Column: Jimmy Carter was the right candidate for 1976, but was he the right president?

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Jimmy Carter was the right presidential candidate for his time in 1976 — a smiling, homespun, anti-Washington outsider promising truth and decency.

He was a natural populist, but he appealed to voters’ better angels, not their worst natures. He preached love, not hate.

That’s how I remember the former governor and peanut farmer from tiny Plains, Ga. I covered him up close, from his January campaigning in living rooms and on street corners in the Iowa caucuses through the July Democratic National Convention where he captured the party’s presidential nomination.

Jimmy Carter, the peanut farmer and little-known Georgia governor who became the 39th president of the United States, has died.

But he may not have been the right president for the time.

America was hit with astronomical inflation — up to 14% — that made what the country has gone through over the last two years seem like an economic boom. Mortgage interest rates neared 16% in some places.

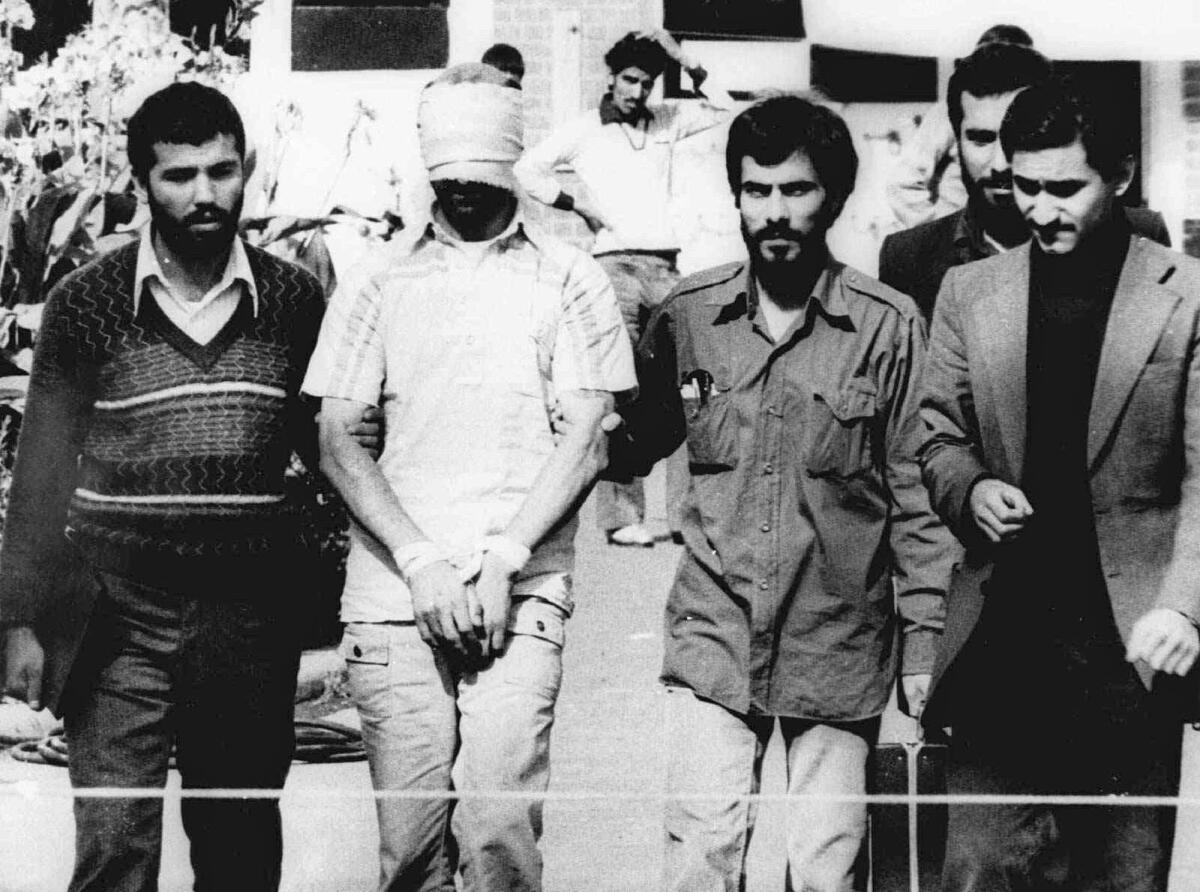

Moreover, his 1980 reelection prospects were doomed after Iranian revolutionaries seized 52 American hostages from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, and the Carter administration embarrassed itself with a failed rescue attempt.

The Democratic president came across to many voters as naive and over his head in sharp-elbows Washington. This despite his orchestrating a historic peace pact between the leaders of Israel and Egypt at Camp David.

Honors: His role in the 1978 Mideast accord and ongoing human rights work are recognized.

On the 1976 campaign trail, Carter’s stock speech included this solemn declaration: “I want a government as full of compassion and decency and openness and honesty and brotherhood and love as are the American people.”

In 1980, Republican candidate Ronald Reagan turned that against the incumbent and found a receptive audience: “Mr. Carter did not give us a government as good as the people. He gave us a government as good as Jimmy Carter. And we know that isn’t good enough.”

Reagan won in an electoral college landslide.

But Carter became arguably our greatest ex-president, with his humanitarian and diplomatic contributions.

Throughout life, he was highly energetic and tenacious — practically to the end.

I wrote a Carter obituary column nearly two years ago when he entered hospice care after deciding to forgo “additional medical intervention” for melanoma that had spread to his brain and liver. Then he held on until Sunday at age 100.

In 1976, Carter offered a fresh face and breath of clean air to cynical voters who had lost respect for the presidency over Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandals and lies told to them about the Vietnam War by Nixon and predecessor Lyndon Johnson.

“My name is Jimmy Carter, and I’m running for president,” the initially little-known candidate began each stump speech, always with a folksy grin. He was running against a crowded field of more established contenders, including eventually California Gov. Jerry Brown.

Carter was a terrific presidential candidate in 1976 — politically, the right person at the right time.

Carter would immediately follow with this: “My wife, Rosalynn, and I have been married 29½ years. She is the only woman I have ever” — pause — ”loved.”

Frankly, I thought this was a little weird — that the candidate felt it necessary to tell voters he had loved only one woman. But voters apparently ate it up. He won contest after contest and ultimately ousted incumbent Gerald Ford.

No rival could outcampaign him.

And he was always accessible to the news media, never afraid to banter with reporters. In the early days, he’d travel 100 miles to be interviewed by one small-town newspaper reporter.

One time I came across him standing alone on an Iowa street corner. “Stay here, George,” he told me. “I’m going to call a press conference.” He walked to a payphone, dialed an aide, and soon a few television and newspaper reporters showed up.

Later in the Illinois primary, Carter also showed that he could schmooze with powerful machine bosses, namely Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley. In Iowa and New Hampshire, Carter had attacked political pros. But in Chicago, he developed a strong alliance with boss Daley.

I vividly recall Carter, Daley and actor Mickey Rooney walking side by side leading Chicago’s lavish St. Patrick’s Day Parade the day after the Georgian won the Illinois primary to become the undisputed campaign front-runner.

But Carter never changed his rhetoric, always using plain talk and avoiding fancy words.

“What the voters are looking for,” he told a TV interviewer, “is someone who can run the government competently, who understands their problems and will tell the truth. We’re not dealing with ideologies this year.”

Another trademark line of his standard speech: “I will never mislead you. I will never tell you a lie.”

When Jimmy Carter was elected president, he offered a kind of balm for a country sickened by the Watergate scandal and disillusioned by the Vietnam War.

But truthfully, he confused many people with contradictions about where he stood on some issues, including abortion and busing to integrate public schools.

In Iowa after Carter won the caucuses, the state Democratic chairman, who was neutral in the race, was asked whether he thought voters misunderstood the candidate’s position on abortion.

“Misunderstood it, misunderstood it? Carter has three different positions on it,” the party leader replied.

Campaigning in the Wisconsin primary in Milwaukee one morning, I heard Carter espouse one position on school busing that seemed to please a predominately Black church congregation.

Then at noon, speaking to white voters at a bowling alley, he got nods of approval by asserting that busing should be voluntary and locally controlled.

Whatever. It worked politically.

Carter loved to show off his charming hometown of Plains, population 683. One unforgettable day, I covered him there.

Local folks had gathered around a loading dock to watch reporters sitting in swings and rockers while querying the future president. A freight train interrupted.

“We’ll have to wait until the train goes by,” Carter said. “It’s not a frequent occurrence. But it’s the custom in Plains to watch the train go by.”

Voters were attracted to Carter’s down-home style and grin back then. Would they be today?

Probably not, sadly. We’re too polarized and jaded half a century later.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.