For lovers of true crime, gruesome tales of L.A. lovers’ lanes

- Share via

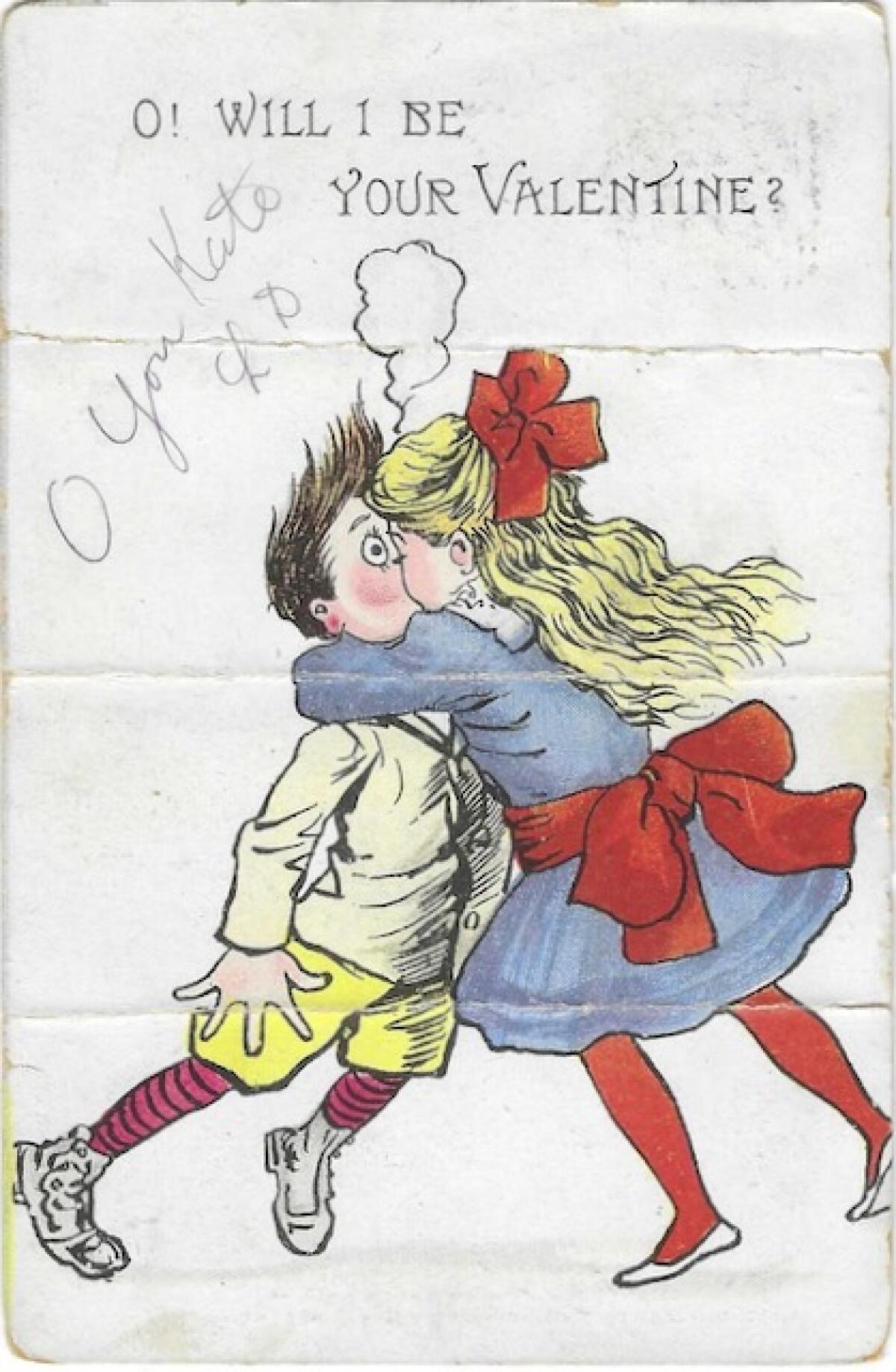

Choose your coy romantic euphemism for it: canoodling, spooning, necking, petting, courting or sparking.

But most apt — at least for us hereabouts — is “parking.”

No one could confuse it with the valet kind or the at-the-mall kind of parking; this is the parking that’s done in lovers’ lanes.

Lovers’ lanes predate the internal combustion engine by almost as long as furtive sex itself has been around. But once four-wheeled cubicles of sin began freeing couples from the scrutiny of the family front parlor, the moralists and divines queued up to denounce the automobile’s libertine liberties. A Catholic cardinal in Ireland in 1931 used his Lenten pulpit to bewail “the great and common source of evil — parking of motor cars close to dance halls in badly lighted village streets or on dark country roads.”

A year later, Los Angeles traffic cops had to remind wooing couples in their cars that it was a violation of State Vehicle Act section 136.5 to take both hands off the steering wheel. This was back when people used their left arms to signal lane changes, and officers had just ticketed a man who let go of the steering wheel to signal with his left hand — while keeping his right arm tightly clamped around his girlfriend. His car ran amok for 100 feet, but only his ego was injured when the incident made the papers.

As early as 1919, when California had about 415,000 cars, Santa Barbara authorities felt constrained to ban parking along the state highway for “billing and cooing” purposes.

“Any night, dozens of machines may be found parked by the roadside and dark, a menace to general traffic.” The news account was headlined “Back to Park Benches.”

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles, city of so many byways, took to cars and to “parking” with equal ardor. Yelp unsurprisingly lists rankings for Los Angeles makeout spots, and coming in at No. 5 — I’d have bet on No. 1 — is Mulholland Drive, with its dark turnouts above the light-jeweled carpet that is L.A. (It’s outranked by spots above the Hollywood Bowl, in Baldwin Hills, Universal City and a park in Culver City.)

As the TV detectives would say, parked cars offered means, motive and opportunity — for sex, yes, but for violence as well, putting the “lure” into the “allure” of lovers’ lanes, where engrossed couples are sitting ducks for robbery, rape and murder.

In recounting flivver-related felonies in the 1920s and ’30s, The Times was flippantly fond of smarmy turns of phrase describing parking couples as “worshipers at the shrine of the goddess of love” engaging in “roadside petting parties.”

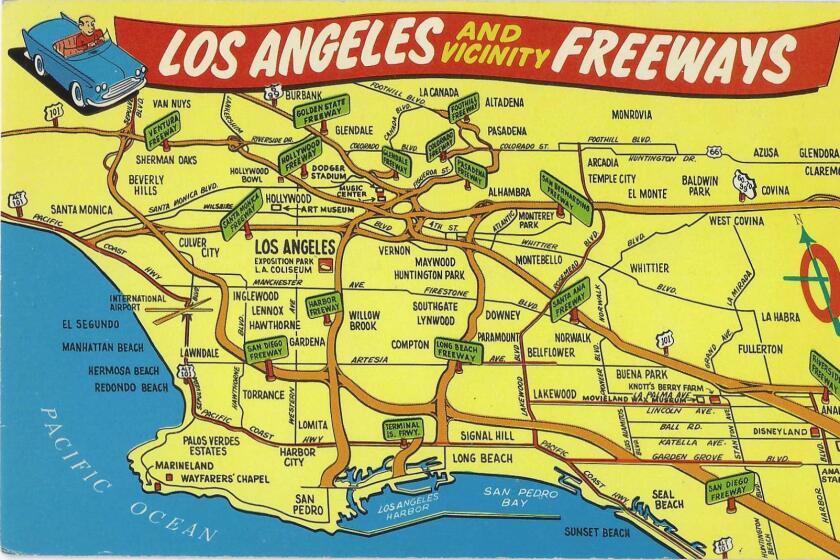

There is no Beverly Hills Freeway. Nor does the 2 connect to the 101. What even is the 90? These are the freeways that didn’t happen as planned.

But they made the news mostly when matters turned sinister.

In December 1960, in the oil town of Signal Hill, a teenager flashing a bogus police badge went around knocking on car windows and interrupting a dozen couples parked in the dark. Near midnight, he took a pair of Lakewood teenagers into “custody.” He handcuffed them and drove them around in their own car, even having the temerity to take the girl to her mother and deliver a lecture on the moral hazards of lovers’ lanes. The boy he released in Long Beach.

“Don’t let me catch you up there again,” he warned the boy, “or I’ll run you in for sure.”

In 1991, near the city of Industry, developers asked Los Angeles County to get rid of the “riffraff” lovers’ lane crowd and sell or privatize the road. A real estate broker railed, “You can go there any weekend day and in the broad daylight you can see buck-naked boys and girls” — he knew because he’d chased them off himself. But a sergeant at the local sheriff’s station said, meh, the kids are lovers, not fighters, and “generally it is not a problem for us.”

Other times, cops did try to shoo the kids away, for their own safety. In 1983, police came across a young couple necking in a car in Elysian Park and warned them that the area was dangerous. The couple didn’t leave, and some time later, three men stabbed the 17-year-old driver to death, then kidnapped and gang-raped his girlfriend.

Teens shivered at — but were not deterred by — the urban legend of the Hook, a murderous maniac on the loose, armed with a hook instead of a right hand. In the gruesome, tension-laced campfire tellings of this tale, usually delivered with sound effects, the killer either manages to lure the boyfriend out of the car and slaughter him, or the young people get unnerved hearing a radio report of the killer on the loose and hurriedly drive off — later to find a hook with a bloodied bit of arm attached hanging from the door handle.

The real lovers’ lane crimes should have been frightening enough to keep young lovers sitting across from each other at a malt-shop table.

In 1932, a Beverly Hills oil and real estate man — who you’d think could have afforded a hotel room — was shot to death parked in Laurel Canyon with an “attractive 30-year-old Venice matron.”

In June 1961, five couples parked near Ballona Creek were held up at gunpoint, and one man was shot as he fought the robber, who was carrying a .30 caliber carbine stolen not long before from the West Side National Guard Armory. (Police noted with unusual wryness of phrase that the lovers were “not in a settled frame of mind” at the time.)

In Encino in 1967, an armed man attacked a necking couple, tied the boyfriend’s hands and shoved him down a hillside and began to rape the woman. The boyfriend slipped out of his bonds, clambered back up the hill and fought off the attacker.

Nine years later, in a Boyle Heights lovers’ lane, two teenage girls whom police believed “may have rejected the advances of male acquaintances” were shot dead execution-style. The girls were neighbors and had gone to a party together earlier that evening.

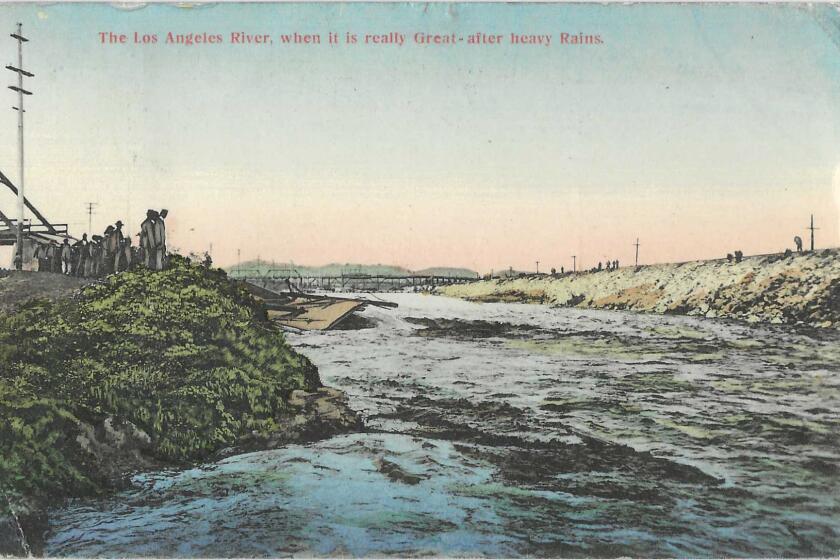

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

Honestly, some of the stories about lovers’ lane crimes were grotesquely salacious. From February 1959 in — I am sorry to say — The Times: “A comely brunet was found bludgeoned to death yesterday on a lovers lane in a sparsely populated area of the Verdugo mountains in Tujunga … the body, found stripped except for a pair of flaming red slacks and a white brassiere.” The victim was “a habitue of bars in several Southland communities.”

You achieve a critical mass of stories about any kind of crime, and Hollywood pays attention. Several TV shows and films have been built around lovers’ lane crimes, like a 1964 episode of the hipster show “77 Sunset Strip” and the exceptional 1995 Oscar-winning Sean Penn film “Dead Man Walking,” about an inmate sentenced to die for his part in the abduction and murders of two parked teenagers.

Lovers’ lanes were where the San Francisco Bay-area “Zodiac” serial killer found victims, as did New York’s “Son of Sam.”

One of California’s most notorious death penalty cases involved lovers’ lane crimes of robbery, rape and kidnapping. Caryl Chessman was one of the last men executed in California for a crime that did not involve killing another human.

The state’s Little Lindbergh law — passed after the 1932 kidnapping and murder of the renowned aviator’s son — allowed the death penalty for kidnapping and harming a victim. The “Red Light Bandit” had used a red light of the kind police use to stop couples driving in their cars — in one case, on Mulholland — rob them and, in at least two cases, force the women to accompany the robber, who sexually violated them.

Chessman’s conviction and death sentence, and his four books from death row arguing his innocence and critiquing the justice system, won him international attention from such well-known figures as Billy Graham, Ray Bradbury and Aldous Huxley. His case was such a source of anti-American sentiment abroad that in early 1960, the State Department got Gov. Pat Brown to issue a 60-day stay of execution so Chessman would not be put to death while President Eisenhower was visiting South America.

California repealed the Little Lindbergh law while Chessman was on death row, but the governor was by law hamstrung from commuting the sentence on his own, and Chessman died in the gas chamber in May 1960.

To end this on a note more befitting Valentine’s Day, spare a moment for Edward Berg. For at least eight years in the 1950s, he returned every March 24 to a San Bernardino lovers’ lane, where his teenage sweetheart, Angela Dornna, had once promised to meet him.

In 1952, the teens had met near the National Orange Show grounds and struck up a conversation and an affection. He was there with his father, an Air Force man soon to be assigned to Hawaii. She was about to go with her father to his new post in Bermuda.

They saw each other often for three months, and after they parted, she wrote to let him know that she’d find it hard to write to him but would keep their rendezvous in an Urbita Springs lovers’ lane where they had spent time together.

I found no mention of Berg after the eighth year of his vigil, when he was a high school teacher in Hyde Park, Ill., but come this March 24, if you find yourself in the Urbita Springs neck of the woods and see an elderly blue-eyed lady in a white dress or an old gentleman looking around expectantly for her, give them their private moment.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.