- Share via

It’s difficult for any museum concerned with anthropology to avoid making a monolith of its subject. Race and ethnicity are shoddy constructs encompassing disparate individuals, each with their own unique experiences and points of view. The headache is figuring out how to sensitively assert them as a cohesive whole so as to make their contributions more legible to a casual observer.

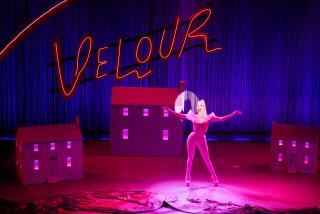

For the fledgling National Museum of the American Latino, this task is a full-on migraine, one exacerbated by right-wing critics who have taken offense to, among other things, the inclusion of a drag queen in a recent exhibit.

For Chicanos in particular, the sweet treat has become a mascot. But what is it about the concha that has elicited such fanfare?

To be clear, the museum does not exist yet. Its premiere exhibition, “¡Presente!,” opened last month in the Molina Family Latino Gallery of the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., and offended Republican lawmakers to such an extent that its federal funding is now under threat.

Republican Rep. Mario Díaz-Balart of Florida said he was “deeply disappointed” by the exhibit. A takedown published by the Heritage Foundation laments that the exhibit was “unrelentingly leftist” and “depicts Hispanics as America’s victims, as army deserters, drag queens, and traitors.”

I haven’t visited the exhibit, so I can’t speak to its quality. But of particular interest to me is the objection to its incorporation of Colombian American drag queen José Julio Sarria, otherwise known as Absolute Empress I, the Widow Norton, Empress José I and the Nightingale of Montgomery Street. That’s quite the mouthful, diva! The San Francisco drag queen notably became the first out gay person to run for public office in the United States in 1961.

It should come as no surprise to hear that Republicans are not the biggest fans of drag queens at the moment. As a gay Mexican American, I of course condemn the ongoing attempts to erase LGBTQ+ people, particularly transgender and gender-nonconforming people, from existence.

But I don’t want to simply write off critics of the “¡Presente!” exhibit as bigots.

Learning Spanish wasn’t part of a quest for identity. I was proud of this fact; that I was pursuing fluency on my own terms and not for cultural credibility.

I don’t think that’s productive, and anyway, I think it would be more interesting to use their response as a springboard for a discussion on how Latinos in the United States see themselves and, further, how any group of people go about trying to author their story. Not unlike how, say, a national museum might do.

One thing I would grant critics in this case is that there does exist in progressive circles a certain fetish for victimhood, an appetite for imagining historically marginalized groups as noble (perhaps even “uncivilized”) peoples with indomitable spirits and a collective yearning for freedom. This tends to elide the truth that within any group of people there exists the capacity for cruelty, a willingness to collaborate with the powers that be to the detriment of their own population, to replicate hierarchies that place oppressed groups within oppressed groups at the bottom for personal gain.

Of course, dabbling in some form of romanticization is hard to avoid. A museum dedicated to a historically marginalized group will obviously focus on the institutional hurdles and disenfranchisement that led that group to politically organize themselves into a coalition in the first place. In that process, the question of victimhood is bound to arise and, sure, there are ways to go about that that are patronizing or condescending. I can understand the discomfort in that.

But particularly among the political right, there is an equivalent urge to portray marginalized individuals as patriotic folk heroes. These are barely people; rather, they are symbols who overcome systemic issues like racism and xenophobia not with political organizing, but with hard work. The Latino success story, through this lens, is one of assimilation. The successful Latino pulls himself up by his bootstraps, loves and serves his country, and seeks to enrich it with his contributions. The successful Latino criticizes nothing, because the successful Latino is grateful, dedicated and self-reliant.

Club Tempo is the main precursor of L.A.’s cowboy gay scene, located on Santa Monica Boulevard and Western Avenue.

That’s why it’s funny to me that, under this criteria, José Julio Sarria fits the bill. In addition to being a drag queen, Sarria served in World War II and became a staff sergeant. He worked hard waiting tables and nurtured his dreams of being a performer. When he saw things happening in his country that he didn’t like, he worked within the system and ran for political office. Although he did so in a wig and pumps, Sarria walked the walk that so many right-wing Latino politicians are constantly preaching.

I’m not saying the inclusion of Sarria in the exhibit is the only objection Republican Latinos have to “¡Presente!” I’m saying that Sarria’s very existence, the way he moved through the world, troubles the right-wing narrative about what makes a “good Latino,” a Latino worth celebrating and holding up as a symbol of “who we are.”

Because, really, regardless of political affiliation, that’s what any group of people are: a narrative, held together by a loose combination of myths and material conditions.

The desire to erase LGBTQ+ people from various histories is nothing new. It happens here in the United States outside the parameters of race and ethnicity. Teaching LGBTQ+ history remains controversial to this day, and I think it’s obvious why. They don’t fit the narrative many in the U.S. want to tell about their nation’s past. It’s not that LGBTQ+ people didn’t participate in U.S. history. They did. It’s that many people prefer to pretend otherwise, calling inclusion of LGBTQ+ people in history “political” without acknowledging that their erasure too is “political.”

The organization’s founders saw a need for an LGBTQ+ youth mentorship program, so they set out to create one where Latinos and others could feel accepted.

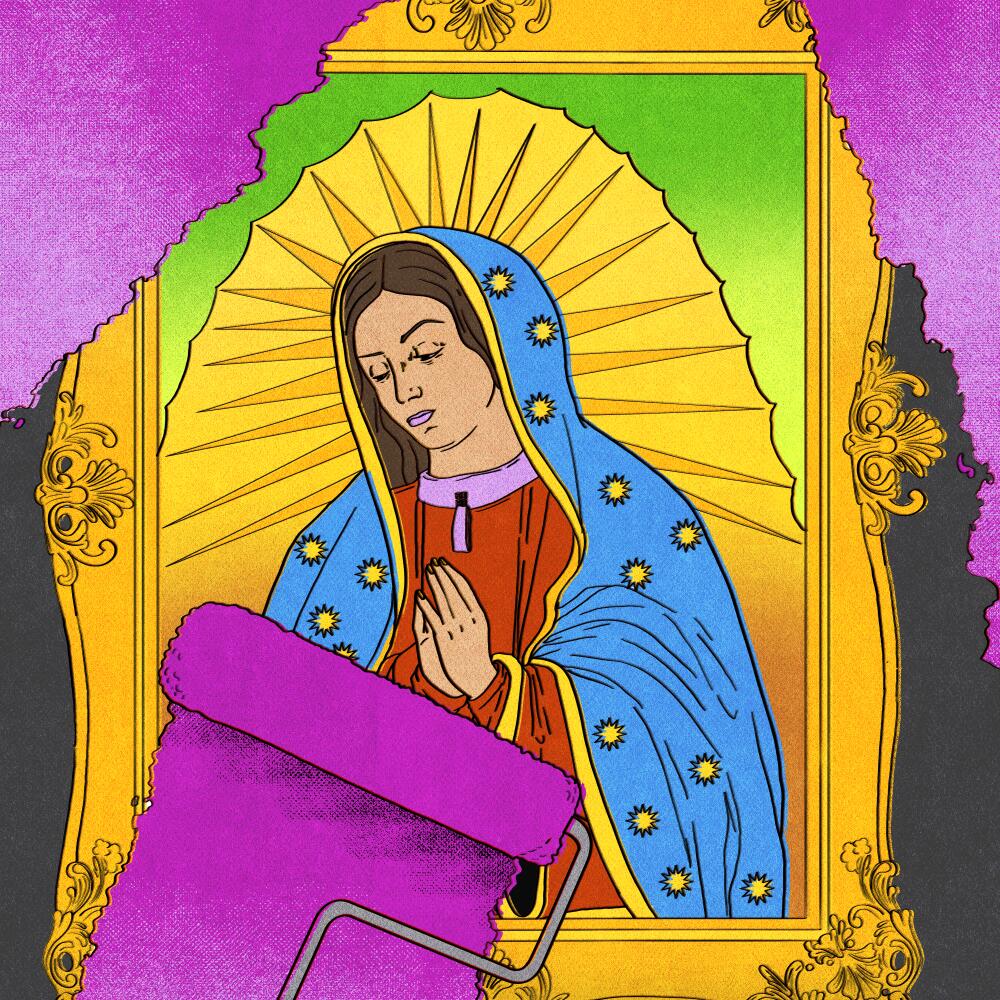

What is a Latino? What is an American Latino? What makes a Latino person worthy of learning about? These are difficult questions bound to cause disagreements. The fighting over the Museum of the American Latino makes sense. People care about identity, and a museum must set about ossifying the nebulous concept of collective identity into something tangible, something with plaques, displays and exhibits. It’s serious stuff.

But personally, what I love about drag queens is that they turn identity on its head. They make the implicit explicit. There’s something honest about all those layers of makeup. They remind us that identity is performance, that it is self-determined and, in many cases, silly. For me, I find a lot of lovely symmetry between drag and, say, mariachi attire and iconic figures like Juanga or Walter Mercado.

To call yourself Latino is to place yourself in a cultural context, to assert that you are a part of a people’s story, even if you don’t all look or think the same way. It’s a chaotic thing that relies on performance and a sense of responsibility to your community. I’d like to think, putting it that way, that critics might have more in common with José Julio Sarria than they’d care to admit, if they bothered to learn more about him somewhere.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.