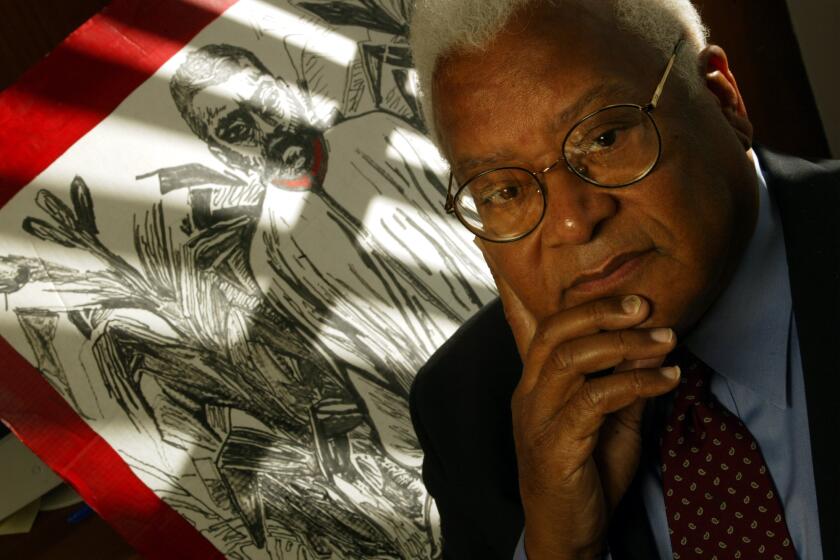

James Lawson’s booming voice and loving spirit left a lasting mark on this UCLA professor

- Share via

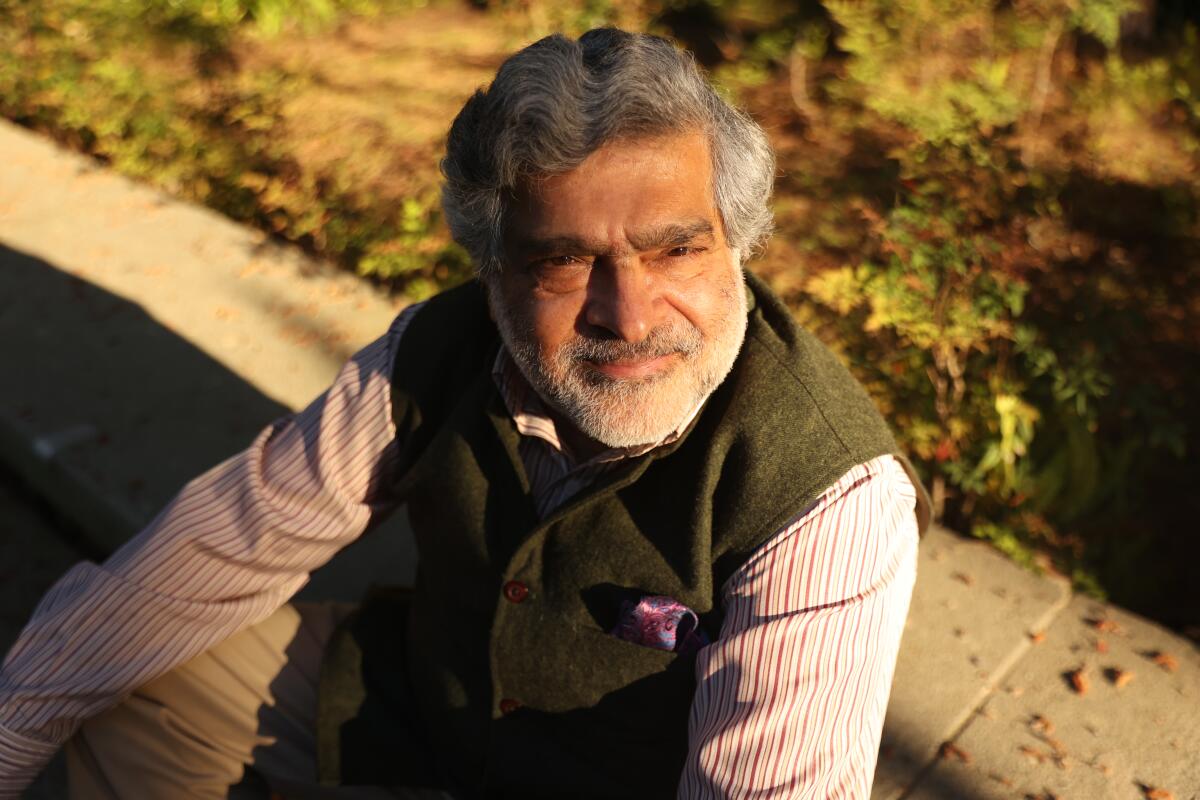

UCLA historian Vinay Lal remembers speaking alongside the Rev. James Lawson during a panel discussion in Pasadena in 2008 and feeling awestruck by the “majestic” manner in which the veteran civil rights leader spoke about the power of nonviolence and its ability to change the course of history.

“He had a booming voice, very confident, but the amazing thing was that that confidence always came with compassion at the same time,” said Lal. “The way in which he spoke of nonviolence, it was coming out of a depth of experience.”

Lawson’s commanding presence, moral clarity and big heart were all on Lal’s mind this week as he contemplated the storied life and contributions of his friend, who died in Los Angeles on Sunday after a brief illness. Lawson was 95.

Lawson was recruited by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Lawson spent decades in Los Angeles working as a pastor, labor movement organizer and professor.

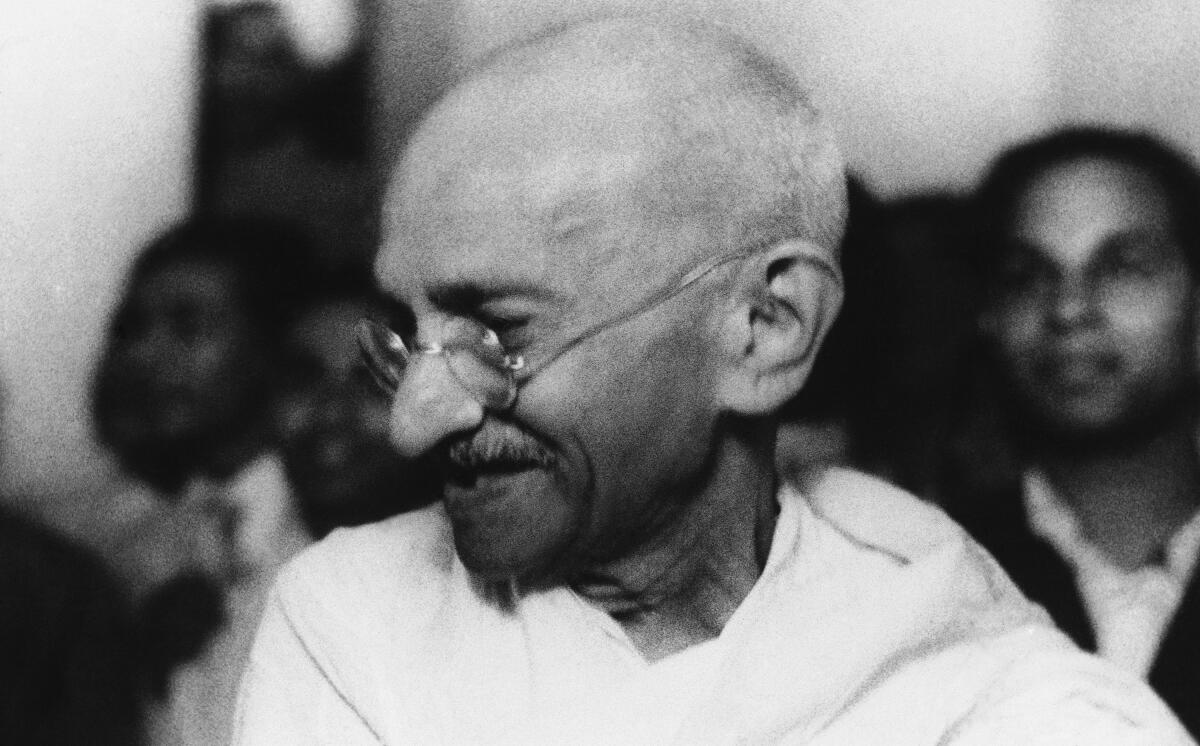

Lawson championed the philosophy of nonviolence espoused by Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi. He put those principles and protest techniques to work as an architect of the Black civil rights movement in the U.S., most notably when he helped to lead student sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville and participated in Freedom Rides on interstate buses across the South.

Lal, 63, came to know Lawson in the later years of his life.

A close bond developed between the men — one a professor of history and Asian American studies from India, a nation that had broken free of British colonial rule, and the other a Christian minister from Uniontown, Penn., who had dedicated himself to ending racial oppression in the U.S.

Lawson was pastor emeritus of Holman United Methodist Church in South L.A. and even until recently he had hosted workshops on nonviolence at the church every fourth Saturday of the month.

Lal writes a blog and posts segments on politics and culture in the U.S. and his home country of India on YouTube. He attended some of those sessions at the church.

Starting in 2013, Lawson sat with Lal for what turned out to be more than 26 hours of recorded interviews conducted over 13 sessions, with the intention of publishing the material someday. In private, Lawson was introspective, fiercely committed to racial justice and the dignity of working people and often funny, Lal said.

In those conversations, some lasting as long as three hours, the L.A. pastor detailed how Gandhi, who gained prominence as the leader of the nonviolent Indian independence movement, inspired him.

“Lawson was very clear in his mind that Gandhi was singularly the most important man in world history for having added the idea of nonviolence to the vocabulary of everyday life,” Lal said.

Lawson had been a practitioner of nonviolence since reading Gandhi’s autobiography as a freshman in college in 1947. He would never meet his hero. Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi in 1948.

But when Lawson was a young Methodist minister in 1953, he was thrilled when the church sent him to the central Indian city of Nagpur, where he worked in ministry, coached soccer, basketball and track, and studied Gandhian strategies for peaceful resistance, Lal said.

Lawson was still living in India when Rosa Parks was famously arrested for refusing to give up her seat in the whites-only front section of a racially segregated bus in Montgomery, Ala. Lawson devoured newspaper stories in the Indian press about the young Atlanta minister, King, who led a successful bus boycott to desegregate Montgomery’s bus system.

The 40 Acres Conservation League is on a mission to establish an open space where Black Californians and other people of color can feel at home in nature.

Lawson had also long been aware of Black America’s enduring affinity for Gandhi, he told Lal.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote the first of 18 essays about Gandhi in 1921, Lal said. A decade later, Howard Thurman and his wife Sue Bailey Thurman were among the first Black leaders to visit India to meet with Gandhi. He peppered them with questions about voting rights, lynching and racial segregation and explained that “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world,” according to an account published by the Gandhi Memorial Center in Maryland. Bayard Rustin spent six months studying nonviolence in the country.

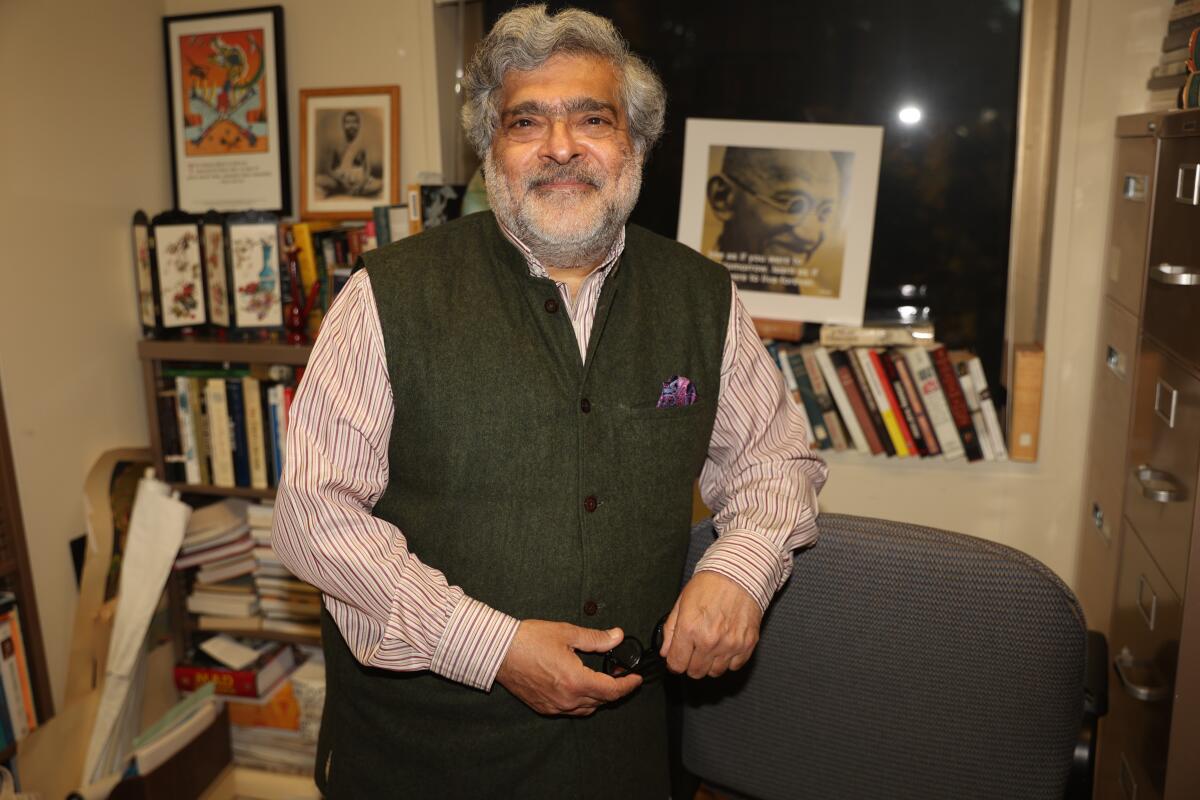

At his home in the San Fernando Valley, Lal works in a detached study, a room so crowded with shelves and stacks of books about civil rights in both India and the U.S., his adoptive country, that he steps slowly to reach the computer on his cluttered desk.

In Lal’s digital archives are hundreds of clippings from the Black press about India’s independence movement, as well as glowing assessments of the loin-clothed activist and essays urging Black Americans to find their own “Negro Gandhi.”

An article from 1922 in L.A.’s California Eagle newspaper calls for establishing “Gandhi Day.”

A tribute to Gandhi written by the pioneering Black educator, activist and presidential advisor Mary McLeod Bethune after his death praises him for showing humans “the way to lift themselves above considerations of nation or race or creed or color.”

Whenever Lal met with Lawson in L.A., he too never failed to speak of Gandhi in reverent tones, even though his admiration was already well established by then.

“He placed Gandhi, in many ways, on a pedestal,” Lal said.

After returning to the U.S. in 1956, Lawson based himself in Nashville after King encouraged him to move South to aid the movement. There, he conducted trainings in nonviolent protest in a church basement, stoking a passion for racial justice in the student activists he mentored, including his protégé, the future Georgia Congressman John Lewis. Lawson spoke at Lewis’ funeral in 2020.

Lawson became one of King’s most trusted allies. He saw in King the fulfillment of the hope that had rung out from those Black newspaper headlines of old.

“When he saw what was happening in Montgomery, he understood that finally — finally — that call for an American Gandhi was finally being heeded,” Lal said.

Describing his own trip to India in 1959, King, himself a devoted student of Gandhian principles, wrote in Ebony magazine: “To other countries I may go as a tourist, but to India I come as a pilgrim.”

During their meetings in L.A., Lawson and Lal often discussed Gandhi’s conception of ahimsa, the Sanskrit word for nonviolence. Their talks went deep. It was clear that Lawson didn’t just want to practice nonviolence. He had sought to embody the concept, to incorporate it into his very identity.

Inspired by Octavia Butler’s Afrofuturist fiction, a Sonoma County farmer helps Black Californians connect with nature and learn lessons in climate resilience.

“Gandhi coined the term ‘satyagraha’ — truth force, or soul force, a way of being in the world,” Lal said. “According to Rev. Lawson, Gandhi had created a new science. It was a comprehensive world view, a way of understanding how one leads a nonviolent life.”

Lal could also tell how much those three years in India meant to Lawson, and how the experience prepared him for the challenge of confronting racial segregation in the Deep South.

“Sometimes you see things with greater clarity from abroad than you would from your own country,” Lal said. “He came back energized when thinking about how he could play a role.”

Lal says Lawson’s view of activism as a pursuit requiring not just sound principles but strict self-discipline, accountability and a generous spirit is just as relevant today in a new era of youth protests against injustices at home and abroad.

Lawson believed that “if you feel that you’re morally bound to resist, then you have to accept the consequences as well,” Lal said. But he also believed that “conviction and compassion go hand in hand.”

Lawson understood all too well the risks involved with committing oneself to justice, peace and love.

As a conscientious objector during the Korean War in 1951, Lawson served 14 months in jail for refusing to report for the draft, and he used his imprisonment as an opportunity to study nonviolent protest. The Vanderbilt University Divinity School controversially expelled him for leading the Nashville sit-ins and he was jailed in multiple states as an activist.

It was Lawson who had invited King to Memphis in the spring of 1968 to support striking Black sanitation workers — when Lawson was pastor at Memphis’ Centenary United Methodist Church. King was assassinated on April 4, the day after delivering his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, in which he praised Lawson.

On Monday, as news spread about Lawson’s death, Lal was pleased to see that Lawson was again being celebrated as a towering figure.

Lal received an email that night from Gandhi’s grandson, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, whom Lal had invited to a conference for scholars of nonviolent resistance at UCLA in 2020. Lawson delivered a moving keynote address at the gathering about “the long, bitter but beautiful struggle for justice in America,” Lal recalls.

“So grateful that thanks to you I could meet the great man,” the email from the younger Gandhi read.

Lal wrote back with superlatives of his own about Lawson, borrowing another word that Gandhi’s grandfather had often used, an Old English term for advocate, or follower:

“He was a colossus, a true votary of ahimsa,” Lal wrote, “and a very compassionate man.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.