Post-affirmative action, Asian American families are more stressed than ever about college admissions

- Share via

The admissions consultant described what it takes to get into an elite college: Take 10 to 20 Advanced Placement courses. Create a “showstopper project.”

Asian American students need to be extremely strategic in how they present themselves “to avoid anti-Asian discrimination,” the consultant, Sasha Chada of Ivy Scholars, said at the October webinar to an audience of mostly Asian parents and students.

Edward Yen, who doesn’t consider himself a “tiger parent,” wondered what extreme accomplishments his 11-year-old daughter will need to get into USC — considered a relative shoo-in back in the 1990s, when he attended.

“I appreciated the honesty,” Yen said of Chada’s presentation, which was co-hosted by the Los Angeles County Asian American Employees Assn. and the nonprofit Faith and Community Empowerment.

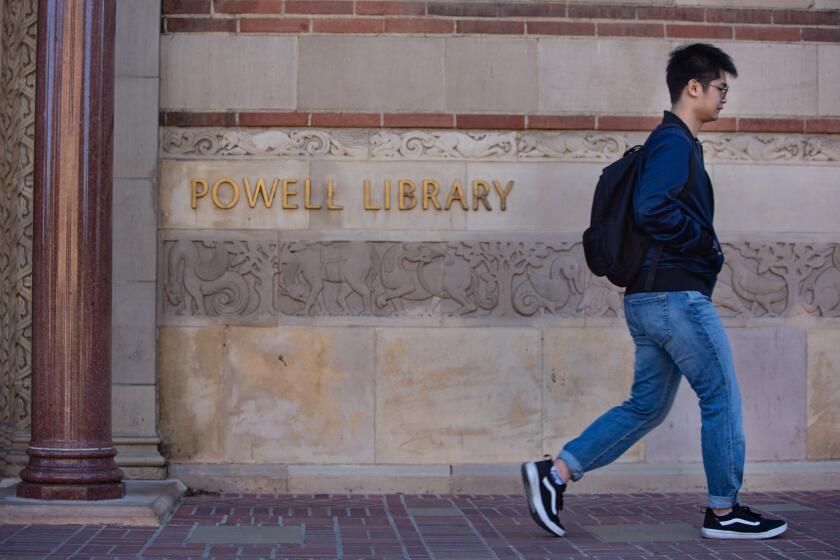

In the first college application season since the U.S. Supreme Court struck down affirmative action, Asian American students are more stressed out than ever. Race-conscious admissions were widely seen to have disadvantaged them, as borne out by disparities in the test scores of admitted students — but many feel that race will still be a hidden factor and that standards are even more opaque than before.

Some Asian Americans believe college officials will find ways to get around the ban and ensure they admit enough underrepresented students, including Black Americans and Latinos.

At seminars like Chada’s around Southern California this fall, some held in Korean or Mandarin for immigrant parents, consultants reinforced the message — even students with superhuman qualifications are regularly rejected from Harvard and UC Berkeley.

Parents who didn’t grow up in the American system, and who may have moved to the U.S. in large part for their children’s education, feel desperate and in the dark. Some shell out tens of thousands of dollars for consultants as early as junior high, fearing that anything less than a name-brand school could doom their children to an uncertain future. Sometimes, anxious students are the ones who ask their parents to hire a consultant.

Some consultants say they try to push schools that fit the student best, not necessarily the top-ranked ones — even as skeptics wonder whether they are scare-mongering in an attempt to drum up business. But especially for parents from countries like South Korea, China and India, where a single exam determines a student’s college choices, the lack of objective standards can be overwhelming.

“The worst part of stress comes out when kids feel helpless, not when someone sets a high bar for them,” said Chada, whose Indian father grew up in Northern Ireland.

Yen pointed out that going to a top college is no guarantee for career success, with Asian Americans overrepresented at many campuses yet underrepresented in leadership positions in government and other workplaces.

“A lot of our Asian parents are thinking it’s a golden ticket if you’re able to get into Harvard or Yale,” said Yen, president of the Los Angeles County Asian American Employees Assn., who lives in San Marino and whose parents immigrated from Taiwan. “I just want my daughter to be healthy, safe, and I want her to be successful in life.”

Srikanth Nagarajan, a 52-year-old manager at DirecTV and an immigrant from India, has been nudging his daughter to shoot for top schools like Harvard.

Sam Srikanth, a senior at El Segundo High, has a 4.41 GPA and has taken seven AP courses, which she said was the maximum number offered at her school. She is captain of the varsity swim team and is working on a research project about the role of race in college basketball recruiting.

After asking teachers and school counselors to read her admissions essays, Srikanth decided to hire a private counselor. But she ended up not using the counselor’s suggestions because they didn’t feel like her voice.

Srikanth said her “hopes got a little bit higher” after the Supreme Court’s decision.

But with her last name, she said, “you actually fill out the application and realize there’s no way colleges won’t figure out what race you are.”

The U.S. Supreme Court hearings on affirmative action this week highlighted widespread fears among Asian Americans that they face bias in selective college admissions.

Her older sister, who applied to colleges five years ago with a similar resume, got rejected from 18 of 20 or so schools and ended up at Boston College.

“I can’t be let down if my expectations are already so low,” Srikanth said.

When Sunny Lee came to the U.S. from South Korea in 2006 for postdoctoral work at USC, she thought that people could succeed in America even if they didn’t go to college.

But after moving to San Marino about a decade ago to raise her three sons — the oldest is now in seventh grade — she saw neighbors hiring athletic coaches and academic consultants for kids who were still in elementary school.

The moms she knows fret about students who seem like slam-dunks being denied by top schools.

“A student known as a genius at San Marino High ended up going to Pasadena City College,” said Lee, 48, a researcher at USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Moms were having a mental breakdown.”

A friend told Lee that she regretted spending only $3,000 for a consultant to go over her child’s admissions essays. For her next child, the friend would spend at least $10,000.

With both her and her husband working full-time, Lee feels an admission consultant is necessary just to keep up, especially with the opaqueness and unpredictability of college admissions.

“It’s a fight over information,” she said.

She said she doesn’t think her oldest son needs a consultant yet. But she would like her middle son, a fifth-grader, to start working with one.

Affirmative action’s end is celebrated by some Asian Americans, but what have we won? And what have we lost?

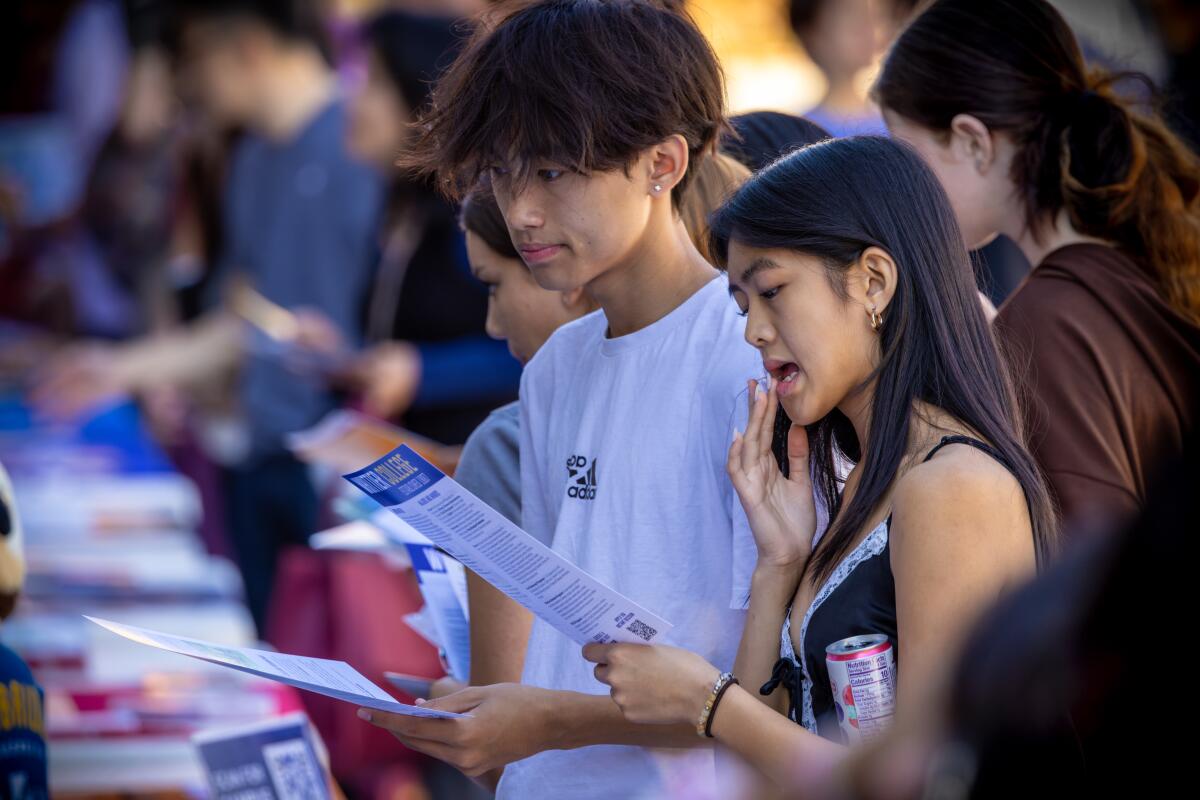

On the outskirts of Koreatown in July, dozens of Korean American students and parents attended a five-hour seminar hosted by Radio Seoul.

Several admissions consultants said in Korean and English that the end of affirmative action could improve Asian American students’ chances of getting into elite colleges.

One urged parents to give up their hobbies — no more golfing every weekend — so they can hover over their children.

Won Jong Kim, director of the college consulting firm Boston Education, described several students who got into elite schools.

Anna, who got into Harvard, took AP Calculus AB in seventh grade. Ben, who got into Stanford, took 15 AP classes.

Esther’s academics weren’t “stellar,” Kim said — only a 4.3 GPA, 1520 SAT and nine AP courses. But in her personal statement, she wrote about her mother’s fight with breast cancer. And she was admitted to the University of Pennsylvania.

“That was her trump card. It was a unique situation that she overcame,” Kim said. “To be frank, she got really lucky.”

In an interview, Kim said he wanted to show the “common characteristics” of those who get into Ivy League schools.

“Every year, the bar goes up for students looking to get into top colleges,” he said.

Research shows that for most people, admission to the most selective colleges has no significant effect on achieving their dreams.

Chung Lee, the chief consultant at Ivy Dream, said he tries to share information in free seminars hosted by various community organizations.

“The colleges’ lack of transparency has created this sense of fear,” he said.

In Temple City, Shun Zhang said she doesn’t want to put pressure on her son, Connor Sam.

Zhang, a 48-year-old real estate agent, wants to give him the support structure she didn’t have growing up as an immigrant from China.

Her only requirement is that he play a sport, to stay active and healthy. Still, Sam, a senior at Temple City High who is on the varsity soccer team and interns for Assemblymember Mike Fong, feels the need to push himself. He wants to double-major in sociology and some kind of science at UCLA.

Hoping to be “more organized and put together,” he asked his parents for a personal admissions counselor to help him reflect on his accomplishments and brainstorm essay topics. He has been working with the counselor for two years and finds it helpful.

Sam, whose father is a refugee from Vietnam and works as a project manager, said he thinks about how well his parents have provided for him and wants to be as successful.

Going to a good college would go a long way in securing a good job and “maintain where I am,” he said.

But for all his hard work and preparation, he views college admissions as a crapshoot.

“I don’t really know what they are looking for,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.