- Share via

Standing in the dappled sunlight of a Westside city park, Anthony Mazzucca was trying to make a point. The words flew out of him, like birds, a flock of words. He laughed at the thought.

Yet he wondered whether he was being clear. No one — not God, Obama, the devil, his counselor from high school — seemed to understand him.

It was the summer of 2015, and between the voices he heard and meth he had smoked, Anthony was once again slipping away.

Passersby might have seen just another homeless man talking to the trees. But in his mind, he wasn’t: He had a job as an incendiary non-pedophile informant for the FBI, and he had a home, Media Park off Venice Boulevard in Culver City. The cops left him alone, and his mother, Mary Liciaga, brought him food.

He was close with his family. He remembered standing up for a sister when she was bullied, giving money to another when she was broke.

“Now you don’t have to worry,” he had said, waving his hands over hers as if sprinkling coins.

But that was kid stuff. These were adult matters now — what with the demons in his brain, the strangers trying to poison him, the flying saucers, black widows and torture devices lying on the sidewalks.

He had tied himself to his bicycle with the belt to the bathrobe that he wore. He wanted to be ready when the other riders came and together they would fly through the night, city lights blurring around them until dawn.

A popular adage in psychiatry goes like this: If the human brain were so simple that we could understand it, then we would be too simple to understand it.

Anthony might agree. Ask him what it is like to live with schizophrenia and his reply is “dorsch,” and if schizophrenia is as incomprehensible as that, then its treatment for anyone who is homeless is even more baffling.

Since 2013, Anthony has been detained, hospitalized and confined at least five times. His family tried to intervene and manage his symptoms, but the volatile nature of his condition and the cost of treatment made it impossible.

“The mental health care system in L.A. County, like almost every jurisdiction in our nation, is broken badly. I could spend my whole career trying to fix what’s wrong here in L.A. and still not succeed.”

— Dr. Jonathan Sherin, former director of mental health for Los Angeles County

Deemed a danger to himself and to others, he passed through a system that helped him when he was in extreme distress but was unable to provide consistent, long-term care. For six years, nearly two dozen agencies — from the San Fernando Valley to the San Gabriel Valley, from the Westside to Long Beach and downtown Los Angeles — got involved.

When he was severely psychotic, he was hospitalized. When he was medicated, he was sent to an acute-care facility. When he was able to care for himself, he was sent to a board-and-care, where he went off his medications, began taking drugs and ended up back on the streets, vulnerable to the next psychotic episode.

His experience is far from unique.

“The mental health care system in L.A. County, like almost every jurisdiction in our nation, is broken badly,” said Dr. Jonathan Sherin, former director of mental health for Los Angeles County. “I could spend my whole career trying to fix what’s wrong here in L.A. and still not succeed.”

By some estimates, close to 40% of people living on the streets are experiencing severe mental illness, a substance abuse disorder or both. More precisely, the California Policy Lab at UCLA counts just over 4,500 people living on the streets of the county who have a psychotic disorder like schizophrenia, and that number includes only those who have received outreach services.

“Many are not connected to services,” said Janey Rountree, the group’s executive director, “and they are even more vulnerable and in need of help.”

Ever since the state hospitals were shuttered in the 1970s, California has tried to make up for deficiencies in its care of mentally ill individuals.

In 2002, Laura’s Law allowed for court-ordered outpatient treatment. In 2004, the Mental Health Services Act added funds to mental health facilities and programs. More recently, Proposition HHH and Measure H brought more money and resources for homeless people to the city and county of Los Angeles.

Now, the CARE Act, signed into law in September by Gov. Gavin Newsom, promises to mandate treatment and housing for those unable to care for themselves.

The legislation will put in place an infrastructure to provide services to a projected 12,000 of the state’s most vulnerable residents for up to two years. It has been hailed as a major transformation in how the state addresses mental illness.

But Anthony’s story over the last 10 years is a caveat for the state if it intends to end the epidemic of mental illness on the streets. Existing treatments and services can ease the immediate distress of severe mental illness but don’t go far enough in helping individuals like Anthony commit to long-term recovery and return to their communities.

During each step of his treatment — from psychiatric wards in some of the county’s best hospitals to the board-and-care facilities that are the hope for long-term housing — he had opportunities to stabilize and heal from the worst of his symptoms. None of that kept him from cycling through the system time and again.

A challenging patient, Anthony tested the facilities that treated and housed him, and they were unable to keep him engaged in his recovery.

“It feels like a battlefield. I want to leave, but I can’t leave my son, and I will not have him stepping foot by himself in this city again.”

— Mary Liciaga, Anthony’s mother

Pressured by overcrowding and a chronic shortage of suitable psychiatric placements, providers release patients like Anthony — once improvement is seen — to community-based settings that are ill-equipped to give them the treatment and long-term support that might lead to independent living.

For more than three years Anthony has lived at Meadowbrook Behavioral Health Center, a locked facility in West Los Angeles, his worst symptoms kept in check by medication. The cost of his treatment is covered by a range of government agencies and programs, including the county Department of Mental Health, Medi-Cal and the federal Supplemental Security Income benefit Anthony receives as a disabled adult.

Interviews with Anthony, his family and mental health professionals, along with a review of his medical records, demonstrate not just the bewildering nature of this condition, but also the helplessness with which it leaves families. Meadowbrook’s administrators declined to speak to The Times.

A Times reporter and photographer spent months chronicling the life of a man living with schizophrenia.

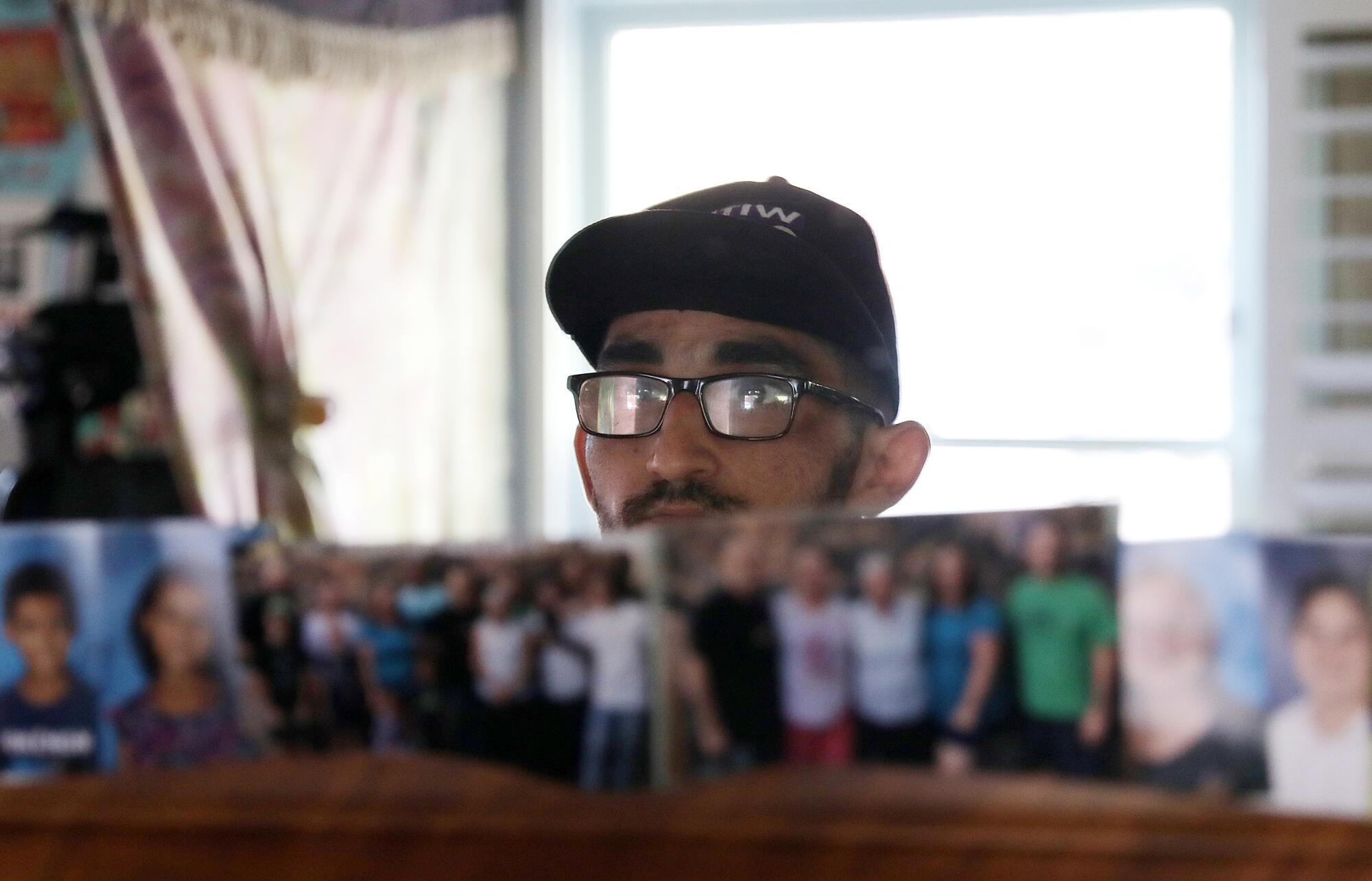

Mary, who is Anthony’s conservator, lives close to Meadowbrook and drives past a cluster of tents beneath the 405 Freeway whenever she visits, a reminder of how vulnerable her son is to the street.

He is 31, and she wants to take him out of Los Angeles. She has family in rural New York, and Florida is also an option. Anything, she hopes, would be better than here.

“It feels like a battlefield,” she said. “I want to leave, but I can’t leave my son, and I will not have him stepping foot by himself in this city again.”

So many thoughts and memories, invited and uninvited, fill Anthony’s head.

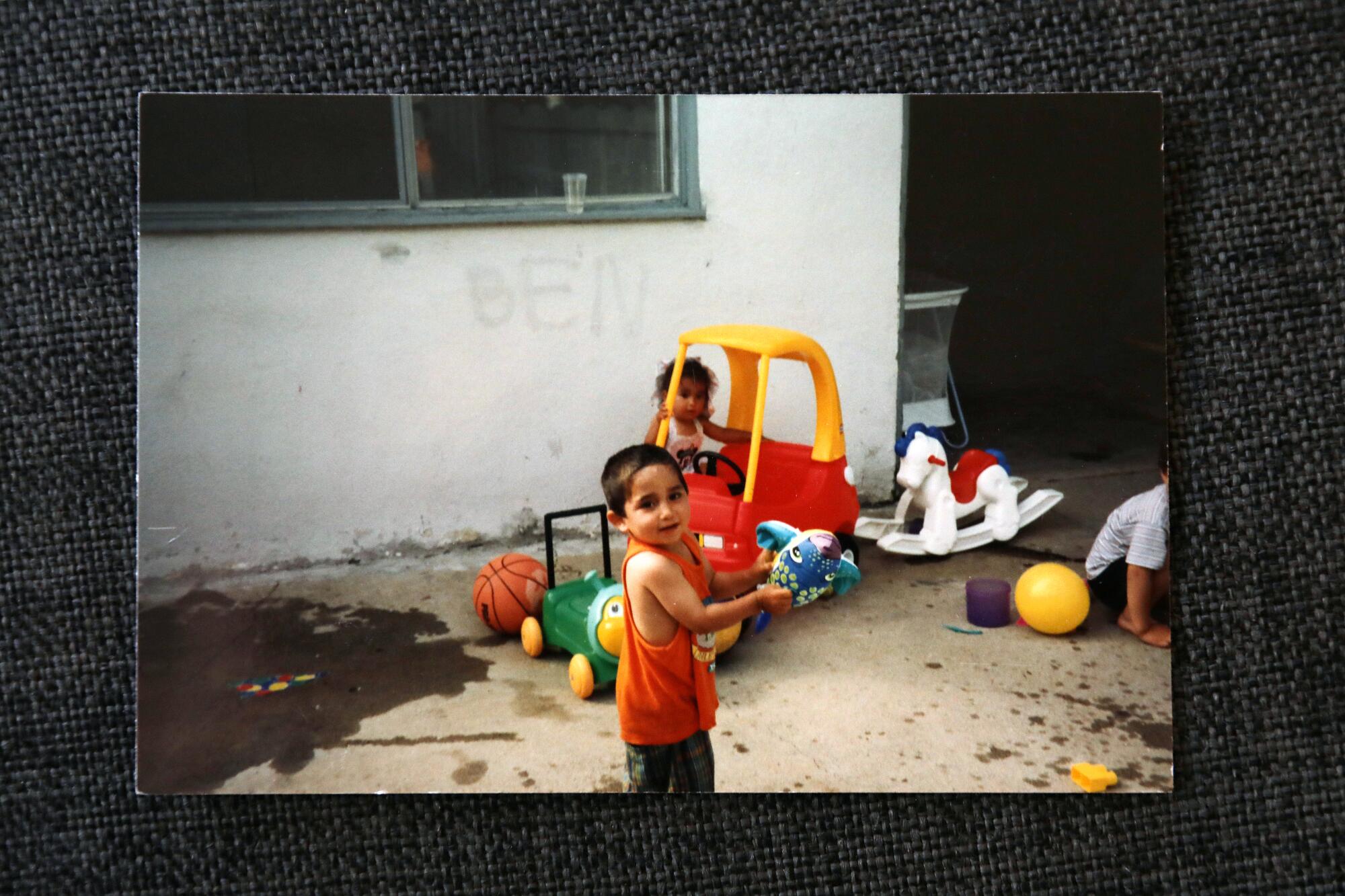

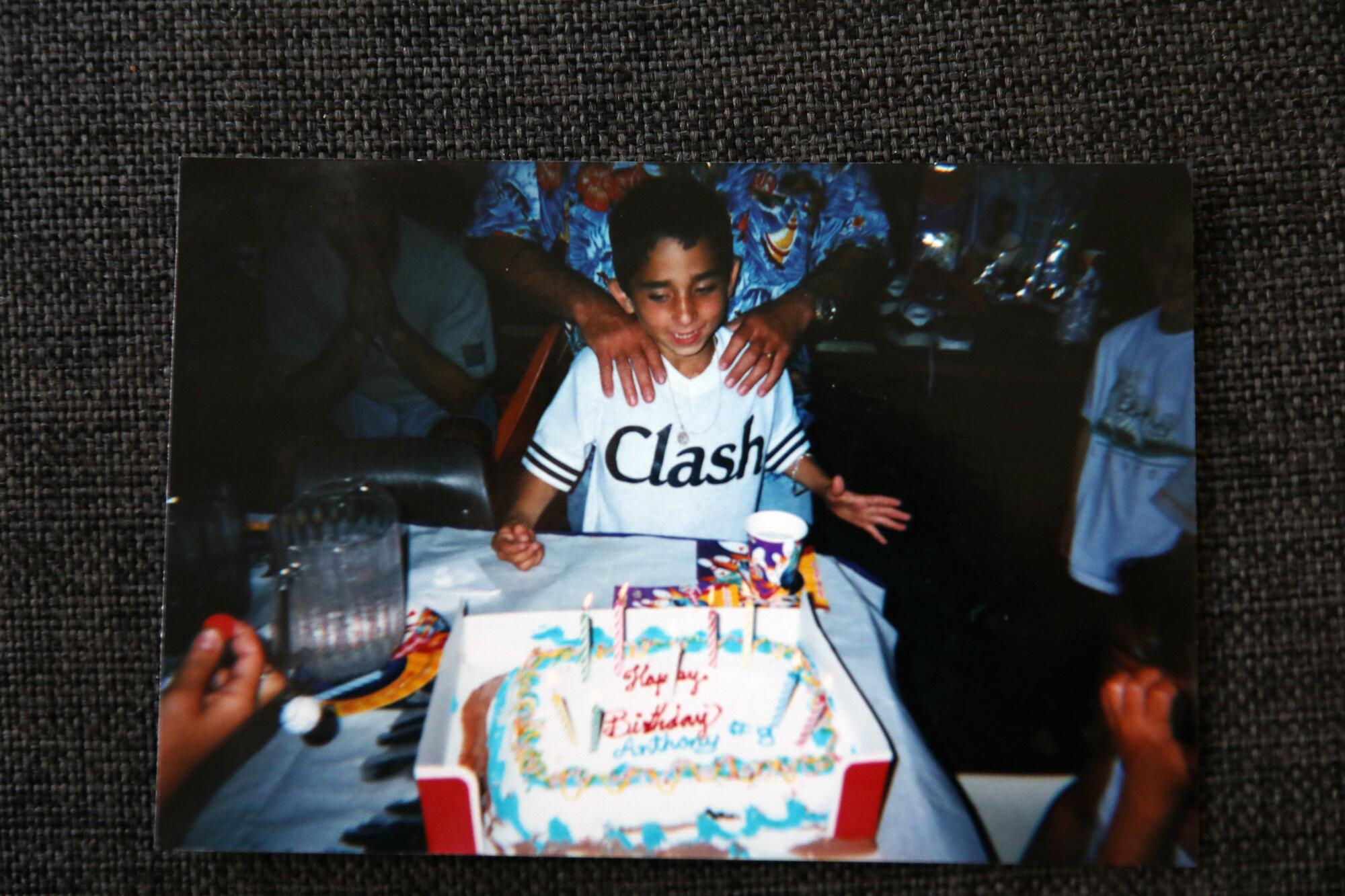

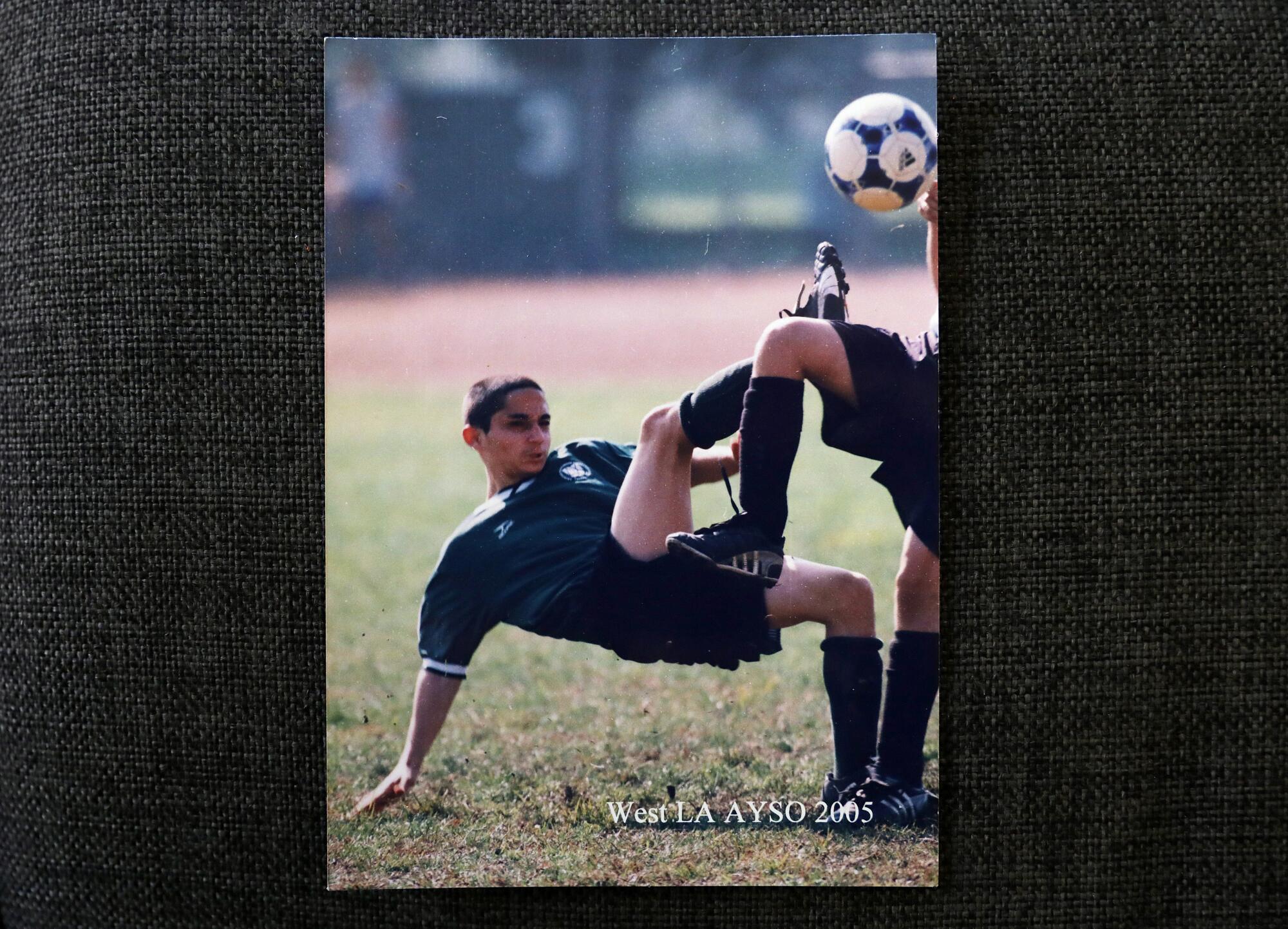

There he is: a boy running with his soccer team during matches, a teen laughing and smiling with his grandmother in her wheelchair, a young man feeling the warmth of the sand on summer days at Venice Beach with his three sisters beside him.

But shadows fall on the sunny images. His family moved around the country: New York, California, Arizona. Drunk or high, his mother and father fought. Skirmishes left her, Anthony and his sisters bruised, both parents recall.

Mary got sober when Anthony was 7, and a few years later, his father, Anthony Sr., left them. He says he regrets losing touch and is trying to stay connected to their lives.

With help of a local agency, his mother found a hotel room above the Venice boardwalk. Anthony slept in a sleeping bag on the floor.

She eventually moved into a two-bedroom apartment in Palms and started working as a cashier. She met Dan Williams, who was also in recovery. The 12-step program became their religion, but Anthony never came to the altar.

A short, skinny kid with glasses growing up in a tough neighborhood, he survived by playing the prankster. Sometimes he crossed the line: taking a BB gun to school after a classmate punched him, blowing up a car with an M-80 placed near the gas tank.

He started getting high, too: pot at 9, methamphetamine at 14.

A few years later, he threw a 40-ounce beer bottle at a probation officer. He was arrested, and Mary refused to bail him out.

He went to a group home in Van Nuys and another in San Diego County, and after nine months, returned to West L.A., renting a room from a friend and working at a bike rental in Santa Monica. He was 20.

Every week he flew through the streets of the city on his fixed gear with nearly 200 other riders.

Then he began hearing voices.

Schizophrenia typically emerges after adolescence with personality changes that erase some capabilities, behaviors and memories while retaining others.

The break between past and present can be disorienting. Memories mix with delusions. Psychotic episodes, the worst of its symptoms, are especially terrifying. A tree, a street, a face lose context and meaning. In the absence of understanding, the imagination fills in the blanks.

“Every sight, every sound, every smell coming at you carries equal weight; every thought, feeling, memory and idea presents itself to you with an equally strong and demanding intensity,” Elyn Saks, a USC law professor and MacArthur Foundation fellow, wrote in a 2007 memoir detailing her experience with schizophrenia.

“It’s the crowd at the Super Bowl, and they’re all yelling directly at you.”

To help someone in psychosis, one psychologist says, it’s best to first just be there and listen.

Researchers believe they have traced the illness to misdirected electrical impulses in the brain, arising from a loss of brain tissue caused by genetics, the environment or both.

Some people with a strong genetic likelihood of illness may develop schizophrenia regardless of what happens in their lives. For others, “certain stressors may be associated with earlier or more severe illness,” said Dr. Alaina Burns, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA.

Stressors may include viral illness during pregnancy, the effects of poverty and racism, neglect or abuse during childhood. Chronic use of marijuana at an early age has been implicated, as has abuse of methamphetamine.

Addiction can be a contributing factor as psychotic disorders make impulse control difficult and substance use becomes a compulsion. That’s especially true among people living on the streets, where the use of drugs is rampant, leading to psychoses that are especially difficult to treat.

“Methamphetamine use can cause psychotic symptoms without schizophrenia being present,” said Dr. Larissa Mooney, an addiction psychiatrist at UCLA who studies the intersection of substance use and mental illness. “And it can also exacerbate or worsen the underlying symptoms of schizophrenia when it is present.”

Untangling the connection between substance disorders and schizophrenia is particularly challenging if someone is cycling in and out of an inpatient setting, Mooney said.

Both Burns and Mooney believe that schizophrenia can be treated given time and patience. Burns, who runs a treatment program, describes patients who have jobs, spouses and children. Many of those don’t disclose their diagnosis due to the stigma of the condition. Others require lifelong care.

“There is no one illness called schizophrenia,” said Burns. “Two people with schizophrenia may have completely different presentations and prognoses.”

Mary and Dan knew something was wrong. Anthony had started making strange sounds and gestures with his hands. One day he accused them of poisoning his coffee.

At first, they thought he was getting too drunk or too high, which was unacceptable in a household that maintained its distance from alcoholism and addiction through discipline and Christian devotion.

Mary wanted him to take responsibility for himself. Dan gave him work, simple construction like laying tiles, but Anthony lost focus and wandered off.

One day when he was home, Mary caught him looking at an old photograph of himself.

“I miss that Anthony,” she recalled saying.

“So do I,” he said, crying.

Early in 2013, he had his first hospitalization. He was 22. He had been standing in the middle of Venice Boulevard and was nearly hit by a bus. After a psychiatric evaluation, he was placed on an extended involuntary hold and transferred to Gateways Hospital and Mental Health Center near Elysian Park.

Once discharged, he moved in with his father but stopped taking his medications and was soon delusional. On one occasion, he said he found diamonds in the street. He held the stones in the palm of his hand, and they glittered in the light.

“Look,” he said to his father, who recounted the incident, “now we can get a big house and all live together.”

A list of crisis hotlines, low-fee and sliding scale counseling, support groups, and mindfulness and meditation services

Anthony Sr. studied them. They were pieces of a broken windshield. When he threw them in the trash, Anthony took a swing and dislocated his father’s shoulder.

He later tried to jump from a moving car. Police drove him to the emergency room against his will, and for the next 14 months he was confined to locked facilities.

His medical records would soon fill the shelf of a library. One facility — Kedren Community Health Center — documented his behavior three times a day for nine months through June 2014:

Mr. Mazzucca presents with a labile mood and a flat affect. His thought process is disorganized with a low content. He is isolative, withdrawn, hyper religious, internally preoccupied, guarded and suspicious.

At Kedren, he was assigned a public guardian and eventually transferred to a facility on the Westside, Meadowbrook, where he successfully appealed his involuntary commitment and moved into an unlocked, 185-patient board-and-care home in Pico Rivera.

Supervision was minimal, and Anthony could walk to a nearby shopping center and panhandle. He would buy beer and cigarettes, even methamphetamine and cocaine, according to toxicology reports cited in records provided by the county Department of Mental Health.

He again went off his medications. He stopped sleeping, stopped wearing shoes. Once he ripped the handle off the door, frightening his roommate.

“I am God. I am the devil,” he declared. “I’m saving the world.”

A response team from the county Department of Mental Health was called in but did not recommend an involuntary hold. He was “oriented,” they reported, denied being suicidal or homicidal, and could identify “how to have his daily needs met.”

Four months later, the team came to a different conclusion. Sheriff’s deputies had cited Anthony for violating Pico Rivera’s municipal code that bans “soliciting food, clothing, alms in any public place in the city or from any person.”

He had gotten worse: acting belligerent, pushing people, stalking a bank employee for cash. “I’m going to squeeze you like a bug,” he said.

He was taken to L.A. County-USC Medical Center and transferred to Mission Community Hospital in Panorama City. Ten days later he was discharged “with bus tokens and a list of homeless shelters,” as Mary recalled, and showed up at her door.

He stayed until Mary and Dan kicked him out for bringing drugs into their home. He moved to Media Park, where he began talking to God, Obama and others.

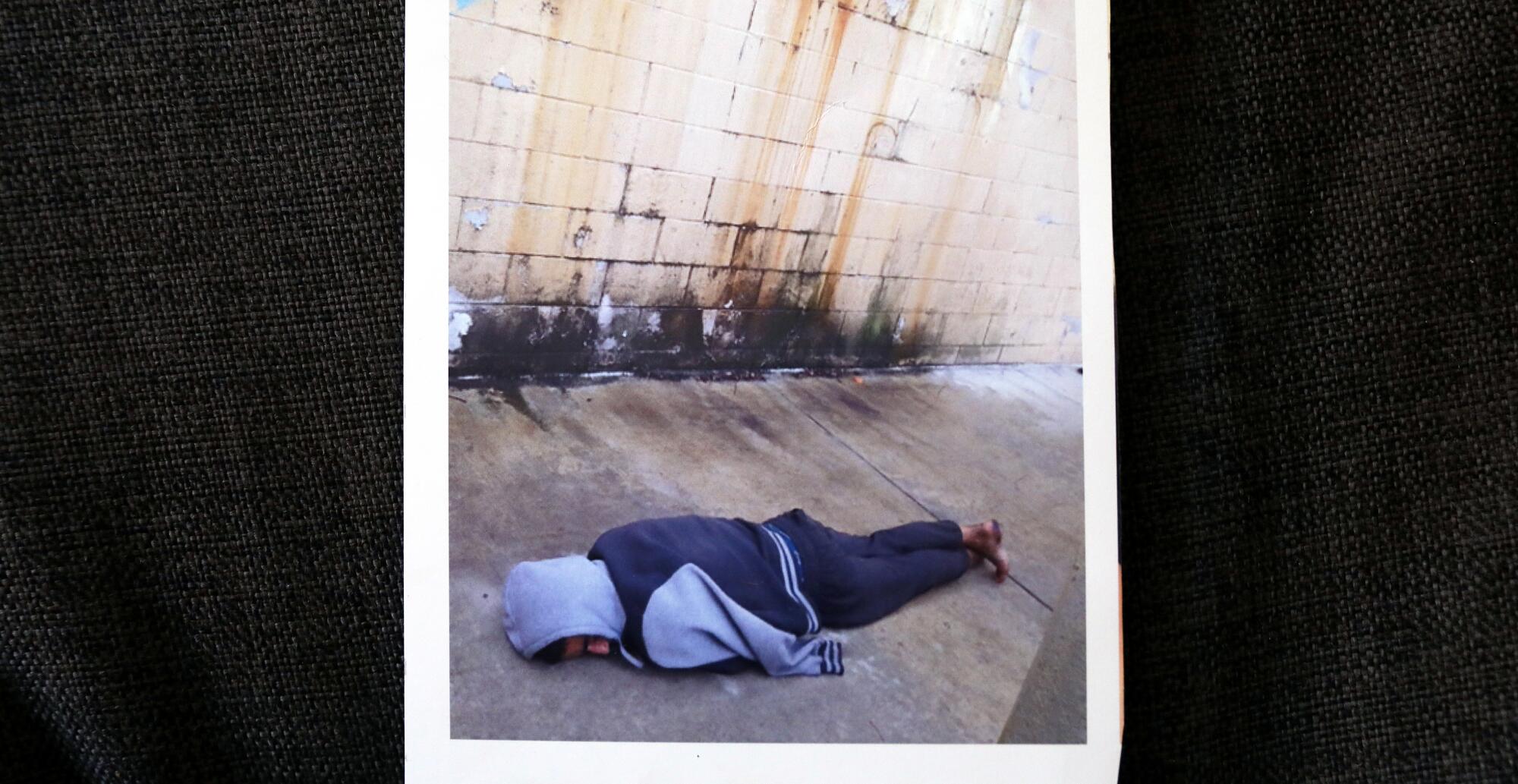

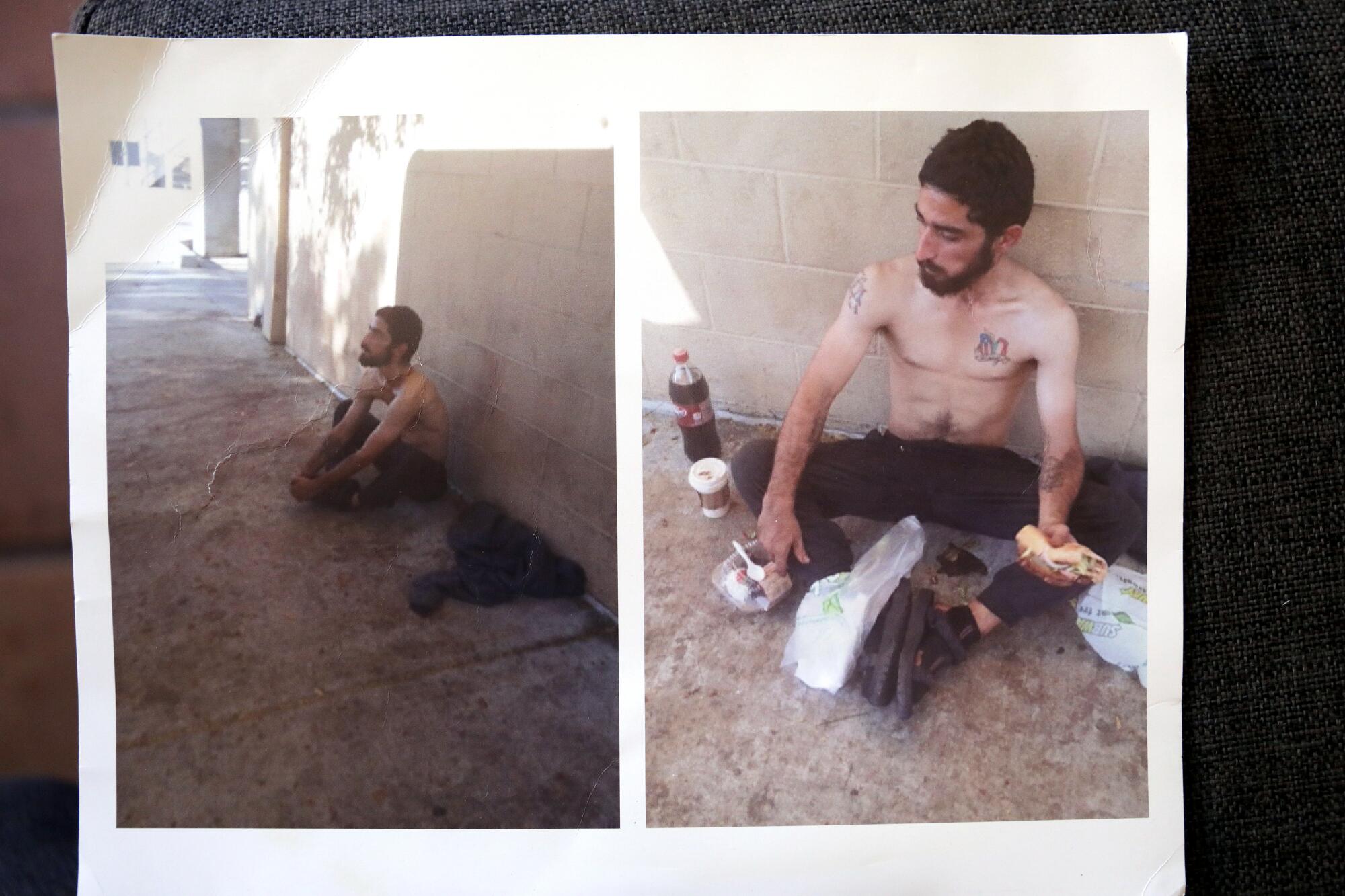

One day, Mary found him face-down on a sidewalk, hoodie over his head, the naked soles of his feet black with dirt. She woke him with some food, and he propped himself up against the wall of an Albertsons and feasted.

They celebrated his 24th birthday on the street.

Years ago, Anthony would have been committed to one of 14 mental hospitals in California. These asylums were the hope of psychiatric professionals who believed that “mentally disordered persons” could be treated in an institutional setting. By 1955, 37,000 people with severe mental illness lived in these massive state facilities.

Inhumane conditions — worsened by overcrowding and deteriorating infrastructure — led reformers in the 1960s to call for closing the hospitals and shifting toward community care.

The philosophy held that with new medications and therapy, the mentally ill could be integrated into society.

While the Mental Health Act of 1967, also known as the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, was hailed as the beginning of a new era of psychiatric rehabilitation, legislators failed to adequately fund smaller county-run facilities.

“The great failure of public policy over the last 50 years is how we discharged people from mental hospitals with no replacement,” said Andrew Scull, a sociologist at UC San Diego who studies the history of mental illness and its treatment.

The burden of caring for the mentally ill fell largely upon families left to navigate a complex system of public and private treatment facilities that are “ill-designed to help them,” Scull said.

The worst off ended up on the street, subject to Section 5150 of the state’s mental health law, which allows forced hospitalization for those considered a risk to themselves or others or those who are “gravely disabled.” For many families, neighbors and social workers who have watched as psychoses and homelessness overlap, that sets the threshold for action too high. The CARE Act, which the state plans to begin implementing next fall, aims to be a step toward remedying this.

Once hospitalized, patients are often treated with antipsychotic medications that eliminate their worst symptoms. Eventually, severely ill patients under extended involuntary holds — with no family to take them in — are transferred to long-term care facilities, referred to as Institutions for Mental Disease, where treatment is less expensive than in hospitals.

Treatment includes medication management and group activities. Neither are compulsory, and staff members encourage compliance through an incentive system with privileges, a marked change from the era of treating mental illness with more brutal and often harmful interventions.

If patients gain insight into their condition, understand their medication needs, maintain daily hygiene and appear sociable, they can be discharged to unlocked facilities, referred to as board-and-care homes.

When a board and care closes, precious affordable housing vanishes — sometimes turning residents onto the streets. Critics say leaders in Sacramento have not done enough to support the homes.

These privately owned homes play a critical role, housing individuals who would have no other place to live, but they form a weak link in the mental health system, said Neil M. Gong, assistant professor at UC San Diego who studies the sociology of mental illness. They are minimally staffed by people who are trying to do their best with minimal funding, said Gong, who has visited a number of board-and-cares for his research.

“They can’t be real homes or provide much care,” he said.

Sheriff’s deputies caught up with Anthony in 2016 for skipping three arraignments on the misdemeanor charge of panhandling in Pico Rivera. They took him to the county’s largest mental health facility: the Twin Towers jail in downtown Los Angeles.

The district attorney’s office eventually dropped the charges, and deputies issued an involuntary hold rather than release Anthony to the street. They took him by ambulance to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Anthony arrived “gravely disabled … with no viable plan of self-care,” the psychiatric staff wrote.

They searched him. They asked him to take off his clothes and put on a gown. He twisted up his face. He refused to take a shower. He thought he was surrounded by cyborgs.

“Who’s president?” they asked, writing down his response.

“Washington.”

They called his mother, who hadn’t seen him in nine months and thought he was dead.

“Please help me save my son’s life,” she said.

They wanted to give him medication, but he yelled at them — “I don’t need this poison” — and pulled a blanket over his head.

Days became weeks. They listened and took more notes.

They told him that his mother wanted to be his conservator. “Whatever,” he said, and they escorted him to court.

With the medications coursing through his body and brain, the voices became less loud, and by the end of January 2017, staff told him that they were trying to find a place for him to live. They mentioned a few facilities. He said he didn’t care, as long as he was allowed to smoke.

The next month, Anthony arrived at La Casa Mental Health Rehabilitation Center in north Long Beach. Staff asked what his goals were.

“Success, money and to be an RN,” he said, adding that he looked forward to taking classes like computer skills, Bible stories, music and medicine.

At first he needed little encouragement showering or taking care of himself. But slowly he began to fall back upon old habits. He started smoking marijuana with other residents, and eight months into his stay, he climbed the fence surrounding the outdoor patio.

“I’ll be back,” he said and dropped to the sidewalk.

Because La Casa is a treatment center, it has no security guards, and the staff, trained in crisis intervention, do not try to stop anyone from leaving, which could lead to injury.

Anthony bought cigarettes and beer at a nearby Shell station. When he returned, he was put on restrictions.

Two weeks later, he slipped out again, returning late at night. He was found sitting near the entrance, sick to his stomach. Beer again. He said he had been drinking forties.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I can’t help it.” God had told him to.

His medication was adjusted, and then smoking was banned. A nicotine patch didn’t cut it. The next time he got out, he scored some crystal meth. A drug test confirmed it.

After that, the voices seemed only to get louder and more demanding. After a treatment team meeting, he got out again and picked up three 32-ounce Miller Lites and some Newport menthols.

Bea and Edward Stricklan’s son has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. The brain disorder is treatable, but accessing adequate treatment has been difficult, if not impossible.

Staff found him and talked him into returning. But he stayed only half an hour before he climbed the fence for the last time.

By spring 2018, Anthony, now 27, was living somewhere in Compton. Mary had to find him. She and a friend drove the alleys and visited homeless camps. They passed his picture around until one women recognized him.

“He’s a little off, right?”

They were directed to a McDonald’s, and within an hour they saw him crossing the street, oblivious to the cars. His pants were torn, his beard long, his hair grown out. He was smelly and filthy, and when Mary tried to reach out for him, he pushed her away.

“I’m a grown man, Mom. Leave me alone,” he said, walking to the stoop of a day-care center, where he fired up a glass pipe and drew smoke into his lungs.

Mary called the sheriff’s station, as she recalled, but they said there was little they could do. If they arrested him, he would be back on the streets within hours.

She broke down in tears.

Two weeks later, deputies did pick him up. They had received complaints that he had exposed himself to children, that he had nearly been hit by a car. They put him on an involuntary hold and took him back to Harbor-UCLA.

For six weeks, doctors chased his symptoms with different medications — Risperdal, then Haldol, then Klonopin, then clozapine and finally back to Haldol — before they started to see an effect.

“I’m a new man,” he said, once they were able to control his tremors, a side effect of the drugs.

Mary brought him fresh clothes and popcorn. He showered and trimmed his beard. He played Yahtzee, shot hoops, did yoga. He talked about working again, helping Dan. He started to ask when he could leave.

As the hospital put together a discharge plan, Mary visited a few facilities. She wanted him to be close to home, and eventually he was readmitted to Meadowbrook.

On a quiet residential street in Mar Vista, Meadowbrook houses 77 men and women, most of whom are schizophrenic, who range in age from their early 20s to early 60s. The locked facility is owned by three limited-liability companies, one of which goes by the name Meshuga Operations Holdings LLC — Meshuga, Yiddish for crazy. The company has ownership interests in four other facilities in Southern California that have contracts with the county Department of Mental Health.

Anthony has lived there since January 2019. He says it’s boring: “I just smoke and sleep.”

He describes waking up at 6 every day and getting his first round of medication. He takes clozapine twice a day and then more pills to counter the side effects of the clozapine, his medical records show.

Breakfast, he says, is served at 7:30. He likes two oatmeals and keeps to himself. He works out twice a day and is proud that he can press 55 pounds.

He has two roommates but no friends. Watching television gives him a headache.

Meadowbrook encourages residents to attend group meetings on topics such as memory and concentration, anger management, conflict resolution, medications and current events.

Mostly, though, Anthony, by his own account, walks up and down the halls, drinks coffee, gets an occasional Twix from the vending machine and smokes on the back patio: two cigarettes a day, one in the morning, the other after dinner, which is served at 5 p.m. He is in bed by 9.

A mental institution in Mar Vista, built originally as a developer’s home, spans the modern history of West Los Angeles and the region’s halting efforts to house the mentally ill.

If the goal for treating individuals with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia is independent living, then progress has stalled at medication and confinement with little focus on long-term management.

“We still see psychiatric illness too narrowly,” said Dr. Joel Braslow, a professor of psychiatry at UCLA. “We still hold on to the 19th century model of mental illness, as if it were a bacterial illness” — as if once treated, it’s cured.

Severe mental illness is not simply misdirected electrical impulses in the brain, he said. It is also the confusion, distress and social isolation, which also require treatment.

“We need to understand that the suffering brought on by these disorders is not just biological, but also psychological and social,” said Braslow. “Our definition of treatment should extend far beyond medical management.”

“People need help with things like going back to school, maintaining a good relationship with friends, or dealing with social phobias not just in therapy at the clinic, but by going out to a restaurant with a case manager,” Gong said.

Psychiatric rehabilitation comes down to “people, place and purpose,” said Sherin: medical services alongside family support, a home and reason to get up in the morning.

Anything short of that, writes Scull, is abandonment of “a collective moral responsibility to provide for the unfortunate.” It is, in other words, warehousing.

Since the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions, Mary has tried to visit Anthony regularly. Over tacos and a decaf, they sat in Meadowbrook’s fenced-in patio. On other visits, she took him to Venice Beach. They practiced tai chi in a local park, hiked through Temescal Canyon with his father, rode bikes and had a backyard barbecue with his sister and her daughter.

The reunions were rewarding and frustrating. He seemed to be improving, but he needed supervision. Without monitoring, she could see him drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes all day.

He had been at Meadowbrook for more than three years; most patients transition to board-and-care facilities after two. The pandemic had slowed progress, but Mary wanted to know what steps were being taken to prepare her son for eventual discharge.

Four times a year, members of the Meadowbrook staff and a representative from the Department of Mental Health meet with Anthony and Mary to discuss the treatment plan.

When the call came in for one of those meetings earlier this year, Mary put her phone on speaker so she could take notes.

After the staff recounted his medical history and a little good news — because of his increased participation in groups, Anthony had been named Resident of the Month — Mary got to the point.

“Do you see Anthony living independently?” she asked.

“Not at this time,” someone said.

For a moment, Mary said nothing. She felt the pain of seeing her son locked up, but there seemed to be no other choice. As grateful as she was for their help, she wondered if they were doing enough, but she worried about asking too many questions or appearing antagonistic. She depended on them for Anthony’s care.

With the meeting almost over — her questions partially answered — she wanted to remind them of her continued commitment to his recovery.

“I want to be a partner in Anthony’s mental health, and I want us to work together,” she said, “and I don’t want him to be just discharged. My biggest fear is him ending up homeless again, so I want a concrete plan, and I really hope that we work together for that.”

“Absolutely,” came the response, and after 20 minutes, the meeting ended.

In silence, Mary sat at her kitchen table, a cool breeze coming from the open window, and Anthony returned to his room, to the voices who still whispered in his ears, still crowding out the world he remembered: the world of his childhood, his family, his mother and his sisters, the world before everything became incomprehensible.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.