Why Southern California water restrictions remain despite so much rain

- Share via

Call it water whiplash: As California recovers from one of its wettest months in recent history, the Colorado River is still dwindling toward dangerous lows.

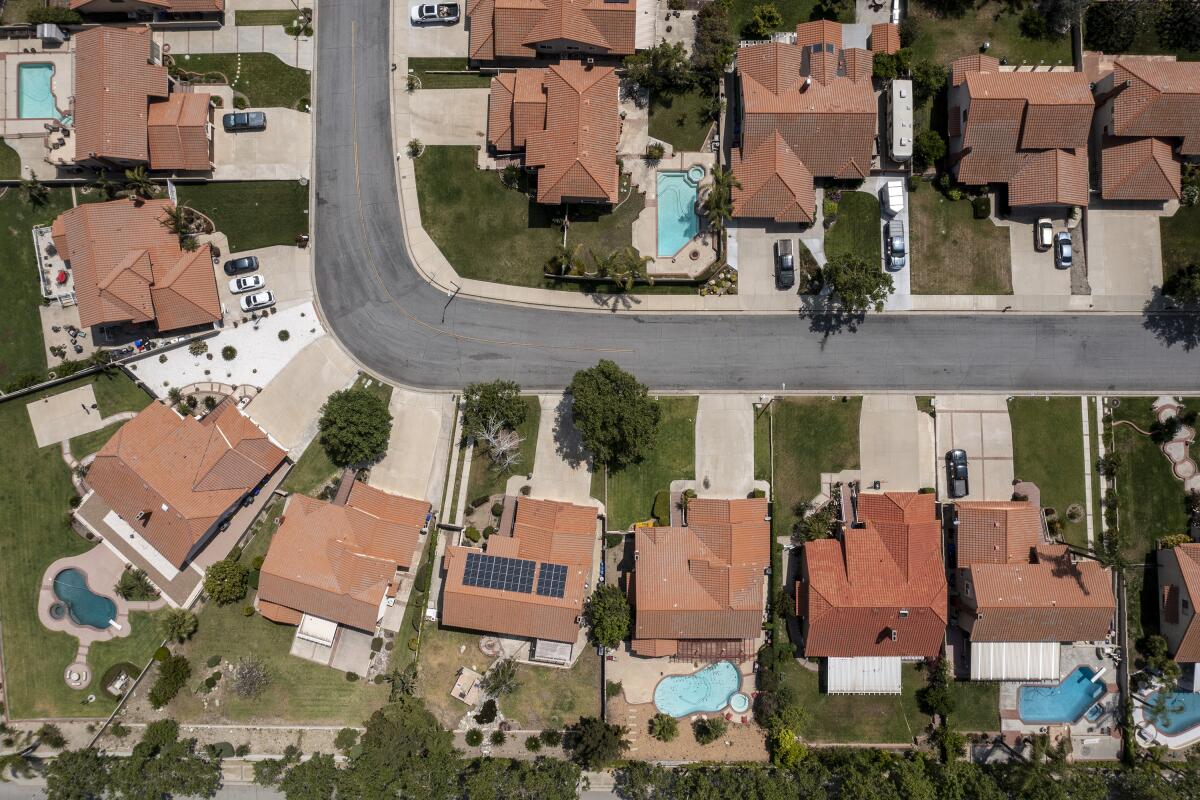

As a result, Southern Californians aren’t sure whether to expect shortage or surplus in the year ahead. Though the state is snow-capped and soggy from a series of atmospheric river storms, the region remains under a drought emergency declaration from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. That includes mandatory water restrictions for about 6 million people in and around Los Angeles.

The early-season storms provided some drought relief, but most officials say it would be premature to loosen water restrictions. In fact, the severity of the crisis on the Colorado — and the federal mandate that California and six other states significantly reduce their use of water from that river — means more calls for conservation are likely in the months ahead, according to MWD General Manager Adel Hagekhalil.

The wet start to the year “shouldn’t take the momentum away from us continuing to work on building resiliency, recycling water and storing water when we have it,” Hagekhalil said. “We should conserve as much as we can so we can save water to have it available when we need it.”

As the region wrangles over Colorado River water cuts, California hopes its senior water rights will trump the united front shown by six other states.

Hagekhalil said January’s burst of moisture was characteristic of climate change, which is driving huge swings between bouts of extreme wetness and extreme dryness. In 2022, a similarly strong start to the wet season ended with the driest January, February and March on record — meaning there’s no guarantee that the state will still be wet come spring.

“I don’t want to deal with the water supply in Southern California on a month-to-month, day-to-day basis,” he said. “I want to look at the long term, at how we can create a resilient water future for everyone, with no one left behind.”

The storms did provide enough of a boost for the Department of Water Resources to tentatively increase this year’s State Water Project allocation from 5% to 30% for its 29 agencies, including the MWD. The State Water Project is a system of reservoirs, canals and dams that is a major component of California’s water system.

For the record:

9:40 a.m. Feb. 6, 2023An earlier version of this article said incorrectly that Southern California gets about half its water from the Colorado River. Southern California gets about one-quarter of its water from the Colorado River.

But Southern California still gets about one-quarter of its water from the Colorado River, which didn’t really benefit from the storms and remains remarkably strained, Hagekhalil said.

He said MWD’s board will be evaluating the water supply between now and June to determine whether to upgrade Colorado River-dependent areas from their current voluntary 20% reduction to a mandated allocation — a move the agency made last year for State Water Project-dependent areas.

Though plans may change, MWD will likely aim for “uniformity across the whole region to ensure that we are all continuing to save, especially with what we’re seeing on the Colorado River,” Hagekhalil said.

At the heart of tensions over water allotments from the Colorado River is a complex set of agreements and decrees known as the ‘Law of the River.’

Some decisions also fall to individual agencies, which are often reliant on local conditions when it comes to their supplies. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power serves about 4 million people and receives some of its water from the MWD. Officials there never distinguished between Colorado River and State Water Project-dependent customers and instead last June placed their entire service area under two-day-a-week watering restrictions. DWP spokeswoman Ellen Cheng said Friday that while the recent storms were welcome, “the region’s water challenges are not over.”

“Reservoirs and storage within the state are still recovering, and impacts of Colorado River use reductions have yet to be resolved,” she said. “For now, L.A. is maintaining course with the current outdoor irrigation restrictions, and we are closely monitoring supply conditions as they continue to develop over the next couple of months.”

She added that DWP encourages customers to “keep their foot on the pedal” and continue to use water efficiently, including taking advantage of turf replacement programs to reduce water use.

Other areas plan to relax restrictions, however. The Las Virgenes Municipal Water District, which serves about 75,000 residents in Agoura Hills, Calabasas, Hidden Hills and Westlake, plans in the coming week to recommend to its board of directors a scaling back from Stage 3 of its water-shortage contingency plan to the less-restrictive Stage 2, spokesman Mike McNutt said.

Las Virgenes receives almost all of its supplies from the State Water Project and was among the areas hit hardest by reduced allocations last year.

If the move is approved, Stage 2 would loosen mandatory water restrictions and create a new districtwide target for a voluntary 20% reduction in water use, McNutt said. The district would also increase water budgets to what they were prior to the drought emergency and cease installing flow-restriction devices, save for potential cases of excessive and repeated overuse.

“In the past six months, our customers have averaged a 40% reduction in water usage compared to 2020 figures, which is remarkable,” McNutt said.

The agency is also moving forward with plans to construct a wastewater purification facility to reduce its dependence on imported supplies.

A water-strapped celebrity enclave that has long relied on imported supplies has taken a significant step toward water recycling.

At the Inland Empire Utilities Agency in San Bernardino, officials are more cautious about the months ahead. The wholesaler, which serves about 935,000 people, has since December been in Level 6 of its water-shortage contingency plan — the most severe level, reflecting a shortage of 50% of more.

“While the winter storms have provided us with some much-needed relief, our state is still facing considerable water supply challenges in the future,” General Manager Shivaji Deshmukh said in a statement Friday.

Deshmukh said the IEUA is working closely with the MWD to assess how the recent changes in imported supplies will affect the region.

“Although long-term impacts are still unknown, we believe that the increase in the State Water Project allocation will provide our customer agencies with supplies to better meet regional consumptive demands for the first six months of 2023,” he said. “Nevertheless, it is critical that we continue to work with and support our customer agencies on the implementation of their water use efficiency programs and assist in educating the community on the importance of conservation and the use of precious local supplies.”

Drought-weary California enters February with significant snowpack. But it could still disappear quickly if dry conditions return.

Such uncertainty is not unique to Southern California. Residents in all of the state’s 58 counties remain under Gov. Gavin Newsom’s drought emergency declaration, and state officials said it’s too early in the wet season to even consider lifting that order.

“We have a 30% State Water Project allocation, the Los Angeles Aqueduct system has great snowpack right now ... and then we have the Colorado River system, which is a question mark at this point,” Jeanine Jones, DWR’s drought manager, said during a news briefing this week.

Newsom first placed Sonoma and Mendocino counties under a drought emergency in April 2021, then added more counties in May and July before expanding the order to the entire state in October. Jones said that if and when the time comes, California will probably exit the drought emergency the way it came in — county by county, or region by region.

“We can talk about things like statewide snowpack, statewide runoff, statewide precipitation, but water supply is a local function, and it really comes down to what are the circumstances affecting a particular community or area,” Jones said. “Some areas will likely come out of drought conditions because of the very wet conditions that we’ve had, but it really depends on the circumstances of a water supplier’s individual sources of supply.”

Jones said groundwater, the state’s system of aquifers, remains severely depleted and could take years to recharge. Lake Mead and Lake Powell will similarly need more than one wet season to refill, she said, noting that the drought in the Colorado River basin began in 2000.

MWD’s Hagekhalil said the fragility of the system means that every drop is valuable, and the likelihood of an eventual return to dryness in California is all the more reason to conserve while water and snow are here.

“We cannot be just adapting to the rain and waiting for the rain,” he said. “This is bigger than all of us. The climate has changed, and we need to change.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.