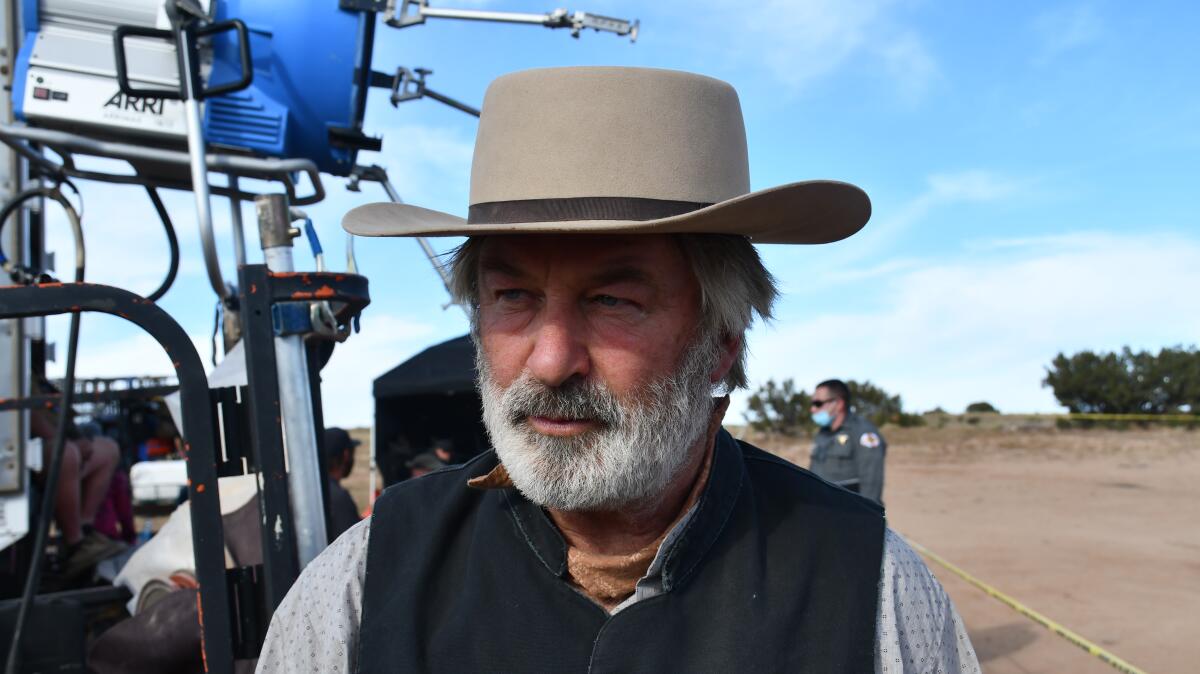

Key question at Alec Baldwin’s criminal trial: Is he to blame for Halyna Hutchins’ death?

- Share via

The criminal case prosecutors are filing against Alec Baldwin will turn on the same question that has dogged the actor since the day he shot cinematographer Halyna Hutchins on the New Mexico set of the film “Rust”: Is he responsible for her death?

Under New Mexico’s involuntary manslaughter laws, Baldwin could face up to five years in prison if a jury finds criminal negligence in his accidental firing of a vintage Colt revolver during the setup of a camera angle in October 2021.

Jurors will have to weigh whether he “should have known of the danger involved” when he pointed a loaded gun at Hutchins or “acted with a willful disregard for the safety of others.”

More than a year after “Rust” cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was fatally shot on the film’s set near Santa Fe, star-producer Alec Baldwin and the movie’s armorer are being charged in her death.

Baldwin’s attorney, Luke Nikas, said the actor “relied on the professionals with whom he worked, who assured him the gun did not have live rounds.”

Baldwin has long proclaimed his innocence. It was not his duty as an actor, he said, to ensure the pistol was not loaded with live ammunition, which is generally banned on movie sets.

Assistant director Dave Halls — who has agreed to plead guilty to negligent use of a deadly weapon — had told Baldwin that it was a “cold gun,” meaning its cylinder had been checked to ensure it was safe to use, according to the actor.

It was Hutchins, Baldwin said, who told him to point the gun at her as she was plotting a camera angle in a church on a ranch outside Santa Fe.

“I got countless people online saying, ‘You idiot, you never point a gun at someone,’” Baldwin told George Stephanopoulos of ABC News in December 2021. “Well, unless you’re told it’s empty, and it’s the director of photography who’s instructing you on the angle for a shot we’re going to do.

“And she and I had this thing in common, where we both thought it was empty, and it wasn’t. And that’s not her responsibility. That’s not my responsibility. Whose responsibility it is remains to be seen.”

Interviews with multiple members of the “Rust” crew paint an hour- by-hour picture of a cascade of bad decisions that created a chaotic set on which a lead bullet was put into a prop gun.

Mary Carmack-Altwies, the district attorney in Santa Fe, nonetheless laid some blame on Baldwin, announcing that charges against both him and the film set’s armorer, Hannah Gutierrez Reed, will be filed by the end of the month.

The district attorney plans to give the jury a choice between two involuntary manslaughter charges.

If Baldwin is convicted under the lesser charge, he would face up to 18 months in prison. If he is found guilty under the other one, which would require a finding of greater negligence, the mandatory penalty would be five years in prison.

The prosecutor’s decision came as no surprise to legal experts. “I can’t imagine a scenario where the person who fires the gun is relieved of any responsibility,” said Joshua Kastenberg, a professor at the University of New Mexico School of Law.

Beyond whatever facts the investigation uncovered, he said, the district attorney was facing political pressure to charge Baldwin in a case that has drawn enormous news coverage.

“As a D.A., you want to send a message ... that you don’t have two legal systems in your county — one for the powerful and one for everybody else,” Kastenberg said.

Baldwin is already fighting civil lawsuits accusing him of negligence for his shooting of Hutchins and “Rust” director Joel Souza, who was struck by the same bullet after it passed through Hutchins’ body.

“The idea the person holding the gun, causing it to discharge, is not responsible is absurd to me,” Matthew Hutchins, the cinematographer’s husband, said on NBC’s “Today” show after filing a wrongful-death suit against Baldwin, Gutierrez Reed, Halls and others. (Hutchins and Baldwin reached a confidential settlement last year.)

The standard of proof for civil liability is lower than for criminal conviction. Prosecutors must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the actor committed involuntary manslaughter, which in New Mexico is an unlawful killing of a person “without malice.”

One of the prosecution’s main challenges will be to prove that Baldwin showed “willful” disregard for others’ safety, Andrea Reeb, a former New Mexico district attorney, told The Times in an interview before she was named special prosecutor for the “Rust” case.

“‘Willful’ is a big word in there,” Reeb said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Baldwin has said he did not pull the gun’s trigger. But an FBI analysis of the pistol found that it “functioned normally when tested in the laboratory” and that in order for the gun to fire, the trigger needed to be pulled.

Manslaughter charges for accidents on movie sets are rare. Kastenberg teaches law students that manslaughter, with all of its nuance, can be harder to prosecute than murder.

“With premeditated murder, mostly you’ve got great evidence — someone confessed, or someone had a motive, and there’s blood on their hands, or there’s good DNA evidence, and there’s all sorts of behavior before and after the crime that helps you build the case,” he said.

In 1987, a Los Angeles jury acquitted director John Landis and four associates of involuntary manslaughter charges stemming from the 1982 deaths of actor Vic Morrow and two children in a helicopter crash on the set of the “Twilight Zone” movie.

But after a 2014 train crash in Georgia killed assistant camera operator Sarah Jones during filming of “Midnight Rider,” director Randall Miller pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter and served just over a year in prison.

Executive producer Jay Sedrish and assistant director Hillary Schwartz also pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter; they were sentenced to probation.

The filmmakers had decided to shoot a scene on a trestle that spans a river even after railroad track owner CSX denied them permission. A train zoomed into the set at 55 mph.

John Samore, a criminal defense attorney in Albuquerque, expects a clash of expert witnesses testifying about whether Baldwin’s conduct was in keeping with gun safety protocols that are commonly observed in the film industry.

Cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was killed on the set of “Rust” in October 2021. A judge dismissed the involuntary manslaughter case against star Alec Baldwin in July 2024.

Carmack-Altwies, the district attorney, told The Times that Baldwin “absolutely had a duty to either check the weapon himself or have someone check in front of him” and failed to follow film set protocols.

Several actors told prosecutors “that when you are handed a gun, you need to look at it and make sure that it’s safe,” she said.

A few weeks after Hutchins was shot, film star George Clooney said that the accidental shooting death of actor Brandon Lee on the set of “The Crow” in 1993 led many actors to start routinely examining a gun’s bullet chamber before using it in a scene.

“Every single time I’m handed a gun on a set, every time ... I look at it, I open it, I show it to the person I’m pointing it to, show it to the crew,” Clooney said on the “WTF with Marc Maron” podcast. “Every single take, you hand it back to the armorer when you’re done. You do it again. And part of it is because of what happened to Brandon. Everyone does it. Everybody knows. And maybe Alec did that. Hopefully he did do that.”

When Stephanopoulos played a recording of Clooney’s remarks on ABC, Baldwin snapped: “If your protocol is you check the gun every time, well, good for you. Good for you.”

Baldwin said he had been taught early in his career that filmmakers “don’t want the actor to be the last line of defense against a catastrophic breach of safety with the gun.”

“What is the actor’s responsibility?” Stephanopoulos asked.

“The actor’s responsibility is to do what the prop armorer tells them to do,” Baldwin responded.

Unless Baldwin strikes a plea deal, jurors at his trial will have to decide whether they agree with him.

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.