- Share via

SACRAMENTO — In his tan suit and gold tie, Jarad Nava blends in easily at the California Capitol, as though he’s always belonged to its mahogany and rose-hued halls.

But underneath the button-down shirt — unseen and unimaginable to those who don’t know his story — tattoos evoke his former life: on his arms, the name of a park his gang claimed as territory, rolling dice and an inked-over “P” that had represented Pomona; on his chest, flames licking up the base of his neck.

Just a few years ago, Nava was serving a 162-year sentence for a crime he committed when he was 17.

Now 28, the young man who once thought he’d never see the outside of a prison works as an assistant for the state Senate Public Safety Committee, an influential panel of lawmakers who review legislation related to the criminal justice system.

The irony is not lost on Nava, who eventually won his freedom by learning to atone and accept, truly accept, responsibility for what he had done. It required disciplined work, a newfound faith and, as Nava put it, serious reflection on what “led to me shooting at a car with four people in it.”

An uneasy childhood

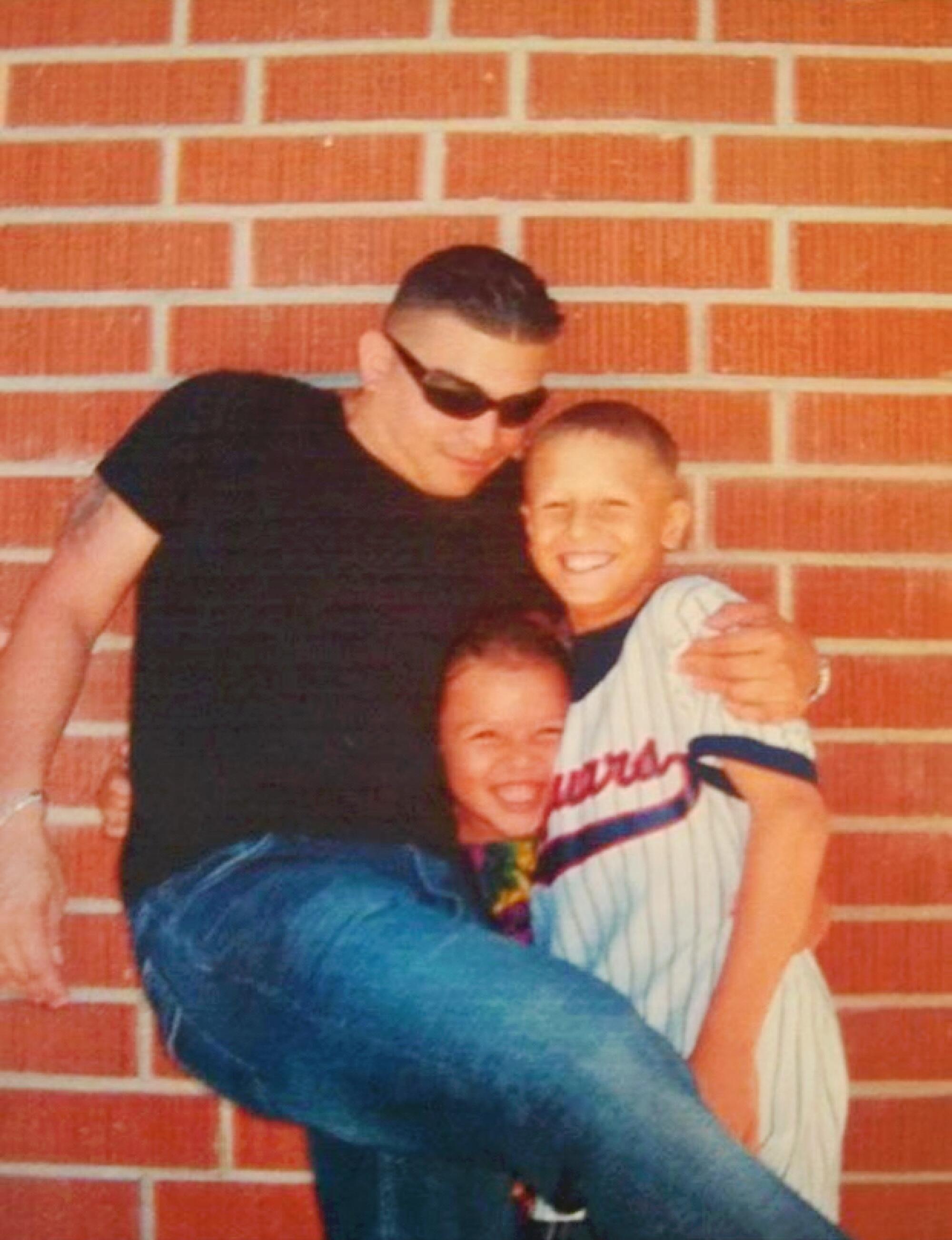

As recounted by Nava and in legal documents, he was born to a struggling 19-year-old mom and absent dad in the summer of 1995 in Battle Creek, Mich. When he was a toddler, his mom uprooted them to Washington state, where she joined the Navy and met his stepfather, who became the boy’s role model.

The family relocated to Pomona and grew to include three younger sisters. But given financial and other pressures, they never stayed anywhere for long, pingponging around Southern California and back to Michigan.

Nava said he liked school, at first, and excelled in math. But the transfers to a dozen or so schools between kindergarten and fifth grade made academics difficult.

“It felt like there was no stability,” Nava said.

The one place he felt indomitable was playing center field and catcher in Little League. Baseball, he said, “was like my identity.” On the field he earned the praise and validation he craved at home, where his family was slowly falling apart.

His world collapsed when, at 11, his parents said they couldn’t sign him up for another season. Nava figured the family would work it out, as they always had, but the season came and went without him.

“Now reflecting back I can see, oh, they just couldn’t afford it,” he said.

His sense of security continued unraveling alongside his parents’ marriage.

He remembers waking up one evening when he was around 13 to yelling coming from the garage, where he found his mom screaming as his stepdad attempted suicide by taking a knife to his stomach.

The family never talked about it, but Nava remembers that night as the moment he lost faith in his hero and stopped being a kid.

His parents divorced before he reached high school, and Nava split his time between them — again hopping from home to home.

With little interest in school, but with a work ethic he’d later come to be known for in the Capitol, Nava took after-school jobs selling newspaper subscriptions and random stuff — gummy bears, jumper cables, candles. He graduated to selling coupon books, making up to $200 a day, and later started his own clothing company.

At one point, Nava moved into a friend’s house and rented a room for $500. He dropped out of high school, then moved back in with his mom at 16 and enrolled in a continuation school to get his diploma. But their relationship was strained, and the living situation was rocky.

“I didn’t know how to be a kid, basically,” he said. “I felt like I didn’t really have family or anything.”

So he reconnected with some old friends.

Joining the gang

It started with petty crimes, breaking into cars, vandalizing buildings and getting into fights.

At a time when “so much in life felt so powerless,” Nava said, the Pomona Don’t Care Krew, or DCK, felt like a real family.

DCK was a “tagging” crew, or a fledgling gang of younger members who typically go on to join a more established and violent group. Nava was “jumped in” to DCK at 16, feeling as though he had recovered that “purpose and identity” he last experienced on the baseball field.

As Nava became more determined to prove himself, his criminal behavior escalated. He started drinking, smoking weed, carrying a gun.

“The more violent you were, the more you felt like you were respected or feared,” Nava recalled. “In order to protect myself, I felt like the more I perpetrated violence on others, the safer I would be.”

The more violent you were, the more you felt like you were respected, or feared.

— Jarad Nava

The evening of Sept. 29, 2012, in Pomona was a violent one.

A monthlong dispute between DCK and its former allies in the Cherrieville gang had intensified, and gunfire broke out at least four times. One shooting happened near Nava’s apartment complex, where he lived with his mom and little sisters.

The last incident, just before 11 p.m., occurred at the intersection of Glen and Orange Grove avenues.

Nava said he doesn’t remember much of what happened when the white truck he was riding in swerved into the opposite lane and pulled alongside a Lexus sedan carrying what he thought were his enemies.

In the car were Yesenia Castro, 16; her sister Marlene Castro, 15; Jessila Suarez, 25; and Marlyn Reyes, who was 17 and nine months pregnant.

The Castro sisters had an older brother in Cherrieville, and Suarez and Reyes were dating two brothers in the gang.

Nava was high and drunk. He doesn’t remember telling the four, according to court records, they were “gonna die today” before he fired multiple rounds into the car.

Suarez threw herself over Reyes to protect the baby. A bullet grazed Marlene’s left leg. Yesenia was shot in the back. As they raced toward the hospital, Yesenia wasn’t breathing.

“Her eyes were rolling back” and she was bleeding, Reyes testified. Marlene had thrown her shirt over her sister to soak up the blood.

The bullet severed her spinal cord, paralyzing her from the waist down. With Yesenia still in intensive care, the Castro sisters picked Nava out of a six-pack of photos detectives showed them.

Nava said that his memory of the days after the shooting is foggy, but that he had nightmares and was paranoid about someone breaking into his apartment, about getting shot.

He was home with friends when, six days after the shooting, police surrounded the apartment, calling his name over loudspeakers. He stepped outside to surrender.

Before hauling him off to the station, Nava said, officers told him to enjoy his final touch of grass.

During an interrogation, Nava confessed and asked what would happen next.

“Probably going to get charged with attempted murder,” a detective said.

“Attempted murder? That’s life?” Nava asked. “How much time do you think I could get?”

Attempted murder? That’s life? How much time do you think I could get?

— Jarad Nava, to a detective.

It was a juvenile case, the detective said. Prison time could vary. “I’ve seen everything from 10, 15, 20 years to life,” he said.

Nava was charged with four counts of attempted murder, one count of shooting at an occupied motor vehicle and, after detectives found a gun in his apartment, possession of a short-barreled shotgun.

He declined a plea deal of a 30-year prison term and stood trial as an adult, which California allows for 16- and 17-year-olds as a way to keep those convicted as older teenagers in custody beyond the age cap of 25.

“I didn’t take the plea deal at the time because I was still not taking responsibility for what I had done,” he said recently. Also, for a teenager, three decades behind bars “felt like life.”

“So it was like, how much worse could it get?” he said. “Obviously, it got a lot worse.”

Standing trial

The trial began in January 2014 in Pomona.

The young women recounted the gunshots and frantic rush to the hospital.

Nava was found guilty on Feb. 7 and, three months later, sentenced to 162 years in prison: 40 years to life for each attempted murder charge, plus two years for the shotgun possession.

At the sentencing hearing was Alex Sandoval, who drove the car the night of the shooting. Unlike Nava, Sandoval took a plea deal and received 30 years for similar charges.

After Nava was sentenced and taken into custody, Sandoval had his own chance to apologize to the victims. He also begged for leniency for his younger friend.

“I don’t really think that Nava should — you should have mercy on Nava,” Sandoval told the judge. “He’s young, really intelligent. I don’t believe he should have life.”

The judge noted that Sandoval, with his guilty plea, had taken responsibility for his actions. “I think that is why you are going to have a life after state prison, unlike your friend, Mr. Nava.”

After Nava was convicted, his victims addressed the court. One after the other, each offered forgiveness.

“They changed my whole life. It’s a struggle now. But, yeah, I forgive them,” Yesenia Castro said of her assailants, adding that she had since given birth to a daughter. “But all I got to say is I hope everything goes good for them. I don’t have nothing against them.”

Marlene Castro, Reyes and Suarez did not respond to requests for comment. Yesenia Castro, speaking through her screened front door in her wheelchair, declined to be interviewed.

Headed to prison

By late 2014, Nava had been sent to Ironwood State Prison in Blythe.

He was 19 and at a crossroads.

“It was just kind of like a realization, you’re never going home,” he said. “At that point, that’s when I was faced with the question of what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

Some months earlier Nava had read a self-help book and undertook an exercise to write down the names of everyone he had harmed. It was a long list. He dredged up memories of fistfights, teasing classmates and stealing someone’s scooter. He wrote an apology for every offense.

Then he wrote the names of everyone who had caused him harm, a list almost as long as the first. And he forgave them all.

“After doing that whole process, there was just an immense sense of peace that overwhelmed me,” he said. “Running from it was exhausting. ... To face it within myself was just extremely impactful.”

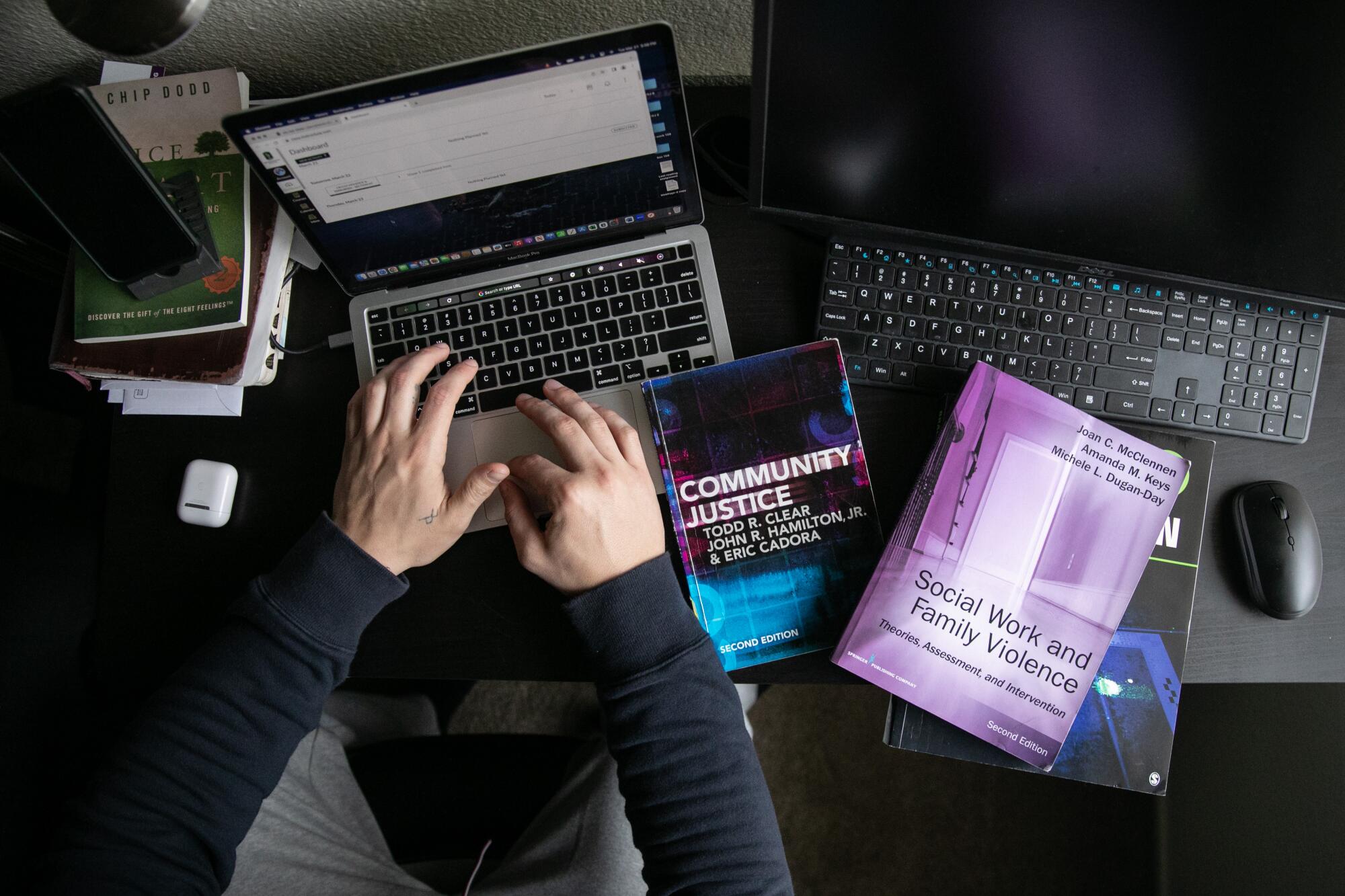

Nava enrolled in college courses and joined every program he thought could propel his life forward: Narcotics Anonymous, Alternatives to Violence, emotional intelligence courses, a writer’s workshop and a class called Criminal and Gang Members Anonymous. He joined the Prison Walk-A-Thon to raise money for cancer, worked as a peer educator and learned Braille to translate college textbooks for the blind. He earned his GED diploma, then an associate’s degree in business and technology.

He also reflected on how his victims had forgiven him at his sentencing. “As I got older and I really understood the gravity of what I had done … I’ll say that it was extremely humbling that somebody who had experienced such a wrongdoing could find it in their hearts to forgive me in that moment.

“The best way to describe it is I feel undeserving of that,” he said.

Nava did not have a religious upbringing, but in prison, he said, he gave his life to Jesus. He found comfort in church services, where he’d worship alongside the mentors and friends he made in prison. Once more, he’d found what started to feel like family.

“It was a lot of love,” he said.

He saw the work to improve himself as restitution, a way to make spiritual amends for a crime that left Yesenia Castro dependent on a wheelchair.

But his efforts gave something he never expected.

A chance for freedom

In 2018, lawyers at the Juvenile Innocence and Fair Sentencing Clinic — encouraged by film producer Scott Budnick — took interest in Nava’s case.

While in juvenile hall, Nava had met Budnick — a producer of the “Hangover” films and founder of the nonprofit Anti-Recidivism Coalition — who was teaching a creative writing class.

Budnick also helped produce “They Call Us Monsters,” a documentary that featured Nava and two other teenagers in a film-writing class who were being tried as adults.

“He was dynamic, personable, challenging, a handful, just like a little bit of a wild kid,” Budnick said.

“But you know when you see that spark, and you know when someone is remorseful, and you know when they have some of those core qualities that can make them very successful? I saw all of that in him,” Budnick said.

Christopher Hawthorne, director of the clinic at Loyola Law School, saw the documentary and believed Nava had been poorly represented at trial. But Hawthorne wasn’t shocked by the long sentence.

“We were still in the middle of the super predator panic,” Hawthorne said. “There was a sense that Pomona in particular was awash in gang activity.”

(The documentary includes Yesenia Castro, who, despite her comments of forgiveness in court, said she wished Nava would serve a long sentence.)

Hawthorne figured that Nava had matured since his time in juvenile hall.

“I was confident that when I met Jarad, he would be different. And he really was,” Hawthorne said. “He was well-spoken, thoughtful. He understood what he had done.”

Hawthorne and others at the clinic put together a clemency application that demonstrated Nava’s rehabilitative work in prison. They gathered support letters and cited legal cases on juvenile brain development.

They also laid out his life story: He was born to a teen mom and had already been exposed to gang culture in the neighborhood and witnessed gun violence by age 6. He witnessed his stepfather’s suicide attempt and was bounced from household to household. As a lonely kid, he joined a gang to “escape the turmoil of his life at home.”

At the end of 2018, the clinic shipped Nava’s application off to then-Gov. Jerry Brown. Nava went through an initial interview, the start of the process toward a Board of Parole Hearings session. And then he waited.

The clinic had asked that his sentence be modified to 15 years to life. In March 2020, the new governor, Gavin Newsom, commuted Nava’s sentence to 10 years to life.

“This act of clemency for Mr. Nava does not minimize or forgive his conduct or the harm it caused,” Newsom wrote. “It does recognize the work he has done since to transform himself.”

Six months later, Nava went before the Board of Parole Hearings — a panel of attorneys, psychologists and former corrections officers and wardens — and recounted how he’d used his time in prison to work on his “character defects.”

Recalling the 17-year-old who opened fire with a gun, he told the board, “I felt at that time that I didn’t have any friends. I didn’t have nobody to, uh — I, I didn’t feel like I had any family.”

If released, he said, his plan was to enroll at Sacramento State to study computer coding. But backup options were getting into electrical work, applying to Caltrans or an Amazon warehouse, or if all else failed, making hamburgers at Carl’s Jr. because the restaurant chain hires those with felony records.

Nava said he had Budnick to lean on for support, along with his faith and the friends he had made at church.

During the hearing, he apologized to his victims, to their families, to his family, to the city of Pomona, to the hospital workers who cared for the Castro sisters.

“I feel deeply ashamed about what I did.”

I feel deeply ashamed about what I did.

— Jarad Nava, to the parole board

Los Angeles County Deputy Dist. Atty. Leslie Hanke argued against Nava’s release, saying that he was still “impulsive and reckless” and hadn’t demonstrated adequate remorse or empathy for his victims.

The commissioners took a break to deliberate and in nine minutes reached their decision: Nava did not pose an unreasonable public safety risk. He was suitable for parole.

A second chance

Newsom upheld the board’s decision, and Nava walked free from California State Prison Solano more than 150 years early on Dec. 22, 2020, with little more than a Sacramento State acceptance letter and a ride from Budnick to California’s capital.

Budnick also helped Nava get settled in his new home in Sacramento and search for work. He introduced Nava over FaceTime to Erika Contreras, the secretary of the state Senate and a fixture in the Capitol.

Contreras, who for much of her career had worked on criminal justice policy, told Nava there was an internship available at the Capitol. Why not apply? The work included handling Employment Development Department cases for workers who’d lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. He got the internship.

“He was an incredibly great listener, very empathetic,” Contreras said.

Nava later transferred to the Senate Transportation Committee, at which he earned a reputation in the Capitol as a hard worker, and then landed a coveted job with the Senate Public Safety Committee.

He is one of many former prisoners whom the Legislature has included in discussions over how to modify the criminal justice system in California to focus on rehabilitation in lieu of lengthy prison terms.

This year, formerly incarcerated people have come to Sacramento to support bills that would overhaul solitary confinement rules, allow prisoners to vote and prohibit forced prison labor.

The trend is reflective of California’s decadelong effort to shift away from “tough-on-crime” policies toward a system that promotes prevention and rehabilitation.

“To be able to properly focus on which policies are important to let people start their life again, you need the input and viewpoints of those individuals that have been part of the process,” said state Sen. Aisha Wahab, a Hayward Democrat and chair of the Public Safety Committee.

Nava “has worked so hard to turn his life around, so hard to stand on his own two feet, so hard to really say, ‘I’m interested in doing more,’” Wahab said. “He has so much potential, and that’s the thing about human beings. We are not to be judged by a single action. We have an entire life that we need to consider, and the potential good that is possible from every individual.”

Nava’s role doesn’t include influencing policy or crafting legislation. But his presence is a reminder of the importance of the committee’s work, said Mary Kennedy, chief counsel of the panel and Nava’s boss.

“As a group, we’re supportive of people being rehabilitated and working after they’ve come out of prison,” she said. But Nava’s presence turns the abstract into flesh and blood, a reminder that policy “affects people.”

A new life

A decade later, Nava resembles the teenager who once thought he’d never touch grass again. He’s grown a goatee and added muscle to his frame, but still has the same laugh and sincere smile of his adolescence. He’s fluent in policy talk, street-accent style.

He’s not taking any of his new life, his second chance, for granted.

“I feel so grateful to be in the building,” Nava said. “When I wake up and I go to work, I love it.”

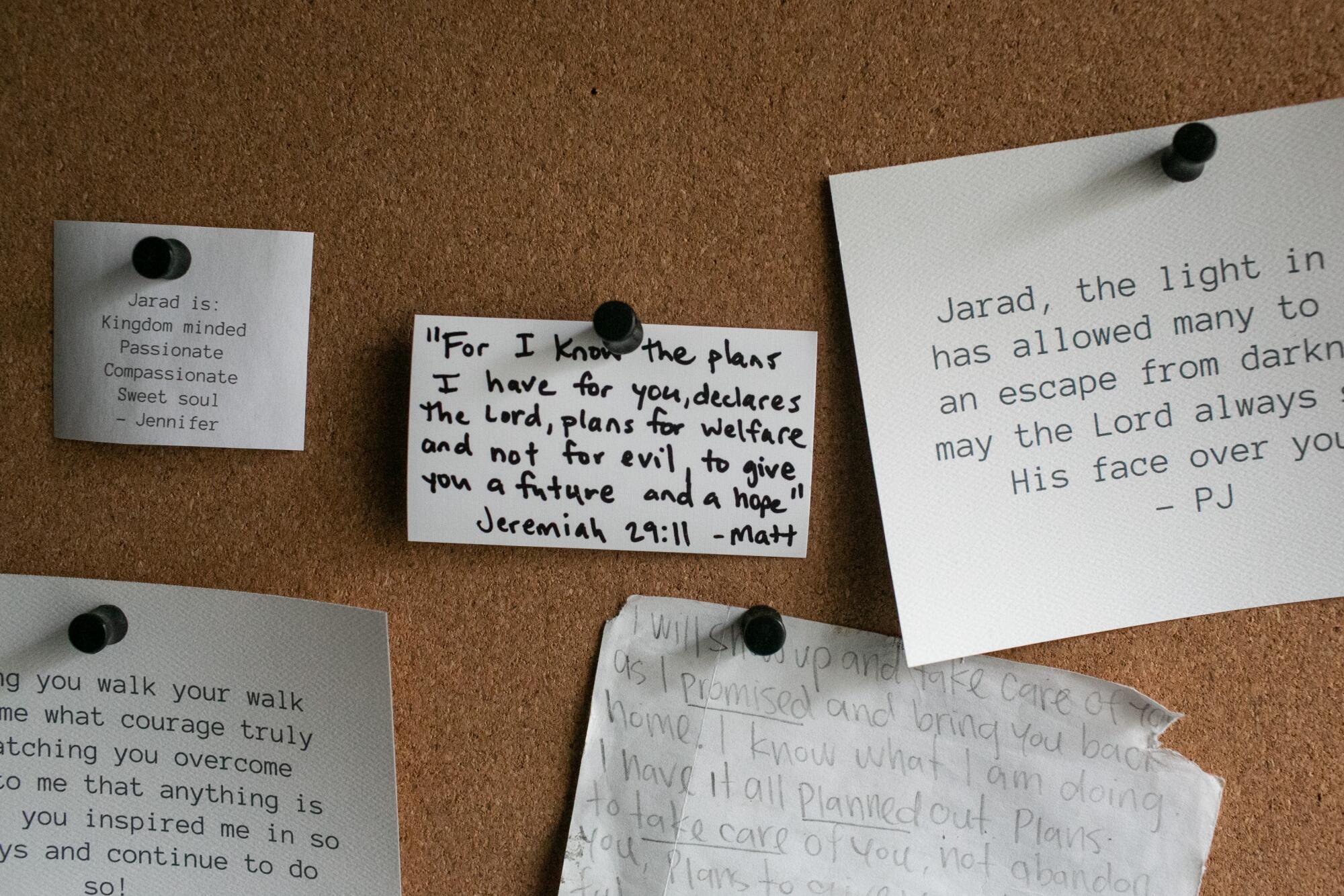

He keeps a large binder of his parole hearing documents tucked away in the bedroom of his Sacramento apartment.

In it is a relapse prevention plan, letters of support from loved ones and, somewhere in between, a copy of an apology letter he wrote to Yesenia Castro but has not mailed because he believes he should not intrude on her life.

“I want to say I’m sorry for trying to murder you on Sept. 29, 2012. … You should never have had to experience being shot, and I thank God you survived,” the letter says. “Though I can never fully atone for my actions, I will spend the rest of my life trying.”

Nava also has hung a picture of him with Newsom.

Recalling when he first met Nava in Sacramento last year, Newsom said: “I came back and started crying in the office. To read a report about somebody, to see a ridiculous overcharging, to consider his age in relationship to that crime, to take a risk on a commutation … and then to see him all dressed up, so proud that he has a job. And I remember that meeting because he kept talking about how he felt a sense of responsibility not to screw up. Not for himself, but for others.”

Nava sees his work at the Capitol as a way to fulfill that promise.

On the hard days, he turns to his favorite Bible verse for some hope. Romans 12:2:

Be no longer conformed to this world. But be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is that good and acceptable perfect will of God.

When Nava completes his work for the day, he attends night classes in criminal justice at Sacramento State. He’d like to stay in public policy. Perhaps he’ll keep working for the Public Safety Committee.

Either way, in the California Capitol Jarad Nava is finally home.

Editorial assistant Nicholas Perez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.