- Share via

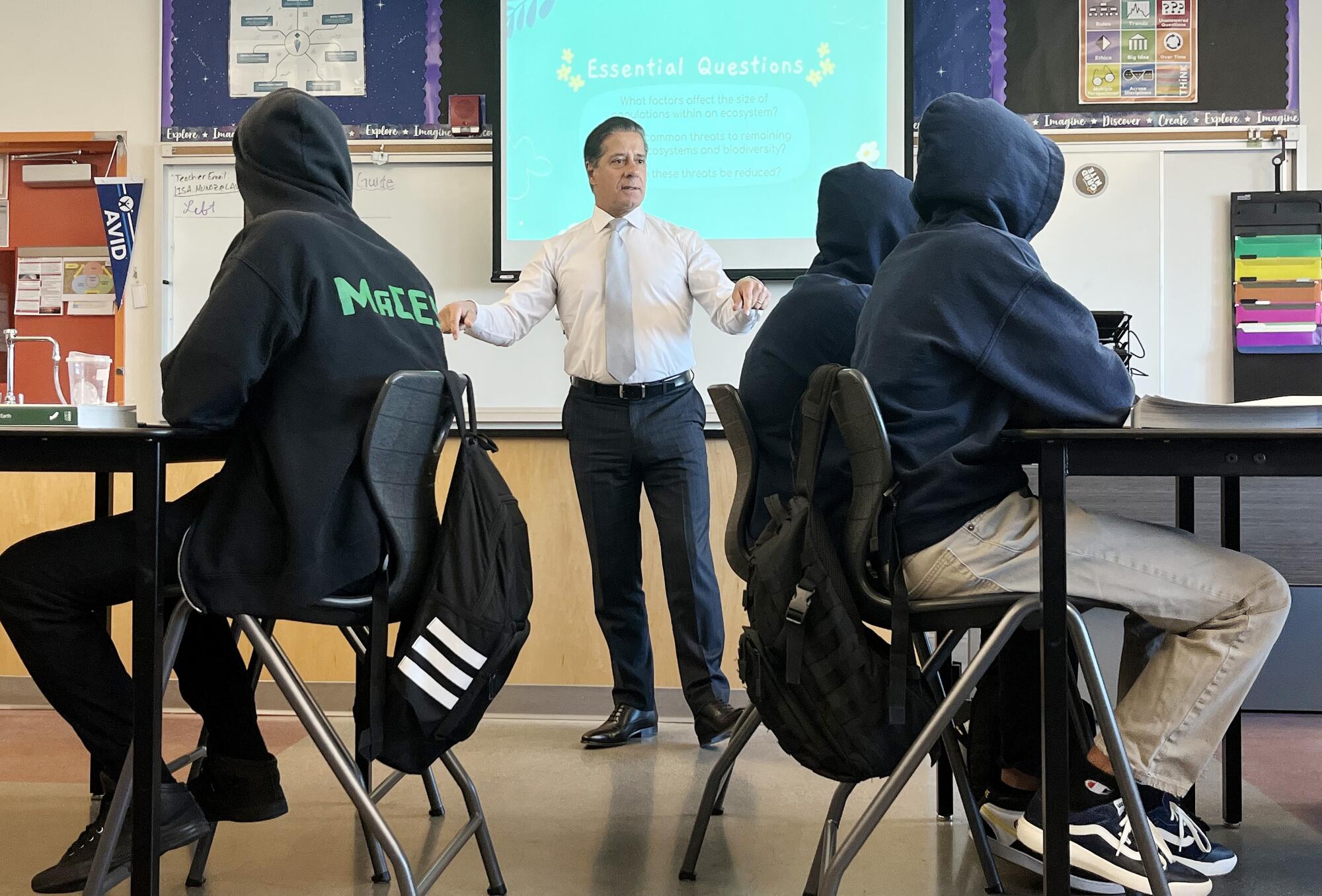

Exhilarated, he proclaimed “I love LAUSD” in sign language during a 125-mph skydive in a Twitter video. He posed on horseback in Topanga Canyon because connecting with nature is “indispensable to the holistic education of our students.” He has stood alongside Dr. Dre, George Clooney, Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore and Mayor Karen Bass. He has also been seen alongside first-graders, holding their hands, and with high schoolers, demonstrating how to extract DNA from a strawberry.

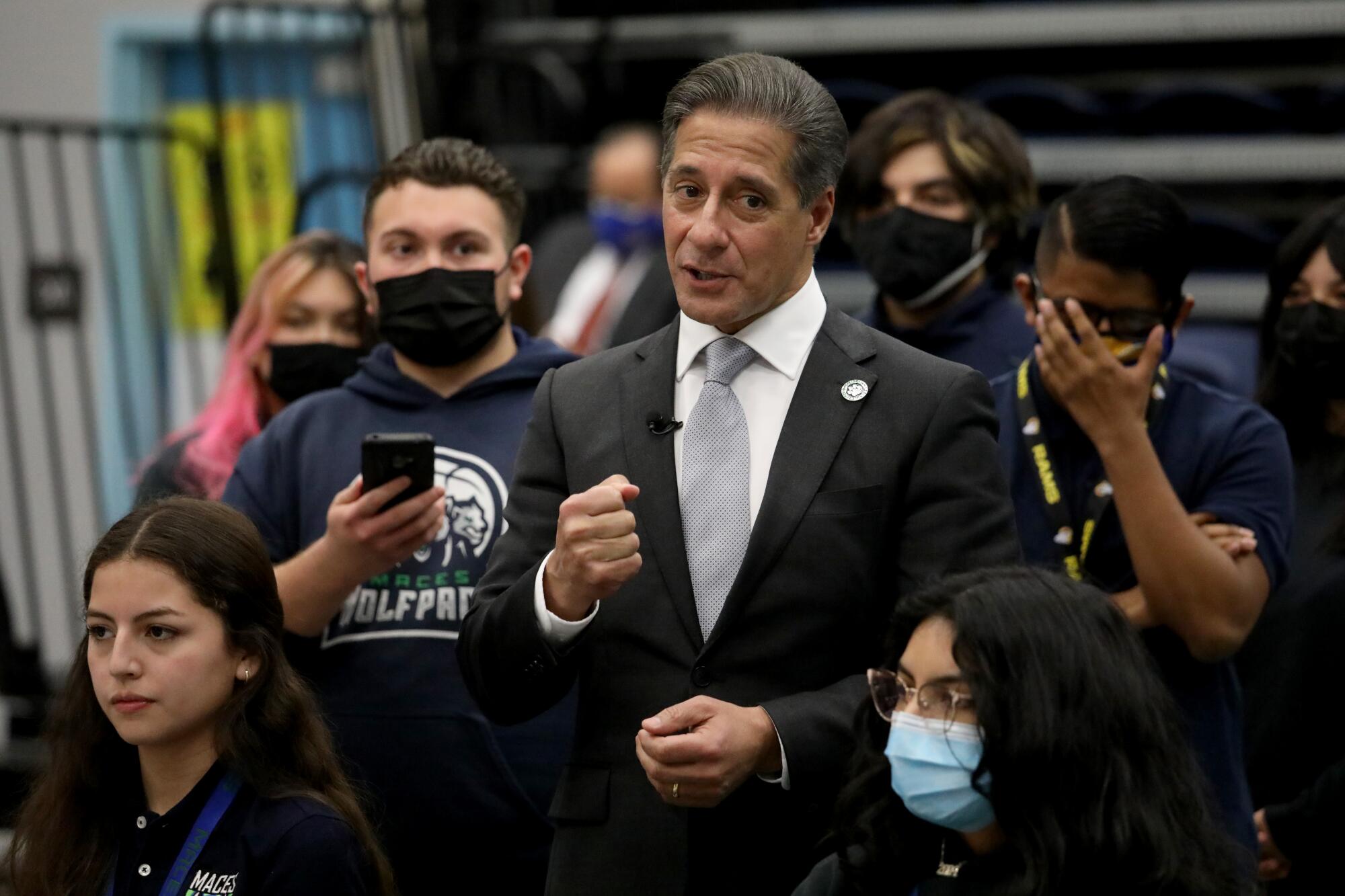

Los Angeles Unified Supt. Alberto Carvalho has curated a camera-ready persona and omnipresent social media profile as he completes his first year in charge of the nation’s second-largest school district, presenting a high-voltage style and bold agenda that evokes both applause and a few eye rolls.

Although it’s too soon to gauge progress, supporters are optimistic that Carvalho’s dizzying array of initiatives will begin to raise achievement for some 423,000 students following the brutal pandemic years. Since arriving from Miami-Dade, a district he led for some 13 years, Carvalho has earned generally high marks from education and community leaders and some advocacy organizations and retains strong school board support.

Confronted in the fall with standardized student test scores showing that five years of gains were wiped away during the pandemic, he pledged to make up two years of lost ground this year and the remainder in the following two. The target is aggressive at one level but still would leave lagging student achievement no better than it was before the pandemic. He has also predicted that long-declining enrollment — which threatens to weaken programs and close schools — will begin to rise under his leadership, despite what demographers have forecast.

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

The 58-year-old leader — sometimes introduced by underlings as “the most honored superintendent in American history” — also faces other challenges: planning for predicted budget shortfalls, defusing labor unrest and resolving a divisive debate over how to keep schools safe.

To guide the work, he developed a four-year strategic plan, approved in June by the board of education.

“Are we where we need to be? Absolutely not,” Carvalho said at a recent appearance at an elementary school in Watts. “Are we in a far better position than any other large urban district in America? Absolutely. Yes.”

Some parents, activists and community leaders have yet to be won over, saying he does not listen adequately to their concerns, tends to overstate his accomplishments or is less than candid about such issues as school safety and staffing. But criticism is muted, with most willing to wait and see, giving him credit for his ideas and exuberance — and also rooting for him, because as one put it, “His success is student success.”

“What’s great is that he’s been very confident and direct about what he believes needs to happen to make L.A. Unified the premier district in the nation,” said school board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin. “What’s been harder is the nuanced and humble leadership required.”

Among Carvalho’s first-year actions:

- Began a school-by-school data review process so principals know exactly where students stand.

- Added costly academic “acceleration days” to the calendar to give students a chance to boost grades and fill learning gaps. Critics called the first two days a failure, but not Carvalho, who intends to roll out an improved version during spring break.

- Rebooted tutoring after dismal participation in prior years.

- Filled teacher vacancies temporarily with former teachers who’d been promoted to nonclassroom positions.

- Sped up projects to add air conditioning and heating to work spaces in cafeterias and kitchens.

Some efforts were pilot projects, such as adding electric buses and, separately, setting up bus routes to help students avoid hostile gang territory or take advantage of after-school tutoring. Others were not fully ready when announced, including a mentoring program targeting 27,000 students and the creation of an “individual acceleration plan” for every student.

The gap raises questions about whether families are fully informed about the extent of their children’s academic setbacks and whether they are being well positioned to push for additional help.

Some events looked to some like publicity stunts, such as when he announced an LAUSD-branded care package for expectant mothers in a public hospital. He held up a “born to learn” infant onesie in a push to build future enrollment. The effort could better connect families to services, such as parenting classes and child-care assistance.

Along the way, Carvalho had to respond to two crises.

The district came under a massive cyberattack, detected over Labor Day weekend. Technicians swiftly shut down computer systems, probably preventing a catastrophic technology failure, according to some experts. Schools remained open, and the district pursued preventive measures to ward off future attacks, although Carvalho underestimated or underplayed the amount of disruption to district operations. Substantial problems lasted at least two weeks; some are ongoing. The board of education and meeting materials still must be accessed through a temporary website with limited functions.

The fentanyl-linked death of a student in September propelled Carvalho to move swiftly to provide naloxone — which reverses opioid overdoses — at every middle and high school, making the district a statewide leader in its response. But some worried parents say they are still waiting for data he promised on the number of student overdoses and crimes at schools — as well as a safety plan that combines drug treatment and prevention with appropriate law enforcement.

LAUSD acts in response to overdose death of student at school. Also will step up parent outreach and peer counseling.

Carvalho reiterated in an interview last week that he will work to make such data increasingly available, even at the cost of discomfort to some in the school system.

He promised six months ago that he would quickly deliver a comprehensive school safety plan but said there’s good reason for the extended timeline.

“For those who anticipate a report that strictly looks at police, they’ll be disappointed,” he said. “This is a holistic approach.”

Supt. Carvalho signals that he’ll support school police in response to parents’ concerns. Student activists demand defunding.

He listed what he means by this, saying his plan will take into account “community-based organizations, safe passage, early detection, training of students, community-based agencies that involve themselves with students, safe perimeter of schools, new technologies that address in-school threats, address the potential of external threats into the school, and really answer the questions that parents want to know:

“‘What are you doing about fentanyl? Do you have the appropriate partnerships? What educational programs are there? What are the means by which, anonymously or not, students and parents can convey information that prevents a crisis?’”

Last week, parents of students at Hollywood High and others, who testified to the school board in Spanish, presented a petition with 120 signatures calling for a return of school police to campus. Since campuses reopened in April 2021, officers have been limited to patrols and calls for service.

“I observed my daughter, and I talked to her friends, and the level of violence has increased all over,” said Cecilio Lopez.

In contrast, the prior week, student activists and their allies called for the complete dismantling of school police — illustrating the complexities that Carvalho must manage in a situation where every action or inaction will generate pushback.

Generally high marks

Several community groups and philanthropic leaders praised Carvalho, whose four-year contract pays $440,000 annually — $90,000 more than his predecessor, Austin Beutner.

“We have been most inspired by the superintendent’s team and his intentionality to prioritize instruction,” said Ana Ponce of the group GPSN.

“I’ve been really amazed at how he has managed to use the media as a means of projecting and communicating,” said Antonia Hernández, head of the California Community Foundation.

“We are inspired by the focus on family engagement, social-emotional learning and mental health services for students” in the strategic plan, said Elmer Roldan of Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, who added that “implementation on the ground is inconsistent.”

“Keep the pressure on and keep moving forward with what you have started,” Alicia Montgomery, chief executive of the locally based Center for Powerful Public Schools, said she would advise Carvalho. “I believe it will pay off.”

Four more school days, expanded transition kindergarten, better transportation offerings and ‘career labs’ are part of Carvalho’s plan.

Vocal parents and teachers in the 30,000-member Facebook group Parents Supporting Teachers have been less enthralled. Some described Carvalho as smart but questioned his trustworthiness. As an example, they pointed to his announcement to the press that 110,000 to 130,000 attended school over two “acceleration days” during winter break that were scheduled to give students an academic boost. Weeks later, without fanfare, the actual two-day attendance figure was revised down to 58,948, with 36,486 individuals attending one or both days.

Carvalho said the revised figures are more than enough to signal success, but that did not satisfy everyone.

“I’ve been disheartened by the PR lies ... which makes me doubt everything else he says,” said Rebecca Schenker, a parent of two elementary-age students in southwest L.A. “I like the excitement he can bring to a room — the politics are important to get us more resources. But I deeply dislike that the showmanship seems self-serving.”

Latino parents with the group Our Voice have criticized Carvalho for moving away too quickly, in their view, from strict safety protocols to protect against COVID-19. Some of these parents and others criticized Carvalho’s much-touted parent engagement as one-way — too much presentation and too little genuine exchange.

Carvalho seemed to respond to such criticism in remarks at the end of last week’s board meeting.

“I heard parents,” he said. “My door will always be open to an honest, respectful conversation.”

He said his own learning curve has involved grappling with the intricacies and diversity of Los Angeles, its neighborhoods and its constituencies.

“The multitude of advocacy entities can be bewildering to navigate, and it’s taken me a bit of time to be able to actually address them all,” he said. The loudest voices, he added, are not necessarily the most representative.

“I interpret this as good noise, as good trouble, as good positive pressure, that does nothing but improve our school system — to the extent that we’re able to filter that question of representation,” he said.

He has strong supporters among many parents, especially those who are critical of the teachers union or feel that the district was overly obsessed with health measures during the pandemic, at the expense of learning opportunities.

“Carvalho has been a much-needed student- and academic-oriented leader that has done a lot of community outreach,” said Christie Pesicka, a leader with the group United Parents Los Angeles. “Many families feel that their kids are represented for the first time in years.”

Labor woes

Leaders of the two largest employee unions paint a mixed picture amid increasingly intense contract negotiations. On Feb. 11, Local 99 of Service Employees International Union announced that members — including bus drivers, teaching assistants, custodians and cafeteria workers — overwhelmingly voted in favor of letting union leaders call a strike at their discretion. The union accused L.A. Unified — and, indirectly, Carvalho — of “blatant disrespect” of workers and violations of labor rules. The district denies this.

The teachers union also has not settled its contract.

Educators want a 20% raise but says they’re also committed to demands that represent the union’s social values, such as solar panels and electric buses.

“We’re not in Florida,” said United Teachers Los Angeles President Cecily Myart-Cruz. “We’re in California. We’re in Los Angeles. We’re ready for collaboration, and we’re ready for struggle.

“Our educators are not happy,” she added. “They’re seeing an outward-facing superintendent — that’s meeting with George Clooney or jumping out of airplanes and at the museums or riding on horses and a lot of flashy, showy things. And they’re not feeling the respect as professionals when there are very real issues happening on campuses that are not being addressed.”

Behind the scenes

The fundamental work of Carvalho’s superintendency may be taking place largely behind closed doors. He is substantially reshaping how the district is organized and who’s in charge, and what he does to elevate achievement and accountability at 100 schools designated as “most fragile” will be an important marker.

“I told this board I will assume responsibility for those schools directly,” Carvalho said.

“It’s been a good wake-up call for their school community to see their data in that way,” said Nery Paiz, president of Associated Administrators of Los Angeles, which represents principals and other midlevel managers. He added that the scrutiny has coincided with extra support, such as helping with campus greening and maintenance projects, specific staff training and filling vacant positions.

School board President Jackie Goldberg applauded Carvalho’s energy and activism, even if the exuberance is unfamiliar.

“He’s learning that there’s a different style here in Los Angeles than there is in Miami, a different way of using social media here, perhaps — and I think that he is a learner,” Goldberg said. “But he comes with a tremendous amount of knowledge and skill.

“We’ve never had a superintendent who took pictures of himself jumping out of an airplane before,” Goldberg added. “Some people thought that was terrible. Some people loved it, but it’s a different style. If that’s our biggest problem, I won’t be worried.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.