- Share via

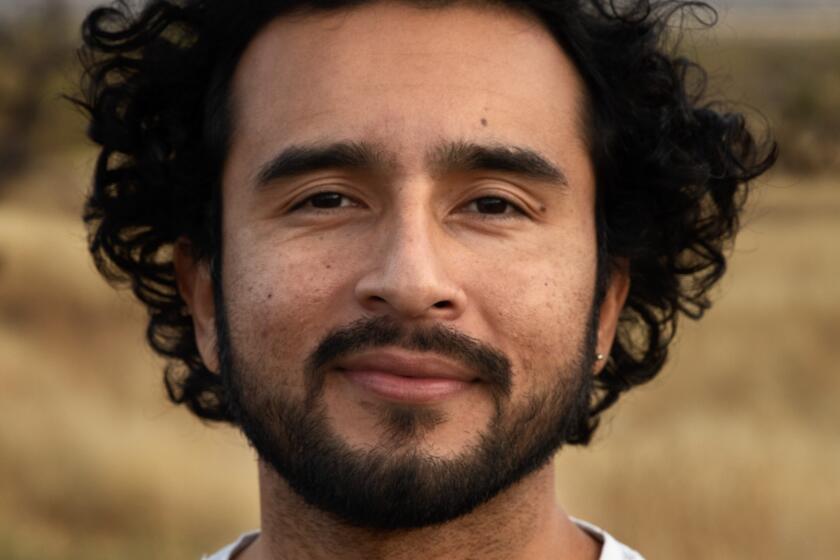

Growing up during the Salvadoran civil war, I learned from my parents that poets and writers are often at the vanguard of justice and change. Years later, after we emigrated from El Salvador to San Rafael, Calif., they taught me to revere names like Roque Dalton, Claribel Alegria, Amada Libertad and Manlio Argueta.

When I started writing poetry as a 17-year-old, my parents warned that my life could be at stake because many writers were considered enemies of the right-wing Salvadoran military government. At the time, I thought their warning might be parental hyperbole, but it also reminded me to take my writing seriously and to fight against injustices.

As I was finishing my MFA in poetry, I began to submit my first poetry collection to prizes whose award was a book publication. But over and over I ran into a variation of the following sentence: must be a U.S. citizen to apply.

This was 2014, and out of the 15 or so first-book poetry contests I was aware of, around 12 had this requirement. I was surprised to learn that the art my parents taught me was at the forefront of liberal thought in Latin America seemed to be guarded, in the United States at least, by systems and institutions intent on excluding writers like myself.

Becoming your family’s translator of what life is like in El Salvador and the realities of the U.S. takes a toll.

Their policies replicated the vitriol my family and I experienced almost daily as undocumented people at first, and then, as Temporary Protected Status card-holders.

A classmate, Christopher Soto, had organizing experience and together we huddled with another previously undocumented writer and friend, Marcelo Hernandez Castillo. Soto convinced us to first email the organizations including the Yale Younger Poets Prize, APR Honickman, National Poetry Series and the Andres Montoya Poetry Prize, about their eligibility requirements.

More than half of the organizations quickly replied and immediately changed their policies. Five others explained that board members first had to vote on the matter.

The Academy of American Poets seemed focused on what “American” meant for their Walt Whitman American Poetry Prize. Once conversations over email hit an impasse, Soto, Hernandez and I, crafted a public petition 800 writers eventually signed that became known as the Undocupoets Campaign asking for a just and fair change to these citizenship requirements.

We succeeded and by 2015 even the Academy of American Poets revised its wording and made its poetry contests open to everyone regardless of citizenship status.

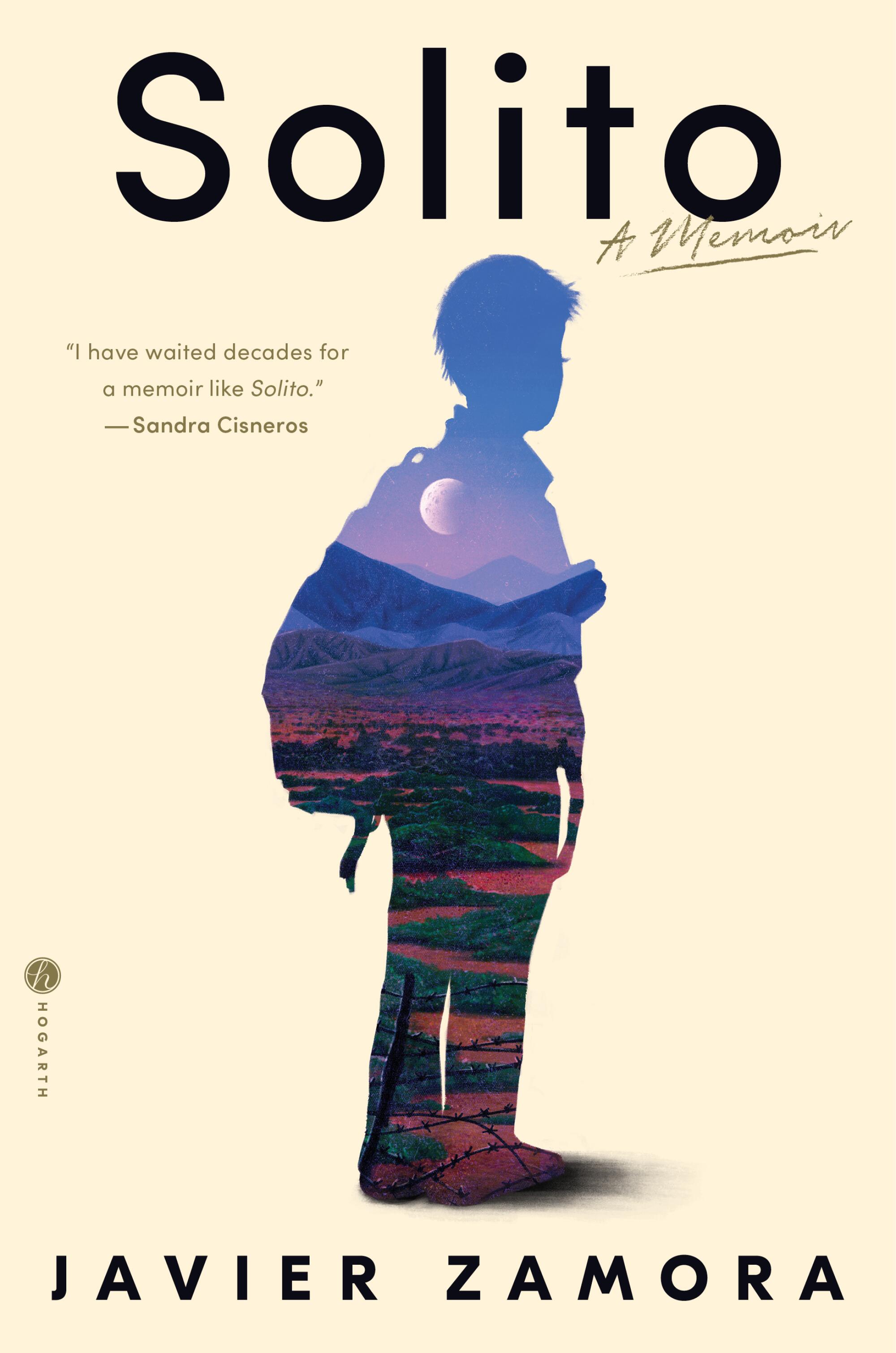

Javier Zamora talks about “Solito,” his harrowing memoir about journeying from El Salvador to the U.S. as an unaccompanied 9-year-old.

This shift is important because it shows any writer that your immigration status, just like your sexuality, gender, race and disability status, should not limit or define you.

As a child of leftists, I grew up believing this is how the world should be, where prizes that honor the “best” of any genre judges everyone equally in any given competition. Leaving certain people out does everyone a disservice because it limits diversity of thought and perspectives, therefore devaluing the competitions and hobbling their impact.

There is power in differences. There are creativity and invention in diversity.

The Undocupoets Campaign was solely concerned with opening poetry publication prizes to noncitizens. What I didn’t understand was that many more grants, fellowships and post-publication prizes still require “proof of citizenship.”

When my first book of poems, “Unaccompanied,” was published in 2017, I went through the awards cycle not knowing that the book couldn’t even be submitted to some of the biggest literary prizes such as the Pulitzer and the National Book Awards.

With varying artistic criteria, each year these organizations honor the best books with money, prestige and attention that can not only change an author’s career, but also expose their art and ideas to a national audience.

When my collection was published, I held Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a status that is completely up to the executive branch to keep renewing every year (similar to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA).

The then president kept threatening to abolish TPS and DACA and literary awards were the last thing on my mind. Even if I had known of the prizes’ requirements, I don’t know if I would’ve had the mental capacity to write a letter like this one.

In 2022, I published my memoir and second book, “Solito.” Months before, my editor and agent explained that because I wasn’t a citizen there were prizes I wasn’t eligible for.

I was disheartened and surprised to once again encounter this “checking of papers” in the literary arts — a field I truly believed to be a liberal haven and different from the xenophobia that persists in this country.

After 19 years here without a green card, then four years with an EB-1 “Einstein Visa,” after earning a master’s degree in writing from New York University and fellowships from Harvard and Stanford, I still wasn’t enough to be equally considered among my literary peers.

In 2018, the PEN/Faulkner Award changed their requirements to allow “American permanent residents and Green Card holders.”

In the same year, the National Book Awards, while they didn’t change their U.S. citizenship requirement, they did allow for exemptions if the writer could answer yes to these two questions: “Does the author consider themselves: an American immigrant who is currently and actively engaged in pursuing citizenship, OR legally unable to pursue traditional pathways to citizenship at this time?” AND “Has the author lived in the US for 10 or more years as of November 30 of the Awards year?”

These changes by both organizations are a step in the right direction, but the PEN still makes it impossible for undocumented writers to submit their work, and the NBA asks a lot to be considered for a literary prize.

Notably, the Pulitzer Prizes, arguably the highest profile, most important literary, artistic and journalist prizes in the U.S., remain closed to writers like myself — someone who has lived in this country since I was a child and who writes about the quintessential American topic, coming to America.

As someone who wanted to break into journalism with no connections, I was able to access people through Twitter I’d never have been able to without the social media platform.

On the website the following is displayed: “In the Fiction, Biography, Memoir, Poetry and General Nonfiction categories, authors must be United States citizens. In the History category, the author may be of any nationality but the subject of the book must pertain to United States history.”

Curiously, the Pulitzer Prizes for journalism are all open to noncitizens.

Once again I found myself angry and disheartened at the literary community, a community my parents taught me I should look to for refuge and acceptance.

After 19 years in this country and with all I had worked to achieve, I still wasn’t enough to be equally considered alongside anyone who has the privilege to have been born in the United States. In other words like a human being.

As a previously undocumented person, all I’ve ever wanted was to be considered the same as everyone else. Defined by my merit and not by the place of my birth or the lack of “documentation.”

As I’m writing this, marriage is still the quickest and most common path to citizenship in this nation. My one true vow I kept since I was undocumented was that I refused to get married for papers. I’m not the only undocumented or previously undocumented person I know who thinks like I do.

It’s our own private battle against an arbitrary, unjust and dehumanizing immigration system. It’s this hanging thought that has eaten away at my conscience, making me blame myself for lacking the name of an American city on my birth certificate.

Ironically, two weeks ago I received an email from the Pulitzer Judging committee asking me to be a judge for its 2023 Autobiography/Memoir category. A huge honor indeed and one that would’ve put a previously undocumented person at the table where voices are elevated and celebrated. In my reply I wrote: I cannot judge a prize that undocumented, previously- undocumented, and green card holders cannot win because of an unjust policy.

What I wanted to say was that I’m tired of the exceptionalism that is ingrained in American culture — a learned belief that separates, excludes and diminishes as it pretends to elevate. Even my immigration status describes me as “extra-ordinary,” more than, above others.

Especially now, when the end of Title 42 is reminding us that the U.S. immigration system is still broken and has once again failed to view immigrants as human beings deserving of dignity.

It makes no good sense that seemingly liberal organizations like the Pulitzer Foundation that frequently celebrate writers and artists whose works expose injustice, would simultaneously be perpetuating the kind of exclusionary xenophobia immigrants experience daily.

Opening these prizes, like opening borders, is not going to diminish the quality of the winners or of the people within this nation. Even past winners of all of the above mentioned prizes have fought for injustices like Greg Grandin, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, to name a few.

Other past winners, including the recent Pulitzer winner Hernan Diaz, have been legal permanent residents before they won these literary prizes.

While I declined the invitation to be a Pulitzer judge, I did leave the email open for a conversation should the board want help revising its requirements. The board replied that it couldn’t change anything and it was up to “the higher ups” in the board.

I hope they read this and reconsider their outdated policies.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.