- Share via

When California enacted landmark criminal justice reforms several years ago, inmates and their families saw a chance at freedom.

Aaron Spolin saw a business opportunity.

After the laws went into effect in 2019, the then-33-year-old attorney incorporated a law firm in West Los Angeles and began marketing legal services to the incarcerated and their loved ones.

Spolin, a Princeton-educated former McKinsey consultant, bought up online search terms so that people googling the laws saw ads touting the firm’s expertise. He mailed pitch letters directly to some of the state’s 100,000 prisoners introducing himself as a former prosecutor now “in the top 1% among California criminal lawyers” and informing them they might be eligible for “sentence shortening under various new laws.”

Nearly 2,000 individuals signed on with Spolin, according to the online resume of a former office manager. He became a celebrity inside prisons, his name passed around in exercise yards from Folsom to Calipatria, and in Facebook support groups for wives and children. Families of limited means borrowed against their homes, took out high-interest loans, dipped into 401(k)s, worked double shifts, ran public fundraisers and amassed credit card debt to pay Spolin fees that could run north of $40,000.

A Times investigation found that Spolin built a booming enterprise by fanning false hopes in some families desperate to get their loved ones home. He encouraged people to spring for pricey legal services that he knew or should have known had little or no chance of success, the newspaper found.

Aaron Spolin advertises himself as ‘California’s top-ranked habeas attorney,’ but The Times found that his firm failed to conduct the work required.

He told families of men incarcerated for murder and other violent crimes that progressive L.A. Dist. Atty. George Gascón could move to free them in less than a year under one new resentencing law. None of Spolin’s attempts, for which families paid about $10,000 each, appear to have been successful, and Gascón’s office told The Times it generally does not consider such offenders to be good candidates for resentencing.

In another example, Spolin presented a commutation from the governor, which experts say is a long shot for even the most rehabilitated of candidates, as “a very real possibility for all types of inmates.” Hundreds paid up to $14,000 for him to submit applications. None has been granted, The Times found, and some were patently unsuitable. One inmate he proposed for commutation this year had pleaded guilty in May 2022 to running a drug ring from his cell at Corcoran State Prison.

The Times found that Spolin’s firm relied on the work of some low-paid contract lawyers who were not licensed in California and had little or no experience in criminal appeals. Among those helping draft legal memos and court filings were lawyers from the Philippines and other developing countries making about $10 an hour.

Spolin denied exploiting inmates and their families and blamed district attorneys’ offices and others who he says have taken too narrow a view of which individuals should be freed.

Stephanie Charles, an actor whose brother, Wesner, has been behind bars since 2002 for robbery and attempted carjacking, said she now worries the $19,000 she and other loved ones scraped together to pay Spolin for a commutation and other services was wasted. “A lot of us don’t know the law, a lot of us are vulnerable,” she said. “We just want someone to help us solve the problem and not take advantage of us.”

Supporters of the state’s criminal justice reforms are among Spolin’s biggest critics.

“This guy is getting rich off the most vulnerable people and [giving] them false hope that could really hurt them. It needs to stop now,” Karen Nash, a deputy L.A. public defender who represents prisoners seeking resentencing under the reforms, wrote in a January email to the State Bar of California.

The new laws are designed so that prisoners who qualify get free legal representation.

“It wasn’t contemplated that this would become ambulance chasers who would see this as a way to make money off the backs of people who are in prison,” said Hillary Blout, a former San Francisco prosecutor who helped write one of the reform measures.

Spolin acknowledged to The Times that he had given some people assessments that turned out to be overly optimistic.

“We are different than other lawyers in that we fight for the way the law should be,” Spolin said. During a three-hour interview, he predicted that courts and law enforcement would step up their use of resentencing laws in coming years, leading to the eventual release of many of the inmates he represents.

“I am so confident that history will prove me right. … All these clients who feel like they’ve been hoodwinked, and then they’re gonna win. And they’re gonna say, ‘Oh, wow. You know, Mr. Spolin was right.’ ”

Since at least 2009, when a panel of three federal judges ordered California to reduce its dangerously overcrowded prisons, the Golden State has been trying to reform its criminal justice system. Those efforts have picked up speed in recent years as mass incarceration has come to be viewed increasingly as a moral wrong that disproportionately hurts Black and Latino communities, the poor and the mentally ill.

Some reforms that the state passed concerned future prosecutions and did not apply to people already incarcerated. A pair of 2019 laws, however, did affect prisoners by allowing judges to consider inmates for resentencing and release, either on the recommendation of county district attorneys or because of changes to the murder statute that invalidated the convictions of some homicide defendants who had not carried out the actual killing. The statutes could be difficult to understand and did not apply to most people, so advocates visited prisons early on to explain the laws to groups of inmates.

A point they emphasized was that inmates didn’t need to hire attorneys.

“We were concerned because incarcerated people and their families will pay whatever is asked of them for just some hope at freedom,” said Blout, who drafted the law that allowed prosecutors to recommend resentencing.

‘We are different than other lawyers in that we fight for the way the law should be. I am so confident that history will prove me right.’

— Aaron Spolin

Not everyone attended the prison briefings on the reforms, and when an inmate was released through the laws — or there was even a rumor that someone might — word raced through the prisons. Inmates wondering whether they too had a chance shared those hopes with relatives, and before long, many ended up phoning Spolin’s firm.

The attorney provided The Times with lists of clients and relatives he suggested would tell a reporter they were happy with the job he did. Some did not return calls or messages. Two said they felt a public defender would have done a better job, and they were confused about why Spolin would have provided their names to The Times.

Others enthusiastically endorsed the firm.

“It’s been a magical experience,” said Darrell Tittle Jr., who was released in March after two decades in prison. He was convicted of manslaughter for participating in a deadly 2003 fight in which a rival San Diego gang member was shot to death. Tittle did not fire a weapon and was eligible for resentencing under the homicide reform law.

Though the law provides free legal representation for qualified inmates seeking resentencing, Tittle said he wanted a private lawyer and believed Spolin and his colleagues took his case more seriously. “I felt the public defender had already let me down through my initial trial.”

A smattering of other firms, including one started by a former Spolin attorney, have advertised similar services to inmates and families. Spolin’s firm was the first and appears to be by far the largest in California, according to interviews with government officials and advocates.

Spolin has expanded his firm to represent inmates in appeals and other proceedings in Texas, New York and Michigan, and said he plans to add clients in Pennsylvania shortly.

“I want to be known throughout the country,” he told The Times.

Ramon Valencia Pineda contacted Spolin’s firm last year “desperate to find something good” for his brother, Luis, a convicted murderer serving a sentence of life without parole.

In a phone call, Spolin recommended the family seek his release through the new law that allows prosecutors to recommend resentencing and said that for $18,500 his firm would pursue that route and a governor’s commutation, according to Valencia and a firm memo prepared for the family.

The money was daunting for Valencia, who works at a Home Depot in Stockton, and his sister, a department manager at Target. But their dealings with the law firm had filled them with hope. Spolin was bright and spoke authoritatively about their brother’s prospects. In a conference call, he said, the attorney assured the family, “You have a good case.”

Hearing about the smart lawyer ready to fight for their incarcerated relative, cousins, aunts and uncles pitched in, $500 here and $1,000 there.

It was only recently, more than a year after they had paid Spolin, that they learned Luis Valencia never had a chance of being resentenced. In a terse Feb. 1 letter to Spolin, a Merced County deputy district attorney said anyone sentenced to life without parole was disqualified under the office’s guidelines.

“I did not know that was the policy of the D.A.’s office,” Spolin acknowledged to The Times after being asked about the letter. He said Luis Valencia struck him as a good candidate and defended his ignorance of the criteria, saying of prosecutors’ offices in general, “It is very, very, very hard to get a call back.”

Reached on her office line one recent afternoon, the Merced prosecutor who oversees resentencing, Misty Compton, said she was available to provide information about the office’s resentencing policies to anyone seeking it but did not recall ever getting a call from Spolin’s firm.

The Valencia case was not the only time that Spolin urged families to hire his firm to pursue resentencing in a county where the incarcerated person did not meet the office’s criteria. His firm charged the family of Alex Ivey, also serving life without parole for murder, last year to pursue resentencing through the Alameda County D.A. A prosecutor wrote back that Ivey would not be considered because “the law currently does not permit resentencing on special circumstances cases” like his.

Spolin said a prosecutor in the office had previously told his firm inmates like Ivey were eligible.

In Santa Clara County, Spolin charged the families of at least two men convicted of murder to seek resentencing through the D.A.’s office there, according to interviews and firm memos. David Angel, the assistant district attorney overseeing resentencing, said the office is focused on inmates convicted of robbery, burglary and other less serious crimes and has never used the new law to recommend someone convicted of murder be released.

“I did not know that information,” Spolin acknowledged to The Times.

Ramon Valencia said he feels humiliated in front of relatives who gave from their meager savings and wronged by Spolin and his firm.

“Isn’t that their job to look into it?” he said recently. “It doesn’t make any sense to me that he didn’t know.”

By the time the Valencias paid, Spolin Law was a high-volume operation.

At Solano State Prison in Vacaville, one firm client, who is serving 80 years to life for murder, said that when he goes to collect his legal mail, the registry shows inmate after inmate receiving letters from Spolin Law.

Another client at the same facility offered a reporter the names and prison numbers of nine other inmates in a phone call, saying they were lined up nearby and wanted a chance to describe their own problems with the attorney.

Asked how many clients he had, Spolin said, “I don’t know the exact number. Like a lot.” He later estimated he had a couple hundred clients with active cases. He declined to provide the total number his firm has represented.

Questioned about different cases, Spolin was not familiar with the details or even the names of clients. Families interviewed by The Times said they had never met him in person, and most said they spoke to him just once at the start of his representation. Some inmates said they had never talked to Spolin. Nearly all inmates reported difficulties in reaching him or his four staff attorneys, saying that calls with lawyers took weeks or months to schedule and that they were forced to relay information through assistants, paralegals or case managers.

“If you call in, you will never get the same person,” said Emma Alford, who helped pay $30,000 to Spolin to represent her husband, Justin. “It’s a little disheartening.”

Spolin said the firm is upfront about the fact that many people will work on cases: “We tell clients it’s a team effort in terms of doing their work.”

Case managers dealt frequently with families on the cost of various services and the options for paying in installments. Some relatives strapped for cash said they felt pressured to come up with money for Spolin’s fees.

Case managers do have a financial incentive to convince families to sign up for legal services, Spolin confirmed, saying their pay “is related” to the fees they deliver.

“They get bonuses based on how hard they work,” he said. He said the arrangement did not amount to a commission system, which State Bar rules prohibit.

Spolin denied that he pushed relatives to spend beyond their means.

“There have been circumstances where people have said, ‘This is all I have.’ And I’ve said, ‘You probably don’t want to do this if this is all you have,’ ” he said.

Spolin grew up in Palo Alto, went to UC Berkeley Law, and took a job as an assistant district attorney in the Bronx. There, he worked fraud and other financial crimes cases and, according to Spolin, sat second chair on a murder prosecution.

When he moved to L.A. in 2016, he switched to the defense side.

“He didn’t have an office when we hired him. It was just him,” recalled one of his first clients, a then-17-year-old who asked to be identified by her initials, A.B. At the time, she was accused of double murder in the killing of a pregnant woman.

“His rates were very reasonable,” her mother, Mary Medina, recalled.

Spolin fought off a prosecution attempt to move the case to adult court, where the charges carried the possibility of decades in prison. Medina’s daughter ultimately served six years in a juvenile facility and was released last year.

“He did an amazing job, and there was a lot going against me,” A.B. said.

In 2018, as Sacramento legislators were passing the new criminal justice reforms, Spolin started remaking himself as an appeals specialist. He said the timing was “kind of a coincidence” and that he found post-conviction work a better fit for his personality than trials.

“I’m a very introverted person. I don’t like conflict,” he said.

To prepare, he said, he read a textbook about California appellate law and attended a training conducted by judges. He registered Spolin Law as a business in March 2019 using the address of a co-working space on Olympic Boulevard. Employees work remotely from locations all over the country and world.

That decision and others about how to run the firm were influenced by a year and a half Spolin worked at McKinsey after getting an undergraduate degree from Princeton, he said. His time “analyzing how different companies could expand to be successful” led him to embrace new techniques at his firm.

“I want to take what works and discard what doesn’t,” he said.

Aggressive internet advertising was one of the things that seemed to have worked. Spolin hired a digital marketing specialist from Ohio with expertise in Google ads and a goal, stated on his website, “to make my clients phone ring and help them scale their service business.” His other clients included carpet cleaning franchises in suburban Columbus.

Inmates searching for options under the reform laws were presented with paid posts about Spolin. His website featured long articles about the new reform laws, photos of Spolin smiling confidently, and big claims about his reputation and skills.

Though few in L.A.’s legal establishment had ever heard of him, Spolin marketed himself as a widely regarded expert with a firm “in the top 0.4%” of criminal firms nationally. “Multiple independent rating agencies” ranked his firm at the top of its field, he told inmates in letters.

The designation actually came from for-profit outfits that offered Spolin and other lawyers the chance to buy a package, currently priced at $395, that included a wall plaque and permission to advertise their rankings. Spolin said the companies approached him and that he no longer pursues such rankings, which he called “the poor man’s Super Lawyers,” a reference to the glossy legal magazines in which many high-end lawyers advertise.

Whatever its basis, Spolin’s promotional material impressed people like Amanda Allen, whose then-husband, Johnte, was serving life without parole for a 2006 murder in Bakersfield.

“It was just the whole headline,” she recalled. “He said he was the top attorney.”

When she called the firm, she learned of what Spolin described as another McKinsey-inspired innovation: the $3,000 case review.

Before inmates or families talked to Spolin, they had to pony up a retainer that they were told would be used to research their case and evaluate their options. If they wanted to pursue one of those options, the $3,000 would be applied to the bill. If they didn’t, the firm kept it.

Veteran appellate attorneys in California said free or low-cost initial consultations were the norm in the field.

“$3,000? To just look at the case, which probably takes five minutes,” said Paul J. Cohen, a Van Nuys appellate attorney who represents both paying and indigent clients. “I don’t charge more than $500 for a consultation where I actually go to the jail, and usually I don’t charge anything.”

Spolin defended the practice, saying his firm’s approach was more rigorous and valuable. Other lawyers, he said, might “give an off-the-cuff remark, but they’re not getting records, and looking at records and then giving a detailed analysis and a detailed report.”

Coming up with $3,000 was a challenge for Amanda Allen, an administrator at a group home who said she lives “paycheck to paycheck,” but the hope of getting her husband’s sentence reduced was a strong motivation to scrimp and save.

After she paid, she received a memo outlining the options. Spolin reiterated them in a telephone conference. Johnte Allen, listening from prison, was not impressed.

“He was supposed to look over my transcripts, but he didn’t know anything at all,” he said in an interview from Kern Valley State Prison.

Spolin recommended a $20,000 package that included seeking resentencing through the local D.A.’s office. The suggestion struck Allen as absurd. His crime was notorious in extremely conservative Kern County. Just two years earlier, a D.A. candidate had bragged about convicting Allen. Now, Spolin wanted to charge his family to ask the same office for a break?

“There was no way possible. I wasn’t even incarcerated long enough or rehabilitated enough at that time to even be thought of for that specific deal,” he said.

The memos Spolin’s firm prepares for families who pay $3,000 normally run about 14 to 20 pages and are based on a template. A Times review of more than a dozen prepared for families across the state showed that though they do include specific details from inmates’ cases, most of the memo is boilerplate explanations of the various legal avenues available to inmates. Even some of the information that appears to be specific to an inmate is canned.

“We were pleased to learn that Mr. [inmate] has strong family support to help him integrate into society upon his release from prison,” read portions of memos prepared for a half-dozen different families. “This will ensure that Mr. [inmate] will not be destitute on the street and will have a place to stay and facilitate the resumption of a normal life.”

Spolin said the memos had value to families who need a primer on the law and an understanding of what opportunities there were for their loved one: “We are not saying we are giving them anything else.”

Drafting these memos was sometimes delegated to contract lawyers hired through sites like Indeed. One attorney from a developing country said he was paid about $10 an hour to fill out the templates using records and questionnaires answered by inmates. The recommendations he made in the memo were passed up to a licensed California lawyer working at the firm, and he had no direct dealings with families.

‘There was nothing to lose. That was the justification. These were already incarcerated people.’

— Attorney from a developing world country who stopped working at the firm last year

The developing world attorney, who stopped working at the firm last year and spoke on the condition of anonymity to preserve his job prospects, said he met Spolin over a videoconference once during the job interview. Spolin, he said, remarked that the pay was “at least twice as much as the average Philippine legal salary.”

Spolin said in an interview that the firm had used foreign lawyers to carry out paralegal duties in the past, but stopped because the international attorneys’ “English level was not good enough in terms of research and looking at cases and that kind of thing.”

The developing world attorney told The Times that he had no prior training in appellate law or California’s criminal justice reforms. He said he recommended two services to almost every family — commutation applications and pursuit of resentencing through the D.A. — because they theoretically applied to every inmate.

“There was nothing to lose. That was the justification. These were already incarcerated people,” he said.

Gascón’s election as L.A. district attorney presented Spolin with a huge business expansion opportunity.

About one in every three inmates in the state prison system — more than 30,000 people — was convicted in L.A., and Gascón had campaigned on reducing mass incarceration. Shortly after taking office in December 2020, he issued a “special directive” pledging “a comprehensive review of cases where the defendant received a sentence that was inconsistent with the charging and sentencing policies” his office had embraced. By Gascón’s own estimation, more than 20,000 inmates fell into this category.

“It is like a defense lawyer is running the D.A.’s office,” Spolin recalled thinking.

He featured Gascón on his website describing him as one of the district attorneys “eager to reduce sentences.” In calls with families considering hiring the firm, Spolin invoked Gascón’s name frequently. He acknowledged to The Times that he expected large numbers of inmates, including people convicted of murder and other violent offenses, to get hearings within six to eight months.

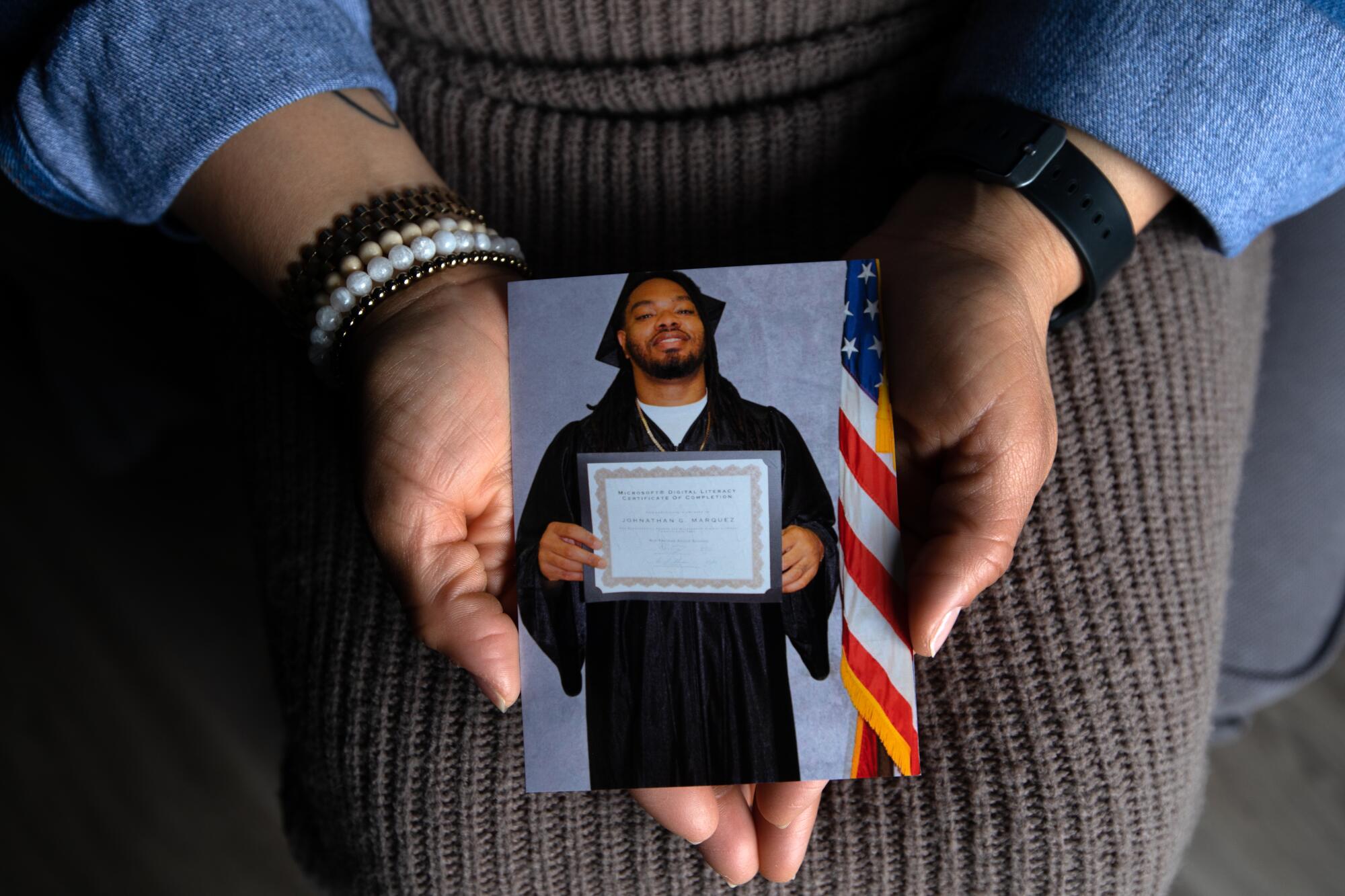

Johnathan G. Marquez, serving 75 years to life for murder and attempted murder, said the lawyer spoke of the D.A. “like him and Gascón are college buddies.”

“We’ve got a guy in there right now who is a big reformer and a proponent of policy change,” Marquez recalled Spolin saying. “The time is now, Mr. Marquez, for you to get your documents in there and to get out of prison.”

In reality, Spolin had never met or talked with Gascón, and advocates who helped write the D.A.’s “special directive” said the lawyer’s analysis was way off.

“I think it was clear to anyone involved it was going to be a slow and cautious process,” said Christopher Hawthorne, a Loyola Law clinical professor who helped author the document. Asked whether he expected the D.A. to move quickly to seek the release of many people convicted of serious offenses, he said, “Under no circumstances.”

Any doubts might have been cleared up just two months later, in February 2021. Gascón announced that a special resentencing unit would work with the prison system to identify inmates who fit specific criteria. They included inmates 50 years and older serving sentences for nonviolent and nonserious offenses, and inmates serving sentences for crimes other than homicide committed at age 14 or 15.

“When there is a determination that your case is being considered, you will be notified in writing,” the D.A.’s website stated, adding that the resentencing unit could not “accept calls, emails, letters, or other submissions regarding individual cases.”

In response to a question in an FAQ about whether inmates needed to hire attorneys, Gascón’s office was emphatic: “The District Attorney’s Office is not considering recommendations for resentencing by outside counsel. Therefore, a lawyer cannot initiate or accelerate the review process for an individual case.”

Asked multiple times when he learned of the D.A. policies, Spolin did not provide an answer.

In the period after Gascón announced his criteria and for months after, Spolin kept selling inmates on their prospects for release. He said for about $12,700 he would prepare an “application” for the D.A. of several hundred pages including a persuasive memo for the D.A. about their rehabilitation, character letters, post-release work plans and other information.

“They just said they had been very successful,” said Marquez’s wife, Karen, a bookkeeper who participated in a conference call with Spolin and several colleagues about resentencing. She said she and her mother-in-law paid the firm in installments through April 2021 unaware of the D.A. policy unveiled months earlier. “They painted a picture like they had experience with this and they have had people resentenced successfully and who are now out and free.”

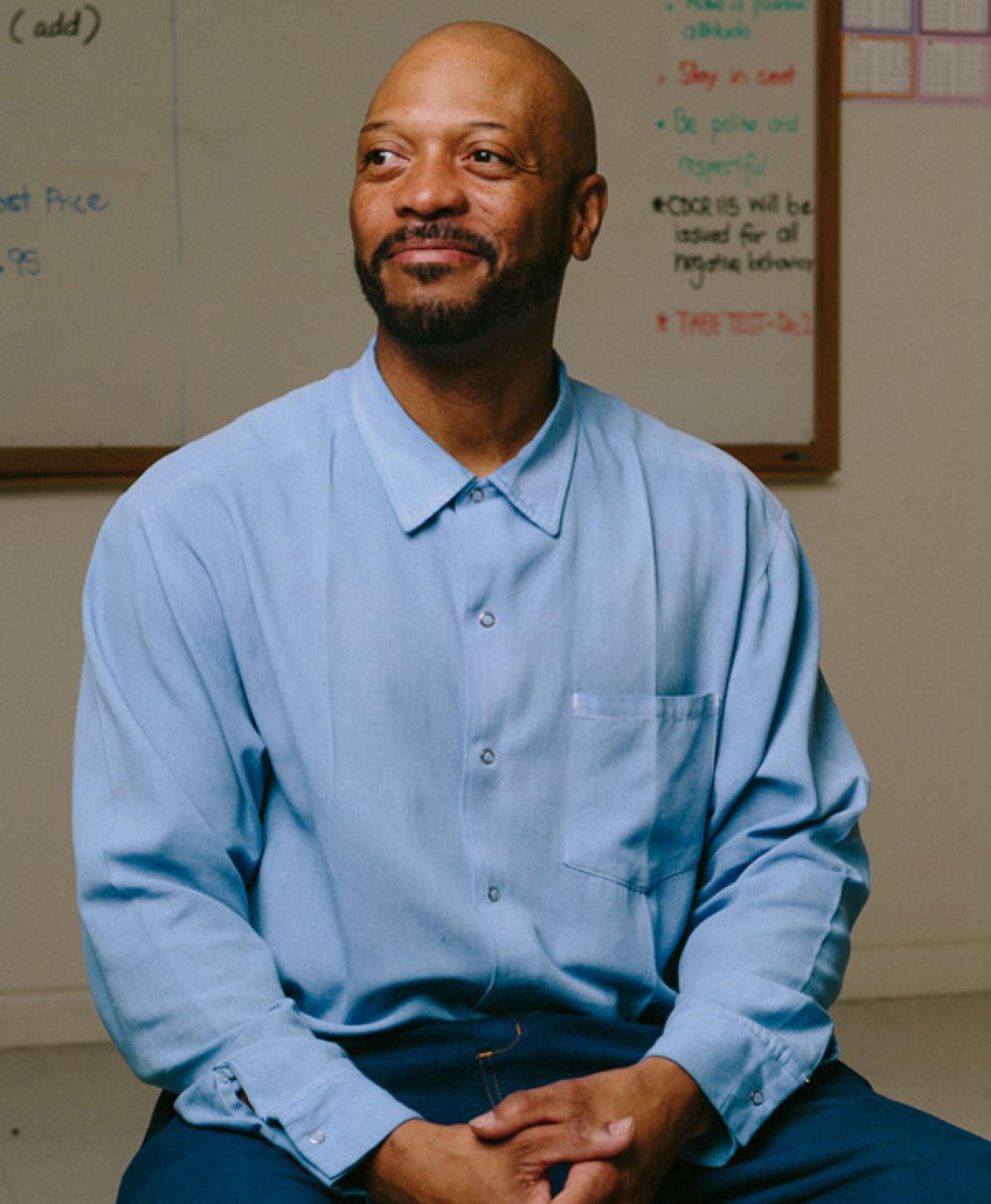

Shaylor Watson, serving life without parole for two murders committed in the 1980s, said Spolin told him that asking for resentencing through the D.A. “was my quickest course of relief.”

“I thought I was going to be the first one to be resentenced because I had been in for more than 30 years,” said Watson, whose resentencing request was submitted in May 2021. A friend and her sister put up $12,000 for legal fees, he said.

Eddie Hunter Jr., sentenced to 24 years for manslaughter he committed as a teenager, said Spolin spoke of his chances with a lot of confidence.

“He told me I was a prime candidate. He told me my case belongs on the firm website,” said Hunter, whose girlfriend, then a home health aide, used money she had set aside to buy a car to pay Spolin.

The Marquezes, Watson, Hunter and other inmates and families said Spolin did not tell them of the D.A. criteria or the explicit instruction not to send materials to the office when he pitched them on the service.

Correspondence provided to The Times shows the lawyer informed some clients of the D.A. criteria in writing months after they paid. The letters were largely identical but sent at different times — Watson’s in September 2021; Marquez’s in December 2021, another man’s in January 2022.

“To be clear, while you do not meet the current priority criteria it does not mean that you are ineligible,” the letter read.

Clients expecting to get out of prison within a year were devastated. In Folsom, Wesner Charles Jr., whose actor sister and other relatives had paid $19,000, learned of the D.A.’s policy from another inmate. In an angry January letter, Charles accused Spolin of deception.

“You knew my case was [a] serious and violent felony, and you still elected to charge my family and for a service that didn’t fit me,” he wrote.

Spolin denied deceiving the Charles family and said he still considered him a good candidate for resentencing. He said he initially expected the D.A.’s criteria would only be in effect “for the first few weeks” before the office began evaluating other classes of inmates, including those serving time for serious and violent felonies. He acknowledged, though, that he did not contact Gascón or any of his prosecutors to get firsthand information.

“It’s very hard to get a phone call with a high-level person,” he said.

Asked recently by The Times about its approach to resentencing for violent offenders, Gascón’s office said in a statement, “As a general rule, a person convicted of murder or another violent or serious crime is not regarded by our office as a good candidate for resentencing absent unusual or extraordinary circumstances … .”

More than two years into office, Gascón’s resentencing unit has recommended about 60 people or about 0.2% of the L.A. prison population for resentencing, according to a list of cases provided by his office. Most were for nonviolent crimes.

‘He told me I was a prime candidate. He told me my case belongs on the firm website.’

— Eddie Hunter Jr., sentenced to 24 years for manslaughter he committed as a teenager

Many families continued to believe the D.A. was evaluating their cases, and Spolin encouraged this belief in form letters telling them, “No news is good news, as the delay may indicate they are conducting a thorough review of your case and the documentation we sent.”

In May 2022 — a year and a half after Spolin started billing families to pitch Gascón cases for resentencing — one relative grew frustrated and decided to go straight to the D.A.’s office himself. The man, who had paid Spolin about $11,000 on behalf of his incarcerated son, was connected with Diana Teran, the director in charge of Gascón’s resentencing unit. She explained that the office was identifying cases on its own and didn’t need outside suggestions, according to their email correspondence.

The man pressed her to look for the packet from Spolin, but she couldn’t locate it, and as they communicated further, it emerged that the mailing address the law firm had used was incorrect. Packets were not going to Teran’s department, but to another office in the large downtown headquarters, according to their emails and subsequent correspondence with Spolin.

Unsettled, the inmate’s father emailed the Spolin firm about the mistake, even providing him Teran’s direct email address, the correspondence shows.

The information raised the possibility that hundreds of packets for which families had paid dearly were languishing unread somewhere on Temple Street.

Spolin himself didn’t reach out to Teran. Instead, the job fell to a paralegal assistant working remotely from a small city northwest of Atlanta. She had no legal education and was balancing her duties at the firm with gigs as a ukulele and voice instructor, according to an online resume.

“We recently received information indicating that all requests for resentencing should be submitted to your specific department,” Jessica McRee wrote to Teran. “Do all of our resentencing requests need to be resubmitted to your department? We were also wondering if there is a way to check on the status of previously submitted [resentencing] requests.”

Teran responded the same day: “I do not know where your requests may have gone as the District Attorneys Office has received thousands of them and does not have the staff to respond to all of them which is why we posted information regarding the process on our website.”

The D.A.’s office announced a change to its policy in November, saying people who did not fit the resentencing unit’s criteria could ask head deputy district attorneys for review. Of the very few that have been granted, none have been submitted by Spolin.

“He’s inundated the entire office,” said Bobby Grace, an assistant head deputy in South L.A. who estimated he had received about a hundred packets from Spolin. “His name is on everyone’s lips and not in a good way.”

Packets sent in by Spolin recently are often “boilerplate,” he said, and lack information about whether an inmate has gotten into trouble in prison, a key factor for him in evaluating whether they deserve consideration.

“A lot of these people could be weeded out by them quickly,” he said. “They had real disciplinary problems that he didn’t address…”

Told he was charging up to $12,700 for the submissions, Grace appeared stunned: “Seriously? Wow.”

Spolin, informed of the prosecutor’s criticism of the quality of his submissions, pledged to improve and said, “I appreciate the feedback.”

He has submitted hundreds of resentencing packets to district attorneys around the state. The Times asked him whether any had been successful. He pointed to one: a man in L.A. County whom he identified only by the initials J.G. The Times determined the man’s identity and contacted him.

“That’s not true,” said Johnny Guevara, released last year after serving 24 years for a carjacking and kidnapping he committed at age 14. “I give Aaron Spolin zero credit.”

He said his single mother saved money from babysitting and other odd jobs to pay Spolin about $13,000, but the submission to the D.A.’s office in 2021 got no response. (Spolin subsequently confirmed Guevara was J.G.)

Months later, corrections officials identified Guevara as a youth offender who met the D.A. criteria and Gascon’s office asked a legal clinic at Loyola Law school to represent him and about 60 other similar inmates for free. The packet prepared by professor Christopher Hawthorne and his students formed the basis of the decision to recommend him for resentencing last year, the D.A.’s office and the professor confirmed.

“This is the first I’m hearing of almost all of this,” Spolin said when pressed for an explanation. He said he still considered the case “a win” for his firm because they had sent the district attorney a lengthy packet about Guevara and “it’s reasonable to assume it went into his file.”

Once released, Guevara demanded Spolin return his fees.

“I told him, ‘Aaron, you pretty much took my money, my family’s money and I deserve to get some back,’ ” he said. Eventually, he said, the firm reimbursed the family $4,000.

After the governor commuted the sentences of 21 inmates in June 2020, Spolin heralded his connection to one of the fortunate inmates, James Heard.

“California Governor Gavin Newsom has announced the commutation [reduction] of sentence for a Spolin Law client who was previously serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole,” his law firm crowed in a post on its website, adding, “The client’s family was extremely happy to hear this good news.”

Reached in the state prison in Lancaster, Heard said the law firm’s claimed connection to his commutation was “intentionally misleading.”

“The firm did not do that for me,” said Heard, who is awaiting a parole hearing. “I’m the one who did my commutation, my entire commutation packet. I filed it and everything.”

His family hired Spolin without his knowledge to do a case review shortly before the commutation came through, Heard said. He had submitted the application to the governor’s office years earlier.

He said he learned Spolin was using him as a marketing tool from other inmates, “strangers I didn’t know, saying, ‘Is your name James Heard? Do you know about Spolin? You are on his website.’ ”

It bothered him, he said, adding of Spolin, “You are intentionally misleading people. You are not telling them we didn’t represent him in this matter.”

Asked about Heard, Spolin said he had never claimed to have prepared the commutation application and that the purpose of the blog post was to “celebrate the client’s big win and show how Gavin Newsom is granting commutations even on murder cases.”

The $3,000 case reviews Spolin’s firm produces give families an encouraging view of commutations, based in part on 283 commutations under Gov. Jerry Brown, including people convicted of murder.

“Therefore, pardons and commutations are a very real possibility for all types of inmates,” the case reviews inform families.

Newsom has granted 123 commutations as governor, including for murder and other violent crimes. While some experts say they aren’t against private attorneys charging for commutation applications, they were adamant that clients need to be told that the chances of success for any individual inmate remain minuscule.

Spolin routinely recommends proceeding with these applications at a cost of as much as $14,700, according to applications reviewed by The Times and interviews with people familiar with the firm’s filings. Spolin did not identify any clients for whom he had filed successful commutation applications and The Times was not able to find any.

‘Strangers I didn’t know, saying, “Is your name James Heard? Do you know about Spolin? You are on his website.” ’

— James Heard, incarcerated and awaiting a parole hearing

He said he does not urge all of his clients to pursue commutations. “When we recommend it, based on the information we have at the time, they do have a chance,” he said.

Spolin offered package deals to some families. They could pay about $18,000, and he would prepare two very similar packets of information about an inmate — one would be sent to D.A.’s offices for resentencing and another to the governor for commutations. The packets ran hundreds of pages, but much of the material was made up of articles about the problem of mass incarceration that had little to do with the particular applicant.

Families paid for applications for inmates that commutation experts said would never be given serious consideration. One Spolin submitted this year was for a man who had been sentenced only two years earlier for attempted murder and assault. Several others had records of recent serious disciplinary problems in prison, including fighting, that people familiar with commutations said would make them unsuitable in the governor’s eyes.

The wife of one prisoner who said she dug into her 401(k) to pay Spolin’s fees repeatedly pressed the firm about whether the disciplinary write-ups in her husband’s “C-file” or prison record could be a problem for getting a commutation.

“In regard to the Governor’s review of [the prisoner’s] C-File, it is up to their discretion what they will be reviewing,” a Spolin Law assistant told her in January.

Katharine Tinto, a UC Irvine clinical law professor who runs the school’s criminal justice clinic and has prepared successful commutation applications for free, said that the governor’s office looks closely at the prisoner’s record and “if the person has a disciplinary history in prison that is recent and serious, he is very unlikely to get a commutation.”

Jesus Del Villar, a Corcoran inmate about a decade into a 37-year sentence for manslaughter and other offenses, had much more than a poor disciplinary record when Spolin submitted his name for commutation this year. He had admitted in federal court last spring to running a drug ring from his cell.

“The defendant used contraband cellphones to direct other members of the conspiracy to weigh, package, conceal and transport ounces of cocaine and pounds of methamphetamine and heroin from sources of supply to drug distributors,” read the plea agreement Del Villar signed in April 2022.

It was unclear who paid Spolin’s bill of approximately $9,500. Del Villar did not return messages, including one relayed through a relative.

“He absolutely deserves it,” Spolin said in response to questions about Del Villar’s suitability. “The fact that he has not had a perfect environment in the prison is not one that should disqualify him.”

Nguyen Le Nguyen was 17 years into a sentence for murder when his family hired Spolin. His relatives did not speak English fluently, he said, and had been talked into paying about $23,000 for legal services, including some he did not need — such as a petition arguing that he was innocent.

“I would never file for actual innocence,” he said recently, noting that he had pleaded guilty in the San Jose killing and that he was preparing to go before the parole board and outline his remorse. “I said ‘Don’t go forward,’ but [Spolin Law] said it’s done. They charged me anyhow.”

There was one service that did fit Nguyen’s situation — resentencing under the reform law that applied to certain homicide convictions. On the day of Nguyen’s hearing, Spolin sent a contract attorney who had not read recent case law on the reform and argued a theory that didn’t fit the circumstances of the shooting, a transcript of the proceeding showed. The resentencing request was denied.

A court-appointed attorney later argued for a new hearing partly on the basis of ineffective counsel, noting, “There is no conceivable reason for counsel not to have sufficiently familiarized himself with the facts of the present case.” The appellate court sided with Nguyen though it did not weigh in on Spolin Law’s performance.

Nguyen was released on parole in January. Before he walked out of Folsom, he typed up a complaint against Spolin on his prison-issued tablet and asked that it be forwarded to the State Bar of California.

Spolin declined to discuss Nguyen’s case in detail, but said, “We did not take advantage of Mr. Nguyen’s family…There was definitely no intention to send someone who didn’t know the facts of the case.”

Nguyen’s complaint was one of several attempts over the years to get authorities to look into Spolin. In October, a frustrated appellate attorney in Oakland contacted the L.A. D.A. office to request a criminal fraud investigation of the law firm.

“I have attached materials regarding his business practices generally… so you can see proof of what I believe is a sophisticated scheme to convince desperate families to pay thousands of dollars for sentencing relief [for] loved ones that simply does not exist,” wrote Jenny Brandt, who now works for the Alameda County public defender.

Gascón’s office does not appear to have opened a criminal probe, but they subsequently reported Spolin to the State Bar. By December, that agency had launched an investigation into Spolin’s firm, according to correspondence shared with The Times.

Several attorneys alarmed about Spolin’s practice said they had met with the State Bar’s top prosecutor, Chief Trial Counsel George Cardona, to lay out their concerns.

“The State Bar is expending significant resources into its investigation” of Spolin, an agency prosecutor, Akili Nickson, wrote in an April 10 update to one lawyer shared with The Times. “Mr. Cardona has assigned an entire team of prosecutors and investigators to the matter. The investigation is robust and involves close cooperation of our law enforcement partners.”

Spolin said some appellate attorneys complaining about him are upset about losing clients to his firm.

“We have been more and more successful. We’ve taken work away from them. We’ve negatively impacted many of their incomes,” he said.

The complaints haven’t stopped Spolin from courting inmates and their families. Allen, the convicted murderer from Bakersfield who rejected Spolin’s suggestions three years ago, said he received an unsolicited letter from him in March offering different services.

“Now he’s a habeas expert,” Allen said sarcastically.

In recent months, Spolin has started recommending families pursue a new reform passed last year that allows inmates to challenge their convictions on racial discrimination grounds. The cost quoted is $24,700.

Slowly building a life outside of prison, Nguyen said he remained angry at Spolin. What bothered him most, he said, was how the lawyer “violated” the bonds between inmates and the loved ones who never give up on them, no matter how long the sentence.

“Our families love us,” he said, his voice cracking. “They help us the best they can.”

Times staff writers Matthew Ormseth and Brittny Mejia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.