- Share via

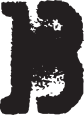

Bill Harris, a postal worker and Marxist whose face would soon be on FBI Wanted posters from coast to coast, opened his local newspaper in late 1973 and became intrigued by an item from high society.

Patricia Hearst, the 19-year-old heiress of a storied journalism empire, was engaged to be married. The article identified her as an art history student at UC Berkeley.

Harris sensed an opportunity. He walked onto campus and found a ledger book in which Hearst had written her address.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

“Who would have thunk it would be so simple? It was a fluke,” Harris, now 79, told The Times in a recent interview. “I looked in the book and thought, ‘I wonder.’”

The Symbionese Liberation Army — the tiny cadre of Bay Area radicals that Harris belonged to — learned that Hearst lived without security at that address near campus. Harris and two confederates armed themselves and stormed her apartment on Feb. 4, 1974. They beat her hapless fiance, and Harris carried a bound, gagged and blindfolded Hearst to the trunk of a stolen Chevy Impala.

Hearst was confined to a closet for weeks, blindfolded and carried between hideouts in a garbage can.

Harris would spend a year and a half on the run, slipping between safehouses with the heiress, who infamously picked up a machine gun herself, denounced her parents as pigs and pledged her allegiance to the group that had abducted her.

The SLA’s symbol was the seven-headed cobra, its motto, “Death to the fascist insect that preys upon the life of the people.” They were mostly white and college-educated, with middle class backgrounds.

Hearst’s transformation into a fervent member — a psychological puzzle that has never yielded tidy answers — was part of a strange saga at the nexus of leftist militancy and American aristocracy, saturation media coverage and youth revolt. For anxious parents who worried that Vietnam-era counterculture might swallow their children, the heiress with the M1 seemed the nightmare embodiment of how far rebellion might go.

The SLA claimed credit for the kidnapping, and demanded that the Hearst family feed the poor en masse. Hearst’s desperate father, publisher of the San Francisco Examiner, spent $2 million on a food giveaway, and crowds rioted as food was flung from trucks. A disapproving Gov. Ronald Reagan wished aloud for an outbreak of botulism.

The group took inspiration from the Tupamaros, Uruguayan Marxists who staged attention-grabbing kidnappings. A goal, Harris said, was to trade Hearst for two associates who had been arrested for the recent killing of the Oakland school superintendent. This part of the plan went nowhere.

The SLA did not envision keeping Hearst, Harris said, and he was against it.

“She was gonna go home and explain her captivity in the People’s Prisons we set up for her,” said Harris, a Vietnam veteran with an undergraduate degree in theater and a masters in urban education from Indiana University. “That would have been good propaganda. That’s what I thought it should be.”

But Hearst was coming to identify with her captors and was upset that her mother had accepted Reagan’s offer to reappoint her to the UC Board of Regents.

“She hated her mother,” Harris said. “She didn’t want to go home.”

Her deeper motives were hard to fathom.

“I thought, ‘Why would you want to go from being an heiress to being targeted for assassination by the government?’” Harris said. “I spent hours trying to convince her that staying with us was a bad idea.”

The SLA soon grasped the potential for a publicity bonanza, and on April 15, Patricia Hearst, now calling herself “Tania,” emerged into public view a totally transformed person. With its flair for guerrilla theater, the SLA picked the Hibernia Bank to rob, knowing that security cameras would capture Hearst storming the lobby with a military-style M1 carbine, under no apparent coercion.

She released a tape justifying the “expropriation” of $10,660.02 from the bank and describing herself as “a good soldier in the people’s army.” She signed off, “Patria o muerte! Venceremos!” (“Fatherland or death! We will win!”)

Her loyalty to her comrades was underscored a month later, when a clerk at Mel’s Sporting Goods in Inglewood suspected Harris of shoplifting and tried to slap handcuffs on him.

As they struggled on the street, Hearst — waiting in a van nearby — sprayed the storefront with gunfire, allowing Harris and his wife, Emily, to scramble away.

“I figured she’d be smart and head on back to the safehouse,” Harris said. “She picked up my machine gun, and she fired a burst of about 10 rounds, and some of the bullets hit about two feet from my face.”

The next day, the three fugitives were hiding out at a motel near Disneyland when the LAPD caught up to the rest of the SLA, who were hunkered down in a yellow house on East 54th Street in South Los Angeles. A gun battle raged on live television, the LAPD launched tear gas, and the house went up in flames. Six SLA members were killed, including leader Donald DeFreeze.

Harris remembers watching the conflagration from the Anaheim hotel room. He has no doubt that he and Hearst would have died if they had been with the others that day.

“We all made choices to do something that we knew full well was likely to get us killed,” he said, so the violence “was not a big-ass surprise.”

The SLA essentially ended that day, Harris said, though its remnant survivors remained on the run and desperate for cash. In April 1975, they participated in the robbery of a bank in Carmichael, a Sacramento suburb. Myrna Opsahl, a 42-year-old mother of four, was killed by a shotgun blast.

“I feel horrible about what happened to Myrna Opsahl,” Harris said. “That’s what bothers me most. There’s horrible collateral damage when you embrace tactics like that.”

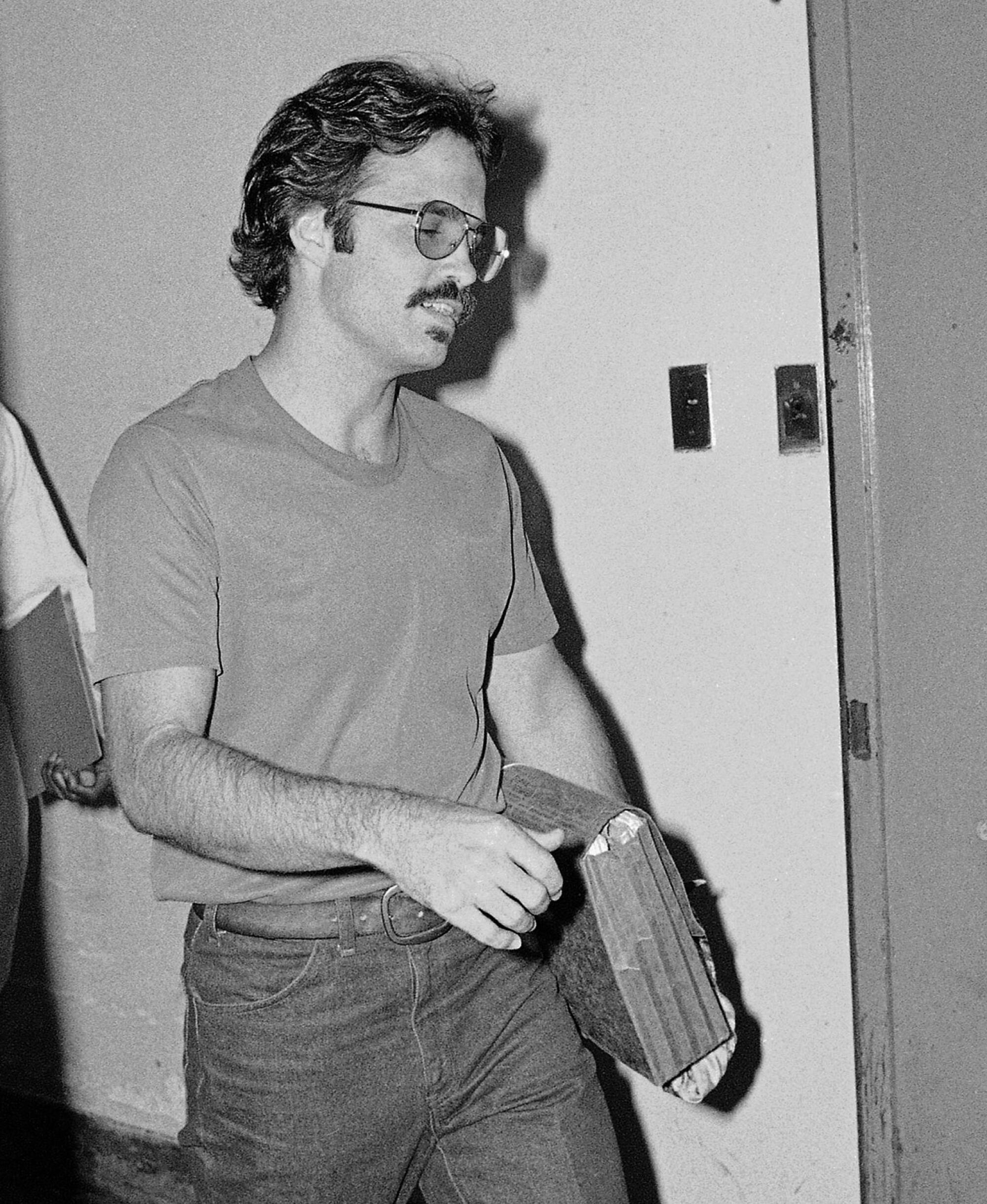

When the FBI caught Hearst in September 1975, she clung to her revolutionary persona at first, describing her occupation as “urban guerrilla.”

As she faced federal charges for the Hibernia bank robbery, however, the Tania persona vanished. Her defense was that she had been brainwashed by the SLA, a victim of “coercive persuasion.” She said she had been raped by SLA members Willie Wolfe and DeFreeze, a claim Harris would always vehemently deny and the government challenged.

A prosecution psychiatrist portrayed her as a bored, amoral rich kid who lacked a sense of meaning and found a warped sense of liberation as an SLA soldier.

Hearst took the Fifth 42 times to avoid questions about her “lost year,” 1975, which included the Carmichael robbery. The jury convicted her. She got seven years but served only two, her sentence commuted by President Carter after intense lobbying from the Hearsts.

“She was more unpopular than the Boston Strangler,” her attorney, F. Lee Bailey, would say ruefully.

Hearst, who is now 70 and could not be reached for comment, soon afterward married her bodyguard, started a family and wrote a memoir, “Every Secret Thing.” She got roles in John Waters movies and raised prize-winning French bulldogs.

For his crimes, Harris served about eight years. He remarried, raised two boys and coached youth soccer. He worked as a private investigator for defense attorneys in the Bay Area.

“People talked to me who wouldn’t talk to cops,” said Harris. “I had huge street cred.”

He is now retired and living in San Francisco, where, he said, “you can be an ex-terrorist and be rehabilitated, and be appreciated, because s— like that happens here.”

Nick Kazan wrote the 1988 movie adaptation of Hearst’s memoir, starring Natasha Richardson. Her performance accommodated arguments that Hearst was both willful rebel and mental captive.

“People always look for the simple explanation. They look for, ‘She was brainwashed’ or ‘She was a willing participant,’ as if it’s either/or,” Kazan said.

The character’s transformation into Tania suggests a desperate assertion of autonomy from a young woman who has been stripped of it. Kazan imagined her thinking, “I’m here in this closet and you have kidnapped me and you think you can control me, but actually, I am the master of my own fate.”

Hearst was under tremendous psychological pressure, he added, and her motives might be mysterious even to her.

“There’s no way to know what was going on,” he said. “I don’t think human beings completely know why they do what they do. They just do it.”

Jon Opsahl, who was 15 when his mother was slain in the Carmichael robbery, has had half a century to think about Hearst.

He has concluded that she is “probably as much a victim of the SLA as I am.”

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact [email protected]

“She suffered big-time in the kidnapping, and the brutality and the rapes,” said Opsahl, a retired doctor. “That must have gone on for weeks, long enough to affect a young, naive, overly sheltered 19-year-old out of Berkeley.”

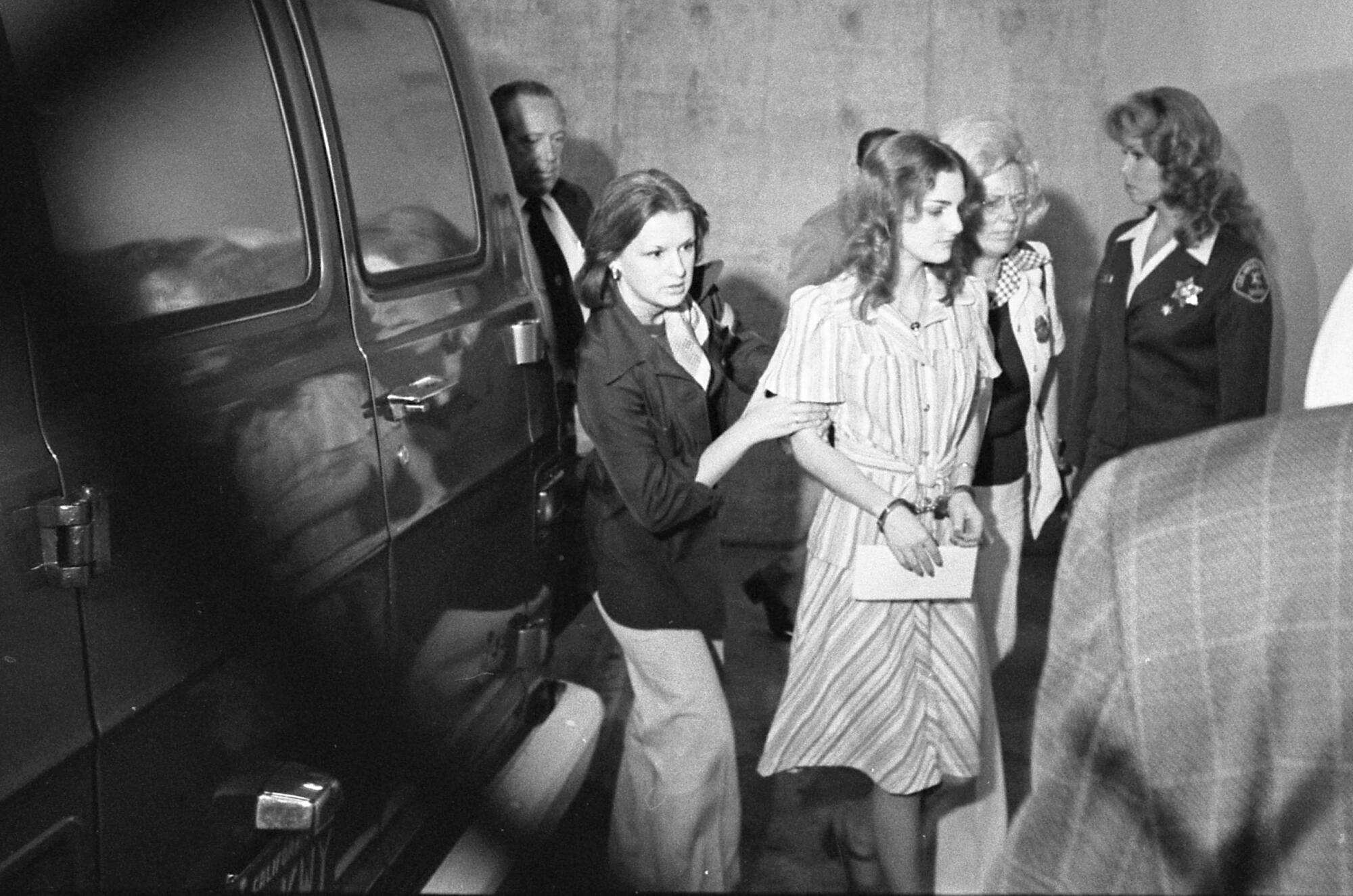

Opsahl pushed hard to bring charges against the former SLA members responsible for his mother’s death. Hearst admitted that she was one of the getaway drivers. According to Hearst’s memoir, Emily Harris fired the gun that killed Myrna Opsahl and derided her as a “bourgeois pig.”

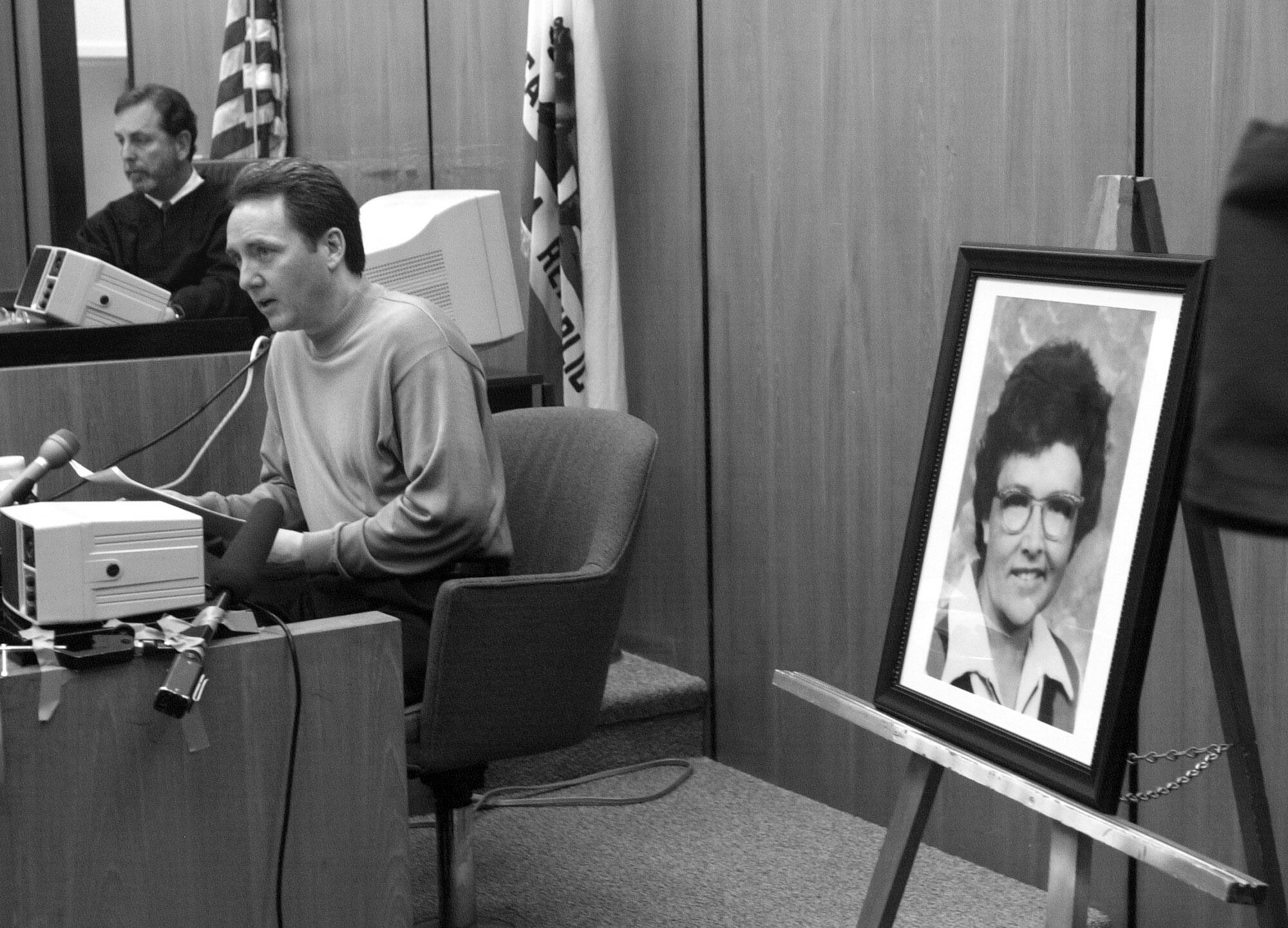

Even so, Sacramento prosecutors did not file a case against Bill Harris, Emily Harris and three other SLA members until the early 2000s. Hearst was promised immunity if she testified, and the evidence was ample, but the defendants cut deals for relatively light time.

Bill Harris, who admitted to being a getaway driver, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and served nearly four years. He believes prosecutors did not insist on a trial because Hearst would have had to take the stand. He said he was prepared to act as his own lawyer so he could cross-examine her in minute detail. Questions would include the activities of her “lost year.”

“What the Hearsts wanted to do more than anything is preserve the narrative that she didn’t do any of this on her own free will,” Harris said. “It would be me taking her through every day that she spent with us for 19 months. I knew they would find some way to make us an offer we couldn’t refuse.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.