They waited and waited for an evacuation order. The fire came first, and people died in Altadena

- Share via

During the night of the devastating Eaton fire, Altadena resident Araceli Cabrera and her partner remained on edge as they monitored the county’s Genasys emergency communications app.

“‘I’m looking at the app and we’re good,’” Cabrera, 52, recalled her partner saying well into the night. But around 4:30 a.m. on Jan. 8 — about 10 hours after the fire ignited — Cabrera saw a photo shared on Facebook of several fires burning within blocks of their western Altadena home. She and her partner looked outside in a panic.

“All of a sudden it was completely black and I saw the embers — part of me couldn’t believe it,” Cabrera said. “I felt like I was going to die if I didn’t hurry.”

The couple frantically decided to flee their home, yet it would be at least another hour before emergency management officials issued an evacuation order for their neighborhood. They ended up, like so many others, losing their home.

“I feel like different agencies failed us,” Cabrera said. “Nowhere did they say the fire was moving faster, they didn’t tell anyone to evacuate. ... It was like we were abandoned.”

Stories like Cabrera’s have ricocheted around Altadena in recent days as residents compare notes about evacuation orders that were issued hours after the massive Eaton fire ignited and — in some cases, after neighborhoods had already begun to burn and well after other nearby areas were ordered to leave.

The Times reported last week that thousands of people living west of North Lake Avenue first got electronic evacuation orders around 3:30 a.m., well after smoke and flames were threatening the area. All 17 people who died in the Altadena firestorm lived west of North Lake Avenue. The revelations have sparked calls for an independent investigation into what went wrong.

But some got even later alerts. Where Cabrera lived in west Altadena, residents weren’t ordered to evacuate until almost 6 a.m. on Jan. 8 — about 10 hours after their neighbors east of North Lake Avenue were ordered to leave the day before at 7:25 p.m., according to records of archived alerts.

In this section of southwestern Altadena — the Calaveras zone — the first evacuation order was not issued until 5:42 a.m. No warning preceded it.

Lauren Shurney’s childhood home, also in this area, somehow survived the devastating Eaton fire, but her mother will never return there.

Priscilla Shurney, 73, died two days after a chaotic evacuation from her longtime home as the Eaton fire invaded the neighborhood. Her family believes her death could have been avoided had officials issued timely evacuation alerts and updates.

“Had she not gone through all the physical trauma of being tossed around the way we had to [evacuate her] — not by choice — she would still be in that room with my dad and her caregiver,” Lauren Shurney said.

Many residents of western Altadena — which was shaped by discriminatory lending practices in the 1960s and 70s and has become known for its strong Black community — say they feel forgotten.

“The area was hit so hard and wasn’t notified properly, ... predominantly the old, multigenerational Black families,” Shurney said. “If you look at Altadena, it doesn’t look like anyone gave a damn about Altadena.”

On the night of the fire, Shurney was helping to care for her mother, who had suffered a stroke and relied on several medical devices to feed her and assist with her breathing.

Had officials issued timely alerts, Shurney said she would have been packing up and arranging for her mother’s extrication. As it turned out, it wasn’t until nearly 6 a.m. the next morning that Shurney and her family realized they needed to flee and ran down the street looking for help.

After a report from The Times, officials have called for an external review into delayed evacuation alerts in western Altadena, during the Eaton fire.

“It took five of us to lift her in a fitted sheet and put her in a wheelchair and wheel her to the curb where the car was,” Shurney said. She recalled looking at her mother’s limp body slumped over in the car and worried the drive would kill her. She called 911 and begged for a transport, but said the operator told her they were “a little tied up right now,” before hanging up.

Priscilla Shurney made it to the hospital, but died two days later. Her death has not been counted among the Eaton fire’s official death toll, but her family is adamant that the fire — and the lack of official warnings — killed her.

“We all agree that she just couldn’t take it, she couldn’t handle it,” Shurney said.

L.A. County Fire Chief Anthony Marrone and Supervisor Kathryn Barger, who represents Altadena, have called the delayed evacuation warnings concerning.

“I view this as my biggest challenge, trying to figure out what happened with late notifications at the Eaton fire,” Marrone said Friday. “I, too, want the answers and I want them sooner than later.”

Officials say evacuation alerts are typically issued jointly by fire officials, the sheriff’s department and the county Office of Emergency Management. Marrone said previously that if there was a failure by the fire department, he would “own it.”

Marrone did, however, reiterate that this was an unprecedented fire siege, fueled by hurricane-force winds and a bone-dry landscape, which sparked several fires simultaneously across the county.

“There’s never enough resources when you have a community conflagration,” Marrone said. “We were focusing on life protection.”

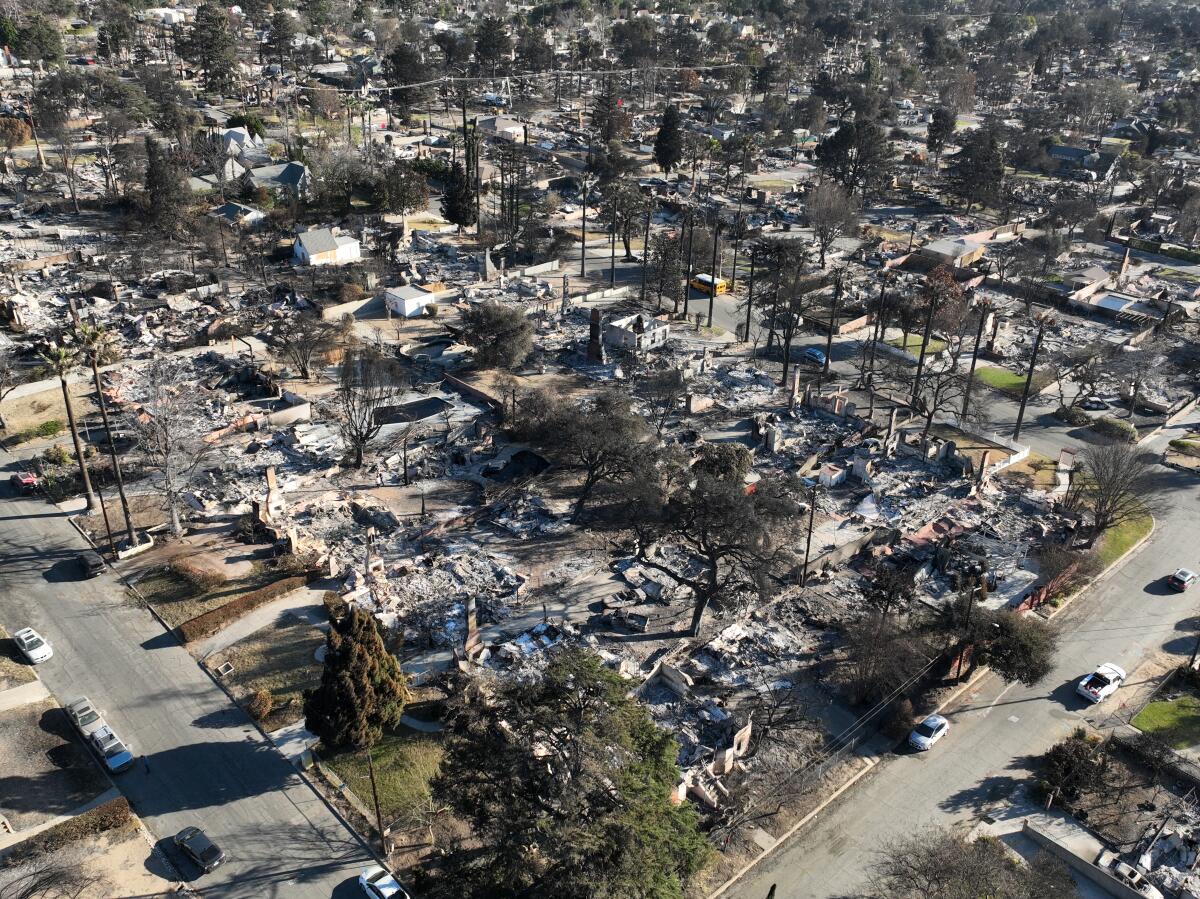

The Altadena fire wiped out much of a historic Black enclave in this picturesque town in the San Gabriel Valley.

Not far from Shurney’s and Cabrera’s homes, Lea Rogers’ family called the nearby sheriff’s station around 11 p.m. seeking information. They were told that they were still considered on level one, meaning there was no official warning or order for them to evacuate. However, they should be ready if such an alert comes.

The deputies assured the family that authorities would let them know if anything changed and that officials would be driving around on the intercom to make sure people got out, said Rogers’ son, Micah Coleman.

But around 3:30 a.m., Coleman’s girlfriend called to say fire was just three blocks away from their home on Highview Avenue and that they needed to evacuate.

When Rogers went outside to investigate, she said she could see the blazing, orange glow of the fire. It looked like thunder rolling at her, she recalled. Still, the family debated over whether they should leave, and decided to call the sheriff’s station again just after 4 a.m.

Rogers’ daughter, Nailah Tatum, said they were told there still wasn’t an emergency evacuation placed in their area. If they felt unsafe, however, they could evacuate, Tatum recalled being told.

As the Eaton fire spread, many areas were notified of evacuation warnings and orders well in advance. In the heart of Altadena, where all 17 reported deaths occurred, evacuation orders came hours after fire did.

Reassured by that call, Tatum said, she and her brother thought they were fine and wanted to stay.

But after looking outside again, the family decided to leave. They ended up evacuating around 4:30 a.m. — despite no official warning — but as they did, Tatum said they finally heard a sheriff’s deputy driving past their street heading east on Mariposa saying: “Evacuation, fire.”

“You couldn’t hear that crap,” Tatum, 31, said. “If you didn’t have your window down, you couldn’t hear that crap.”

They ended up losing everything, but are glad they didn’t wait to leave.

Adrienne Lett had gone to bed around 10 p.m., but was awakened by a banging noise sometime after 4 a.m. When she got out of bed, she recalled feeling dazed, not realizing that smoke had been creeping into the house.

Someone was banging on the family’s living room window. “Get out!” a man yelled. Strong winds were pushing embers down the street and smoke choked the air.

Lett woke up her 30-year-old daughter, and then called her brother, who lived nearby.

Lett guessed that the smoke had put her and her daughter “in a relaxed mode,” and said the man who banged on the window had saved their lives. “If he didn’t slam on that window loud enough, we would have never woke up.”

A video Lett shot at 4:54 a.m. showed a pitch black street. Trees catching fire. Embers whirling down the street and landing on their front lawn.

- Share via

Adrienne Lett was asleep in her Altadena home when she heard someone banging on her window in the predawn hours of January 8. She went outside to find embers raining down and someone she suspects is a fellow resident warning her to get out. She hadn’t received a notice to evacuate.

“Oh s—,” Lett said in the video, as a storm of embers rained down, burning her leg. The embers were so bad, she had to have her daughter drive her to her car, just a short distance away, she said.

Lett questioned why they weren’t alerted the same way an Amber alert goes out when a child has been abducted.

“I didn’t get no alert or text or anything,” she said. “We didn’t get any notice.”

The alert for their area wasn’t sent out until almost an hour later. Lett, who just turned 55 on Tuesday, thinks that would have been too late.

“We lost everything, we don’t have anything. We ran out with our pajamas on our bodies and house shoes and that’s all the belongings we have,” she said. “I’m thankful to have made it to my next birthday.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.