Massive budget cuts leave California domestic violence survivors with few options

- Share via

A spot in an emergency shelter can be a critical escape route for victims of domestic and sexual violence.

But California has long had too few shelter beds — and without a $200-million infusion from the state, the options will soon dwindle even further.

Come July 1, thousands of shelter beds could disappear across the state.

It’s not just emergency shelters: Scores of rape crisis hotlines, child abuse centers and legal service providers across California are bracing for an unprecedented 44.7% cut this summer — almost $70 million this year alone — due to a dramatic falloff in the federal Victims of Crime Fund.

Established by the Crime Victims Act of 1984, the fund has traditionally been filled by federal prosecutions and asset forfeiture, as opposed to tax revenue. Money is then disbursed to states, which allocate it to service providers.

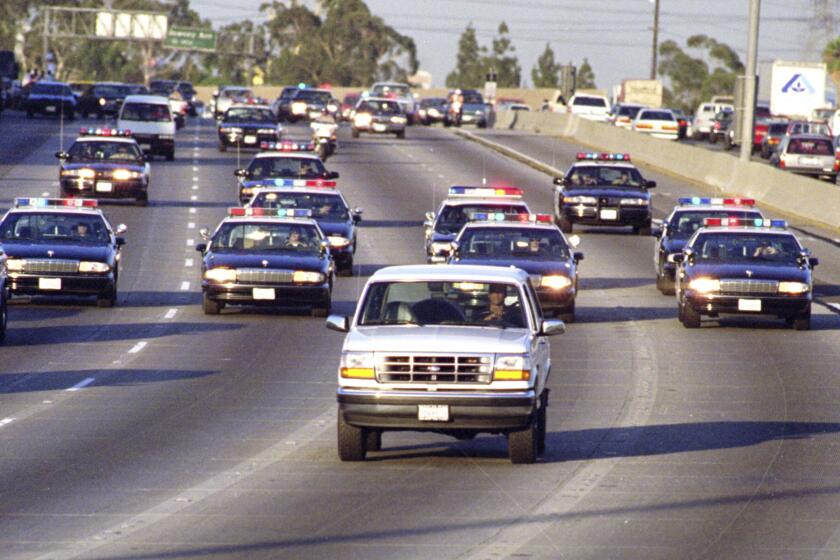

It wasn’t long after the televised spectacle of O.J.

But with fewer cases being brought and more settled out of court, the fund’s reserves have dwindled. Efforts to boost them, including the VOCA Fix act of 2021, have come too little too late, experts say.

“It’s already wildly underfunded,” said Krista Colón, senior director of public policy strategies at the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence. “We are really just asking to keep this going at the [current] level.”

Since 2019, programs in all 50 states have watched in alarm as their allotments were slashed while lawmakers looked for a way to make up the shortfall. A one-time infusion of $100 million from the state in 2021 kept California’s programs relatively intact until now.

But this year’s cut is far larger than any before, leaving providers with agonizing choices about which staff and services to sacrifice, and barely a month left to cull them.

“These cuts are very, very real — it’s not conjecture, it’s happening,” said Alyson M. Messenger, managing staff attorney at Jenesse Center, a domestic violence intervention program in South Los Angeles. “We’re talking about over a million in funding that we [at Jenesse] are going to lose.”

Messenger added that “without [shelter space], so many victims will remain trapped in dangerous and abusive relationships.”

There is no dispute Deyun Shi bludgeoned his teenage relatives in 2016, but his attorneys argue during his trial that he was suffering from mental illness.

One woman, who asked to be identified by the initial W. to protect her 2-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter after her abuser threatened to abduct them to Mexico, said she endured years of sexual assaults and physical violence until she and her children sought refuge in one of L.A.’s emergency domestic violence shelters last July.

“It was the first time I got a break from everything,” she said. “If it wasn’t for the domestic violence shelter, I don’t think I ever would have been able to get out.”

The lack of options for domestic violence victims is a long-standing problem. In the 2021-22 fiscal year, almost 16,000 callers who sought shelter from providers such as Jewish Family Service LA, where W. and her children found sanctuary, were told there was nowhere for them to go.

Because of the looming cuts, keeping a shelter bed open now means sacrificing an advocate for sexual assault survivors in the emergency room, axing the attorney who helps battered mothers file for an emergency restraining order or slashing the social worker who counsels an abused child.

“We respond 24/7 to three hospitals — how are we going to do that when we lose almost half our funding?” said Barbara Kappos, executive director at East Los Angeles Women’s Center. “It’s keeping me up at night.”

Five years after he fled the country and landed on the FBI’s list of most-wanted fugitives, Michael Pratt, the alleged mastermind behind a porn site that prosecutors say doubled as a sex trafficking ring, is back in San Diego to face federal charges.

The cuts are likely to land hardest on those who already struggle to get help, including families in poverty, LGBTQ+ survivors and those living in rural parts of the state.

“We are rarely able to get our survivors into shelters as it is,” because existing programs prioritize women with children, said Terra Russell-Slavin, policy director at the Los Angeles LGBT Center. “Any further reduction and those spots would not be available at all.”

Other providers agreed.

“For rural communities, it’s devastating,” said Paul Bancroft, executive director of the Sierra Community House in North Lake Tahoe. “Most shelters [already] have waitlists. Word will spread quickly if someone is unable to get help.”

He fears many will stay in potentially lethal relationships, believing they have no alternative.

For those who stay, violence can quickly turn deadly: Around half of all female homicide victims in the U.S. are killed by a current or former male partner, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Homicide is also the leading cause of death for pregnant women, recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

“Survivors are often making really impossible choices, of staying in or returning to an abusive home, or leaving and experiencing homelessness,” Colón said.

Domestic violence is already a major driver of homelessness for women in California, data show.

Children born from 2010 to 2024 are part of “Generation Alpha,” the demographic successor to Gen Z. They are already being called “feral,” illiterate” and “doomed,” with bad parenting by millennials and the influence of technology blamed for bad behaviors.

According to a study released this year by the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at UC San Francisco, 1 in 5 homeless women in California left their most recent residence to escape domestic violence.

In Los Angeles, nearly half of all unhoused women are domestic violence survivors, and about a quarter became homeless because of it, a recent survey by the Urban Institute showed.

Emergency shelters and transitional housing are critical to keeping these survivors off the streets, which is one reason California providers are particularly loath to cut them.

But shelter and housing are expensive. Preserving them means cutting deep into other programs, such as the Jenesse Center’s Domestic Violence Legal Clinic at the Inglewood Courthouse.

The clinic helps survivors quickly obtain a civil restraining order, which stops the abuse in more than 60% of cases, Messenger said. Such orders can be used to seek compensation for locksmiths and lost wages, as well as expediting access to CalFresh and other safety-net programs.

They also allow parents to get emergency custody of their children without involving law enforcement or risking entanglement with child protective services — outcomes many fear.

“If you call the police about a domestic violence incident and your children were in the home, that ... could result in family separation,” Messenger said. “Abusers will threaten to weaponize the child welfare system against their victims to keep them from reaching out for help.”

California lawmakers have advanced legislation that would help shore up funding for state crime victims programs in the future, while providers and their advocates press the governor for emergency cash to tide them over.

But Gov. Gavin Newsom’s revised budget proposal, released last week, did not include the reprieve many had hoped for.

For W. and other survivors, that could mean staying trapped in an abusive home.

“If I didn’t have those resources, I would have stayed there,” she said through tears. “I would have let him do whatever he wanted to me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.