Times reporter was leaked list of problem deputies. The Sheriff’s Department investigated her

- Share via

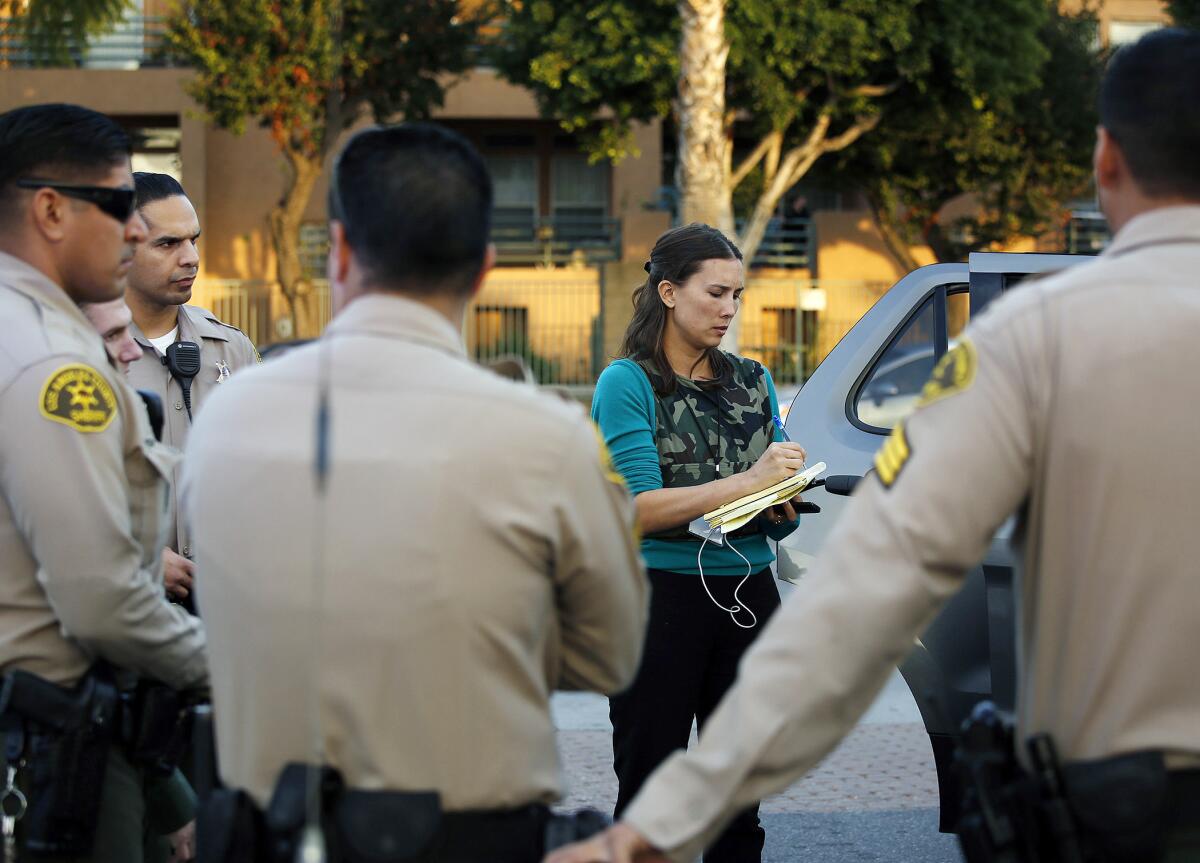

For at least three years, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department secretly investigated — and ultimately urged the state attorney general to prosecute — a Los Angeles Times reporter who wrote about a leaked list of problem deputies, according to internal department records.

The inquiry began in 2017 when investigators under then-Sheriff Jim McDonnell tried to figure out who slipped the list of roughly 300 names to reporter Maya Lau. The case soon fizzled out. But after Alex Villanueva took office as sheriff in 2018, the department revived it, according to a 300-page investigative case file recently reviewed by The Times.

The department eventually deemed Lau a criminal suspect — alleging she knowingly received “stolen property.” And it pointed to Diana Teran, its own constitutional policing advisor, as the source of the leak, even though Teran was the one who’d initially reported it and denied passing along the information.

Sheriff’s officials sent the case to Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta in 2021, and in May of this year his office formally declined to prosecute. The office declined to answer specific questions, saying only that it “found insufficient evidence” to merit criminal charges.

“I’m glad this investigation is over, and it’s an outrage that the Sheriff’s Department would criminally investigate me as a reporter for doing my job,” Lau, who left the paper in 2021, told The Times. “It’s the kind of action that’s aimed at intimidating journalists from digging into government agencies.”

A look inside former Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s multi-year investigation shows investigators relentlessly pursued a probe focused on supposedly stolen records and document leaks.

The Sheriff’s Department confirmed its investigation into Lau is closed and said it is no longer surveilling reporters.

“Under the leadership of Sheriff [Robert] Luna, we do not monitor journalists and we respect the freedom of the press,” the department wrote this week in an emailed statement.

In an email Thursday, Villanueva did not address specific questions about the investigation into Lau. Instead, he accused another reporter of a crime and said lawyers for the county had been “trying to obstruct the case at every step.”

Journalists generally cannot be held liable for reporting on leaked documents that involve matters of public concern, even if the reporter knew that the materials were obtained illegally.

“You’re not authorized to break into a file cabinet to get records. You’re not authorized to hack computers. But receiving information that somebody else obtained unlawfully is not a crime,” said attorney David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, which advocates for free speech and government transparency. “Publishing that information is protected under the 1st Amendment.”

::

The leaked records at the center of the investigation date to 2014, when Teran — who was working at the Office of Independent Review, a civilian oversight group hired by the county — had begun collecting names for a so-called Brady List of officers with problematic disciplinary histories. The name refers to a landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Brady vs. Maryland, that requires prosecutors to turn over any evidence favorable to a defendant, including evidence of police misconduct.

To make her list, Teran relied on information from the district attorney’s office and from Sheriff’s Department databases, according to what she told investigators in 2017 and 2018 as part of the administrative inquiry. She stopped adding new names in late 2014, because she believed the Sheriff’s Department had started keeping its own official Brady List by that point.

Then in 2015, she started working for the Sheriff’s Department as a constitutional policing advisor, a position created by McDonnell to act as an internal watchdog.

Two years later, the LASD investigative file says, she heard that Lau and other Times reporters had begun asking certain deputies how they felt about being on the Brady List. To figure out what list the reporters had and where they’d gotten it, Teran tracked down any recent public records requests from The Times.

She found out reporters had asked the district attorney’s office for information about roughly 300 deputies — the same deputies named on her list from 2014. When she reviewed the names, Teran noticed the reporters’ list even featured the same errors as hers, down to the typo on one employee identification number. At that point, the report said, Teran “became concerned that ‘her Brady list’ was leaked to the media” and began trying to figure out who could have leaked it.

The report says there was one high-ranking official in particular she began looking into by asking the department’s Data System Bureau what copy machine he had access to and whether there was a way to examine its hard drive. According to the case file, however, the drive “had been destroyed and there was no remedy for Teran to seek in trying to exonerate herself.”

Three days later, on Dec. 8, 2017, The Times published its story detailing some of the misconduct and criminal convictions that had landed deputies on the list. One deputy planted evidence, The Times reported. Another pulled over a stranger and received oral sex from her in his patrol car. A third pepper-sprayed an elderly man in the face and then wrote a false report to justify arresting him. (The Times series highlighted the secrecy of police misconduct records, and a year later, the California Legislature approved landmark measures that provided dramatically greater public access to internal investigations of police shootings statewide.)

A week after the story ran, internal affairs investigators interviewed Teran. According to the investigative case file, Teran told them the names of several high-ranking officials she thought may have gotten a copy of her list, including the interim sheriff and several chiefs and commanders. They all denied keeping copies or leaking them to Lau, according to the report.

At some point before McDonnell left office in 2018, investigators dropped the inquiry, marking it “unresolved and inactivated” instead of turning it into a formal criminal investigation.

Several months into the Villanueva administration, Det. Mark Lillienfeld was assigned to investigate a related case involving allegations that Teran and other oversight officials had illegally accessed deputy personnel records, including some the department had voluntarily turned over to them months earlier. That inquiry by Lillienfeld — a key investigator on Villanueva’s controversial public corruption unit — reopened the dormant Brady List probe.

The 80-page report Lillienfeld ultimately produced, part of the more than 300-page investigative case file reviewed by The Times, is at times difficult to follow. The writing is punctuated by testy asides and innuendos about Villanueva foes, whom the report accuses of engaging in extramarital affairs, ethical violations and new crimes, among other things.

Amid the long and often scrambled narrative, the report describes two possible instances in which Teran could have leaked the list. The first was in May 2017, when Lau sat down with Teran and Mark Smith — the department’s other constitutional policing advisor — to ask a series of questions about Brady policies and the handling of Brady material.

The report states that Teran denied having a paper or digital copy of the list with her that day. The report calls her denial of leaking the records “a lie” and said it was “deceptive” for Teran to say she didn’t have the list with her based on the assumption that she would have had her computer with her in her office, where the interview took place. The computer, the report says, would have contained a copy of the list.

But according to a transcript of her September 2018 interview with investigators, Teran was never asked whether she had a digital copy. She was only asked whether she had a copy in her purse, briefcase or “anything like that.”

A little-known team of investigators in the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department has pursued criminal investigations into some of Villanueva’s most vocal critics.

After alleging Teran leaked the Brady List in May 2017, the investigative file suggests she could have also leaked it more than a year later.

Shortly after McDonnell lost his bid for reelection in November 2018, Lau emailed the Sheriff’s Department to ask for a phone interview with Teran, according to the report.

“We’re doing a story today on what Villanueva will mean to reforms,” Lau wrote. “Given that he’s said he would eliminate the (constitutional policing advisors), I think it would be great to hear from Diana on what the CPAs actually accomplished.”

The two talked on the phone a few hours later, and Lau quoted Teran in an article published the following morning on Nov. 28, 2018.

Later that week, Lau put in another records request — something reporters do on a regular basis — for information about 322 department employees, including the incoming sheriff. The request was sent weeks before a new law was set to take effect broadening public access to police disciplinary records, but Lillienfeld’s report focused on the proximity to Lau’s interview with Teran.

“It defies explanation or logic to think that Lau was able to obtain a list of over 300 LASD personnel within just three days after meeting with Teran, from any source other than Teran,” Lillienfeld wrote.

When internal affairs interviewed Teran in 2018, she said she wasn’t the source of the leak.

“I just want to make it abundantly clear that I did not provide Maya Lau a copy of this list or any other list that we have referred to … either at that meeting or any other meeting or any subsequent meeting, ... nor did I talk to her on the phone and read her the list, nor did I give or direct anybody else to provide her with that information,” she told investigators under oath. “I just want to make it abundantly clear that it wasn’t just on that date, but on any date and of that, I am 100% positive.”

A little over two years after Lillienfeld began his investigation, in fall 2021, Undersheriff Tim Murakami sent the 300-page case file — which included the inquiries into both the Brady list leak and the accessing of personnel records — to Bonta. The file identified Lau as a suspect along with Teran, Teran’s assistant, Inspector General Max Huntsman and an attorney for Huntsman’s office.

Ultimately, Bonta’s office declined to prosecute the case, notifying the Sheriff’s Department — but not the five people identified as suspects, including Lau — of that decision in May. Around the same time, though, Bonta announced 11 felony charges against Teran in a similar case that his office says stemmed from an unrelated investigation.

::

The years-long attempt to prosecute Lau is not the only time the Sheriff’s Department has targeted a reporter in recent years. In 2020, LAist reporter Josie Huang was slammed to the ground and arrested by sheriff’s deputies while covering a protest. Her press ID was visible on a lanyard around her neck. Villanueva defended his deputies’ handling of the incident and referred the case to the district attorney’s office so Huang could be prosecuted. Prosecutors declined to take up the case, and Huang sued, settling with the county last year for $700,000.

Two years after Huang’s arrest, Villanueva targeted another Times journalist in a criminal leak investigation for her reporting on a departmental cover-up. After announcing the inquiry at a public news conference, he backed off under a barrage of criticism and denied that he considered the reporter a suspect.

Both of those cases received widespread media coverage, and this week independent journalist Cerise Castle reported on department records showing that sheriff’s officials had been keeping an eye on her as far back as 2021.

Sheriff Villanueva announces criminal investigation of Times journalist who revealed an incident in which a deputy kneeled on the head of an inmate.

But until now the department’s investigation into Lau flew under the radar.

Snyder, the First Amendment Coalition executive director, raised concerns about how far the investigation into Lau may have gone. The case file does not mention any efforts to surveil Lau or monitor her phone, and Lillienfeld did not respond to a request for comment. It’s also unclear what state prosecutors did after agreeing to take over the case.

“If you as a reporter believe your work could subject you to criminal investigation, that’s a chilling effect,” Snyder said. “That’s not good for journalism, it’s not good for democracy, and that’s the reason these investigations shouldn’t happen — can’t happen — under the law.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.