Column: Was L.A.’s Ellen Beach Yaw the proto-Taylor Swift?

- Share via

OK, so her fans didn’t wear wrist-to-elbow bead bracelets, and she didn’t exhort them to register to vote — although her husband crusaded ardently for giving women the vote.

In spite of those shortcomings, the most famous California singer you probably never heard of did perform for the king and queen of England, sing at Carnegie Hall and in the grand opera houses of Europe, and record her voice for some techie named Thomas Edison.

Her name was Ellen Beach Yaw. She was a coloratura soprano with an almost freakish vocal range — nearly four octaves, it was said, a voice capable, if any voice is, of the wineglass-shattering stunt of legend.

Before the flickers were even a flicker in Hollywood’s eye, Yaw was a celebrity across the continent in New York, across the ocean in Europe, and especially here, where she became the apple of the eye of Harrison Gray Otis, the first publisher of the Los Angeles Times.

He praised her unstintingly and uncritically in his newspaper, and gave her her nickname — “Lark Ellen.” In her honor he renamed his charity, a boys’ orphanage, the Lark Ellen Home for Boys.

His fond gaze upon her is fixed forever in a photo of the two of them in 1913, at the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, where, at his request, she sang her own composition, “California, Hail the Waters,” whose lyrics ran to “Lift your voice in gratitude, a river now is here, whose glorious waters flowing free a paradise will rear.”

As she sang, the woman nicknamed for a bird had to fight the wind, which blew the ostrich feathers on her hat into her face.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

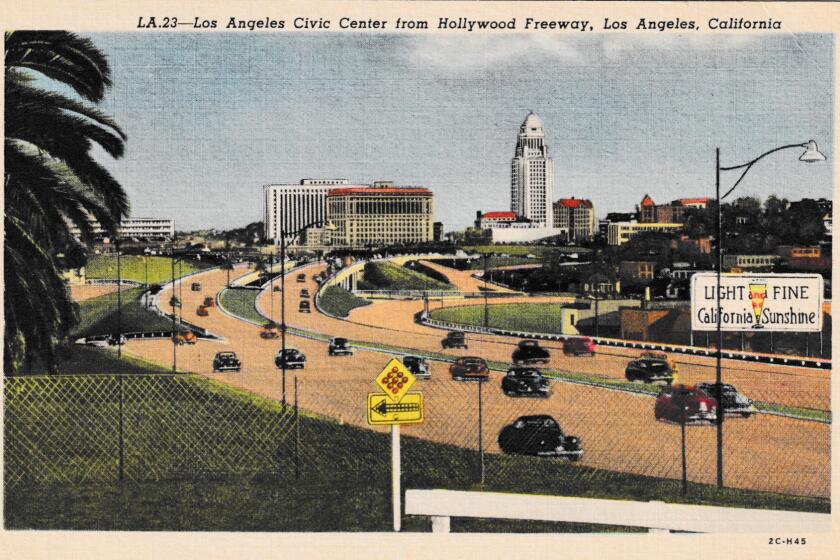

That nickname, Lark Ellen, is still, 75 years after she died, borne by an avenue in West Covina, near the fabled “glass house” estate that she built for herself.

Other newspapers’ nicknames for her — the California nightingale, the California skylark — were not just about her immense vocal range, but about the wonder and novelty that California, of all places, could claim such a woman. Yaw’s near-contemporary, Isadora Duncan, younger by about 10 years, was born in San Francisco, but she soon high-tailed it to Europe and is hardly ever thought of as Californian.

Yaw was a Californian by choice, not by birth. Birth was Boston — not the erudite one but a namesake village in upstate New York. It was home to fewer than 2,000 souls when Yaw was born there, in 1869.

Stories of Yaw’s early musical talent were many and varied: Her first warbling was with the birds, or with her mother, or to a startled Sunday school teacher. Once this infant phenom was discovered, she was put in a gingham dress and sunbonnet to sing on a circuit of local weddings and Methodist church socials.

With the death of the wage-earning father, the family struggled in true 19th century Dickensian fashion. Yaw was haphazardly musically schooled as money was available to pay for it, and the family moved to Minnesota, and then to Southern California.

All the while, Yaw sought professional instruction. She worked as a stenographer for pay-as-you-go lessons. She made money on regional concert tours as well, and once her family had settled here, she or her musical sister or both are supposed to have taught music briefly at Throop University, a general-education school in Pasadena that soon became the science powerhouse CalTech. The Yaw sisters performed home concerts for friends, maybe for money, or maybe just for tea and sandwiches.

Yaw made the train trip to New York to study, and then headed for Paris, to work with the Italian baritone Enrico Delle Sedie. The papers reported that she sang for the renowned French composers Massenet and Saint-Saens, whose works she would perform on the concert stage.

You think this year’s rains were bad? The floods of 1938 were so epic they led to a massive re-engineering of the L.A. River that vastly reduced the ability to recharge groundwater.

It set a pattern for her career in the 1890s and into the new century, traveling a loop from London to Paris, sometimes with a side gig in Italy, or Switzerland, then back to New York, and rewarding tours in her native country.

Newspapers that loved her found no news nugget too small to croon over. The Times quoted an unnamed “throat specialist” who examined Yaw’s larynx and declared her vocal cords to be “finer than any he had ever seen or heard of.”

And then there was her ultimate pop star accolade, shared with Paul McCartney, Britney Spears and Mark Twain: rumors of her death were exaggerated. Hers, in 1897, bounced from an Atlanta newspaper to Waterloo, Iowa, to Rochester, N.Y., reporting that she had died onstage in San Francisco, bleeding to death from a burst jugular vein “while singing a high note.” From Colorado, Yaw assured the mourning world that she was alive and well.

And also in the fashion of pop stars, she got a couple of big happenstance breaks.

For one, Lady Valerie Meux, a banjo-playing music hall singer who married a British baronet, became a social sensation and quirky philanthropist, and was known to drive around London in a carriage pulled by a pair of zebras. She became Yaw’s patron and sent her to study in Paris.

Meux happened onto Yaw because of another renowned Londoner, Sir Arthur Sullivan. He was the composer half of Gilbert and Sullivan, the Lennon-McCartney of sprightly operettas, back when operettas were both the movies and the pop music of their day — the must-see shows, the must-sing songs.

He wrote his last complete comic opera for Yaw’s voice, as the lead in “The Rose of Persia.” The opening-night review, in November 1899, from The Times, in London, said: “The only important defect of the music is that the leading soprano part has been written for the curious high notes possessed by Miss Ellen Beach Yaw … but it can hardly be hoped that there are as many owners of these notes as will undoubtedly be required before long. … Putting aside Miss Beach Yaw’s high notes, she looks very pretty and acts with some charm.”

And sure enough, she lasted a reported scant 13 performances. Gilbert and Sullivan fan sites carry the back-and-forth offstage drama.

Decades afterward, the daughter of the woman who replaced Yaw wrote, “Well, the opera opened, and Miss Beach Yaw was not a success. She was so thin that she had to have ropes of jewels draped round her arms, and to help her voice, used to eat a grape in the wings, and spit it out before going on to sing! Mother was asked to play the Saturday matinée, ‘as Miss Beach Yaw found it too exhausting to play two shows.’ And the next Monday night, Mother took over the leading role and played it until the end of the run.”

Sullivan wrote a few days after the opening that he thought he had “made a mistake” in casting Yaw, “certainly not a success at present, and that I fear she hasn’t got the stuff in her to improve.” But he listened to the performances by phone over the next week, and changed his mind. “I find Miss Yaw improving rapidly every night.” Yet he was overruled by the opera company owner, who fired Yaw. Sullivan wrote that he learned of it when “Miss Yaw came and told me that she had been summarily dismissed, and told not to come to the theatre again — she was in a great state of grief and indignation.” Word was put out that she was ill and couldn’t continue the part.

As fulsome as some newspapers were about Yaw, here and abroad, there were other critics of the “emperor has no clothes” variety. Hers was certainly a formidable voice, but the consistent critique was that her signature high note was uncertain and unstable. Even she told the New York Times, “Of course, I can’t give much musical value to a note as high as that. It must be quick and staccato.”

The San Francisco Daily Times in 1901 was unsparing as a scalpel. “She is a freak vocalist, and squeezes out a high note, thin and colorless, and of no value for musical purposes. … there are many sopranos who can make a noise like Ellen Beach Yaw, but choose not to.”

You can listen to her recordings made over the decades, keeping in mind the nature of the technology too.

Los Angeles bills itself as the home of endlessly clement weather. But Southern California’s mix of microclimates isn’t immune to dramatic storms.

In 1902, she shared a Paris stage with Sarah Bernhardt at a memorial for the assassinated American president, William McKinley, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” (a later rendition of it here).

In 1908, she made her debut at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, singing the renowned “mad scene” from “Lucia di Lammermoor,” a bit that she had sung the year before in Italy.

The New York Times was not bowled over, but a critic for the New York World gave her performance full marks. Her fabled high note was “an extraordinary note — a real note — not merely touched but held a G in altissimo ... the audience gape[d] with open-mouthed astonishment.”

She took nine curtain calls, but hers was a one-and-done performance. Any buzz about a three-year contract with the Met was just that — buzz. She was already on the record as saying that she was “never happy” doing the “Rose of Persia” role: “It is no pleasure for me to sing in light opera.”

Anyway, the solo concert stage better suited her voice and her bank account. As she told one of her proteges, “Opera is very hard work and I can make more money in one concert than any opera company can pay me!”

For all of her high-note renown, her voice never ranked her with her contemporaries, the great operatic sopranos known by single names — Nilsson (Christina), Patti (Adelina), and Melba (Nellie, who had a dessert named after her). And it must also be said: “Yaw” was not a name to conjure with. (In the singular, it describes the motion of a ship; in the plural, it is a now-rare, disfiguring tropical disease.)

Antisemitism is as old as time. In Los Angeles, prejudice against Jewish people took on new and more public forms in the 1920s and 1930s and beyond.

When Yaw married, in 1907, one newspaper critic was satisfied that her husband’s name was “a more musical name than Yaw anyway.”

About that marriage. Her first husband was at least as much a character as Yaw herself.

His name was Vere Goldthwaite, and as befits any star’s romance, the versions of it are many. One is that she was traveling in Montana when they met. He was a cowboy, barely literate, but he was smitten, and she told him he could write to her. Another is that they met aboard ship, no details about where or which ship. In a third, he rescued her from a flood, perhaps on horseback, and they fell in love. He went east, to study law, to make himself worthy of her. Summers off from law school, he joined the Buffalo Bill Wild West show, and traveled to London, where, what-ho, he ran into Yaw again. He gave up the gun-slinging showman’s life and returned to study law, passed the bar, and set up a practice. He was, The Times concluded, “picturesque.”

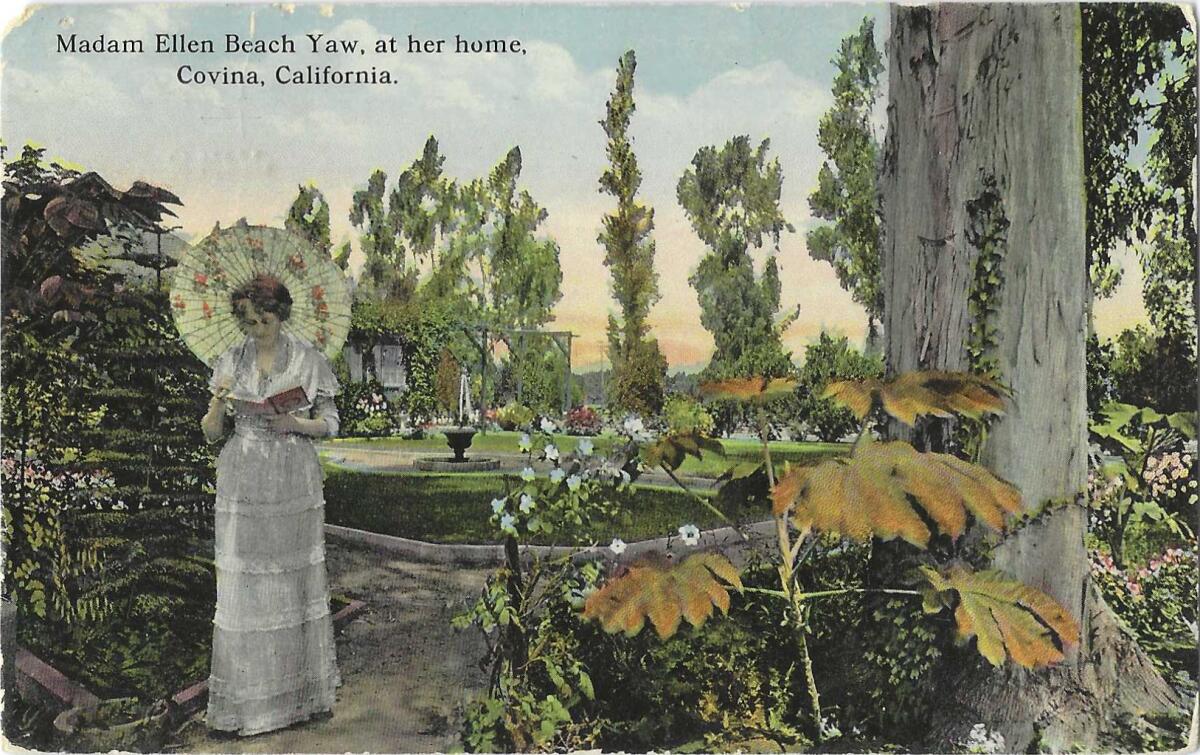

He gave up the law after their marriage to help manage her career. The couple rested between tours on their ranch in Covina, and Goldthwaite, dressed in khaki or corduroy, often spoke to the local farmers’ club — not just about farming but in passionate endorsement of women’s suffrage. In 1910 he made his own grand tour, crusading for the woman’s vote. He also wrote poetry. “Picturesque,” indeed.

He was about 40 when he died, in 1912.

Mourning, and then World War I, meant touring in Europe was out of the question. Yaw stayed closer to home, raising money for the boys’ home that bore her name, and for a day-care project that looked after children whose widowed mothers had to work.

She also taught singing to promising pupils, spoke and sang for high school music classes, and on her property built an impromptu amphitheater, an “echo bowl” that amplified her singing voice. In 1917 she ventured to Hawaii for a concert, and that same year sang at the funeral of her great promoter, Times publisher Otis.

Yaw’s second husband was a pianist, Franklin Cannon, 15 years her junior. They married in 1920, in a moonlight ceremony on the terrace of her Covina house, and they performed a song she wrote for herself, “The Skylark.”

The pair toured as a performing duo but divorced in 1935.

When she died, in 1947, the woman who had been front-page news for The Times was memorialized on Page 8.

Oh, and Taylor Swift? By most accounts, a mezzo soprano. Not breaking glass — just records.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.