He’s accused of killing her brother in Davis. Why she forgives him

- Share via

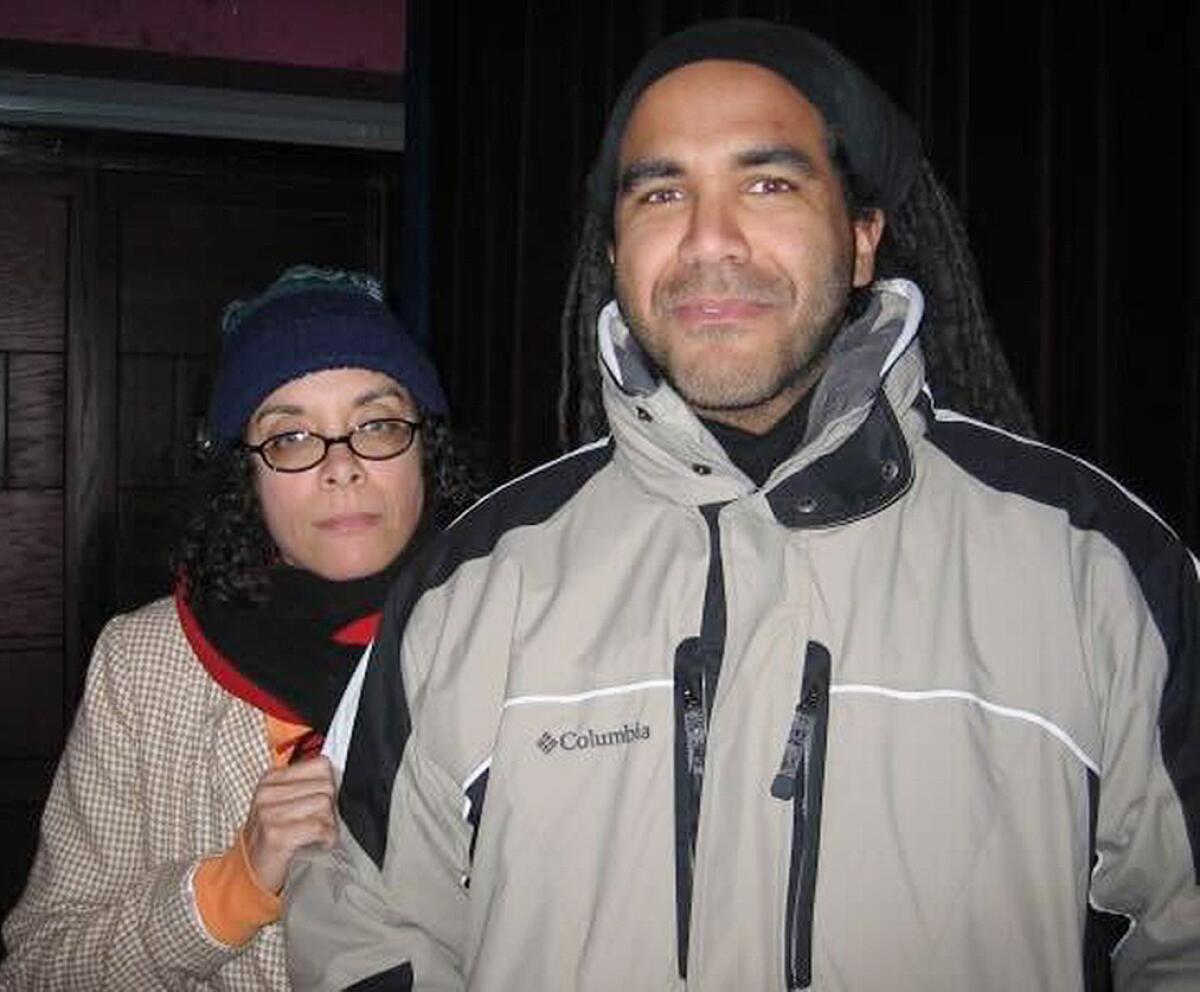

DAVIS, Calif. — David Breaux knew his life on the streets put him at risk, so he left his older sister explicit instructions.

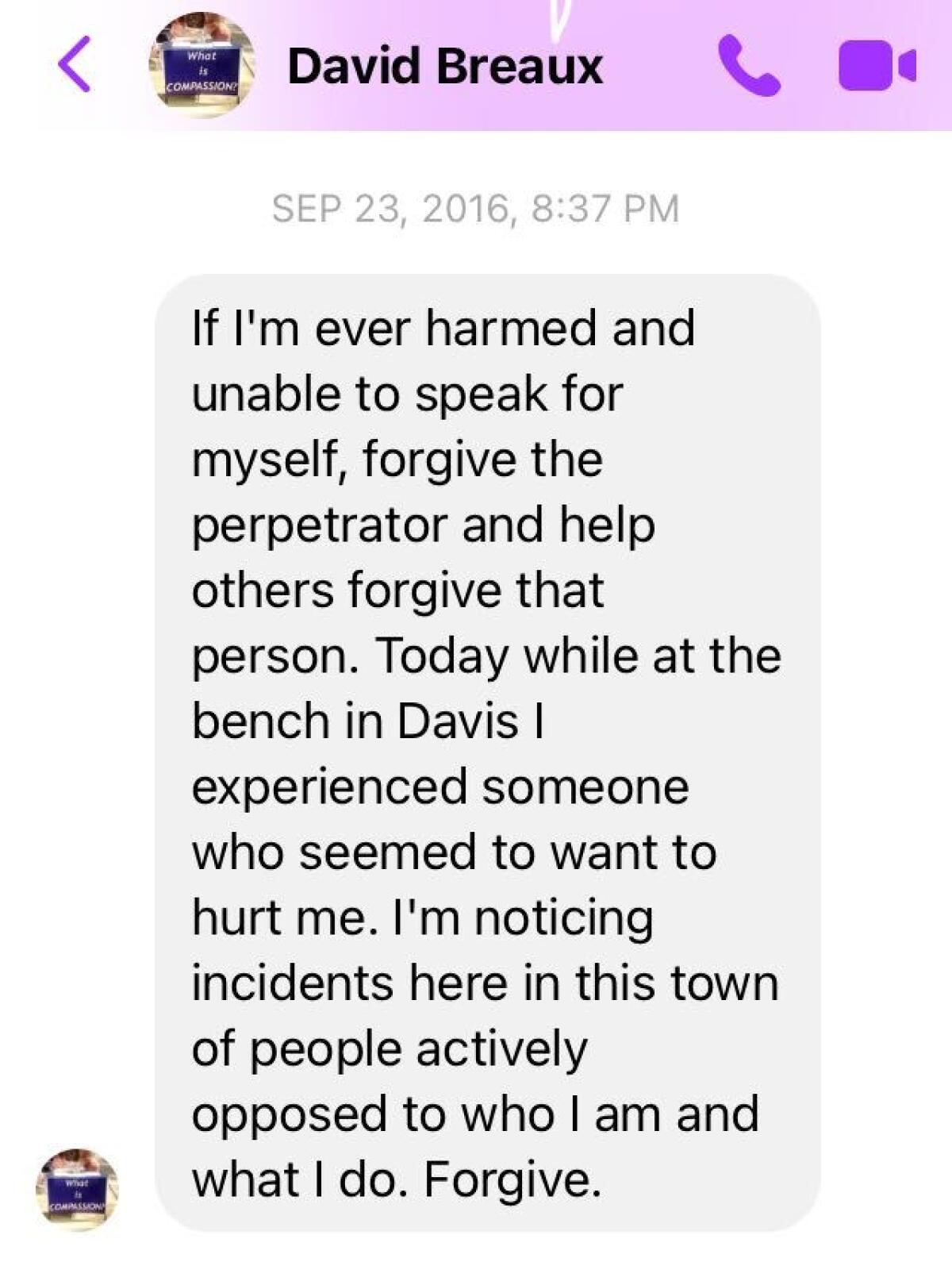

“If I’m ever harmed and unable to speak for myself, forgive the perpetrator and help others forgive that person,” he wrote in a 2016 Facebook message.

The ultimate test of forgiveness came April 27.

That’s when Breaux’s body was found stabbed on the bench where he often slept in Davis’ Central Park, a tree-lined gathering spot for families and students in this bike-friendly college town. Carlos Reales Dominguez, a 20-year-old who had been kicked out of UC Davis for academic reasons two days before, stands accused of Breaux’s murder.

Two nights later, according to police accounts, Dominguez fatally stabbed another resident, UC Davis student Karim Abou Najm, 20, as he biked home from a university event where he had received a research award; two nights after that, Dominguez allegedly attacked a homeless woman in her 60s as she slept in her tent near railroad tracks not far from downtown. She survived the stabbing, with the help of fellow campers, and is recovering from her wounds.

Dominguez, charged with two counts of murder and one count of attempted murder, has pleaded not guilty and remains in custody in Yolo County jail as his case proceeds.

For the families and friends of the two men killed in the seemingly random attacks — Breaux, a gentle man of 50 who preached a gospel of compassion, and Abou Najm, a computer science whiz known to be brilliant and kind — the journey ahead will be less about the legal proceedings and more about how to continue after such a crushing, senseless loss.

Losing a loved one to violence is a unique form of trauma, setting off waves of suffocating anguish. Some who are left behind find themselves consumed with anger or a thirst for revenge. Others are flattened into a paralyzing numbness. And some get to work, trying to raise meaning from horror.

After her brother’s death, Maria Breaux was quick to realize her path forward. It was what he would have wanted.

“I have to start the process of forgiveness,” she said this month by phone. “That was just something that came into my mind. I thought also this person must have been in such pain to have gotten to this point to do this. Either they’re in great pain or having some kind of mental break, or someone has failed them, or maybe we’ve failed them.”

In the well-kept home they shared with their son, where his shouts of laughter would waft down from his second-floor bedroom as he chatted with friends over Discord, Abou Najm’s parents do not want to talk about the perpetrator or whether he should be forgiven.

They intend to follow the legal case but have dedicated themselves to efforts to make sure their son’s short life has a lasting impact. They’ve started a scholarship in his name. They’re working with the city of Davis on a memorial in Sycamore Park, where he was killed. And, in conjunction with UC Davis, where both parents work and their son was set to graduate early, they plan to organize initiatives for research into mental health and better interventions to help people before they commit terrible acts.

Nadine Yehya, Abou Najm’s mother, said her son was above all full of care for those around him. “And I think, as a community, this is what we need more of,” she said. “It’s care, right?”

::

In the days after Breaux’s death, many in Davis posted his quote about forgiveness to their Facebook profiles. The sentiment ignited a powerful debate about the human capacity to forgive.

“He was a wonderful man and this quote puts his kindness on full display, but I can honor and acknowledge his feelings without making them my own,” wrote one Reddit commenter.

Another, who attended high school with Abou Najm, was more blunt: “I don’t feel an ounce of empathy or compassion for this KILLER!! As for David, I highly doubt he meant to forgive a murderer. He probably meant forgive someone who harassed and hurt him, not murder him.”

It is impossible to know for sure. But it’s clear that Breaux, who made such an impression on the Davis community, had developed an unusual capacity to relate, accept and forgive.

According to his sister and his own writings, Breaux and his two siblings grew up in suburban Duarte, at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. Their mother struggled with schizophrenia, and their authoritarian father routinely whipped his children as a form of discipline and hit his wife as a form of “medical treatment.”

“I am pressed to remember a conversation between my father and I lasting longer than a minute during those years,” Breaux wrote in a 2016 Medium post.

Breaux’s mother died while he was at Stanford University, where he got a degree in urban studies. His father, by then old and frail, asked Breaux to return home after graduation to help out. He did.

In the Medium post, Breaux describes becoming his father’s caregiver, shopping for groceries, paying bills, doing the cooking. He writes about seeing his dad differently: “No longer seeing him as a role. As a father. As a tyrant. As a dictator. As an abuser. No longer seeing him as anything other than … A human being.

“Forgiveness is being at peace with the past. I know I could never do what I do today as a figurehead for compassion if it were not for forgiving my father,” Breaux wrote. “I always suggest to those who come to me asking about forgiveness to do it before someone passes.”

Breaux, who stood tall at 6 feet 2, landed in Davis in 2009 and became a fixture at the corner of Third and C streets downtown, asking people to share their concept of the word “compassion” in his many notebooks. He collected thousands of responses and eventually published a book on the compilation. He was informally dubbed the “Compassion Guy” and garnered a following in Davis and beyond.

In a 2010 short film, “Standing Compassion,” Breaux talked about his conscious decision to live light, giving away his clothes and car. He decided, he said, “to spend a significant amount of time and energy directed toward a selflessness.”

In 2013, he worked with the Davis community to erect a bench at Third and C, decorated in bright ceramic tiles that celebrate the value of compassion. He interviewed visitors about their views on empathy as part of a weekly YouTube series.

When Maria learned in 2019 that her younger brother was sleeping outside, she came to offer help.

“He reassured me he was fine and that he was living in a state of pure love and compassion, and 100% here and now in a mindfulness sense,” she recalled.

Maria invited her brother to stay with her in San Francisco, where she worked as a senior copywriter and filmmaker. But he declined. When a mutual friend offered him an extra room in his Sacramento house, Breaux again said no.

Maria’s 2019 visit was the last time she saw him alive.

In the weeks since her brother’s death, Maria, 54, has been working to channel his light spirit and to draw on forgiveness in her search for resolution. When she learned that the person accused of killing her brother was just 20, a third-year student majoring in biological sciences before UC Davis “separated” him for unspecified academic troubles, and a dutiful son and brother, she thought, “Something doesn’t compute.”

“What is in this person’s heart that someone wasn’t able to touch?” she asked herself. “And can someone touch that in him so he doesn’t have to suffer for the rest of his life?”

Cloaked in an anti-suicide vest, the young suspect charged in a spate of brutal stabbings in Davis pleaded not guilty Friday.

Maria thought of her mother’s mental health struggles. She recalled a time as a teenager when her mother — who she knew loved her deeply — came into her bedroom with a knife and spoke quietly of needing to kill her. Her mother just stood there as Maria reasoned with her, until her father saw what was happening and took his wife out of the room.

Maria sat down to write a note to the parents of Dominguez, the young man accused in her brother’s death, assuring them that she forgave him and hoping that he and his family “can heal from all of this.”

“That’s their son, and that’s a child,” she said, her voice choked with tears. “That’s someone who they had in their lives until he went to college.”

Maria said she has avoided looking at comments about the stabbings on social media, knowing that others “have their own process.”

“People grieve in their own ways, and they express fear in their own ways, and I have great compassion for that too,” she said. “For me, the greatest healing has been through forgiveness.”

::

Abou Najm’s friend Aman Ganapathy is on a different emotional journey.

“I can’t think about him or talk about him,” he said of the suspect. “I try not to.”

Yehya, Abou Najm’s mother, expressed a similar sentiment.

“Karim’s family does not want to give any space or attention to the perpetrator. He already took the most precious thing from us,” she said.

What they do want to focus on is Karim. The way he seemed to turn everyone around him into a better person, simply by believing in them, as Ganapathy put it. About his irrepressible sociability. The way he would convert strangers into friends, drawing them out of the pandemic isolation that characterized his first years on campus. His mother marveled at a photograph of her son on an Amtrak train to Portland, Ore., where he managed to befriend fellow passengers on a journey of less than 20 hours.

Friends and family spoke of his infectious passion for computer science and a voracious intellect that made room for serious discussion on a range of topics, from “The Lord of the Rings” to French existentialism.

They recalled his enviable energy — as evidenced by the time a few months ago when he declared, “Bro, I wanna be ripped,” then followed up by joining a gym and working out every single day.

In Davis, Calif., a town that usually bustles with bikers and joggers on almost every street and path, its parks bursting with the sights and sounds of youth sports, city life is suddenly eerily quiet after a string of stabbings.

His father, Majdi Abou Najm, said he and his wife return to the place where their son was killed every day, sometimes twice a day. A shrine has sprung up, bursting with flowers and notes. They collect the notes and study each one. Again and again, they find a similar story: how their son reached out to someone and made a connection.

They have been astonished at the breadth of tributes. From classmates. From friends in Beirut, where the family lived before coming to UC Davis for jobs. From baristas at the coffee shops where their son studied — and chatted and chatted — on a nearly daily basis.

After a childhood that took his family from Nigeria to Indiana, Lebanon and finally Davis, Abou Najm was adept at making friends. He loved to debate and was ferociously good at it. His parents would not have been surprised to see him become a lawyer or a judge. Instead, he fell in love with computer programming and was working on a device to use virtual reality to make a better hearing aid.

As they reel from heartbreak, his parents said, they have become sure of something else: Their ordeal would be far worse without the support of the community that has enveloped them. Within hours of their son’s death, friends and family were at their side. So much food came that they couldn’t possibly eat it all, and friends took to Facebook to find places to donate it.

And so, as they mourn their son, they have committed themselves to improving their community in his name.

The ideas have risen up, one after another. The scholarship. The focus on mental health. A memorial in the park where he died.

They have transformed even the worst, most shocking moment — the conversation with first responders who knocked on their door to inform them that their son was dead — into a proposal for how to do things better.

“We are working with the town on revising the grieving and trauma protocols,” Abou Najm’s father explained. Typically, he said, a caring person knocks on the door, delivers the thudding news, then retreats to give the family space. But the family believes “space is the worst thing for many people.” Instead, he said, grieving relatives should be given the option of having someone stay with them. He hopes the model will be adopted in Davis and eventually across the country.

The parents seem hollowed out by their loss. In photos of them with their son and daughter, who is 12, they wear joyful smiles. But in their living room, sitting beneath a photo of Abou Najm and a framed copy of his UC Davis diploma, their faces are etched with pain.

Still, when they talk about all the ways they will make the world better in his name, there is a clear sense of purpose.

“As his parents, we miss his presence immensely,” his mother said. “But we are energized to make out of this tragedy something good to the community.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.