13 charged in Mexican Mafia collection racket in L.A. County jails

- Share via

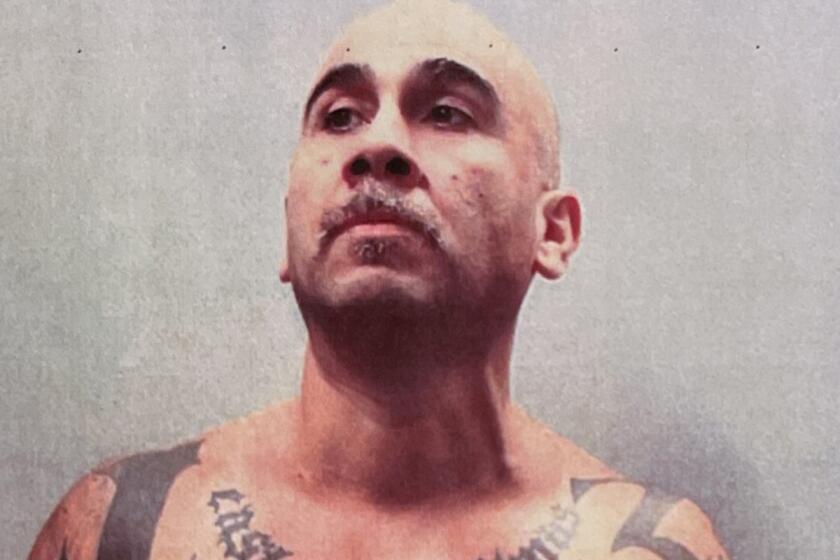

Authorities this week charged 13 people with collecting money from drug sales and extorted commissary goods inside the Los Angeles County jails on behalf of Michael “Mosca” Torres, a Mexican Mafia member who controlled the jail rackets until his death in July.

The case filed Wednesday by Los Angeles County prosecutors offers yet another illustration of how the Mexican Mafia, a prison-based syndicate of Latino gang members, controls and extracts money from inmates held at the nation’s largest jail complex.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

Torres, 59, oversaw this system using contraband cellphones in a state prison hundreds of miles away, where he was serving a sentence of 133 years to life for attempted murder, conspiracy and witness tampering. Said to have been inducted into the Mexican Mafia in 1994, Torres was stabbed to death in the exercise yard at California State Prison, Sacramento, on July 6 in what law enforcement officials suspect was an internal power struggle over control of the L.A. County jails.

The crimes alleged in Thursday’s case predate Torres’ death. The defendants are charged with extortion, conspiring to commit extortion, gang participation, smuggling drugs into a jail, conspiring to smuggle drugs into a jail and conspiring to commit assault.

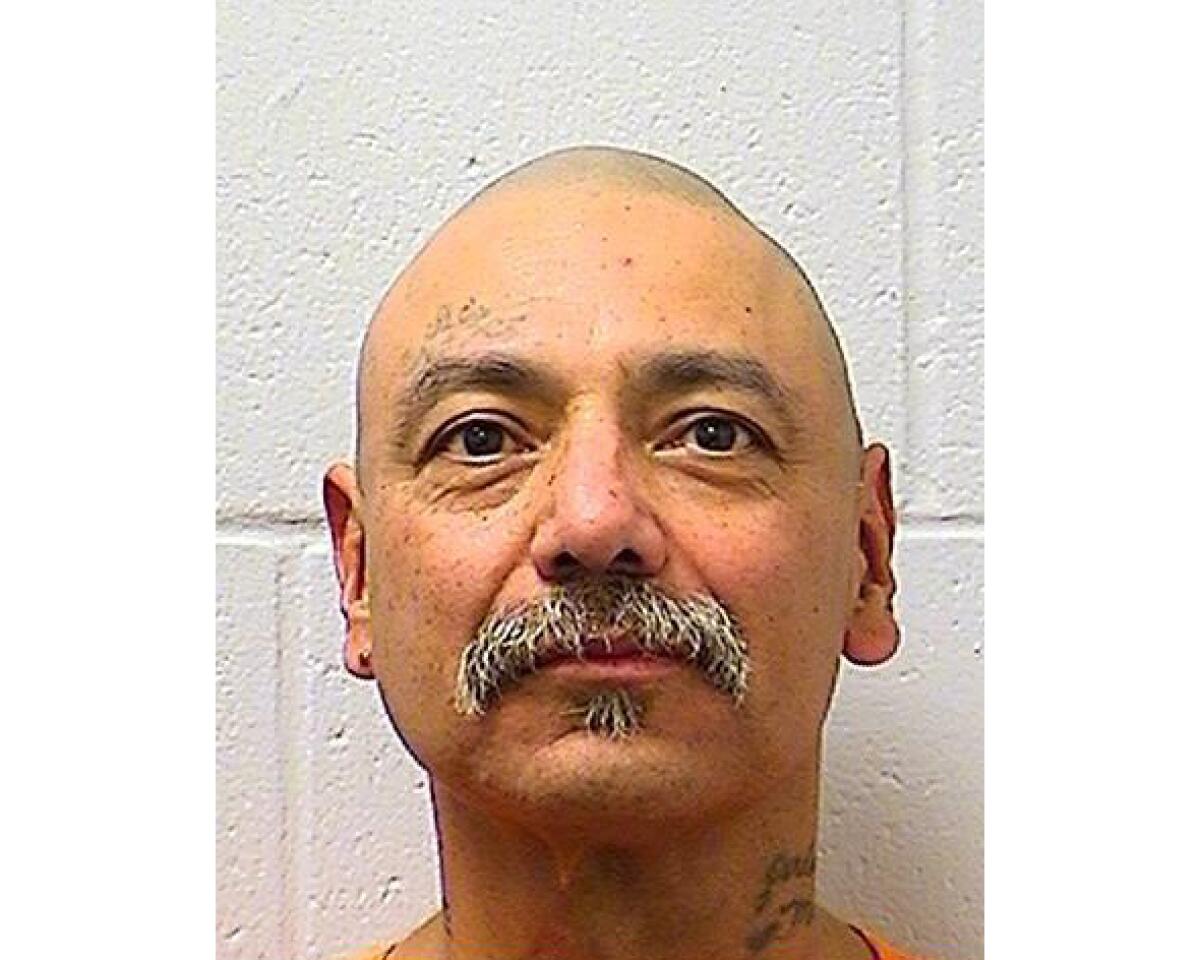

The case centers around Jose Martinez, 35, a reputed member of the Rockwood gang nicknamed “Duke,” who was described in a police report as an “out of custody facilitator.” Martinez is accused in court documents of relaying messages between inmates and gathering money from the sales of drugs. He also allegedly collected the proceeds of extorted commissary goods.

A gang member was caught smuggling drugs into Los Angeles County’s main jail. He was, authorities say, just one cog in the Mexican Mafia’s lucrative operation in the county jails.

Police reports reviewed by The Times state that for every $10 a Latino inmate spends at the jail’s commissary on snacks, clothing or hygiene supplies, he must contribute $1.50 worth of goods to a collection called the “kitty.” Those items are then resold, creating a secondary market that is cheaper than the jail-authorized one. “The contribution of purchased items was enforced with violence and the threat of violence,” prosecutors wrote in a complaint.

On a recorded jail phone in March 2022, Martinez told Pharoah Brooks, 46, an alleged Clanton 14 gang member called “Blackie,” that Brooks needed to come up with $600 a week in kitty sales from the dormitory he oversaw at North County Correctional Facility, according to a police report.

Brooks allegedly promised Martinez he would “forward all — all the grocery money to you,” which investigators believed was either kitty or drug proceeds. Narcotics are sold at a staggering markup in the county jails. A gram of heroin worth $50 on the street, for example, can cost 20 times that in jail.

When sheriff’s deputies and FBI agents raided Martinez’s home in Compton in 2022, they seized envelopes stuffed with cash that were earmarked for different “shot callers” within the jail, according to a police report.

Authorities also found, hidden inside a book in the Compton home, handwritten “roll calls” that listed the names, gangs, nicknames, booking numbers and court dates for all Latino inmates in the jails. This documentation, the report says, allows the Mexican Mafia to “track down persons in bad standing, persons that owe money, to coordinate the movement of drugs and communications, to account for taxation revenue such as the kitty and other enterprise business.”

A defense attorney was charged in a federal indictment with conspiring to murder a Mexican Mafia member who had fallen out of favor with the prison-based syndicate.

Martinez and Brooks were recorded discussing an inmate who was holding himself out as a Mexican Mafia member, according to a police report. Saying the man was called “Mikey from Florence,” Brooks asked Martinez to “run a make on that.”

Posing as a Mexican Mafia member can draw a death sentence from the gang. Torres had been serving life in prison for shooting a San Fernando Valley gang member in 2003 who was shaking down drug dealers and prostitutes by falsely claiming to represent the organization.

After speaking to Brooks, Martinez got a call from another inmate, Marco “Mugsy” Lujan, according to a police report. Martinez told Lujan, 46, a reputed member of the Laguna Park Vikings, that “uncle” confirmed the supposed Mexican Mafia member “does not exist.”

“OK,” Lujan replied, according to the report. “We are going to take him out.”

A day later, three inmates attacked a “completely defenseless” Michael Nunez in his dormitory at North County Correctional Facility, the police report says. Nunez curled up on the floor as Ariel Pereyra, Andy Dominguez and Angel Grajales allegedly beat him for a minute and 30 seconds until sheriff’s deputies broke it up, according to the report. Nunez was hospitalized with head trauma.

The charges unsealed this week show little has changed in the operations of the jail rackets since Torres first implemented them while awaiting trial 20 years ago.

Just as Martinez is alleged to have relayed orders and collected money from outside jail, Torres used his wife to field calls from inmates and manage his money, according to recorded calls played at his trial. Deputies also seized from a Torres underling two roll call lists and several handwritten messages from his boss.

The syndicate once relied on associates on the streets, but court data showed that smuggled phones have given imprisoned leaders greater control over drug deals.

“I’m suppose to be receiving money from you vatos once a month,” one read, “and so far for the last 3 [months] I haven’t received nada. ... So to avoid any [confusion] this is how it’s going to work from now on. Whenever one of you have money for me, you’ll have your senora” — lady — “put it on my books and then have her give a note to my senora for me stating how much and who it’s from. This way I’ll know for sure who’s money is coming in and who’s not.”

Another was addressed to a shot caller who had been collecting money from a jail facility in Castaic.

About two-thirds of the Mexican Mafia’s 140 members are held in California prisons, which are inundated with illegal cellphones. They use the phones to traffic in drugs, collect money and order murders.

“Months have passed and I haven’t received nada,” Torres wrote, “so either you’re pocketing it or you have it. Produce it or get dealt with. This is no exceptions. If people want to take my kindness for weakness then step up.”

When Torres was held at the lockup in downtown L.A., a detective testified, inmates turned to him before submitting to guards’ commands. “They would shout out things like, ‘M, do I comply?’ Or, ‘Hey carnal, do I go along with the program?’ Things of that nature,” Det. Javier Clift testified. “And Mr. Torres always told them, ‘Go ahead.’”

“Very polite man,” Clift said of Torres, adding: “You have to be very careful with these guys, because they know how to work individuals and try to get on their good side.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.