Column: What if Bruce’s Beach was just the start? Why more stolen land is about be returned

- Share via

With polls continuing to show the public’s deep dislike of reparations, it’s easy to forget that it was only three years ago that elected officials were all in, pointing to what many had quietly thought would be a one-off as a model for righting the wrongs of systemic racism.

Easy to forget, that is, unless you are Kavon Ward.

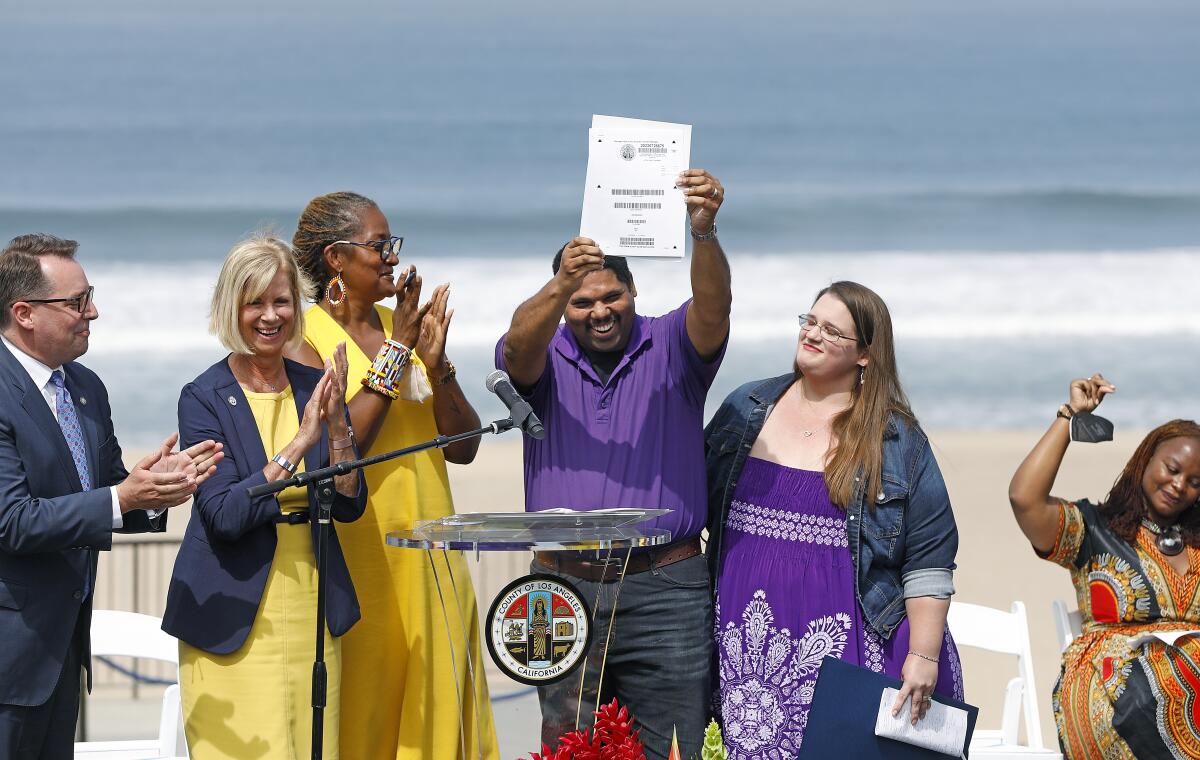

The founder of Where Is My Land was present when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill relinquishing government control of Bruce’s Beach — the property that once belonged to Willa and Charles Bruce and had been a popular lodge and dance hall for Black beachgoers in the 1900s before the city of Manhattan Beach seized it through eminent domain.

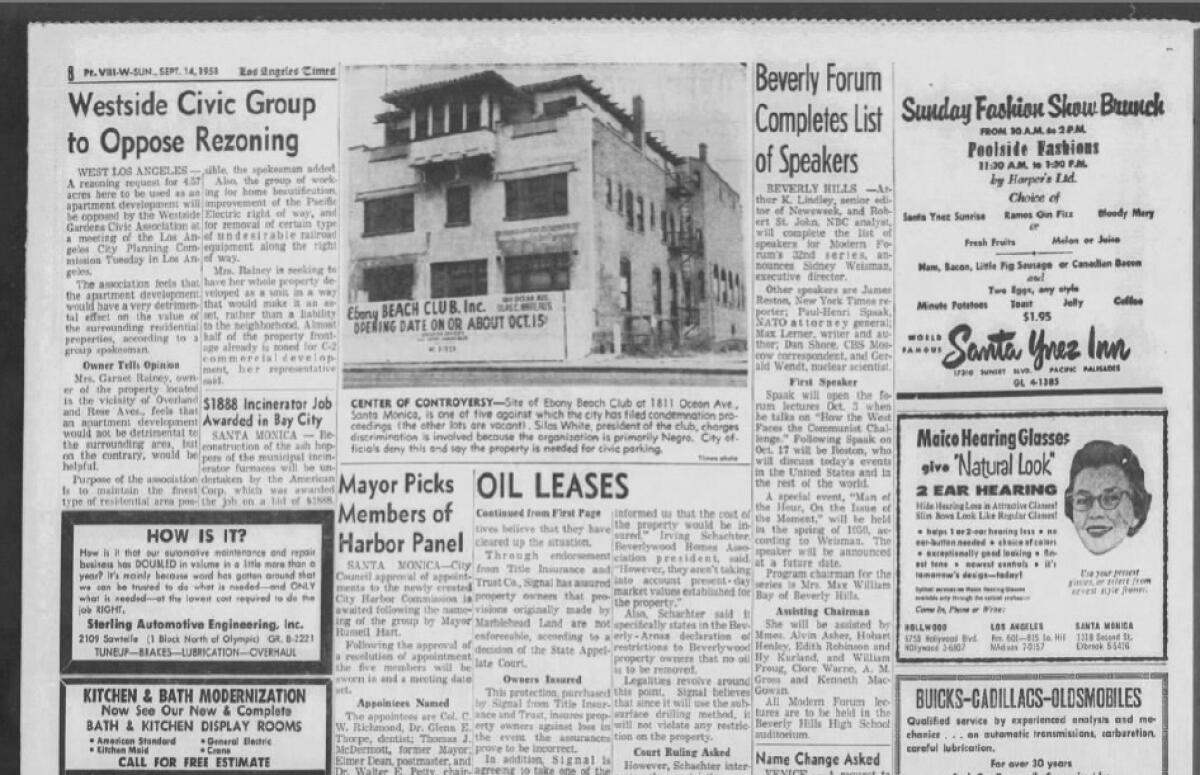

The Ebony Beach Club never saw the light of day, but the city of Santa Monica wants to make things right.

Newsom argued that what California was doing, improbably returning land to the Bruce family to keep or sell, could be — and, indeed, should be — replicated. Many publicly nodded their heads with hope. Many more shook their heads in doubt, privately. But as it turns out, the governor was actually onto something.

Last week, the Santa Monica City Council voted to consider giving back land or otherwise compensating the descendants of Silas White. The Black businessman tried to open a club for Black beachgoers in the late 1950s, in the then-segregated city, but was thwarted by an unfair use of eminent domain.

More steps remain before the Whites can officially join the Bruces, starting with council members approving the recommendations from city staff on reparations. That could happen in 90 days. But in the meantime, Ward, who worked with both families, compares the feeling of victory in Santa Monica to Bruce’s Beach.

“People thought it was a one-off and dismissed the work I did,” she told me. “They were like, ‘You just got lucky. All the stars were aligned.’ Well, I’ve done something that’s never been done before — twice.”

Now the question is can it happen a third time? And a fourth, a fifth and a sixth? And if so, if this becomes a full-fledged trend, what will that mean for long-accepted principles around property ownership and the generational accumulation of wealth? Who will be the new winners and who will be the new losers?

Because in America, we’re almost all living on stolen land. It’s an uncomfortable truth, so we rarely question the justness of it. But that could be changing.

“We need to be taking a hard look at our government institutions that have been traditionally white-male-dominated and, quite frankly, white supremacist, and correct some of the harmful actions of the past,” Santa Monica Councilmember Caroline Torosis told me. “The more that we normalize options and processes for folks to really have reparative justice, the more it becomes a mainstream thought.”

And yet, I suspect this potential to normalize an economic reordering of society is one reason why there’s so much opposition to reparations — even as the California Legislature has started considering more than a dozen bills recommended by a state task force to address the lasting harms of slavery and racist government policies.

One of those bills, Senate Bill 1050 from state Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena), would empower the state to investigate allegations of racially motivated property takings. Crucially, it also would “establish a process for providing compensation to the rightful owner,” presumably making it easier to do what Ward did in Manhattan Beach with Bruce’s Beach and in Santa Monica with what would have been the Ebony Beach Club.

“It took a lot to get this done,” said Ward, who offered input on SB 1050. “You don’t see all that goes on behind the scenes and so people just think that it’s easy. But it’s not.”

Few understand this more than Indigenous Americans, creators of the original Land Back movement, designed to reclaim and steward ancestral territories that were taken and encroached upon more than a century ago.

Their fight for control of mostly rural wildlands is slightly different than the ownership battles over developed urban neighborhoods. For one thing, it’s not just about land for the tribes. It’s about culture and identity and healing, and about having sacred spaces to practice ancient traditions.

And yet, they also have notched some surprising victories lately.

In 2022, as Black people were still figuring out how to replicate what happened with Bruce’s Beach, the Tongva were given back an acre in Altadena, marking the first time in roughly 200 years that Los Angeles’ first people had land to call their own. Also that year, more than 500 acres of redwood forest in Northern California was returned to the InterTribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council.

In 2023, 6.2 acres in Orange County was transferred to the Tongva and Acjachemen people. And so far this year, the Ohlone people regained 2.2 acres of land near San Francisco. The Yurok people also struck a deal to get back 125 acres in Humboldt County and have similar hopes for their ancestral land along the Klamath River, which is emerging after the removal of four hydroelectric dams.

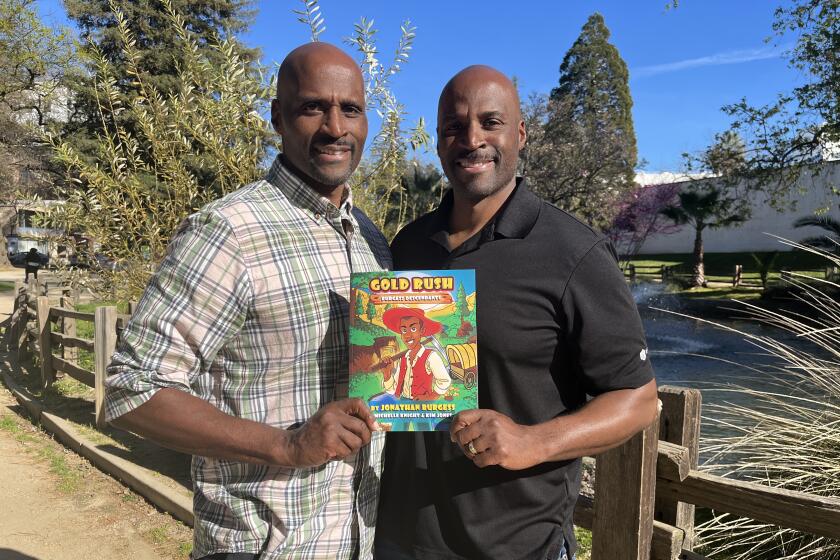

Brothers want California to return land owned by their ancestors. But a task force’s debate over eligibility for reparations is complicating matters.

Meanwhile, Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles) and Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara are taking on the long lamented displacement of thousands of mostly Latino families, supposedly to build housing, but ultimately to build Dodger Stadium.

Assembly Bill 1950 would provide reparations — Carrillo’s word, not mine — to the descendants of residents of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop, now collectively known as Chavez Ravine. The biggest ask involves land. Each family would be entitled to city-owned land that’s comparable in size to what they lost or compensation for the value of it, adjusted for inflation.

“The city robbed the residents of these three communities of generational wealth,” Carrillo said in explaining why she introduced the bill, which is still in early committee hearings.

Indeed, there’s a groundswell of new thinking about confronting the can-of-worms consequences of stolen land. And with each victory, whether it’s the process in Santa Monica or Humboldt County, there’s more momentum to achieve the next one.

“There’s a clear openness to correcting injustices [and] of doing right by people, especially in a time in which housing is a predominant conversation,” Carrillo said. “And we begin to see just how incredibly biased policies of the past impacted people of color.”

::

Big questions aside, 90-year-old Connie White is still wrapping her head around the fact that her family might actually get their Santa Monica land back — or at least compensation for it.

She was in her 20s when she watched her father, Silas, put his dreams and his savings into turning an old building on Ocean Avenue into a hotel and club. He had owned several businesses, including a laundromat and a hamburger stand, but this was to be the “crown jewel.” Nat King Cole had agreed to be a charter member.

But a few months before the Ebony Beach Club was scheduled to open, the city seized the building and the surrounding land. White sued, but he lost. Shortly after that, he was diagnosed with cancer. He fought it, but got sicker. Then the city condemned and demolished the building, replacing it with a parking lot.

“That really hurt him a lot,” White told me. “And then he started really not taking care of himself as much as he had before. And he was very, very depressed. And then, in 1962, he passed away. He was only 57.”

She thought it was over. That there was nothing more anyone could do. She never even mentioned what happened to other relatives, including her cousin Milana Davis. Then came Bruce’s Beach.

“Connie said to me one day, ‘You know, my father had property in Santa Monica that they took away from him. Maybe I should contact Where Is My Land,’” Davis recounted. “I said, ‘Yes, I think, you should.’”

Given a choice on reparations, Davis said she would prefer to get land back, though that’s a complicated proposition since the luxury Viceroy Hotel now occupies it.

White, meanwhile, said she doesn’t know what she wants yet, other than for people to know what happened to her father — and to demonstrate to other families, other people of color who have been wronged, that they don’t just have to accept their land being stolen.

“That’s my hope,” White said.

“Many years ago, my dad talked to me and we were talking about the definition of justice,” she added. “He said, ‘In your lifetime, if you see a way to bring justice, I want you to pursue it.’ So that’s what I did.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.