- Share via

Were it not for his sister’s killing, Roy Rodriguez might have left Camarillo.

Rachel Zendejas was sexually assaulted and slain in the small, sleepy city in Ventura County in 1981, her naked body found across the street from the apartment she shared with Rodriguez. Every year on Jan. 18 — the anniversary of her death — Rodriguez made the solemn call to detectives, asking for updates and begging to continue the search for her killer.

He kept calling long after the case went cold. His parents died without any answers. His brother too. Rodriguez could not move away. He wondered whether the killer lived in the area or was someone he knew.

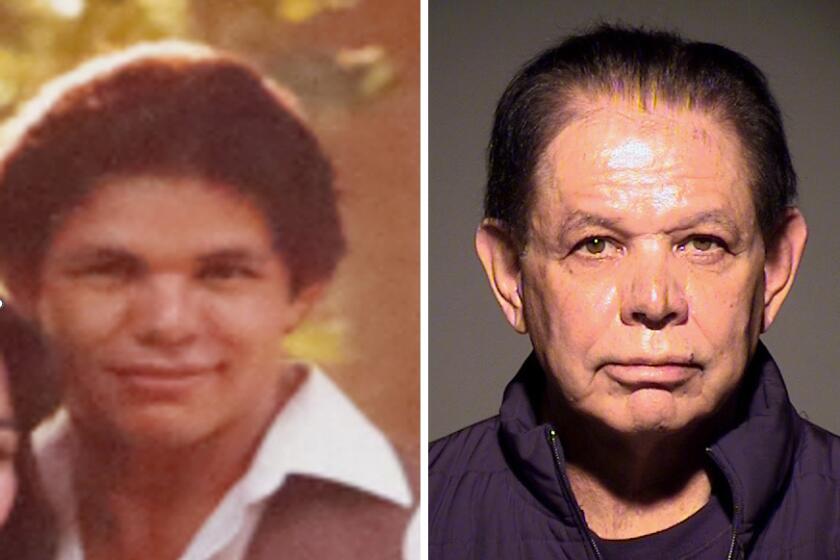

Now, 42 years after her killing, police say the man who ended Zendejas’ life was close at hand for all those years. Tony Garcia, a children’s karate instructor, was arrested Feb. 9 in Oxnard, about 10 miles from where Zendejas’ body was dumped.

The 68-year-old Navy veteran was charged with murder not only in Zendejas’ slaying but also in the death of another woman, Lisa Gondek, the same year.

“It’s just like she died all over again,” Rodriguez said. “It just makes you wonder if we ever were in the same place. ... He was hiding in plain sight. We used to drive by that karate place all the time.”

While prosecutors have not provided a specific motive in the slayings, Ventura County Deputy Dist. Atty. Richard Simon said Garcia — whom he called a “serial killer” — had been suppressing his violent tendencies.

“He’s been holding it in. The desires that he has, the urges that he has, have been held in for a long time,” Simon said in court.

Garcia has denied the charges, which include an enhancement for rape.

Tony Garcia, 68, of Oxnard was arrested Tuesday in the 1981 strangulation deaths of Rachel Zendejas, 20, and Lisa Gondek, 21, authorities said. One woman was sexually assaulted.

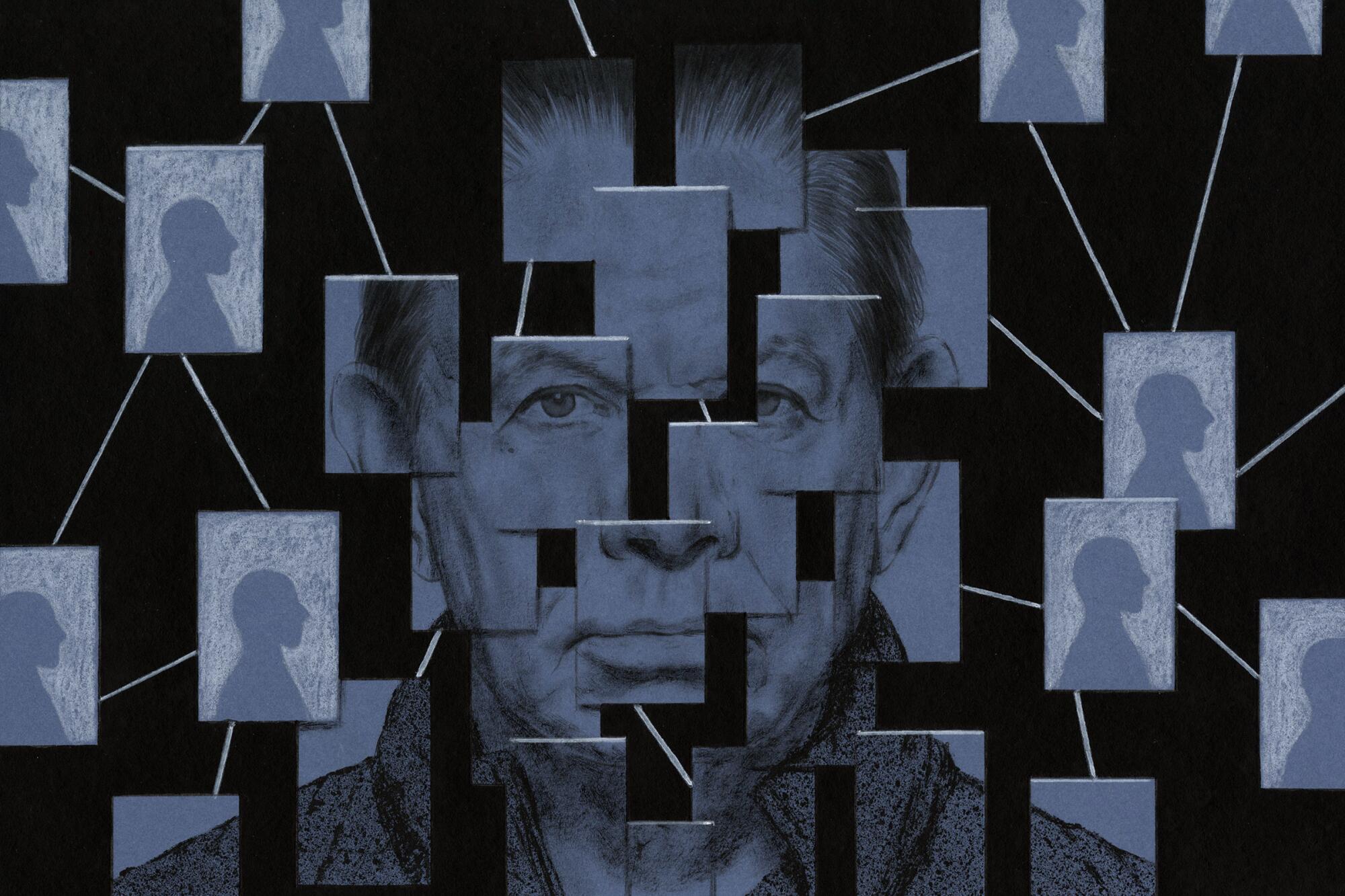

The search for Zendejas’ and Gondek’s killer has been an odyssey spanning generations of detectives in Ventura County, one filled with starts and stops and a misstep based on junk science that left one man the top suspect for more than 20 years.

It also entails the continued emergence of DNA and investigative genetic genealogy, premier tools in cold cases that were once considered unsolvable. The approach injected fresh hope and energy into the investigation even as detectives combed through more than 150 years of ancestry data in search of their suspect.

Garcia seemed to have a quiet life.

The family man lived with his wife and son in a one-story house on a cul-de-sac in Oxnard. He taught at nearby Flores Bros. Kenpo Karate Studio , where he was a well-liked and affable instructor — jovial even, according to his students. He was a fourth-degree black belt. Photos from his Facebook show “Sifu Tony” smiling in his karate gi. One outside the strip-mall studio shows him with three young girls, his hand on the back of one child.

He’d come a long way since his youth in Roswell, N.M., where his foster brother Jack McKinley said Garcia played football and wrestled while living with a foster family. He served four years in the Navy in the 1980s, working as an aircraft mechanic based at Point Mugu.

He had a couple of run-ins with police — convictions for driving under the influence and arson as well as an arrest in 1982 for indecent exposure, according to Ventura County Sheriff’s Office records. But that was behind him.

So when police swooped in to arrest Garcia outside the karate studio in February, his co-workers were stunned.

“It was a shock to my system,” said Kimberly Serratos, who had been a sparring partner with Garcia since 2014.

She said Garcia was good with kids but a stern teacher who brought his military background to his role as an instructor. He had once had his own studio but came to Flores Bros. after a car crash in 2005 that left him with brain damage, Serratos said.

Garcia’s attorney, Brandon Sua, said his client was in a coma for 10 days — “near death” — and suffered “traumatic brain injuries.”

Jun Park, the owner of Yokozuna, a Japanese restaurant and sushi bar next to the karate studio, described Garcia as a “normal old guy.”

Every Tuesday and Thursday for 17 years, Park said, Garcia taught kids karate. Sometimes he and his wife would pop in for a meal.

But all along, prosecutors allege, Garcia was harboring a sinister secret.

Traces of DNA at two crime scenes and countless hours of investigative work led law enforcement to Garcia, who they say was a stranger to the women he has been charged with killing.

“I never in a billion years would think he would do anything wrong,” Lori Hendricks, a co-owner of the karate studio, told the Camarillo Acorn.

The killings of the two women in 1981 weren’t connected when they occurred.

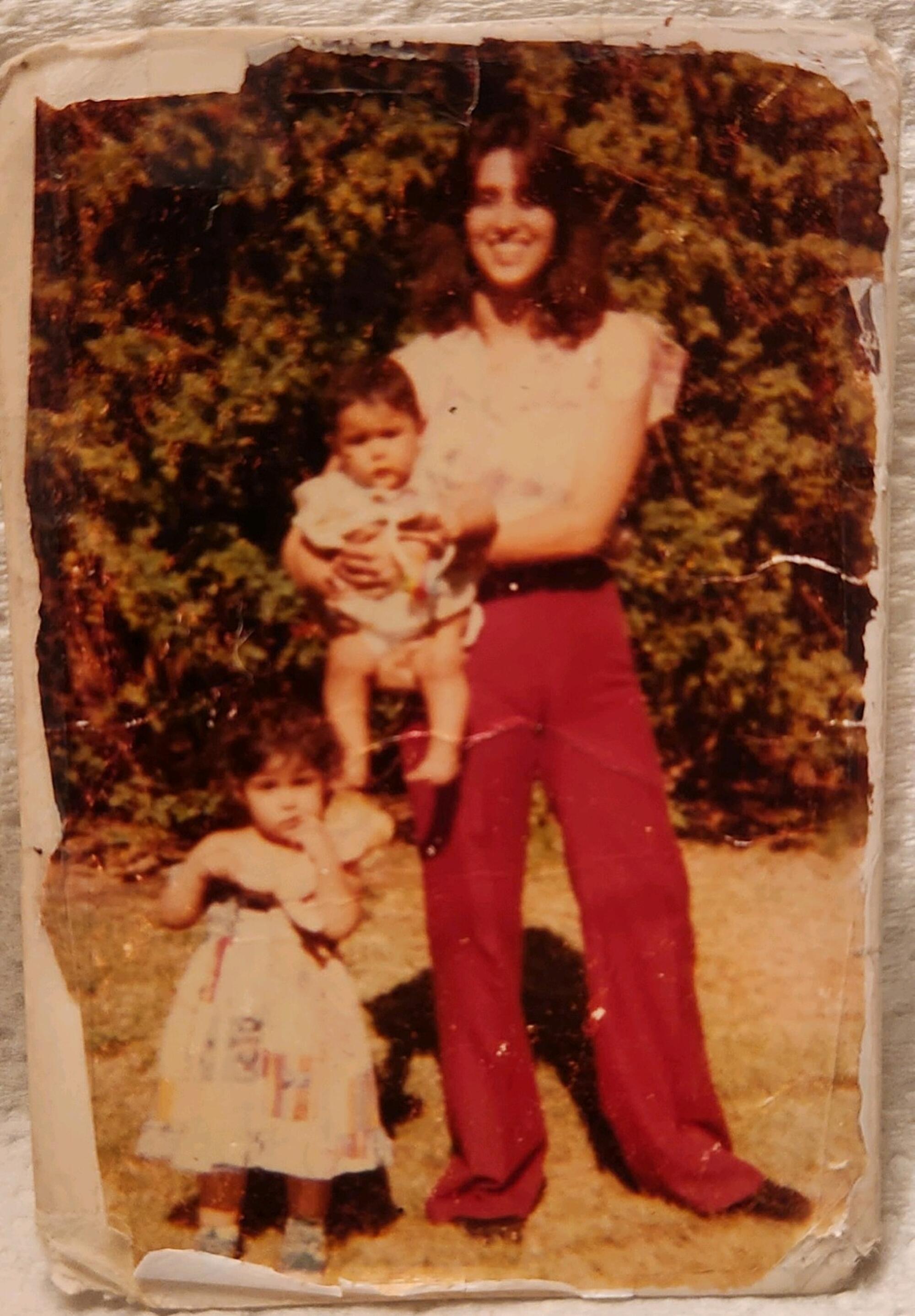

Zendejas was 20, a single mother of two toddlers living in Camarillo. She was studying industrial mechanics at Oxnard College and had moved into an apartment with her brother in late 1980 after she separated from her husband.

She and Roy Rodriguez had gone out for the evening on Jan. 17, 1981, to see their brother Mark’s band. Then Rodriguez went home while Zendejas continued on to a club called Huntington’s, he said.

“She came home slightly after me and the babysitters were there. And I could hear them talking, and I heard her yell, ‘I’m taking the babysitters home,’ ” Rodriguez said. “I woke up in the morning, she wasn’t home, and I was thinking, ‘Where’s Rachel?’ ”

He had no idea there was a crime scene across the street from his apartment complex. A woman’s nude body was sprawled next to a pole on Mobil Avenue. Police found a shirt and nylon leggings on a nearby patio. Car keys were uncovered in grass near the scene.

Zendejas had been sexually assaulted, strangled, dragged across the street and abandoned. Police said she had been attacked after dropping off the babysitters and parking her car back home. Her body was discovered by a pair of newspaper delivery boys.

But investigators had no leads, and as the years went by, the case grew cold.

“Year 3 came, and 4 and 5,” said Rodriguez. “I would call these TV shows, ‘Unsolved Mysteries’ and all that, but nobody would take the story.

“She was cheated out of life.”

Lisa Gondek, 21, was a transplant to Oxnard. She’d taken a bus from East Hartford, Conn., in May 1981, her parents told newspapers at the time.

The high school dropout worked as a hairstylist at salons in Connecticut, her parents said. After moving to California, she sold clothes in two local shops.

Like Zendejas, Gondek had gone out clubbing the night she was killed, police told news outlets. In fact, Gondek visited the dance club Huntington’s before catching a ride home with friends.

She was last seen talking to a male acquaintance outside her apartment complex around 1:50 a.m on Dec. 12, 1981.

Police and firefighters were called to her apartment about an hour later when an upstairs neighbor smelled smoke. The apartment had been set on fire, but the blaze hadn’t done much damage.

Gondek’s body was found in the bathtub with a bite mark on her cheek, according to police.

As in Zendejas’ case, authorities had little to go on. As the years went by, Gondek’s slaying became another unsolved homicide in Ventura County.

But nearly a quarter-century after the women were killed, a single piece of biological evidence linked their cold cases. After DNA profiling exploded in forensic investigations in the 1990s and 2000s, detectives discovered the same man had left DNA on each of the victims’ bodies.

The 2004 breakthrough helped lead to an arrest 19 years later — and helped clear another man long suspected in one of the slayings.

Two years after Gondek’s death, Oxnard police were confident they knew who had killed her.

They believed they had enough evidence to present the case to prosecutors, who would decide whether to bring murder charges against the suspect: the acquaintance last seen chatting with Gondek outside her apartment. The two had been dropped off by friends at her carport, where his motorcycle was parked. He said he watched Gondek walk inside.

Police believed the bite mark on Gondek’s cheek would identify her killer.

Her acquaintance, whom The Times is not identifying because he was never charged, voluntarily provided a dental impression, and forensic odontologist Dr. Raymond Rawson determined his teeth matched the mark on Gondek’s face. Two other odontologists were less sure, according to a 1983 report in the Hartford Courant, but police still believed they had enough evidence for an arrest.

But much to their chagrin and the frustration of Gondek’s parents, no arrest was made. Prosecutors with the Ventura County district attorney’s office declined to charge the suspect, saying there was not enough evidence.

“I personally went over it with [the deputy district attorneys], reviewed it and just concluded that it’s not a case that we should try or file,” said Michael Bradbury, the former Ventura County district attorney. “We thought [the suspect] probably didn’t do it.”

In 1983, bite-mark evidence — interpreted by forensic odontologists — was a growing field considered by many to be the cutting edge of crime-scene science. Media outlets wrote about odontologists like Rawson who “take a bite out of crime.”

But not everyone bought into it.

“We were pretty cautious about it,” Bradbury said about forensic odontology. “I had guys scratching their heads saying, ‘This is a little far out, boss.’ ”

The prosecutor said he was open to using bite-mark evidence at the time but would not use it as the sole physical evidence connecting a suspect to a crime — as in the Gondek case.

Rawson did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“It just makes you wonder if we ever were in the same place. ... He was hiding in plain sight.”

— Roy Rodriguez, brother of homicide victim Rachel Zendejas

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences found that bite-mark evidence was unreliable and suffered from “inherent weaknesses” because the arrangement of people’s teeth — or dentition — has not been proved to be unique. It also isn’t clear whether teeth marks retain any specific characteristics when transferred to human skin or other objects, the group reported.

More than 30 convictions based on faulty bite-mark evidence have been vacated, according to the Innocence Project, including the case of Ray Krone in Arizona. Krone spent more than a decade in prison on a murder conviction after Rawson testified at his trial that Krone’s dentition matched bite marks on a homicide victim. DNA evidence cleared Krone.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“Bite marks really are just total junk science,” said Chris Fabricant, the director of strategic litigation at the Innocence Project. “Forensic genealogy, on the other hand, is based on DNA evidence, which remains the gold standard.”

In 2004, Gondek’s acquaintance voluntarily provided DNA to be tested against the suspect DNA found at the scenes of the 1981 killings. It was not a match. After more than 20 years, he was eliminated as a suspect.

Still, it would be more than a decade before investigators found the method to unravel the mystery of the two women’s homicides.

Joseph James DeAngelo — the Golden State Killer — was caught using investigative genetic genealogy, a process by which researchers build family trees using DNA databases as well as traditional methods like newspapers and obituaries. DeAngelo’s arrest led law enforcement agencies across the country to turn to genetic genealogy to try to solve cold cases in which DNA evidence existed.

Steven Rhods was among those working the Golden State Killer case. When he was an ambulance driver in 1980, Rhods responded to a double homicide in Ventura that was the work of DeAngelo, who eventually admitted to 13 murders and more than 200 uncharged crimes of rape, assault and burglary in the 1970s and ’80s in California.

Later, as an investigator with the Ventura County district attorney, he interviewed DeAngelo in Sacramento and provided DNA samples from the 1980 scene, though he didn’t take part in the investigative genetic genealogy work that resulted in DeAngelo’s arrest.

But he learned how DNA databases could be leveraged to solve old cases.

After DeAngelo’s arrest in 2018, Rhods considered his own unsolved cases. He thought about Zendejas and Gondek, whose deaths were connected by matching DNA. In Zendejas’ case, the DNA was in semen collected in a rape kit. In Gondek’s, it was discovered under her fingernails.

“I thought this was one we could use it on,” Rhods said.

He and his colleagues got to work in December 2019. They had the suspect DNA in both cases sequenced and uploaded to GEDmatch, a public database where people can use their DNA to find relatives.

Although the suspect was not in the database, investigators discovered people listed as fourth cousins and began to build a family tree by searching for common ancestors between the suspect and his cousins.

Police and prosecutors are determined to access DNA information from private, consumer sites. They say the data is invaluable, but privacy advocates say the practice is ripe for abuses.

“We went back to the 1800s and built forward,” Rhods said. “We went down a lot of rabbit holes.”

As part of the investigation, detectives visited people potentially related to the suspect and collected more than 20 DNA samples to help determine whether they were on the right path, Rhods said.

One person who provided DNA proved to be a close family member of the suspect, Rhods said.

Finally, after consulting with FBI genealogists, investigators focused on a man named Jose Encarcion Garcia, who was born in 1856. The suspect in the slayings of Zendejas and Gondek was believed to be his descendant, Rhods said.

Detectives had certain parameters to help narrow their search. They believed the killer was a man who in 1981 was 17 to 41 years old. They also believed he or a relative lived in Ventura County and likely had a military connection. (There were two military bases in the area at the time, and Gondek had visited the Port Hueneme naval base the day of her killing.)

Investigators discovered Casmiro Garcia, a man from Roswell, N.M., who had seven children, five of them boys. One had joined the Navy — and was assigned to Point Mugu in Oxnard in 1981.

His name was Tony Garcia.

Based on Garcia’s background and his military station in Ventura County at the time of the killings, Rhods was “97% sure” he’d found his suspect.

The karate studio where Garcia worked was less than a mile from where Gondek was slain. To get to work from his home in Oxnard, he would likely drive past the scene.

But without Garcia’s DNA, detectives couldn’t determine whether he matched the suspect’s genetic profile.

Investigators set up a surveillance team and followed Garcia, hoping he would toss a smoked cigarette or some other evidence they could easily swab for DNA. He didn’t.

“It appears all he did was go back and forth between home and work,” Rhods said.

Eventually, a search warrant to test Garcia’s car door was issued. While he was in the karate studio, investigators swabbed the handle of Garcia’s 2006 Honda, Rhods said.

The DNA from the car door came back as a mixture of two males, both of which matched the suspect, Rhods said. Though the double match was initially concerning, authorities said it was likely because Garcia’s son had also touched the vehicle.

“That was enough to get a warrant for confirmatory DNA,” Rhods said.

The investigator and an arrest team headed to Flores Bros. Kenpo Karate Studio around 9 a.m. Feb. 9.

Rhods said he and his partner approached Garcia and asked whether he knew Gondek or Zendejas. Garcia said no, according to the detective.

“I walked away, and the arrest team went in,” Rhods said.

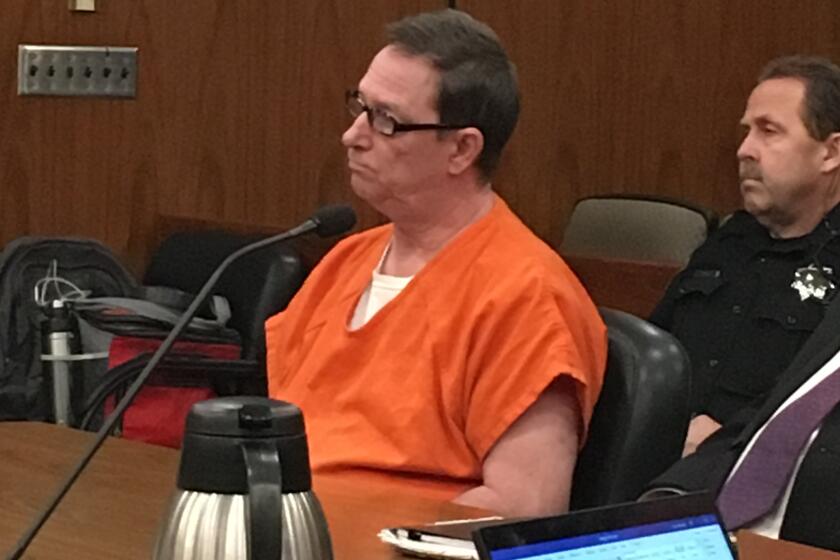

Garcia has pleaded not guilty to both murder charges and is being held without bail at Todd Road Jail in Santa Paula.

Sua, Garcia’s attorney, said his client “maintains his innocence,” though he did not provide a defense argument or alibi. Garcia’s wife, who declined to comment to The Times, and his son are standing by him, Sua said.

“He’s been holding it in. The desires that he has, the urges that he has, have been held in for a long time.”

— Ventura County Deputy Dist. Atty. Richard Simon

The attorney noted that prosecutors turned over evidence showing there were “multiple” other suspects who had been investigated.

At a recent bail hearing, Sua said Garcia has “extremely tight ties to the Ventura area” and is not a flight risk. He added that Garcia was not a danger to the community but a “skinny” and “frail” grandfather.

Prosecutors fired back. “Today he’s a grandpa, but he’s the most dangerous grandpa there is,” Deputy Dist. Atty. Simon said.

In a three-hour interview with Rhods after his arrest, Garcia did not admit knowing the victims. He could not explain why his DNA was at the two crime scenes.

For the D.A. investigator, the most satisfying part of his job is informing the families of homicide victims that a suspect has been captured. Rhods was there when detectives told Rodriguez that Garcia had been arrested in his sister’s case.

But he is not resting on his laurels. In Ventura County, there are 25 unsolved slayings with suspect DNA from crime scenes. The county also has more than 3,000 untested rape kits.

Rodriguez intends to see the case to its close. He attends each court hearing and visits his sister’s grave in Camarillo frequently to lay flowers or just sit and spend time near her.

“I want justice for my sister,” he said. “And I want him to pay for it — for destroying our family and taking my nieces’ mom away.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.