- Share via

Henry Cervantes was a Fresno-born, 19-year-old son of Mexican farmworkers when the Navy told him in 1942 that he could not fight for his country.

An enlistment officer sent him home, saying the Navy didn’t take Mexicans, Filipinos or Black people. In an interview with the American Patriots of Latino Heritage, Cervantes said he directed a couple of choice epithets at the officer and declared, “I’ll prove you wrong,” before running out the door.

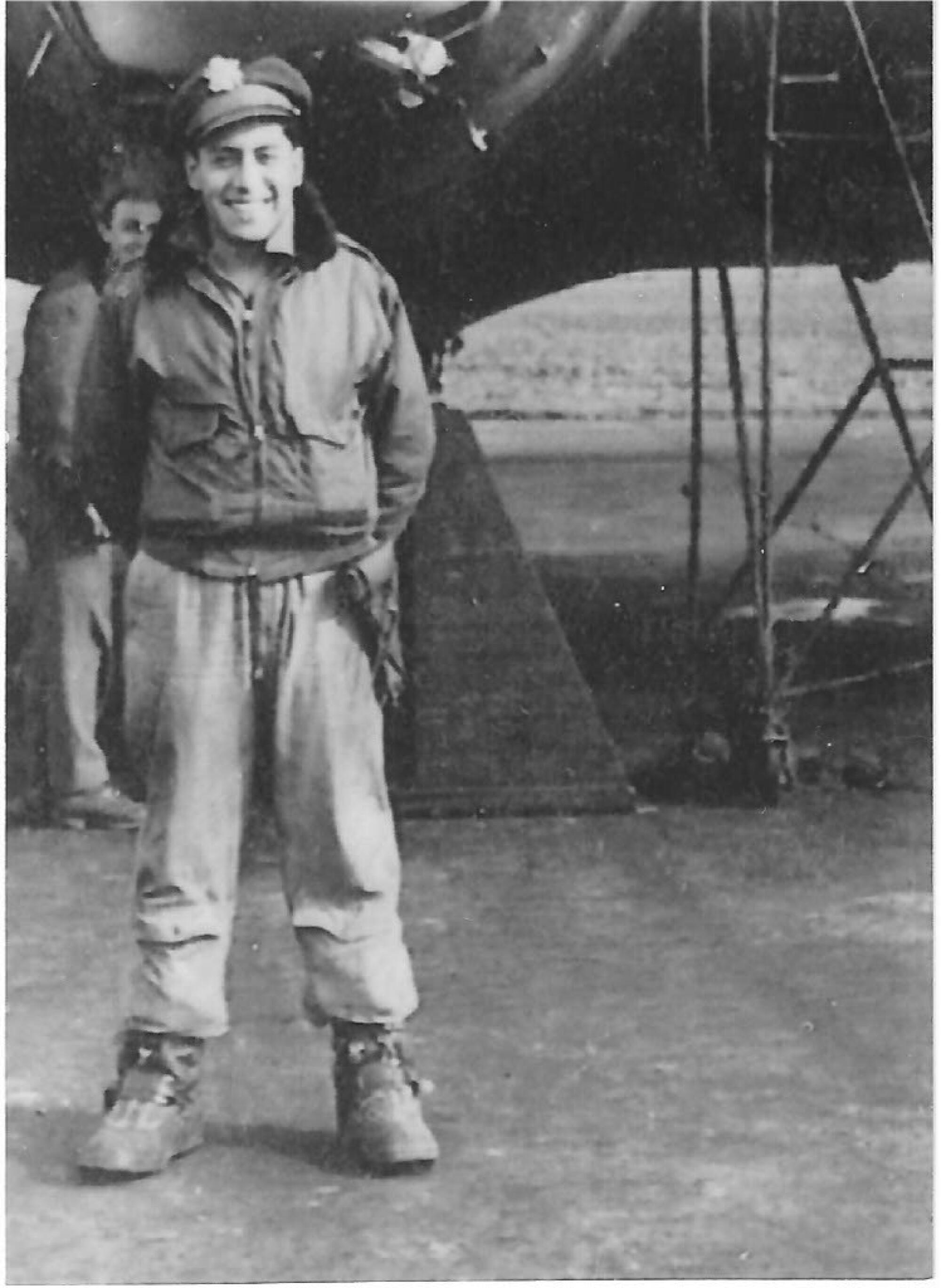

He found a spot instead in the Army and the Army Air Force, where he flew more than two dozen missions as part of the “Bloody 100th” Bomb Group. He later served as a test pilot and flight instructor, among other roles, before retiring as a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force in the mid-1960s.

Cervantes lived to see his 100th birthday before his death on April 7 at his home in Playa Vista. The centenarian is remembered by his friends as a man with “impeccable diction” and gentle spirit, but he was no shrinking violet.

Cervantes was born on Oct. 9, 1923, to a young Mexican couple, María Rincón and Pedro Cervantes. But his father left days after Cervantes was born, and his mother eventually married his stepfather, Ignacio Gutierrez, a Mexican farmhand.

When he was growing up during the Great Depression, his family was so poor they lived in a tent with a dirt floor, he said in an interview with the National WWII Museum. He couldn’t even afford shoes with intact soles. On one occasion, in fact, he was sent home from school with bleeding feet.

For the record:

9:38 a.m. May 10, 2024In an earlier version of this article, the city of Pittsburg, Calif., was misspelled as Pittsburgh.

Also, a previous headline identified Henry Cervantes as a World War II fighter pilot. He flew bombers.

His family moved to Pittsburg in Northern California, in 1934, but times were still tough. Cervantes resorted to stealing a quarter from a stash of tips collected by a nearby market, using the money to buy new shoes — which turned out to be two sizes larger than his feet; 77 years later, he reached out to Times columnist Steve Lopez, whose family owned the market, to repay the debt.

But racism and poverty did not stop Cervantes from ascending the ranks of the military. The Army drafted him six months after he was rejected by the Navy, and during basic training at the Presidio in Monterey, he took and passed a test for prospective pilots. He went on to fly B-17 Flying Fortress bombers as one of the few Latinos in his cohort.

“During his training, he was called a dirty Mexican,” said retired Judge Frederick Aguirre, who met Cervantes in 2002 at a veterans event and grew close to him through Aguirre’s work documenting the lives of Latino War War II veterans. He recalled that his friend had faced trouble earning the respect of his white subordinates, and there was “a lot of discrimination against dark-skinned Mexican persons” at the time.

Cervantes survived 26 missions during World War II as part of the 100th Bomb Group, which flew over the English Channel and Holland into German skies. Its combat missions were dramatized in the TV miniseries “Masters of the Air,” executive produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks. Cervantes told the WWII Museum that he also flew humanitarian missions to bring food and supplies to Holland, but the bombers still had to survive attacks from German fighter planes — one of which rammed Cervantes’ B-17, which somehow made it back to base and successfully crash-landed.

Cervantes also set records as a test pilot for the initial jets that were being integrated into military flight craft in 1945. By the time he retired in 1965, the Air Force had advanced from the B-17 to the B-58s, the first bombers to fly at twice the speed of sound.

Life didn’t stop moving for Cervantes, who detailed his life before and after the military in his memoir, “Piloto: Migrant Worker to Jet Pilot.” Cervantes went on to work for the Los Angeles office of Defense Contract Administration Services and for Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, managing Hispanic affairs.

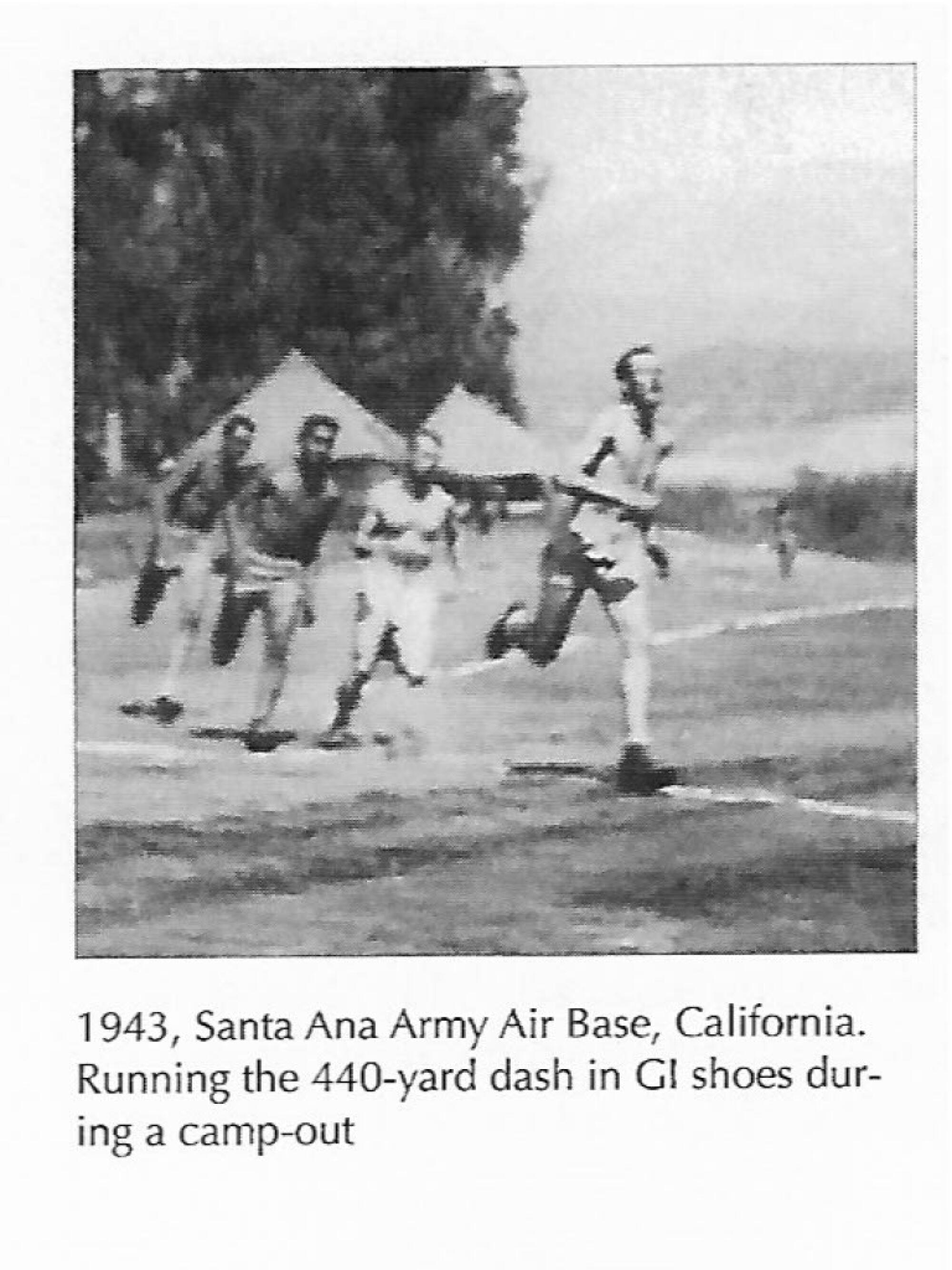

Among other hobbies, Cervantes, who had been a track-and-field athlete in high school, became an official for USA Track and Field and a officiant at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. He would often volunteer his services to the L.A. Special Olympics.

Cervantes is survived by his sister, Jennie Gonzalez, several nieces and nephews, and his longtime partner and friend of more than 60 years, Nancy Kahn. The couple first dated in 1964 when they met in the Air Force, staying together for 10 years before they broke up. Cervantes remained single his whole life.

“He used to say he was married to the military,” Kahn said. When the two reconnected after the death of Kahn’s husband in 2014, she was 75 and he was 90.

“We did everything together,” said Kahn of the last decade of their rekindled friendship. They took care of each other and enjoyed the mundane things after a long and exciting life. Hank, as Kahn calls him, was spry and agile even in his last decade.

But his health started to decline after he developed vascular dementia from a stroke five years ago. He was hospitalized after a second stroke in early March of this year and sent home on hospice care after he lost the ability to swallow.

Kahn said Cervantes died on the same date, April 7, as he’d escaped death 79 years previously when German pilots tried to ram his B-17 bomber out of the sky.

A memorial service for Cervantes will be held Monday at 1 p.m. at Holy Cross Chapel in Culver City.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.