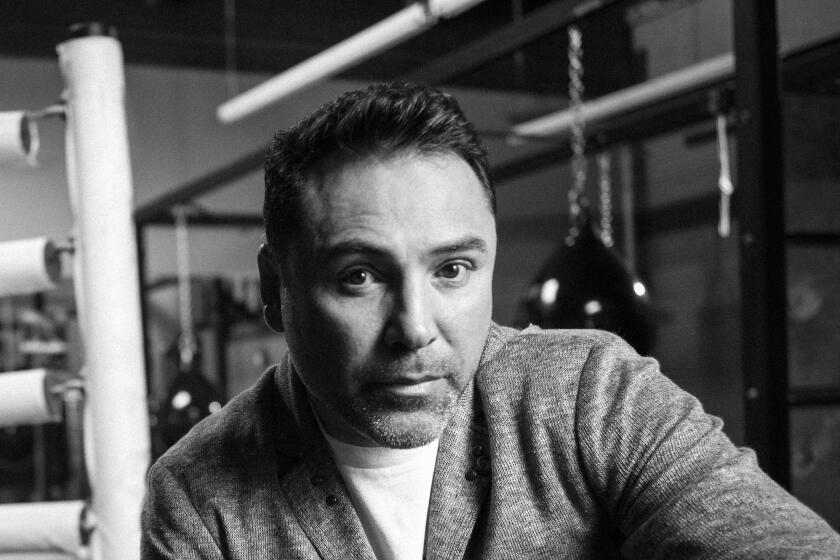

A new documentary on Oscar De la Hoya takes a look at his triumphs and demons and the sometimes difficult relationships in Latino families.

Beyond simple nostalgia, each of these songs are touchstones in my appreciation for all Fernando represents. When discussing him, folks tend to begin with the Chavez Ravine controversy, and rightfully so, but stopping the exploration there ignores the larger social forces with which Latinx people have always had to contend. I imagine the ongoing fervor around Fernando as a response to generations of racist hostility, an inversion of it all.

My affection for Fernando is as much about my mother’s memory of being struck with a ruler at school whenever she spoke Spanish, or her decision to name me “Michael,” when at home she’s always called me “Miguel,” as it is about anything Fernando might have done on the field.

Still, to have seen Fernando succeed and contribute meaningfully at the highest level, is to have witnessed living mythology. He’s a hero I can point out to my son when we get to Dodger games — Fernando as a tiny figure over in the broadcast booth, providing Spanish color commentary for gente listening on KTNQ, AM 1070. “Look,” I always tell my son, “allí está. Right over there.”

The tributes Fernando inspired still speak to me in existential ways, especially now, raising a son in a country well stocked with red hats. I want him to know that he is capable of greatness. And I want him to believe that greatness can be achieved on his own terms. For the models they offer my son, these songs have circulated in our lives, on our way to the Peck Road batting cages, to Little League games and, of course, to Dodger Stadium. They set the mood on the drive in, keeping things light and hopeful. On the drive home, my son sings along from the backseat, his voice calling “Fernando, Fernando.”

Michael Jaime-Becerra is an associate professor of creative writing at UC Riverside and author of “Every Night Is Ladies’ Night.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.