Hundreds of people exposed to measles at California hospital, officials say

- Share via

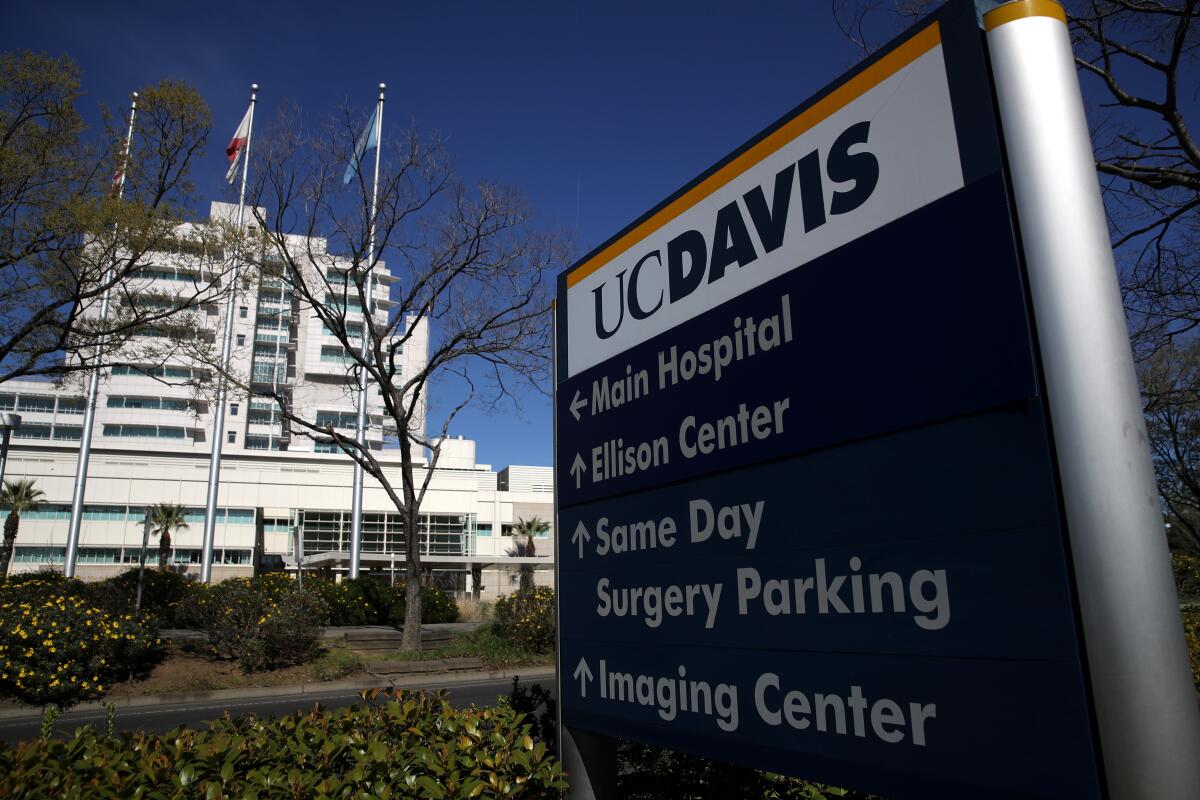

Hundreds of people were exposed to measles after a child with the virus was seen at a Northern California hospital, officials said.

As many as 300 people were exposed to the child, who was evaluated at UC Davis Medical Center’s emergency department and confirmed to have measles, according to health officials in Sacramento and El Dorado counties.

The child was seen between noon and 5 p.m. March 5 at the Sacramento hospital. People who are unvaccinated or don’t know their measles vaccination status “are at risk of developing measles from seven to 21 days after being exposed,” the Sacramento County Public Health Department said in a statement.

The exposure highlights growing concern about the reemergence of measles nationwide. Four cases have been reported in California, including one in Los Angeles County involving a person who arrived Jan. 25 on a Turkish Airlines flight while infectious and later visited a Chick-fil-A restaurant in Northridge.

Another measles case was recently reported in San Diego County, involving a 1-year-old who had traveled overseas. Other people were potentially exposed at locations including Grossmont Pediatrics of La Mesa on Jan. 31 and the emergency department at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego on Feb. 1.

A recently arrived traveler at Los Angeles International Airport is the source of the first case of measles in L.A. County since 2020.

Nationwide, there have been 45 measles cases in at least 17 states so far this year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There were 58 in all of 2023.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses and can be spread through the air. The last significant year for measles nationally was 2019, when there were 1,274 cases — the most since 1992.

Of the cases reported between Jan. 1 and Oct. 1, 2019, 119 people needed hospitalization. Sixty patients suffered from pneumonia, and one had encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain. Among those hospitalized, 20% were younger than 1 year old. Children under 1 are too young to be vaccinated.

Fueling concern this year is a cluster of measles cases reported last month in an elementary school in Florida. The state’s surgeon general, Dr. Joseph Ladapo, has come under criticism for his response after declining to order unvaccinated children to stay home during the outbreak. That response goes against routine public health recommendations of barring unvaccinated children from classrooms in the midst of an outbreak.

Ladapo has faced criticism before, including for statements on COVID-19 vaccinations that were rebuked by officials with the CDC and Food and Drug Administration.

In Chicago, there have been four measles cases at a migrant shelter. In response, more than 900 residents of the shelter were vaccinated against measles over the weekend, local health officials said.

A day before the first Chicago case was publicly identified, officials reported another measles case — the first in the city since 2019. That case is not linked to the migrant shelter. Although the person did not travel recently outside the city, they did interact with others who had traveled domestically and internationally.

Florida’s quack surgeon general Joseph Ladapo dismisses the threat of measles, but the danger is deadly and real.

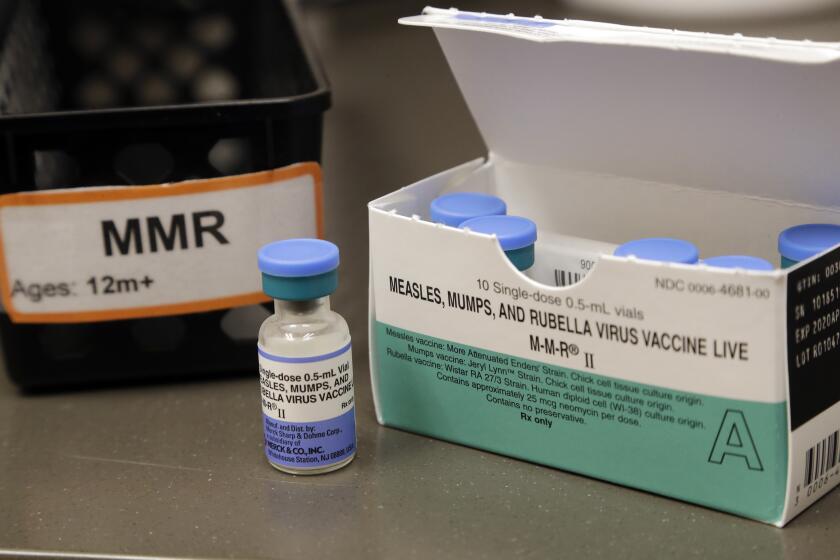

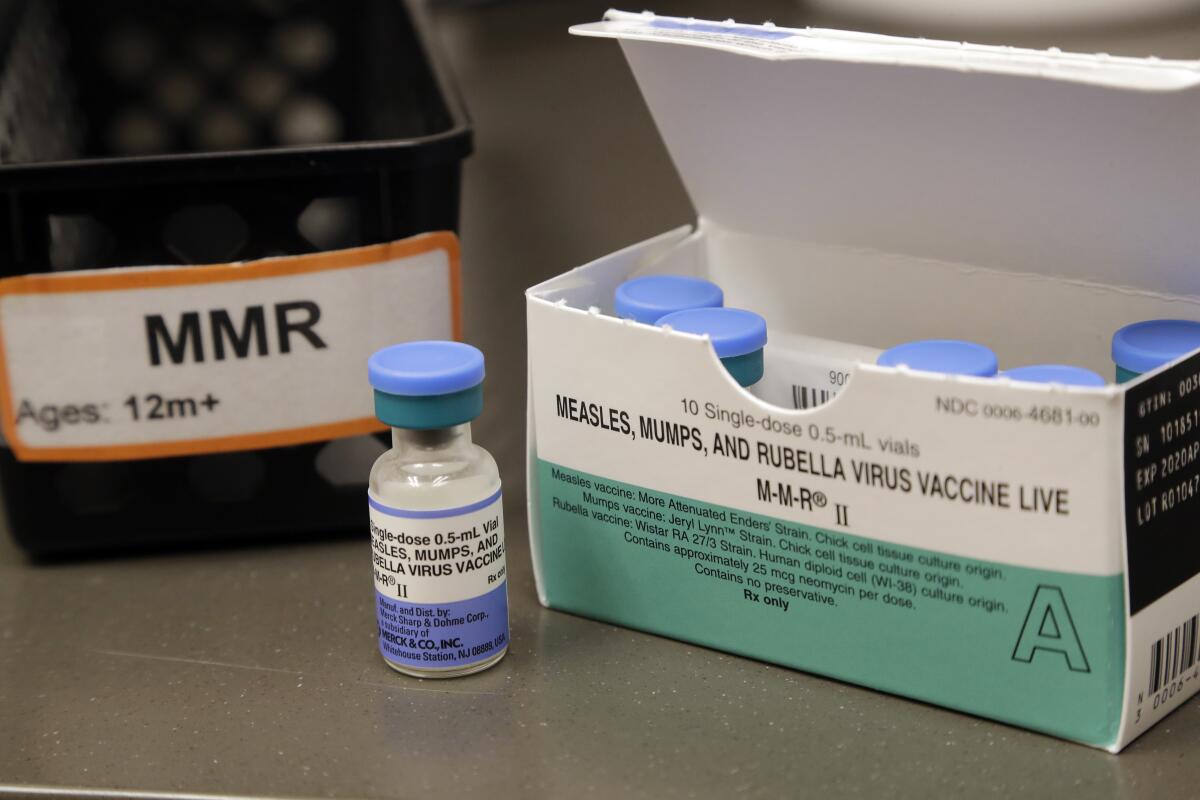

The vaccine against measles — which has been around since 1963 in the U.S. — is routinely given to children and is highly effective. But health officials nationwide have seen what can happen when vaccination rates decline.

The 2014–15 Disneyland measles outbreak was linked to more than 140 cases among residents of the U.S., Canada and Mexico, most of whom were either not vaccinated or had an unknown vaccination status.

Factors in the Disney outbreak included declining vaccination rates, in part inspired by a 1998 Lancet report, which was later discredited, that linked the measles vaccine to autism. That report’s conclusion was retracted by the Lancet in 2010.

An editorial co-authored in 2011 by Dr. Fiona Godlee, then editor in chief of BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal), called the original Lancet report an “elaborate fraud.” The editorial accompanied a report by British investigative journalist Brian Deer that documented how a key author, Andrew Wakefield, manipulated data to prove something he “knew” before he started his research. British officials revoked Wakefield’s license to practice medicine.

Nonetheless, the damage was done: Public confidence in the vaccine dropped, and measles cases rose.

Sentiment toward the vaccine seemed to shift after the Disneyland outbreak. Measles vaccination rates rose among California kindergartners, likely because of a change in state law in 2015 that strengthened requirements that schoolchildren be vaccinated against measles and other diseases.

Prior to that change, California parents could cite personal beliefs in asking children to be exempt from routine vaccination requirements; the 2015 law allowed only medical exemptions for children entering daycare and kindergarten. Parents can decline to vaccinate children who attend private home-based schools or independent studies off-campus.

A very high percentage of the population — ideally, 95% or greater — needs to be vaccinated against measles to prevent outbreaks.

Measles ravaged California from 1989 to 1990, when more than 15,000 cases were reported, causing about 70 deaths. That outbreak prompted health authorities to recommend a second dose to the measles vaccine schedule.

In 1977, Los Angeles County health officials faced two measles deaths, three cases of brain inflammation and numerous cases of pneumonia requiring hospitalization, according to an article in the journal Vaccine. County health officials ordered 50,000 people with no proof of immunity to stay away from schools; within days, “most were back at school with proof of immunity, and the number of reported measles cases dropped precipitously,” the report said.

Rates improved nationwide following the creation of the federal Vaccines for Children program in the 1990s, which paid for vaccinations for those who couldn’t afford them.

More parents are choosing to delay childhood vaccinations, such as the MMR vaccine. Doctors worry toddlers remain vulnerable as measles spreads.

Some pediatricians in California have expressed concern about parents requesting delays in vaccinating their young children. While California does not keep track of vaccination data for all children, some pediatricians say they’ve seen more parents asking about delays since the COVID-19 pandemic brought out more misinformation about vaccine safety.

Health officials in the Sacramento area are urging those who may have been exposed to measles to contact a doctor or healthcare provider if they are pregnant, care for an infant, have a weakened immune system or are not immunized.

“Do not go to your provider in person or go to the emergency department,” the Sacramento County Public Health Department said, as this risks exposing others.

After exposure to the measles virus occurs, symptoms can appear in seven to 14 days, causing high fever, cough, runny nose and red, watery eyes. Several days after initial symptoms begin, the telltale measles rash can appear.

The recommended measles vaccination schedule is a first dose at 12 to 15 months of age and a second at 4 to 6 years.

The virus is especially dangerous for babies and young children, the CDC says.

Generally, 1 in 5 unvaccinated people in the U.S. who get measles need to be hospitalized; 1 in 20 children with measles gets pneumonia; and 1 in 1,000 children with measles develops swelling of the brain that can lead to convulsions and result in permanent loss of hearing or intellectual disability, the CDC says.

“Nearly 1 to 3 of every 1,000 children who become infected with measles will die from respiratory and neurologic complications,” the CDC says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.