California to step up efforts to find boxers owed pensions following Times report

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Leer en Español

California is overhauling the nation’s only pension plan for retired boxers following a Times investigation that found the safety net for vulnerable fighters is failing its most critical mission — informing those owed benefits.

The California State Athletic Commission, which administers the little-known 40-year-old pension plan, said it will begin sending annual statements to all vested boxers beginning early next year and that it has brought in state investigators to search for fighters with unclaimed money — some of whom have been owed for decades.

Roughly 200 boxers could have claimed a pension last year, but only 12 of them (6%) did, according to The Times’ investigation.

- Share via

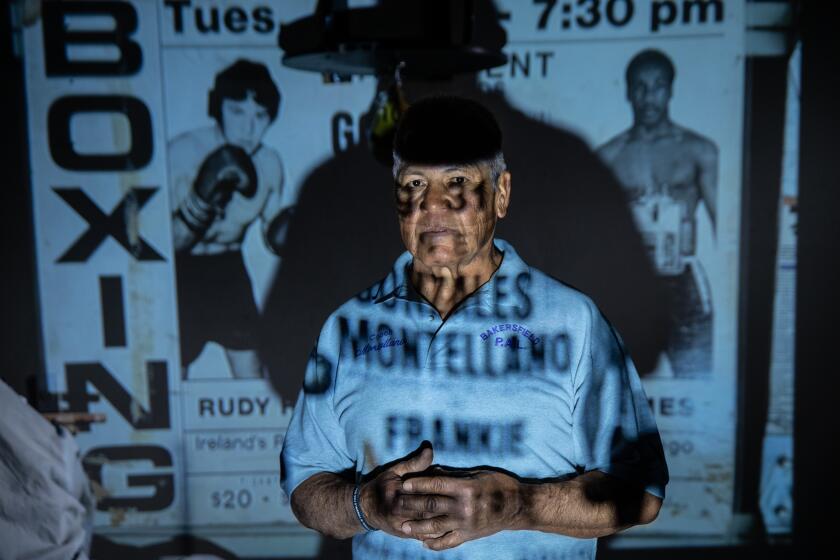

Hector Lizarraga qualified for the California Professional Boxers’ Pension Plan. It’s the nation’s only state-administered retirement plan for fighters. He’s using the money to invest in his backyard gym.

More than two dozen retired boxers owed pensions told the paper they could not recall ever receiving information from the commission informing them that they qualified or how to apply. They knew little about other benefits of their pensions — such as the ability to withdraw money early to pay for medical expenses or vocational education.

Some, like heavyweight journeyman Mike Jameson, said they had never heard of the California Professional Boxers’ Pension Plan, which is paid for through a fee on ticket sales to boxing events.

“I don’t want to browbeat them, but they could have done a much better job letting people know,” said Jameson, a 68-year-old retired boxer from San Jose who first learned he was owed a pension from The Times. “It’s great to hear they are going to do more.”

Jameson applied for his benefits in April and last week received a $12,000 check.

State Assemblyman Matt Haney (D-San Francisco) said he was alarmed to read The Times’ story and immediately called the athletic commission to ensure changes were made not just to the boxers pension, but also to a bill he is authoring to create a similar retirement plan for mixed martial arts fighters.

Boxers contacted by The Times said they were unaware that California has a 40-year-old pension program or that they are its beneficiaries.

Haney amended Assembly Bill 1136 to require that the commission send annual statements informing future vested MMA fighters of their account balances. The Assembly unanimously approved the bill Wednesday and it now moves to the Senate.

“The boxers’ pension is critical, but it can be improved,” Haney said in an interview outside the Assembly chambers. “I hope that as we move this MMA pension bill through the process, we correct some of the challenges that exist with the boxers’ pension and don’t replicate them — and that we also fix it for boxers as well. We have to let folks know who qualify and we have to make sure they can access it, otherwise this isn’t going to work.”

The MMA bill notes that as a group, professional athletes in combat sports may end up injured, destitute and suffer “extraordinary disabilities” as a result of their profession, including “acute and traumatic brain injuries, resulting from multiple concussions as well as from repeated exposure to a large number of sub-concussive punches and kicks, eye injuries, including retinal tears, holes and detachments, and other neurological impairments.”

If the bill becomes law, the commission would adopt regulations determining how many fights would be needed to become eligible for the MMA pension. Haney said he expects fighters would become vested after 12 to 14 fights in California.

California’s pension for boxers was created in 1982 and provides mostly lump-sum payments to fighters who have logged at least 75 scheduled rounds in California without more than a three-year break. The amount a boxer receives is based on how many rounds they fought and the purse for those bouts.

Once a boxer turns 50 and is eligible to apply for their pension, the amount they are owed is set and does not increase. Retirement plan experts said that means the longer it takes a boxer to claim their pension, the more it diminishes in value due to inflation.

Currently, the boxers’ pension pays an average of $17,000 in a lump-sum payment to retirees, according to a Times’ analysis of commission records.

The boxers’ pension plan began making payments to eligible boxers in 1999 and, to date, has provided 235 retired fighters a total of $4 million. Most of that has been paid in the last decade. However, an additional 200 boxers are owed pensions and have not claimed them.

“They never said anything about it when I was a pro,” said welterweight Mike Dallas Jr., 36, of Bakersfield, who retired from boxing in 2020.

The California State Athletic Commission struggled for years to contact boxers who were eligible for pension money. We found some in minutes.

That left him unsure if he qualified for a pension. The commission verified to The Times that Dallas has a pension, which he can claim when he turns 50.

Dallas learned from a Times reporter that the plan allows boxers as young as 36 to withdraw all or some of the money they’ve accrued to pay for vocational education.

“I could have used that when I was going to trucking school,” Dallas said.

He said he recently learned his father, Mike Dallas Sr., is owed nearly $13,000 in benefits. Dallas Sr., who fought as a lightweight, died in 2012 from leukemia at 45. Dallas Jr. said his dad likely never knew he had a pension, which was eligible to be paid to his family immediately after his death.

“I never knew about it, nobody did, not my dad, not anyone,” said Dallas Jr., who plans to file a claim for his father’s pension.

Retirement planning experts said a pension plan structured like California’s should mail annual statements as soon as a person is vested to ensure recipients know about their benefits and can plan for their future. It also ensures the plan has regular contact with its beneficiaries.

However, the athletic commission has waited until a boxer turns 50 before attempting to contact them for the first time. By then, the vast majority of addresses on file are decades old.

In response to The Times’ story, the commission will begin sending statements when a boxer first meets minimum requirements for a future pension and then every year thereafter. That change is expected to begin early next year, said the commission’s executive officer, Andy Foster.

The agency is also now using the Department of Consumer Affairs’ Division of Investigation to obtain up-to-date contact information for boxers with unclaimed pensions, said Foster, who also plans to hire a private investigator to locate additional fighters.

California owes benefits to about 200 boxers through the California Professional Boxers’ Pension Fund. How to claim a California boxers’ pension.

The commission is in the process of posting a new licensing application that includes a pension acknowledgment form that boxers sign as a way of ensuring new fighters know they are automatically enrolled in the plan.

Over the past decade, the commission has, on average, paid 15 boxers each year. So far this year, the commission said it has sent pension checks to 10 boxers. Another three will be paid once the commission transfers funds to pay them, while four others are in the process of filing paperwork.

The Times spoke to several others who said they plan to file for their newly discovered pensions in the coming weeks.

Foster said he has set a goal of providing benefits to 50 boxers this year — which would double the number of boxers paid in a single year, according to commission records analyzed by The Times.

“I’m just trying to get people paid,” Foster said. “If they are owed money, get them paid.”

The pension plan, however, has a rocky history of generating adequate revenue and it does not have enough money to pay all of the boxers who can claim a pension now without reducing what others receive in the future.

The plan set aside only 14% of the $2.1 million needed to pay boxers with late claims — which includes those who have not filed for their pension before turning 54.

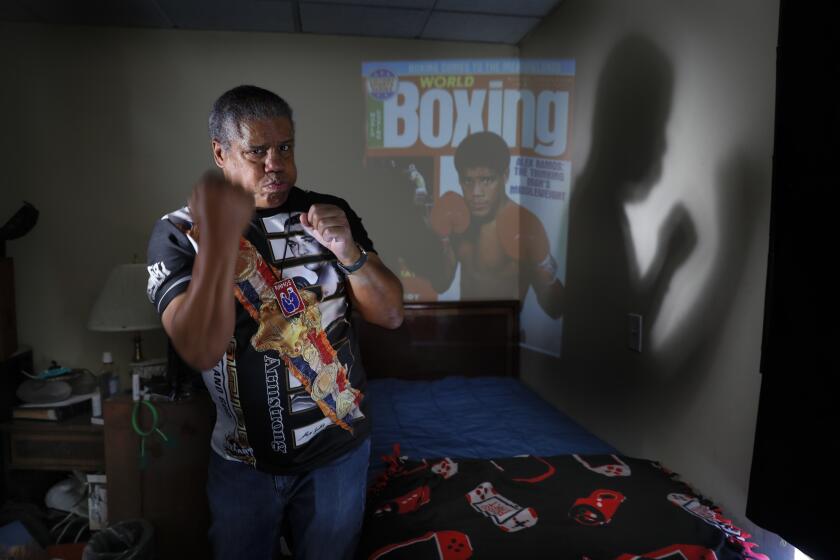

Alex Ramos started a foundation to help struggling boxers after retiring. But he has been unable to tap a California pension program to assist with his own needs.

If the commission has more late claims than funds available, it would reduce the amount of money in the accounts of fighters who are not yet 50.

Foster downplayed the impact of a large number of boxers applying for their pensions at once.

“If you’re in your 30s and you’re vested, you may see some decline,” Foster said. “It might happen, but the market will probably go up and they will see it back.”

The commission is looking at additional revenue sources for the boxers pension and is planning to raise its 88-cent ticket fee to $1 in the coming months, Foster said.

The MMA pension bill calls for that plan to be funded with a ticket fee — expected to be set at $1 — at those events and souvenir sales. At its board meeting next week, the commission will discuss a plan to pursue additional funding for both pensions by creating a specialty license plate, which has generated millions for other state programs.

Haney, the lawmaker carrying the MMA pension bill, said he would like to see the boxers’ and MMA pension plans provide an annual check that can better aid fighters in retirement.

“Many of these [MMA] fighters would qualify for it 20, 30 years from now, so we have some time to get this right,” Haney said. “In the case of the boxers’ [plan], we have to fix the flaws.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.