Brazen food stamp scammers steal millions from L.A.’s poorest. ‘They’re hemorrhaging money’

- Share via

The two men approached the ATM at 6 a.m. — soon after the state disburses the latest round of cash aid to the lowest-income Californians.

They sported dark clothing — one wearing paint-splattered black jeans and the other a zip-up and beanie.

For about eight minutes on the morning of Feb. 2, authorities say, they inserted cloned Electronic Benefit Transfer cards — the cards people receiving public benefits use to access their monthly funds — into the slot at a U.S. Bank ATM in Tarzana.

The beeps of the machine carried across the street as the machine dispensed stack after stack of other people’s cash.

For over a year, authorities say similar scenes have played out with increasing frequency in Southern California, as a ring of organized criminals has stolen people’s personal EBT card information and pilfered their accounts.

They strike early in the morning of the first few days of every month — hours, sometimes minutes after the state deposits benefits onto the cards. They do the same with food stamps, which the state also deposits on EBT cards, then rack up mammoth bills at grocery stores.

Some of the county’s poorest residents will wake up to discover a month of food or rent money they were relying on has vanished — even though their EBT card never left their wallet.

In Los Angeles County, officials say more than $19.6 million in EBT benefits were stolen in 2022 — a more than 20-fold increase from the year before, when the county lost less than $1 million. This January alone, the county lost over $2.9 million — a one-month record.

“They’re hemorrhaging money,” said L.A. County Deputy Dist. Atty. Alex Karkanen, who works in the public assistance fraud division, referring to the county. “It’s just got to be stopped.”

But no one quite knows how.

Some advocates and public benefit attorneys want the state to move faster to make the cards more secure, upgrading EBT cards to the chip or tap technology that is now standard on most credit cards. The L.A. County Board of Supervisors passed a motion last month asking the county’s Department of Public Social Services to lobby for cards with chips, which would make people’s personal account information harder to steal.

Jason Montiel, a spokesperson for the California Department of Social Services, said the agency is considering the technology but doesn’t have a timeline. The upgrade would require “complex technological and statutory changes,” he added.

Nicholas Ippolito, a bureau director for the county’s social services department, said he was told by the state it could take up to 30 months to upgrade EBT cards, which the county is “not very happy about.”

With more secure cards potentially years out, others are hoping to see a crackdown by law enforcement — intense enough to make people think twice about arriving en masse at ATMs during the first few days of the month. But Capt. Alfonso Lopez, commanding officer of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Commercial Crimes Division, said the crimes are too widespread.

“This problem is much bigger than any one agency can handle,” Lopez said. “This will not end purely through arrests.”

Nevertheless, on that Thursday morning, law enforcement attempted to make a dent.

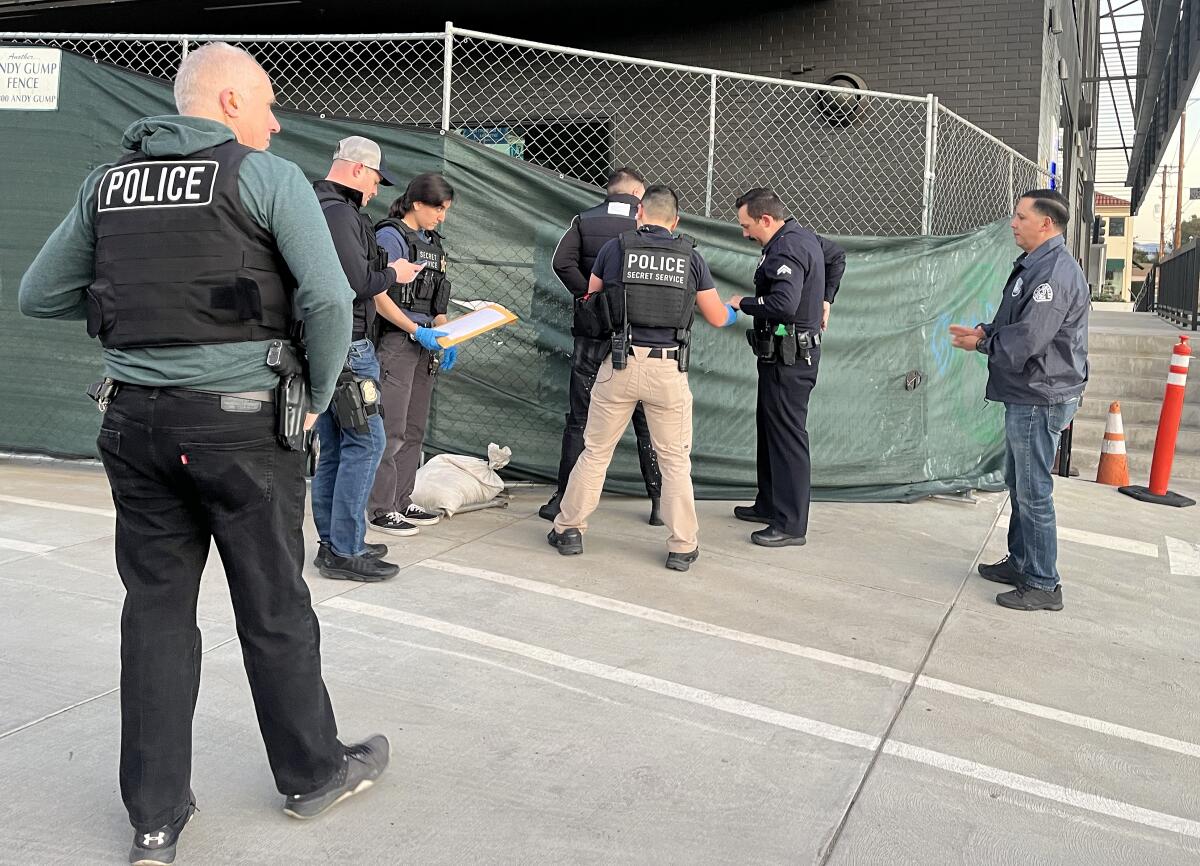

At 6:09 a.m., roughly a dozen LAPD officers and Secret Service agents descended on the quiet Tarzana street.

As they charged up the small flights of stairs to the cash machine, the two men put their hands up. A Times reporter witnessed the arrests, having gone to the ATM to observe after speaking with a victim whose funds were stolen there.

The two suspects remained stone-faced as they were led into the parking lot in handcuffs.

The police placed their newfound evidence on the ground: a patterned wallet, some cash and a half-dozen or so shiny cards.

Losing money with no support

Shaqueta Walker, 37, knows that ATM well.

She’s never actually been to it — or to Tarzana, for that matter. She lives more than 20 miles away. But twice in recent months, she said, she has looked at her EBT card transaction history and seen that very U.S. Bank branch listed — always next to a large withdrawal.

Every month, Walker gets $1,580 in cash aid deposited on her EBT card. She relies on it for groceries for her four children, school supplies and the occasional trip to Chuck E. Cheese.

On Nov. 2, she said she checked her statement and saw that a month’s worth of aid had been drained at the Tarzana ATM at 6:15 a.m. On Jan. 2, $1,580 vanished at 6:06 a.m. — the fifth time Walker’s funds had been stolen.

Walker rattles off the pilfered payments easily — she’s had to go over them so many times with police and county officials. In April 2021, $200 was taken in Sherman Oaks. In September 2022, $1,000 in Calabasas, then $300 in Canoga Park. Then twice at the Tarzana ATM.

She filed a police report after each theft, and shared them with The Times.

“I don’t feel protected and I don’t feel as if I’m really on this program because when benefits are taken from me, there’s no backup support,” Walker said. “When you’re a single mom of four children, you depend on every nickel.”

A full-time student at Pasadena City College, Walker receives both CalWorks, the public assistance program that provides cash to families, and CalFresh, which provides food benefits.

In California, people whose monthly benefits are stolen can be reimbursed. Recipients have 10 days after the theft to report their food stamps stolen and 90 days to report theft of cash aid. Counties then have 10 business days after the proper paperwork is filed to get people the benefits they missed, though the wait times have grown longer as the fraud proliferates.

Several fraud victims told The Times it took over a month and a half to get their money back.

Walker said she’s still waiting on over $3,000 worth of reimbursements from the county. In December, she was reimbursed $1,580 for the November loss.

Then someone stole that.

Last month, after the fifth theft, the state sent her a letter warning it might refer her for investigation of possible “EBT Card Trafficking.” Depending on what an investigation found, the note warned, she could be fined, jailed or have her benefits canceled.

Walker said she did not care much for the solution offered by a county social services staffer when she called for guidance on how to make the thefts stop.

“They told me, well, how about you just go to the ATM and as soon as your money hits, pull out your money?” she said. “And I told them, I said, ‘I’m a mother of four kids …. ‘ [They said] ‘Oh, well we have several parents that do that.’ ”

Janneth Queriapa, a mother of four boys, said she spent the final minutes of Jan. 1 waiting in her Nissan outside a bank near her San Bernardino County home for her CalWorks money to be deposited. As soon as midnight hit, she withdrew it all. She said she brought pepper spray on the off chance a fraudster showed up and tried to beat her to it.

Queriapa said $1,175 had been stolen the month before and that she could not afford for it to happen again. Though she eventually was reimbursed, she said the missing money led to $600 in late fees.

When Queriapa went to report the theft the following Monday at the social services office in Victorville, she said more than two dozen people were there to report that their benefits had been stolen at a U.S. Bank ATM in Gardena. She said many told her they had been hit around the same time, just after 6 a.m.

Queriapa said people sobbed as they grappled with what the thefts meant for their upcoming bills. Most vividly, she recalled a mother cradling a newborn.

“I could hear her saying to a social worker, ‘Look, I’m homeless with my kids. I’m a single mom. I need to pay the hotel for tonight. How am I supposed to pay for it?’ ” she recalled.

She said the mom was told to go to a shelter.

Lena Silver, with Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County, estimated that EBT fraud cases like these now make up a quarter of their caseload as the office advocates to get low-income people their stolen benefits swiftly reimbursed.

“It’s way beyond my pay grade or my understanding to try to understand why this is happening. Like who are these criminals?” Silver said. “How has this just ballooned so much that we’re seeing callers every day?”

Skyrocketing theft amounts

In 2019, Los Angeles County saw $25,227 in EBT benefits stolen, according to the Department of Public Social Services. In 2020, $340,891 was taken. In 2021, the number began to skyrocket: $914,003 was stolen, most of it in the last few months of the year.

Brian Krebs, a journalist who has written extensively about cybercrime, said these thefts are made possible by skimmers — difficult-to-spot devices that easily attach to legitimate card readers. They are usually placed on card machines in locations that people frequent weekly — convenience stores, ATMs and gas stations.

Skimmers are the closest an “average person is going to come to organized crime in their life,” Krebs said.

When shoppers make a purchase with their EBT card at one of these machines, the skimmer would retain both the card number and the PIN. In some cases, the people who surreptitiously placed the skimmer would return to the store days later to retrieve it in order to download the stolen data. Other times, it’s transmitted wirelessly.

They would then copy that information onto blank cards with magnetic strips on the back. Authorities say the ringleaders of the operation distribute the forged cards to people for start-of-the-month ATM runs.

On Sept. 1, an operation led by the L.A. County district attorney’s office staked out ATMs in the San Fernando Valley and central L.A. Prosecutors said they arrested 16 people at five ATMs, all of them Romanian nationals. Authorities confiscated over 300 fake cards and about $130,000 in cash.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Ryan Tracy, who prosecuted the cases, said everyone arrested appeared to be lower-level participants in a much bigger scheme.

All were charged with theft using a fraudulent card, a felony. Eight pleaded no contest and were sentenced to a month of community service and two years’ probation. The rest never showed up to court.

Several are believed to have returned to Romania. Karkanen, with the district attorney’s public assistance fraud division, said people are traveling to the region specifically from Romania to commit EBT fraud. The two men arrested last week — later identified as Cristian Chimirel and Petrisor Orbuletu — were Romanian.

Both were charged with fraud in federal court.

At their first appearance Monday, Judge Karen Stevenson said she believed Chimirel to be a “serious economic danger to the community.” Stevenson said he’s alleged to be in the country illegally and previously escaped from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Chimirel’s attorney, Carlos Iriarte, said he could not discuss the details of the case, which remains under seal.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.