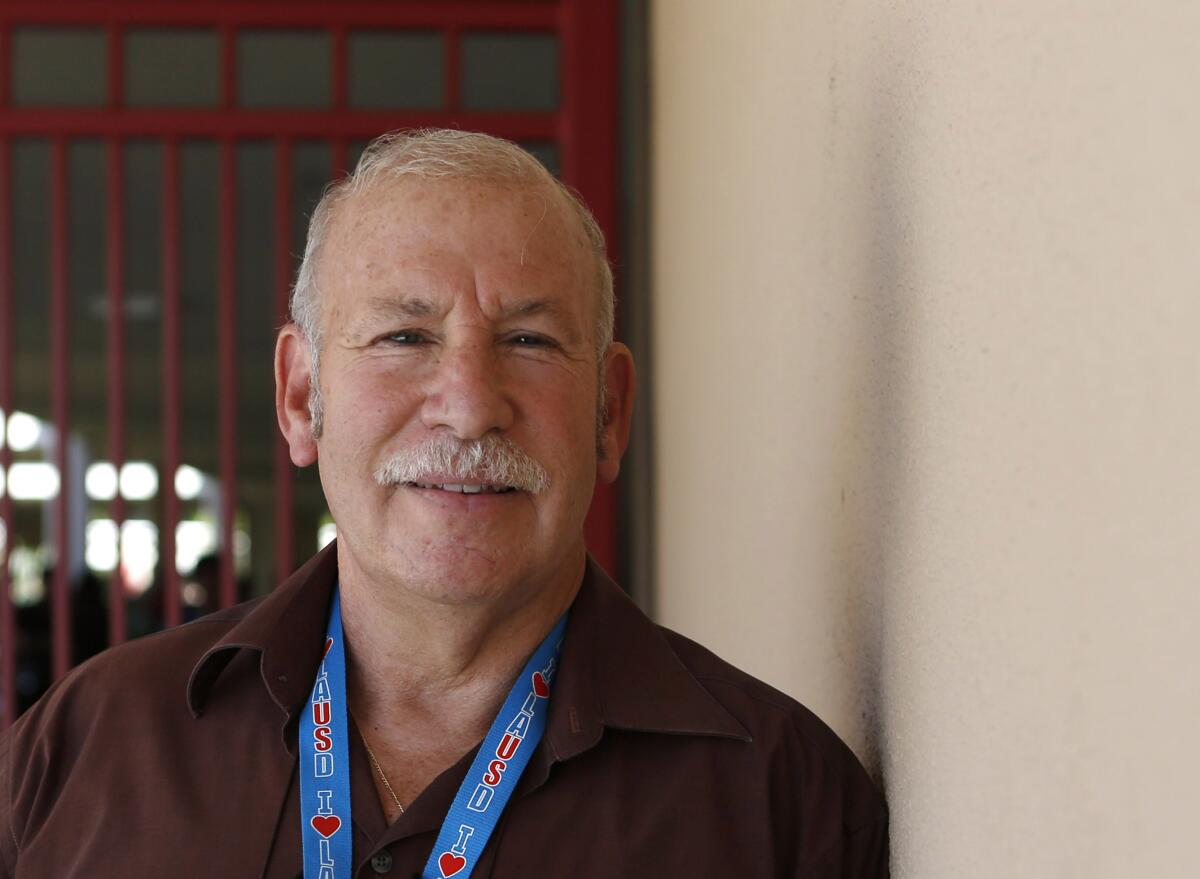

The campaign spending in District 3 is partly a throwback to the last 20 years or so in which the same two big-spending camps opposed each other time after time: the teachers union and supporters of charter schools.

An independent campaign in support of Schmerelson — funded by United Teachers Los Angeles — spent $785,000 in the primary. In the general election cycle the teachers union has spent more than $355,000 through Oct. 2.

A larger amount of money is flowing into an independent campaign on behalf of Chang — $870,000 in the primary followed by more than $2.48 million through in the general election.

While the two candidates benefited from a similar level of outside spending in the primary, for the general election, so far, Chang’s advantage is 7 to 1.

Chang’s major funder is Bill Bloomfield, a retired L.A. businessman who has moved out of state. He does not consider himself a die-hard charter school supporter, but he is aligned in this election with the political arm of the California Charter Schools Assn.

Bloomfield has become, in recent elections, the major nonunion funding source standing in opposition to the teachers union.

Schmerelson has not been aggressively anti-charter, but has been part of a board majority that has placed new limits on when charters can have access to space on a district-owned campus.

The distinctions between Schmerelson and Chang have been enough to trigger a charter-versus-union proxy war of sorts, with both sides concluding that the direction of the district related to charters is at stake.

Chang has tried to link Schmerelson to issues that he has alleged amount to wrongdoing.

One episode involved Chang’s allegation that in 2023, at Madison Middle School, where he is a math teacher, eighth-graders did not come to school on the last day of the school year in June, but were falsely recorded as present in class.

Chang raised his concerns, he said, with his principal and other district officials. He also said he refused to record his absent eighth-graders as present and later discovered that someone had altered his class attendance records — to mark all students as present on that day — without his permission.

Attendance is a major factor in the level of funding that schools receive.

The district eventually said Chang was right and the inaccurate attendance data amounted to $600 in extra state funds the district should not have received. Estimates from others were much higher, according to an April story published by KCBS.

Chang alleges that colleagues have told him that such practices have occurred at other schools as well. District officials said only Madison was affected.

Madison Middle School, located in Valley Glen, is not within Schmerelson’s district. However, Chang said Schmerelson bore responsibility because “Schmerelson neglects the basic duties of oversight as an elected school board member.”

In an interview, Schmerelson responded that keeping accurate attendance is legally and ethically mandatory and also vital for tracking the safety and learning of students. He said the district took disciplinary action — the details are confidential — in response to what Chang reported at Madison.

More recently, environmental activists have alleged that the school district is slipping in its commitment to avoid the use of potentially dangerous pesticides on campus, for such purposes as landscaping. Chang holds Schmerelson responsible on this matter as well.

In an interview, Schmerelson said the truth is essentially the opposite, that he volunteered to lead a committee to make sure that the district is limiting and safely managing the use of pesticides.

In a brief response, a district spokesperson said in a statement that L.A. Unified “has a longstanding process regarding the handling of harmful chemicals. These procedures are continuously assessed to maintain the safest protocol.”

Other issues to arise in this contest have included the role of school police on campus and allegations that the district misspent voter-approved funding to increase arts instruction, questions that the candidates have addressed below.

The responses to specific issues were compiled through a questionnaire sent to candidates by The Times, follow-up emails and conversations with the candidates. The content was supplemented with material from campaign websites and from statements at public campaign forums. Candidates also had the opportunity to provide updated input after the primary.

The answers are summarized or lightly edited for length or clarity.