Discovery of antibiotic-resistant superbugs in L.A. wastewater sparks worry

- Share via

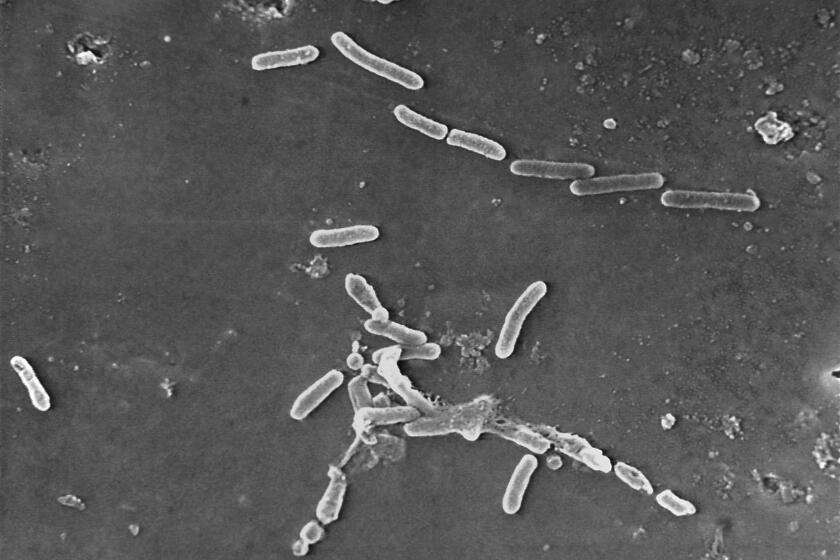

Bacteria that are resistant to colistin, a last-resort antibiotic, have for the first time been detected in Los Angeles County wastewater, suggesting that the germs are circulating more widely in the community than previously thought, according to researchers at USC.

The superbugs were discovered during surveillance of wastewater — a practice that took off during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way to track the presence and transmission of infectious agents within a community.

The pathogens appeared in samples of untreated water taken from two of Los Angeles County’s largest treatment plants: the Joint Water Pollution Control Plant in Carson and the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Playa del Rey. The facilities serve a total of about 7.5 million people.

Testing found antibiotic resistance genes on two novel small plasmids, circular pieces of DNA that can be shared among different types of unrelated bacteria, said researcher Adam Smith, associate professor of environmental engineering at USC, whose findings were published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

“This is probably the scariest aspect: the potential for this resistance to spread widely across different bacterial populations,” Smith said.

Hospitals and government need to take more action to control antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are becoming an ever greater threat to patients.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing world health threat. More than 2.8 million infections resistant to antimicrobials — which include antibiotics as well as antifungals and antiseptics — take place in the U.S. each year, and more than 35,000 people die as a result, according to estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scientists worry that widespread resistance to antimicrobials would usher in an age when common infections and minor injuries can once again kill.

“We could get to the point where we can’t combat infections with antibiotics,” Smith said, “so we’re entering sort of a post-antibiotic world.”

Colistin is an old antibiotic that’s considered the last line of defense against certain infections, including those that are resistant to carbapenems, another last-resort class of antibiotics. In their analysis of L.A. County wastewater samples, researchers detected two pathogens that not only are resistant to colistin but also have genes that should make them resistant to carbapenems, Smith said.

“That means if someone is infected, we have very little at our disposal with which to treat them,” he said.

The pathogens are opportunistic, meaning they could sicken immunocompromised people rather than healthy hosts, Smith said. But the location of the genes means the resistance could spread to pathogens that are capable of infecting the general population, he said. In fact, Smith said, such a progression is inevitable if steps aren’t taken to limit antibiotic resistance.

Colistin resistance was originally discovered in 2015 in China and has been documented on every continent except Antarctica, Smith said. That includes in Los Angeles, where a resident who died in 2016 was found to have been infected with E. coli bacteria that carried a colistin resistance gene.

Researchers theorize that a widely used degreasing chemical -- found in the soil near some residential areas -- may be linked to Parkinson’s disease.

A county resident was also infected with colistin-resistant E. coli in 2018, said Dawn Terashita, associate director of acute communicable disease control at the county Department of Public Health, which monitors antibiotic-resistant infections. The gene conferring the resistance so far doesn’t appear to have spread rapidly among pathogens even though it’s been present in the community for some time, and colistin-resistant infections remain rare, she said.

“Finding it in the wastewater is not surprising, and it’s nothing for the general public to worry about,” she said.

But the USC researchers’ findings suggest that bacteria resistant to colistin are increasing in the L.A. County population, Smith said.

“One reason why antimicrobial resistance is considered the ‘silent pandemic’ is that the spread of resistance can go undetected until it spreads into pathogenic bacteria and infections are reported to the county public health department,” he said.

The CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System is expanding this year to monitor microbial resistance genes, including those that confer resistance to colistin, spokeswoman Kristen Nordlund said.

That comes as the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have accelerated antibiotic resistance cases, with the CDC last year reporting an increase during the first year of the global health crisis.

In L.A. County, the demands of the pandemic meant that many long-term-care facilities were faced with a high volume of patients and shortages of staff and personal protective equipment such as gowns, gloves and masks, Terashita said.

“Any time you have a problem with the supply of protective equipment, you can have issues where you have more transmission,” she said.

Scientists believe the uptick came about also because antibiotic stewardship programs, which seek to limit unnecessary use, took a back seat, exacerbating over-prescription, Smith said. And because antibiotics kill all bacteria except those that are resistant to the drugs, they serve as a selective pressure that allows only the resistant bacteria to survive, he said. These bacteria are then excreted in wastewater and can further spread into the local environment, he said.

Numerous homes that underwent remediation have been left with lead concentrations in excess of state health standards, according to USC researchers.

The spread of antibiotic resistance through effluent is a big concern worldwide, said Diana Aga, a chemistry professor at the University of Buffalo and director of its Research and Education in Energy, Environment and Water Institute.

“One of the many reasons why there are antibiotic resistant bacteria that emerge is because we find many chemical pollutants, including antibiotic residues, in the environment at low concentrations,” including in bodies of water where wastewater is discharged after treatment, she said. “Constant exposure of bacteria to antibiotics is the ideal environment for creating superbugs.”

Newer wastewater treatment plants are more likely to use technologies that remove antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but some aging ones do not, she said. These plants can magnify antibiotic resistance by giving genes that confer the resistance the opportunity to spread among different types of bacteria in activated sludge, she said.

“So the older plants that may not have effective ways of removing antibiotic resistance genes become hot spots for antibiotic resistance,” she said.

A study conducted at the Carson facility showed its tertiary treatment plants remove 99.9999% of bacteria using chlorine, a disinfectant with a long, proven track record of success, said Bryan Langpap, spokesman for Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts.

Anecdotally, there has been no evidence of unusual levels of antibiotic-resistant illnesses in staff who work around wastewater, Langpap said.

“However, we recognize that more information is needed to better understand the risks. We support continued research to fill the knowledge gaps and inform decisions and actions,” he said.

As investigators probe a hazardous materials release at a Martinez refinery, residents question why it took so long for officials to issue a warning.

At the Hyperion plant, the normal treatment process, which includes primary and secondary stages, removes 90% to 99.99% of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes even without any additional treatment, said Mas Dojiri, chief scientist at Los Angeles Sanitation and Environment. The plant discharges its effluent five miles out into the ocean, and more than 40 years of water-quality monitoring has indicated that it does not encroach into shoreline recreational waters, he said.

Still, these safeguards don’t always work as intended. Hyperion came under heavy criticism when it released millions of gallons of untreated sewage into the Santa Monica Bay in July 2021, with a report citing equipment failures, unheeded alarms and insufficient staffing.

And even when all systems function as intended, disinfection does not destroy DNA in a way that renders antibiotic resistance genes benign because they can exist outside cells, as in plasmids, Smith said. Those genes and antibiotic-resistant bacteria can also enter the environment through biosolids — solid matter recycled from sewage — which are typically applied to non-food crops such as cotton as a fertilizer, he said.

In addition to ensuring wastewater treatment plants are equipped to combat antibiotic resistance, it’s crucial to curtail the overuse of antibiotics in both people and livestock, Smith said. Wastewater surveillance could also be used to more precisely pinpoint where antibiotic resistance is most prevalent and target interventions such as limitations on the prescription of certain drugs, he said.

“There’s growing evidence that if we don’t get a handle on the antibiotic resistance,” he said, “the number of deaths that occur worldwide because of antibiotic resistance will eventually make it the next pandemic.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.