Appreciation: Pelé was the greatest soccer player. Was that good or bad for Brazil and for soccer?

- Share via

I saw the Brazilian soccer demigod Pelé play in person a few times and have watched innumerable clips of his greatest hits. Two of my most indelible memories are of goals that he didn’t even score.

Both occurred at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico City, where Brazil’s formidable Seleção was bidding for its third World Cup championship in a dozen years. No. 10 was in superlative form, as witnessed by two incidents of his wizardly audacity, his improvisational genius, his polyrhythmic joy.

In the semifinal against Uruguay, after snagging a breakaway pass from Tostão, Pelé drew out the Uruguayan keeper, then let the ball run to the goalie’s left while Pelé sped past on the right, retrieved the ball in a flash, looped back and just missed with a shot to the far post.

In Brazil’s 4-1 thrashing of a cynical and unimaginative Italian side in the final, seven Brazilians played keep away around midfield until the ball reached Pelé, who casually pushed it off to his right for a sprinting Carlos Alberto to apply the coup de grâce.

Brazilian soccer legend Pelé, who won a record three World Cup titles and helped popularize the sport in the United States in the 1970s, dies at 82.

In Brazil, where my wife and I lived for a few years, those dramatic moments (among others) have coalesced into a kind of secular catechism surrounding a sport that for Brazilians — and Argentinians, Mexicans and their Latin American neighbors — is far, far more than simply a national religion. Ever since fútbol was imported to this hemisphere more than a century ago, Latin America has not only radically reimagined the game and produced many of its brightest luminaries, but also has turned soccer into an escape hatch from poverty, racism and despair — in fantasy, if not often in truth.

This was the legend, the promise, that Pelé personified, and the dream of it dies hard in the slums of Buenos Aires, the dirt fields of Jalisco, the favelas of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Never mind that the contemporary sporting-industrial complex has converted promising young kids — especially Brazilian kids — into fungible units to be bartered and sold to high bidders in London, Paris and Barcelona. Even a tragedy like the 2019 fire that killed 10 young players at the Flamengo club’s training ground in Rio won’t stop the frenzy to “discover” the next Pelé, the next Maradona, the next Messi.

Pelé remains an aspirational figure for those young players. Yet he was no rebel like the other global superstars of his era. No Muhammad Ali, brandishing a fist at the Pentagon when it wanted to ship him off to Vietnam. No Jim Brown, the scourge of defensive backs and Black Power avatar bestride a motorcycle. No Billie Jean King, paddling the backside of male chauvinist piggery.

Pelé and his teammates had too much symbolic value for the brutal military junta that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985 to let them to be turned into counterculture heroes. That task fell to a later generation of Brazilians, including the great midfielder Sócrates, who helped lead the charge to return Brazil to democracy.

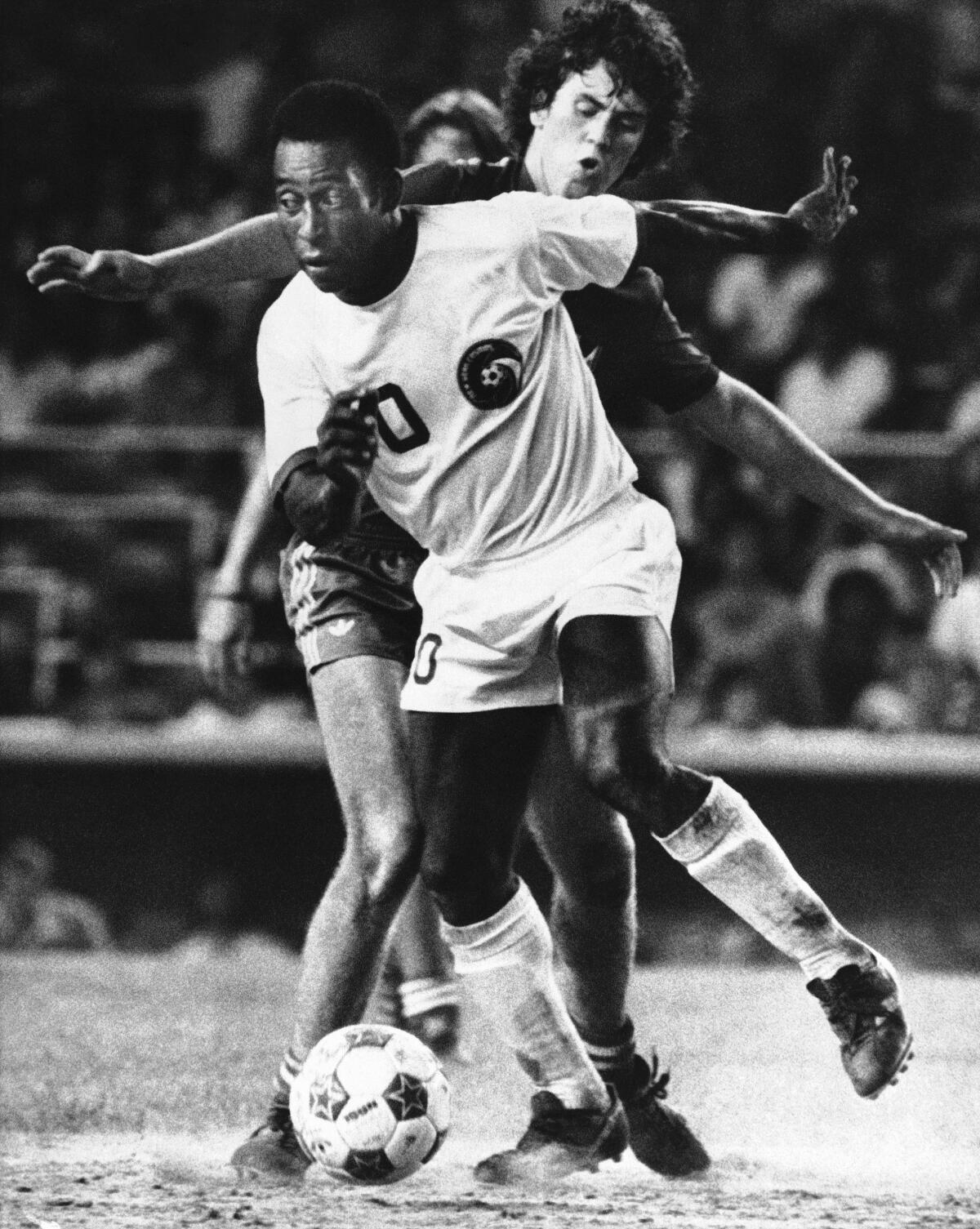

Pelé’s fate was to become a brand ambassador. I got to see him in person (though past his prime) on at least three occasions. In a 1970s exhibition game between his Brazilian club, Santos, and my benighted hometown Rochester Lancers of the benighted North American Soccer League, Pelé scored the only goal on a late penalty. A few seasons later, he and his new team, the New York Cosmos, set down the Lancers once more in the regular season and again in the playoffs.

Ostensibly, Pelé’s job with the Cosmos was to score goals. His real job was to soften up the world’s richest market, the United States, to embrace soccer. He succeeded at both.

I saw him one more time, as a pitchman for the 2014 World Cup, which Brazil hosted and got knocked out of in humiliating fashion. Soccer remains Brazil’s blessing and its curse, a glorious distraction from its daunting challenges and its dazzling potential.

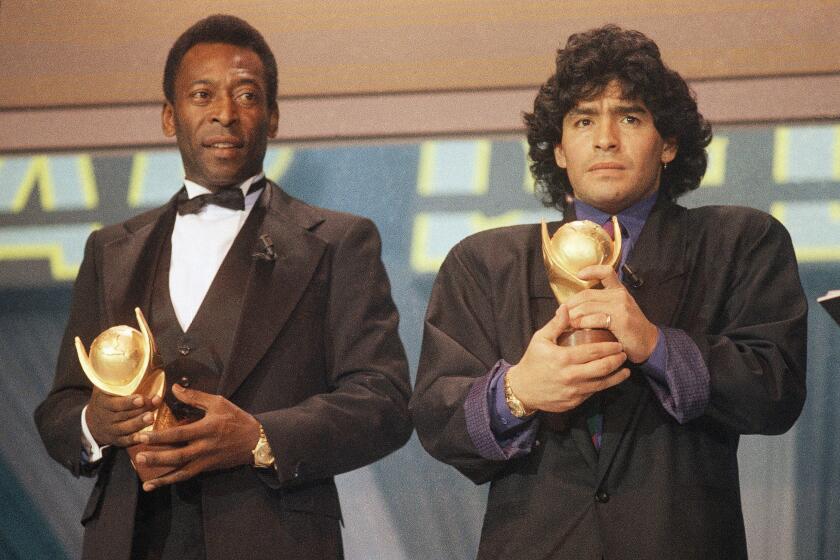

As soccer’s first global star, Pelé had an influence on the sport different from the stars that followed him, including Diego Maradona and Lionel Messi.

Pelé was a disrupter in the way that mattered most to him and to soccer: He expanded the limits of the possible. One wonders what he really thought about the pampered, preening, multimillionaire playboys of the contemporary global game, who change hairstyles weekly and win world championships sparingly. Pelé won two and easily could’ve won four in a row if not for an injury early in the 1962 World Cup in Chile (though Brazil still won) and a succession of ugly hackings during the 1966 World Cup in England (won by the host nation).

He was brilliant. He was unique. He was the best.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.