Los Angeles police accidentally release photos of undercover officers to watchdog website

- Share via

In a still-unfolding drama that has reached its top ranks, the Los Angeles Police Department accidentally released the names and photos of numerous undercover officers to a watchdog group that posted them on its website.

The controversy began late last week when the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition launched a searchable online database — called Watch the Watchers — of more than 9,300 city police officers’ photos, complete with their names, ethnicity, rank, date of hire, division/bureau and badge numbers. The group called the site the first of its kind in the country.

Stop LAPD Spying officials said they believe police officers are not entitled to the same expectation of privacy as other residents because of their status as civil servants. They said in an interview about the site that what they published was obtained through a public records request by a civilian journalist and turned over by the LAPD.

Department leaders said over the weekend that the release of pictures of officers working in an undercover capacity was inadvertent, and they have launched an internal investigation to determine how the mistake occurred.

After the site went live Friday, the Los Angeles Police Protective League, which represents rank-and-file officers, put out a relatively tame statement expressing frustration that the department did not tell it about the disclosure before it went public. But those concerns about officer privacy were surpassed by a firestorm that spread through the department’s upper ranks over the weekend.

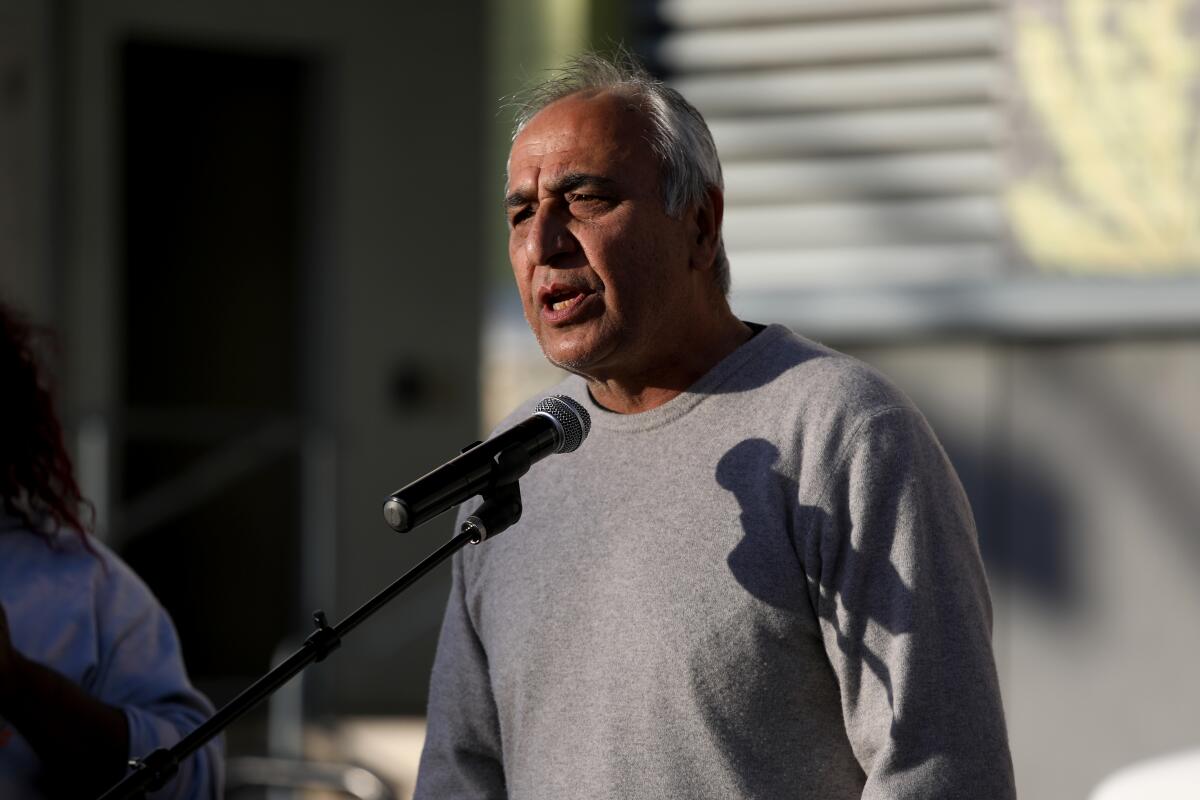

“If this is the case, first of all, we are just going off of what was given to us by the department and the city attorney’s office,” said Hamid Khan, a coordinator with Stop LAPD Spying, an activist organization that opposes police intelligence gathering and is pushing for widespread reform.

Khan called it deeply ironic that the department would be opposed to such a disclosure, considering its history of surveilling and gathering information about residents.

“We’re not publishing their home addresses, we’re not publishing things that are outside their role as police officers,” he said.

The group has long pushed for radical transparency around the LAPD, arguing that outside oversight bodies have routinely failed over the years to expose and keep in check police misconduct. Khan said that if the police union disagrees with the disclosure, it should take up its grievances with the LAPD — which ultimately released the photos, based on a court ruling in another jurisdiction.

Police officials said that even if the information was obtained legally, it could still compromise the safety of officers who normally operate in the shadows.

In a department-wide email Saturday, Police Chief Michel Moore said he learned of the disclosure “after it had occurred and had in fact expressed my opposition to such a release in a media interview earlier that day.”

“I apologize to each member of this department impacted, and your families, for not having provided you with advance notice of this release. While I recognize that apology may be of little significance to you, each of you should be able to depend on me and this department to demonstrate the appropriate sensitivity in these types of situations,” Moore said in the email.

Th email also said he called for an internal investigation into the release of the photos, which were given to an unnamed party in September under a public records request. At some point, Moore’s email said, the photos were obtained by a third party, a possible reference to Stop LAPD Spying.

“The investigation will include the timeline of events, those involved, the underlying analysis and rationale in reaching the decision to release the information, and protocols employed,” Moore said in the email. “Additionally, it appears that once the decision was made to release the information, that appropriate safeguards were not put in place to ensure those assigned to sensitive investigations were not included, and that steps were taken to alert our membership of the required release.”

He said that those involved “in the decisions and actions” would be held accountable, while adding that this wasn’t intended to be a “scape goat” investigation.

The police union filed a formal complaint related to the disclosure Monday against Moore and Lizabeth Rhodes, director of the LAPD’s Office of Constitutional Policing.

“We demand to know who knew what and when did they know it?” the union said in a statement. “If the chief did not know, as he has claimed, then who did and when will they get shown the door? We will also be pressing to ensure those officers that are working in sensitive assignments are accorded the appropriate security to keep them and their families safe.”

Multiple LAPD sources not authorized to discuss the photo scandal said Rhodes, the administrator overseeing the handing over of the images, should have actively reached out to divisions to ensure any officer working in an undercover capacity was excluded from the photo disclosure.

Some of those in the photos are also working with other agencies as part of federal task forces, the sources said, and the disclosure may have also hurt that work and working relationship. The sources said the existence of the photo files could also make it hard to consider bringing into undercover operations anyone whose photo may now be on the publicly available database.

Another LAPD source who works with undercover units described “shock and panic that shuddered through their ranks and families” after the department chose to release images of officers and detectives who work particularly sensitive undercover details, involving cartels, gangs, narcotics and even counter-terrorism.

LAPD sources said the photos’ release came after Santa Ana was ordered to reveal its officers’ photos following a legal battle.

Rhodes was in charge of the photos’ release in concert with the city attorney’s office. But the actual names and images were generated by administrative staff and only a handful of personnel who work in an undercover capacity were excluded, according to the sources.

“This was a huge mistake,” one LAPD source said. “There is no doubt some operations were compromised if someone were to see an officer’s photo working it.”

Seth Stoughton, a former Florida police officer and law professor at the University of South Carolina who studies policing, said releasing photos of officers in undercover positions “can absolutely compromise their identity.”

Stoughton said he obviously favors transparency, but this is a fundamental issue of officer safety when a department is asking some men and women on the force to take much more serious risks than a normal police officer.

“All it takes is someone to train a facial recognition program on these photos. While the average criminal doesn’t have those assets, the kind of people investigators target in deep-cover operations may well have such products or technology experts,” Stoughton said. He said the department will have to assess which if any of its undercover assets are compromised.

At the same time, he said, “it may not be as God awful as it seems because officers working undercover tend to take on another appearance from their official police photos.” He added that it is also likely that many officers’ photos are already on social media.

For the record:

10:36 a.m. March 21, 2023An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported that the watchdog group Stop LAPD Spying Coalition may release photos of the department’s more than 3,000 civilian employees. The group says it has no intention of doing so.

The photos are featured on a website Khan, of Stop LAPD Spying, said will prove a useful “accountability” tool for activists, academics and amateur “cop watchers” who monitor police-civilian encounters for potential excessive force and abuses. The database will be updated periodically and will probably grow over time, populated with data on officers’ disciplinary histories and salaries as the group obtains them through public records requests.

“What we are doing is, we are just flipping the camera on them and saying, ‘This is who you are, this is what you do, this is what you have done,’” said Khan, a regular at City Hall and Police Commission meetings.

The site was born in part out of necessity, Khan said, noting that some officers at protests are known to shield their identity, making it hard to file complaints when misconduct occurs.

He said activists had already used the photo database to identify an officer who appeared to be mocking residents and advocates at the controversial cleanup of a homeless encampment in skid row this year.

Stop LAPD Spying remains locked in a protracted legal battle with the department over the LAPD’s refusal to release data on each officer’s height and weight. Attorneys for the department contend that such details constitute an “unwarranted invasion of personal privacy” and could put the officers at risk.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.