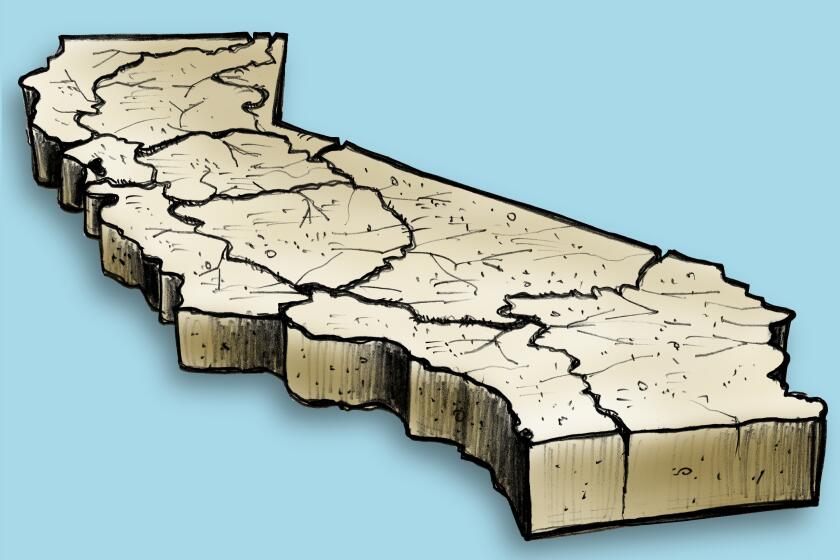

In a dramatic spike, 36.3 million trees died in California last year. Drought, disease blamed

- Share via

Roughly 36.3 million dead trees were counted across California in 2022, a dramatic increase from previous years that experts are blaming on drought, insects and disease, according to a report by the U.S. Forest Service.

The same survey for 2021 counted 9.5 million dead trees in the state, but the effects of last year’s dramatic die-off are more severe and spread across a wider range, according to the report released Tuesday.

The aerial report paints a bleak picture of a state ravaged by drought, disease and insects that feed and nest in thirsty trees. From mid-July to early October, researchers surveyed nearly 40 million acres, including federal, state and private land. They found dead trees spread across 2.6 million acres.

Douglas fir trees showed the biggest mortality rate increase. There were 3 million dead Douglas firs, an increase of 1,650%, counted across 190,000 acres, primarily in the central Sierra Nevada Range.

There were 12 million dead white fir trees, an increase of 691%, across 1.5 million acres, and 15 million dead red firs, an increase of 242%, across 890,000 acres. The dead trees were grouped mainly around the Northern California city of Redding, including in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest and surrounding areas.

The statewide results are alarming but not surprising to Ryan Tompkins, a forester and natural resources advisor at the University of California Cooperative Extension. Starting in early 2022, CalFire was sounding the alarm on tree mortality in Northern California.

“Going into the start of last year, it was a dry year,” Tompkins said. “A lot of people are saying, ‘Oh, my gosh, this is a big tree mortality year.’”

Drought conditions have exacerbated disease and insect infestations. Abnormally high temperatures and overcrowded forests choked with dead trees have also played a role in the increased mortality, according to forest officials.

In 2016, at the height of a historic drought in California, federal and state agencies counted nearly 62 million dead trees. The following year saw a drop to 27 million, and by 2019, surveyors counted 15 million.

The primary cause of mortality is drought. Roughly 80% of the state experienced severe drought conditions at the start of the year, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Thanks to a series of winter rain storms, the figure has dropped to 32%.

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

But forest officials say that the increase in dead trees will continue to be a problem for years to come as rain levels in general remain low.

Forest management will play a key role in how the state responds to tree mortality. The Forest Service’s 10-year plan to tackle the problem will include removing dead and dying trees in areas where they pose the most risk to surrounding communities.

Tompkins points out that drought and overcrowded forests create conditions for bark beetles and other insects to thrive. A healthy tree can repel a bark beetle, but the insects bore by the thousands into weakened trees, eating the bark and moist inner core, where nutrients are stored and transported from roots to needles.

“The real problem here is that our forests are far too dense. And when these forests are really dense, trees are competing for a finite amount of water, particularly in a dry year,” Tompkins said. “While we see these periodic droughts and these periodic tree mortality events, some of this is driven because we’ve normalized these very dense forests.”

A century of suppressing wildfires has created younger, denser, more uniform and more vulnerable forests, Tompkins said.

Northern California saw several deadly, fast-moving wildfires in 2022, including the Mosquito fire in Placer County and the McKinney in Siskiyou County. Northern California also saw more dead trees than other parts of the state.

As residential development has moved closer to forests over the past few years, wildfires, fueled by dead and dying trees, have destroyed more homes and structures.

Over the last 11 years, there has been a nearly 250% increase in the number of homes and other structures that have burned in the Western U.S. as wildfires have become significantly more destructive, according to a study published this month in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science-Nexus.

The primary takeaway is that more homes and outbuildings were destroyed in California by human-caused fires over a 22-year period.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.