To renovate an apartment — and not jack up the rent: These property owners have found a way

- Share via

To pay just $770 a month in rent, Mariana Puche Hernandez tolerated the mold growing in the bathroom of her studio apartment, even the sparks that flew when she plugged her phone into an outlet.

Then the 11-unit complex on Simmons Avenue in East L.A. went up for sale and became a prime target for investors looking to renovate apartments and hike the rent beyond what residents could afford.

“There was panic,” Puche Hernandez said.

Across the nation, the United States is losing thousands of homes affordable to low-income families as individual investors and large companies buy older apartment buildings to renovate and sharply raise rent. The investments have sparked concerns over gentrification, displacement and homelessness.

But affordable housing advocates say there doesn’t have to be a choice between renovation and affordable rent. A number of models exist to repair older properties and keep rents low — including nonprofit ownership and certain bond financing programs. They just need public subsidies and the political will to preserve them or get new ones off the ground.

“These units are important to save,” said Matt Alvarez-Nissen, a researcher with the nonprofit California Housing Partnership.

That’s because only 16% of low-income California tenants have a home where government policy limits rents based on income, according to the partnership. The rest, 2.9 million households, live in unsubsidized units subject to the whims of the private market. Rent control laws help some of those tenants from seeing enormous rent increases each year, but the laws don’t mandate affordability.

While most unsubsidized homes have rents that create financial burdens for low-income tenants, a significant number do not. In 2020, the partnership estimated nearly 1 million of those units had rents low enough to be deemed affordable because landlords set the price at that rate even though there was no government mandate to do so.

By last year, the partnership said the number of these “naturally occurring affordable” units had dropped to about 823,000.

The loss is in large part driven by a housing shortage that makes it an attractive investment to renovate old apartments for tenants who can pay more.

At times, properties are dated, but functional. Others need serious repairs.

Explore the latest prices for homes and rentals in and around Los Angeles.

In recent years, wealthy professionals such as doctors and lawyers invested in these renovation deals, handing their money over to private real estate firms to carry out the projects.

Bigger players are involved too.

A recent Times investigation found U.S. public pensions are investing billions of dollars into riskier real estate funds that acquire apartment buildings, renovate them and, on average, raise rent faster than other landlords in the surrounding community.

The money public pensions use to make their investments, including in high-risk real estate funds, comes from both worker and government contributions.

As a result, some taxpayer dollars contribute to raising rent, while other public funds flow to create low-rent units — mostly by building new, income-restricted homes.

According to the housing partnership, there’s no state fund in California dedicated solely to purchasing market rate homes and putting income restrictions on them, even though doing so is typically cheaper than building new ones.

State Sen. Anna Caballero (D-Salinas) tried to change that when last year she put forth a bill that would’ve created the Community Anti-Displacement and Preservation Program. She sought $500 million to fund the acquisition and rehabilitation of currently unrestricted units and put affordability restrictions on them.

In pitching the bill, Caballero described it as a “fast and cost-effective way to increase the supply of affordable homes in California.” In an interview, she said the bill died this year because there wasn’t money available, in part because of Sacramento’s budget shortfall.

“We just have to identify where the money would come from,” Caballero said. “I am not done with it.”

Caballero said she doesn’t support the state Legislature dictating the investments public pensions can make, but she said retirement systems should have discussion internally whether they should invest in such higher-risk funds.

“We have a priority to house people in California and we may be working at cross purposes,” she said, referring to public money going toward both raising the rent and lowering it.

On Simmons Avenue in East Los Angeles, tenants got lucky.

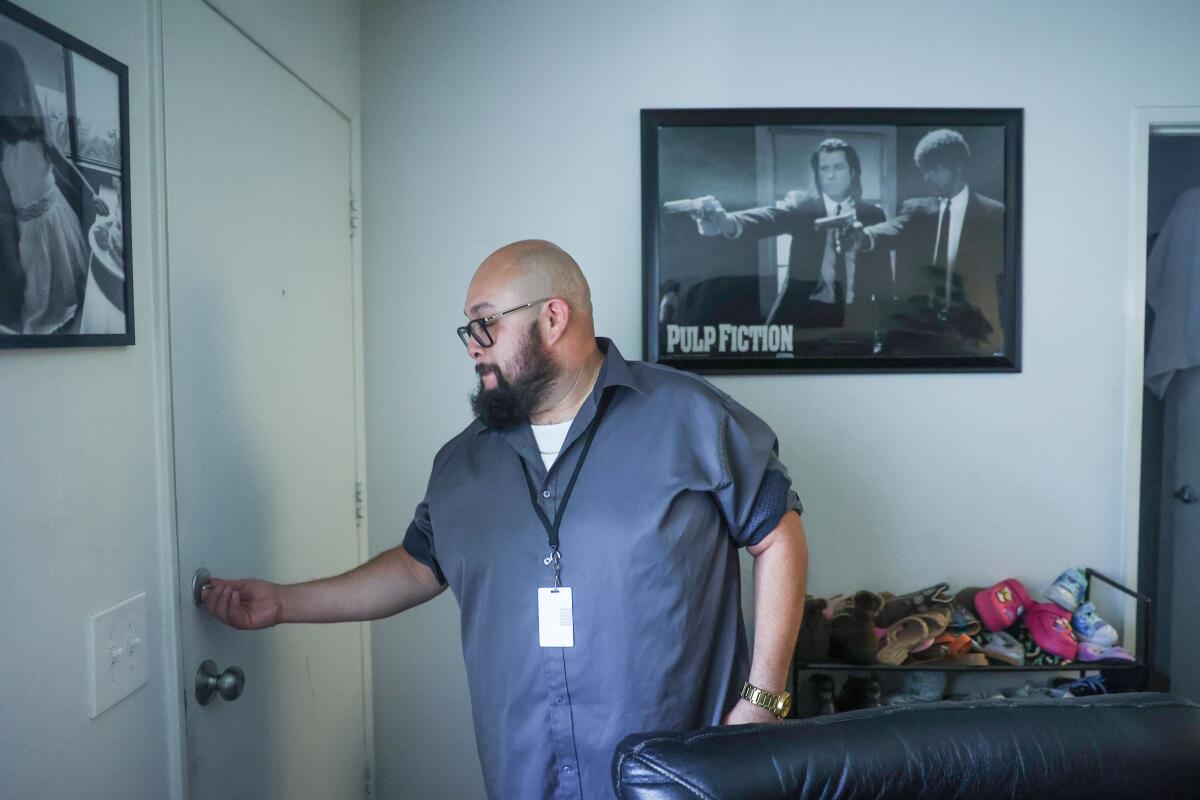

Rather than private investors, the property sold to a nonprofit partnership that put Puche Hernandez and other residents in temporary housing. The new owners then repaired units and fixed the electrical, plumbing and foundation problems that plagued the entire property.

Tenants moved back in. Rents stayed the same.

Finding the funding to accomplish such projects can be a challenge.

The new owners, the nonprofit Little Tokyo Service Center Community Development Corp. and community land trust Fideicomiso Comunitario Tierra Libre, turned to a county pilot program that sought to support the community land trust model.

In the model, community organizations acquire land to keep it off the private market, then rent or sell the units on site at affordable prices.

If residents purchase a unit, the land typically stays with the trust. While new homeowners can build some equity, they face limits on how much they can resell their unit for, in order to keep the home affordable for the next owner.

The $14-million pilot program funded the acquisition of eight properties by five different community land trusts. There’s no money left for additional acquisitions, but Supervisor Hilda Solis, who proposed the pilot, said she wants to make it permanent in the future.

One dedicated funding source for such efforts will soon be available in the city of Los Angeles through Measure ULA, often referred to as the mansion tax.

The measure requires a percentage of ULA revenue be used to fund a program to acquire unsubsidized units, rehab them and place affordability restrictions on them.

Over the next few years, the city estimates roughly $15 million will be available annually for that effort, which would grow substantially if total ULA revenue climbs as much as backers hope.

Other options exist as well.

In 2021, using a bond financing program, the California Statewide Communities Development Authority, or CSCDA, purchased a 1980s apartment complex in Pomona and partnered with a real estate firm to manage the deal.

Before the acquisition, 302 of the property’s 472 units were reserved for very low- to moderate-income households, but those restrictions were set to expire.

Tenants at the property said gym equipment was often broken; paint on the buildings was fading; and strangers freely entered the complex, at times stealing packages.

Since then, the development authority and its private partner Waterford Property Co. of Newport Beach have spent millions. They repainted the buildings, installed new workout equipment, hired security guards and built a parcel locker for packages.

The property, known as the Sienna Residences, also received a new hot water system, which the owners expect will save tenants in utility costs. New rent restrictions were placed on all units.

“I am pretty comfortable,” said Bradley Rosales Garcia, who lives in a one-bedroom with his 4-year-old daughter and thanks to the rent subsidy has the ability to show her California. “Two weeks ago we went to June Lake. On her birthday, I was able to take her down to Legoland.”

According to a Times analysis of bond documents, average rent at the property has risen just 0.6% in the two-plus years since the sale. Nearly half the units saw rent decline over that time.

According to Waterford, rent can be kept low because the development authority owns the property and, as a government agency, doesn’t pay property tax. The money to acquire and rehab the Sienna Residences came from bonds the agency sold to institutional investors, providing an opportunity for public pensions if they wish.

“If you invest in projects like this, maybe they are earning a little less of a return, but they aren’t raising rents on teachers,” said John Drachman, co-founder of Waterford.

The Newport Beach firm has partnered with CSCDA on 14 other deals to buy buildings and lower the rent. Those properties, however, were all newer, luxury buildings. Rent was reduced, but remained higher than older properties nearby.

Sean Rawson, Waterford’s other co-founder, said the company didn’t want to acquire an older property in the program until it better understood how to budget for repairs that such buildings would need, but so far Rawson said Sienna Residences is working out as planned for bond investors.

A dispute with some local tax assessors has put new projects on hold for now, Rawson said, but Waterford wants to work with CSCDA to purchase more older properties, including those that don’t have income restrictions, but would after they were acquired.

“This is scalable,” Rawson said. He estimated there could eventually be $2 billion to $3 billion annually invested in such deals for older buildings in California. “We know there will be appetite from bond investors.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.