A toast to the misunderstood temperance movement on the anniversary of its demise

- Share via

Eighty-nine years ago this week, another of our long national nightmares was over.

For 13 luckless years, the United States of America went piously, officially “dry,” banning by constitutional amendment the vice of liquor — and paradoxically plunging itself instead into an age of reckless, lawless drinking, organized crime and hypocrisy so blithe that the president of the United States poured booze at his White House poker parties and stashed a bottle of whiskey in his golf bag so he could sneak a snort before he hit the links.

It took a second constitutional amendment to undo the first, and we still have not undone the disorder it all left behind.

The toxic legacy is so deep that it’s easy to forget the high purpose that created this ill-starred undertaking in the first place.

That was called the temperance movement — temperance, which could mean both moderation in drinking or a complete teetotaling ban. America’s Prohibition chose the latter.

It emerged in part from the deeply held moral conviction that Americans are a better, finer people than citizens of other nations, and so our habits and practices should be better and finer than theirs too. If you created a Venn diagram of 19th century social movements, you would find hefty overlap among the crusades for temperance, for the abolition of slavery and for women’s suffrage.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

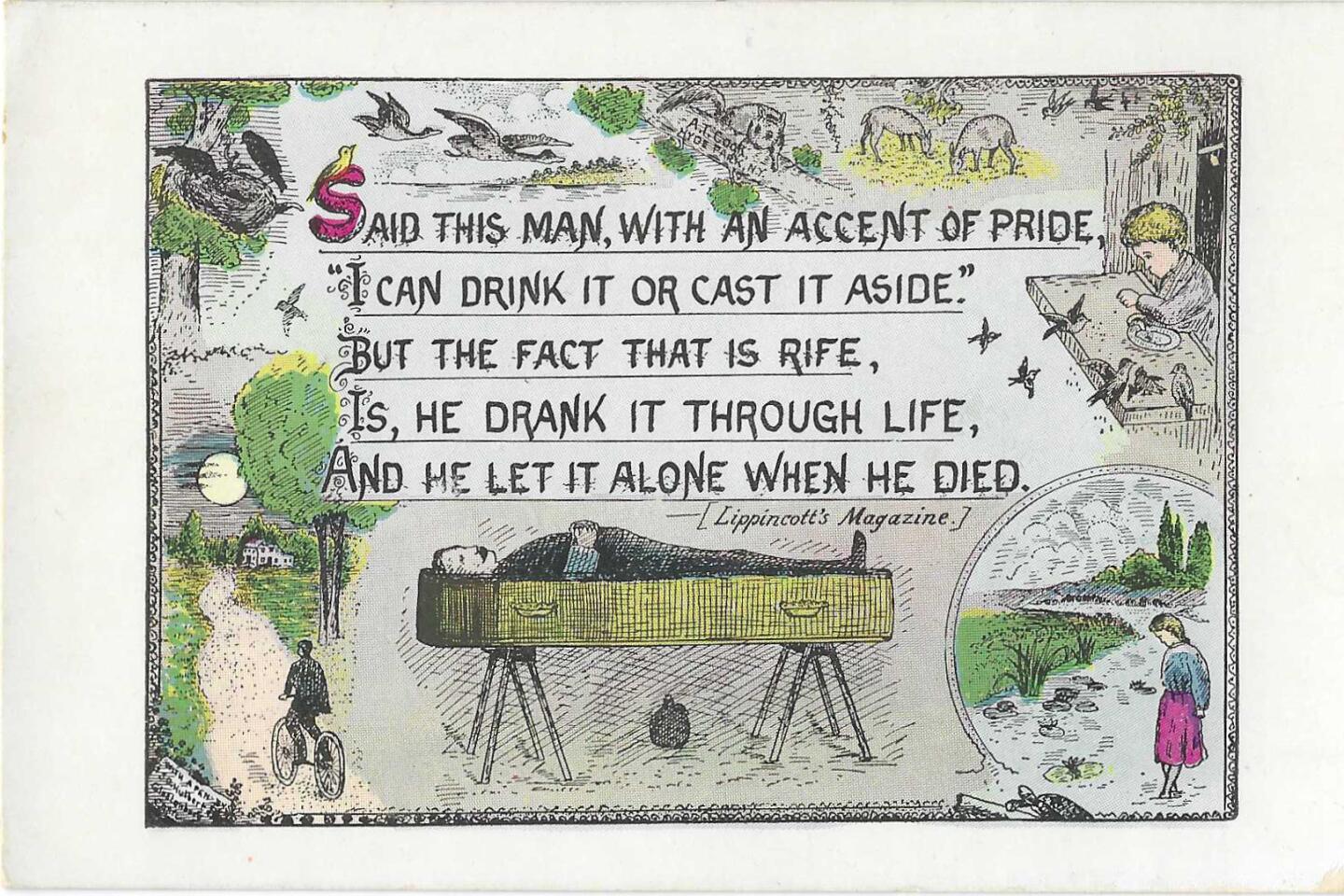

The temperance movement had legitimate, even life-and-death reasons for doing what it did. Then and now, temperance crusaders were lampooned as hatchet-wielding, hatchet-faced, uptight spoilsports, zealots who smashed up barrooms and beer halls and in general wanted to stop men from having a good time.

But in fact, a number of men were having too good a time, or were having a dreadful time and drinking to forget their misery.

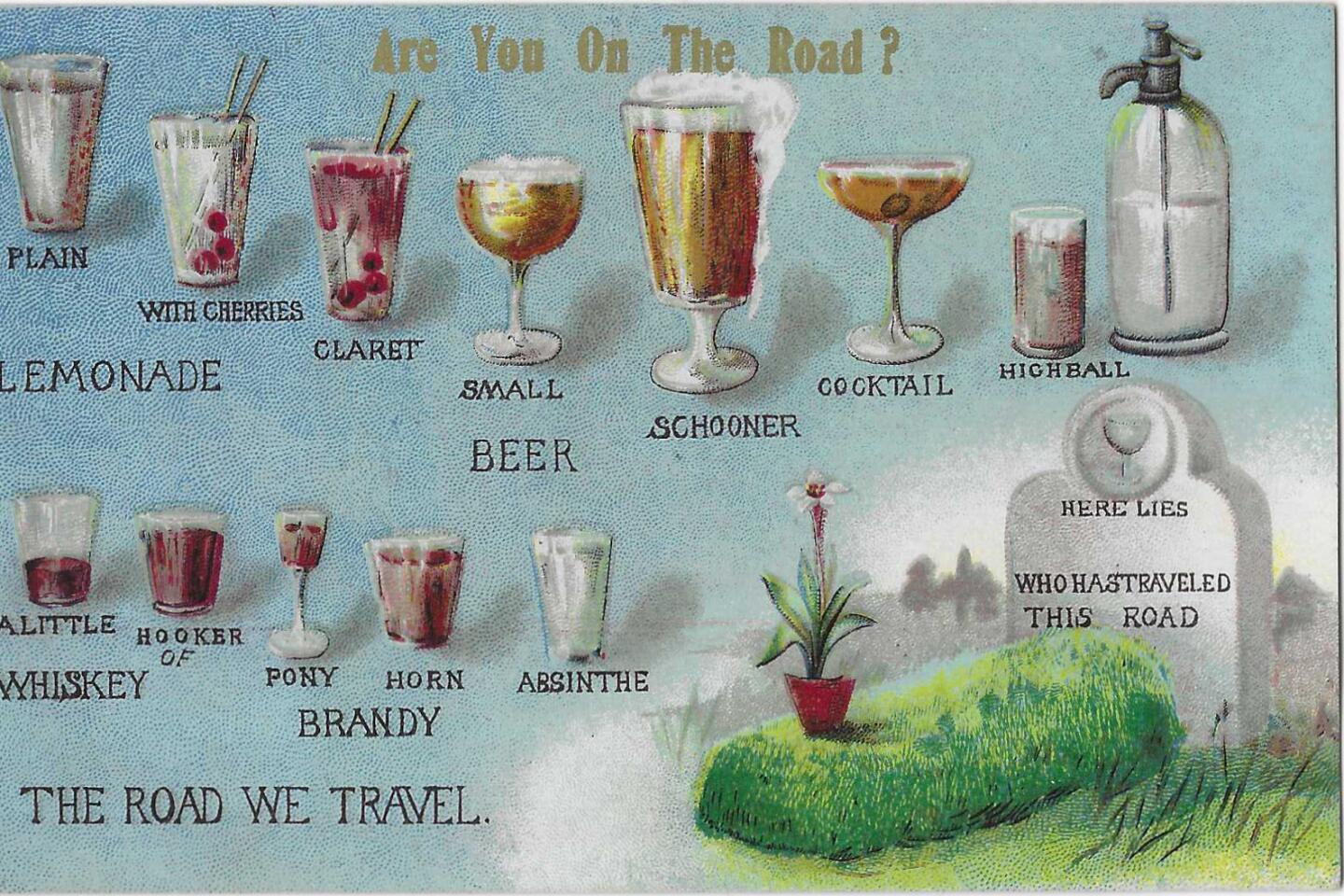

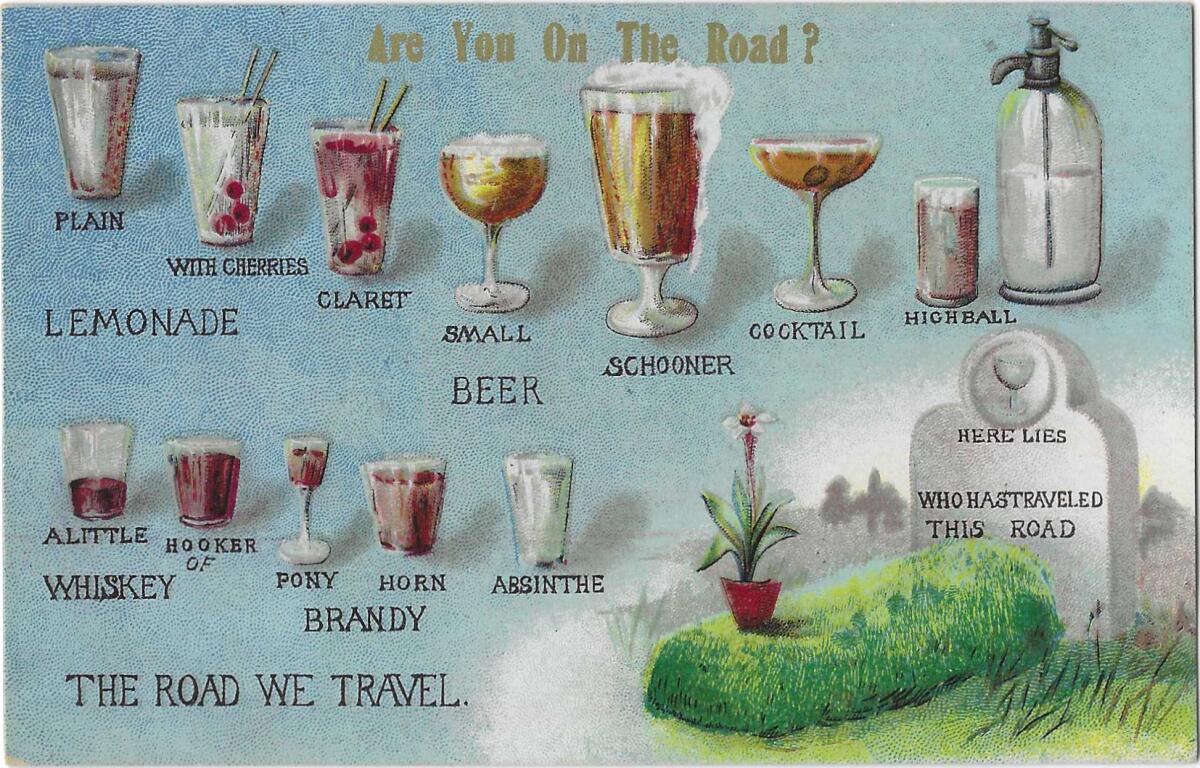

Americans drank — a lot. In 1830, as the temperance movement was finding its voice, drinking-age Americans, mostly men, were knocking back about seven gallons of liquor every year — about three times as much as today’s average of about 2.45 gallons.

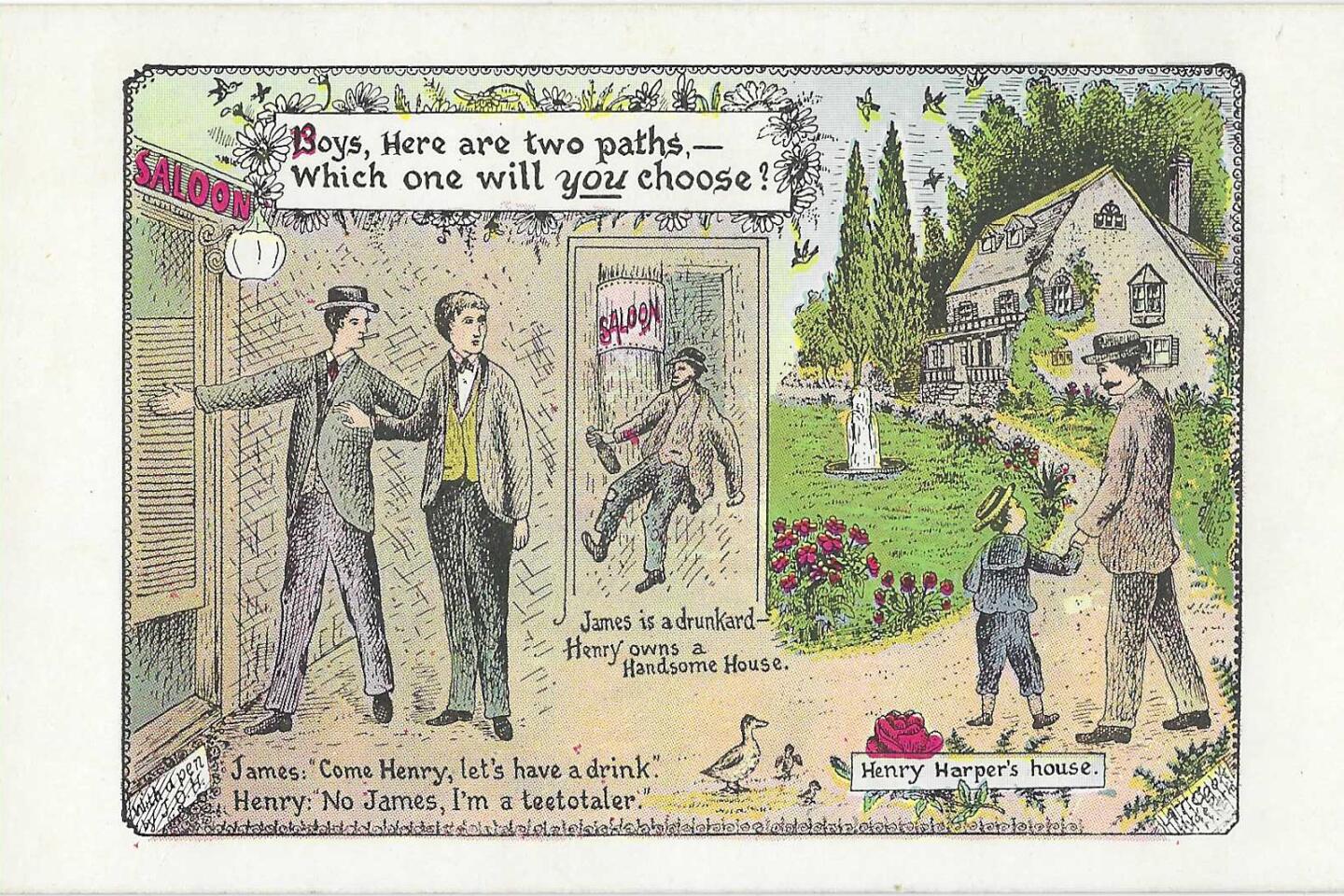

They drank at work. They drank in saloons and in beer gardens. They drank alone, and in company. And, maybe worst of all, they drank on the way home on paydays. By the time they got back to the little woman and the kiddies, they’d drunk away a good part of the paycheck.

And so the rent went unpaid, and there wasn’t enough money left for food, or fuel, and the kiddies went without things they needed, and sometimes the drunken husband beat up the wife and cuffed around the kids.

This was becoming a public disgrace, not just a private torment, and around the mid-19th century, courts and the law were just beginning to take wife-beating seriously. But men ruled the roost, and for the woman who did decide to take the kids and leave — well, divorce was about as rare as it was disgraceful, and how on Earth was she to support herself and the children when the law still declared that all she owned belonged to her husband, however loutish he was?

The temperance movement put drunkenness at the core of these domestic crises, as a menace to the American home and family; if men would stop drinking, or stop drinking so much, then the violence and mayhem that drunkards brought down upon their families’ heads would, if not disappear, then certainly decline.

Thus, the movement led by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League made theirs a moral crusade for a humane cause. WCTU supporters wore white ribbons of support, just as today we wear colored ribbons for AIDS patients, POWs or Ukraine.

Americans could watch the sin-and-redemption cycle themselves, in five acts. The 19th century play “The Drunkard, or the Fallen Saved” ran for well over a hundred years on stages in every town big enough to have one. In Los Angeles, it ran for 9,477 consecutive performances, from 1933 to 1959, at the Theatre Mart on Vermont Avenue in Hollywood, a building that became the headquarters of the L.A. Press Club, where a good deal of drinking went on. The Times reported that the bibulous actor W.C. Fields went to see the play more than a dozen times, although probably more in the spirit of “This Is Spinal Tap” than as a lesson in moral uplift.

They were formidable campaigners, although the smash-and-shouters got a good deal of the headlines; prohibitionist Carry A. Nation once stormed into the office of the Kansas governor and, jabbing a finger at him, called him a lawbreaker and perjurer.

But persistent lobbying brought results. The Anti-Saloon League’s leader was Wayne Wheeler, an Ohio attorney who as a boy had been accidentally stabbed by a drunken farmhand wielding a pitchfork — the devil’s instrument. Wheeler crafted a temperance tactical strategy of public parades and private political persuasion.

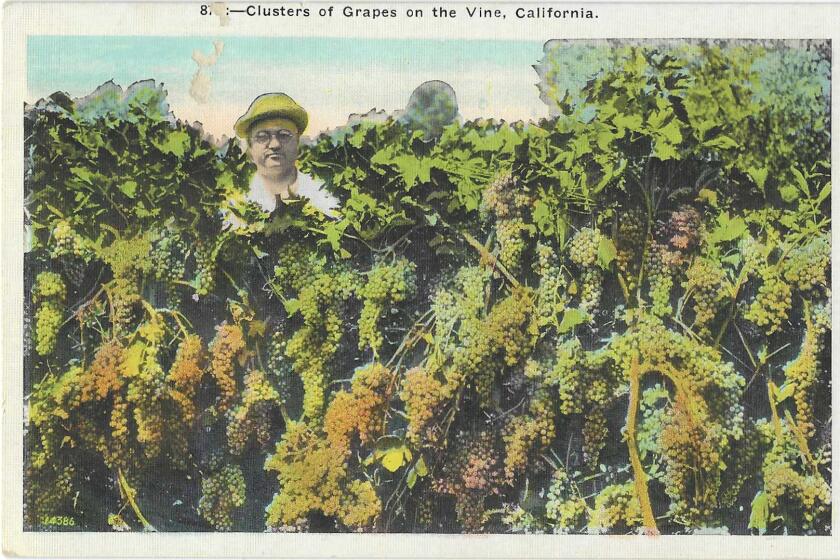

California especially was a prize for prohibitionists. The state was transforming itself from the crude Gold Rush turf of booze and brawls into a new frontier of domestic enterprise, families looking for a new start in a new land. To one temperance leader, California was destined “to be in the future years a second garden of Eden.”

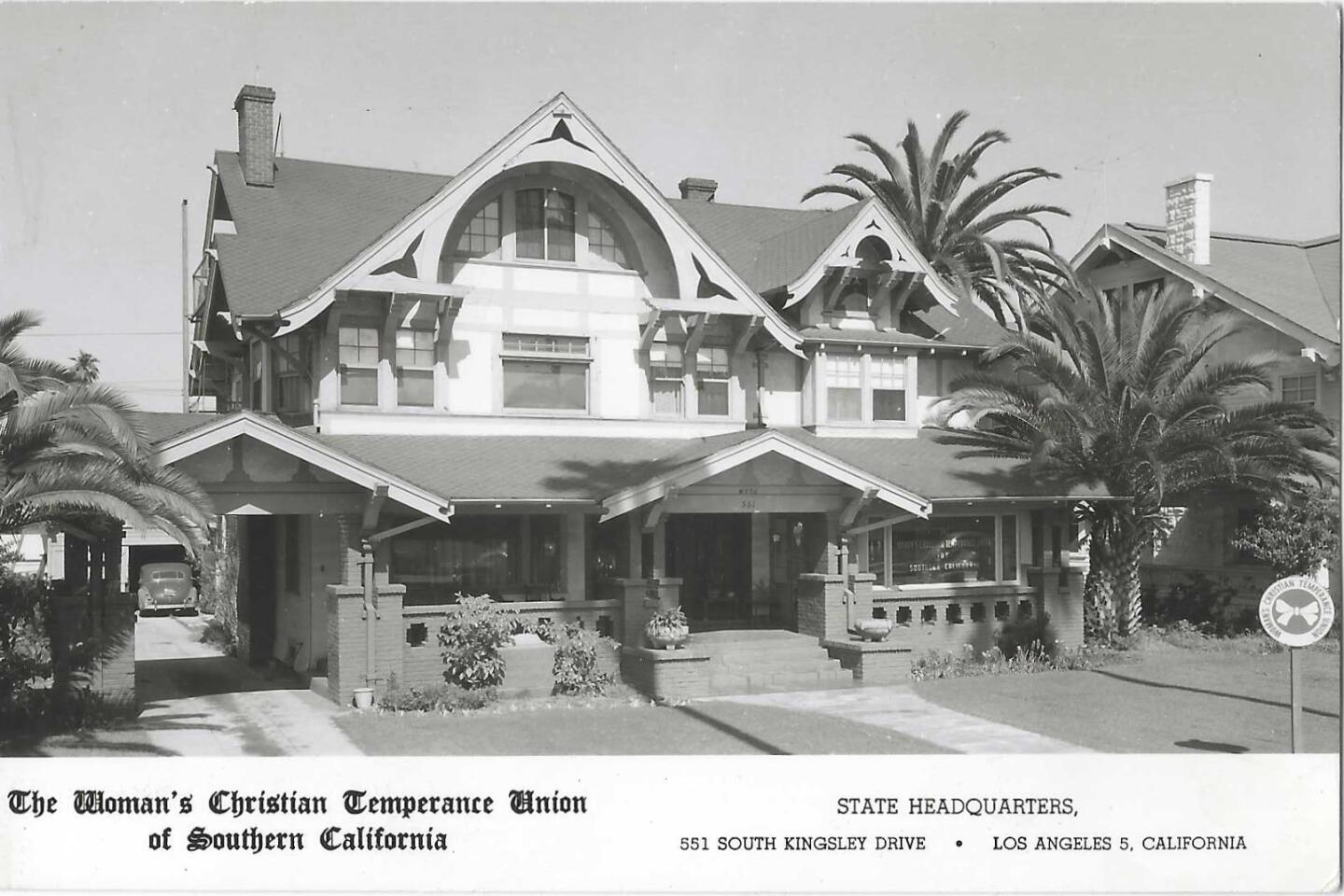

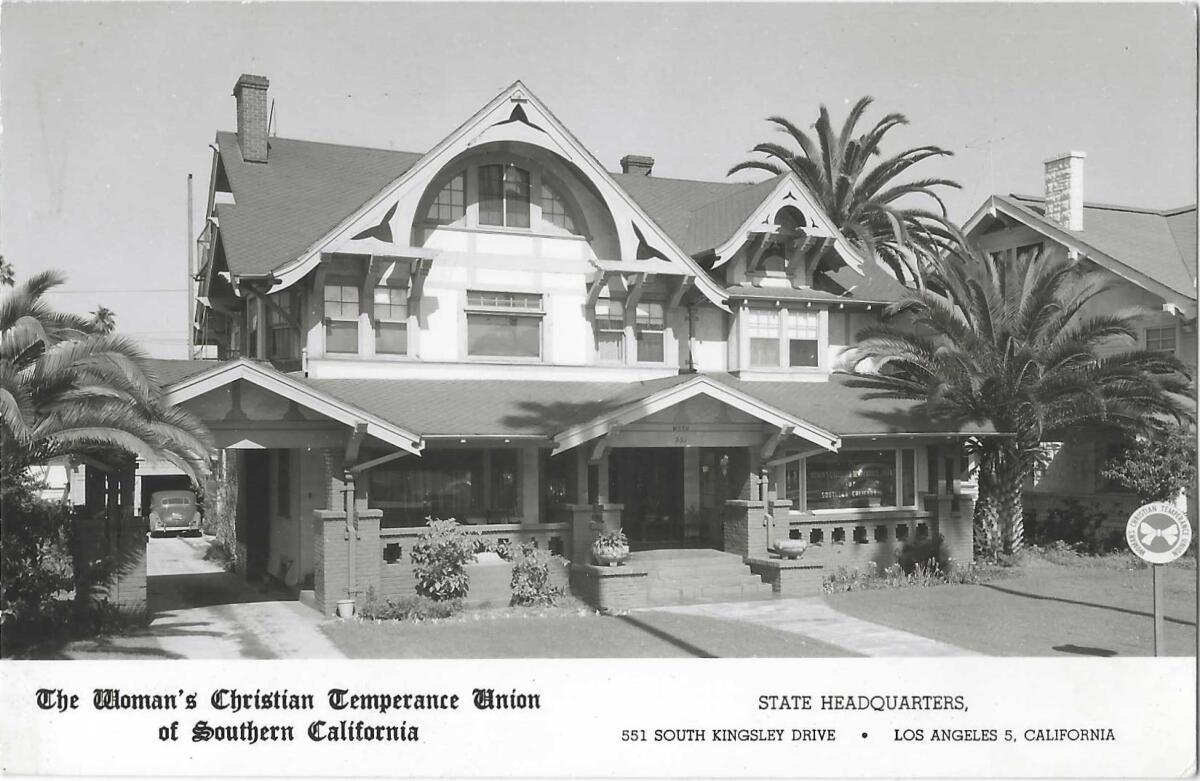

For a time, the state WCTU headquarters was in a house in present-day Koreatown that still stands today, and in 1928 the WCTU opened a home for its elderly and needy members in Eagle Rock, a retirement home that finally closed more than 60 years later. Cal State Northridge maintains a large collection of temperance-related items.

Even the state’s immense wine industry, the WCTU argued, could be easily converted to olives and raisins. In 1929, during Prohibition itself, the national WCTU president was asking for a study of how to keep fruit juice from fermenting. “Eternal vigilance,” she said, “is the price of prohibition.”

The 2011 book “California Women and Politics” totted up temperance successes here: In 1887, the Legislature passed a Scientific Temperance Instruction Law, requiring that schoolchildren be taught about booze and drugs “and their effects upon the human system.” Temperance leaders wanted churches to stop using wine at Communion, and in 1880 persuaded the UC Board of Regents to ban the sale of liquor within two miles of their campuses.

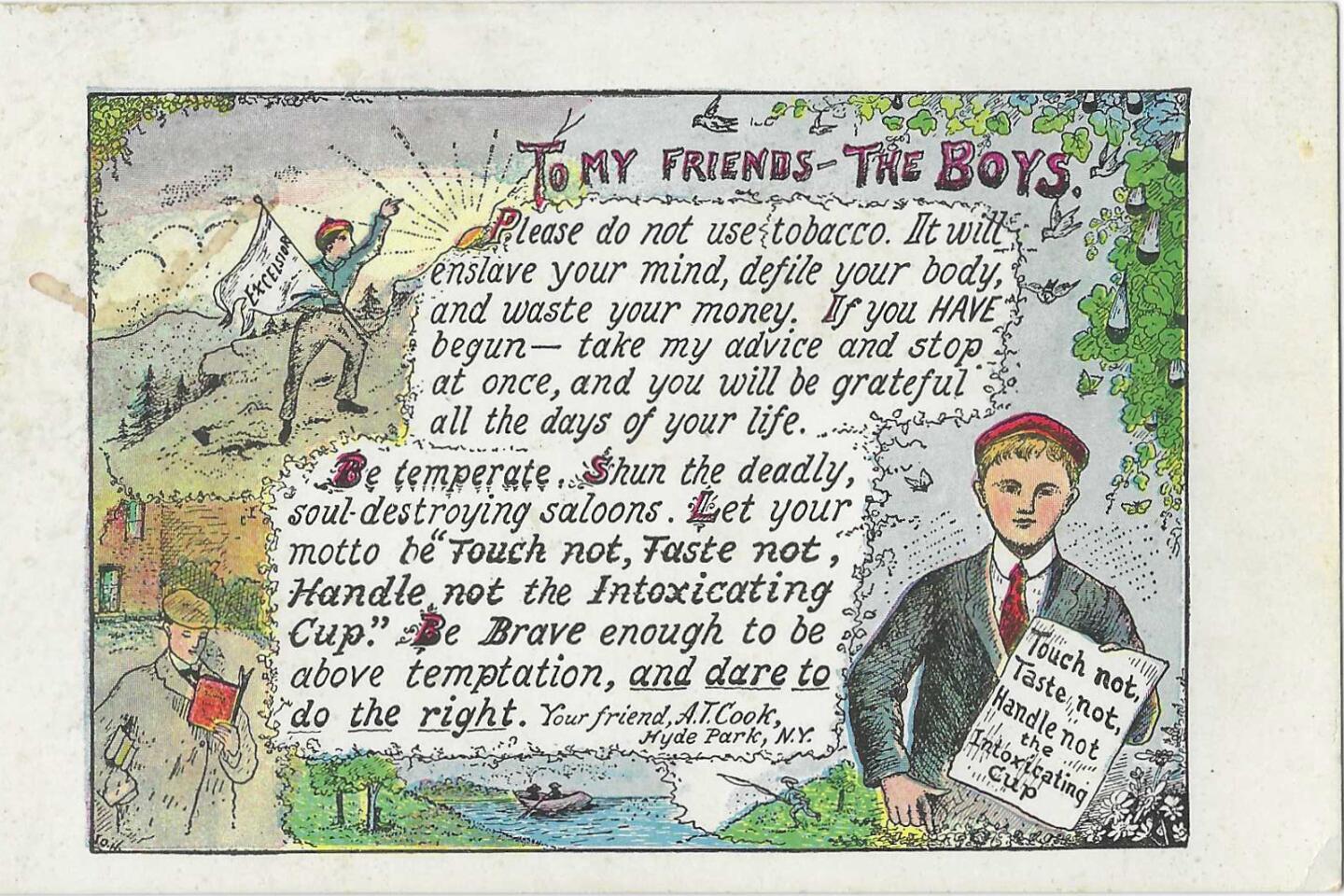

The WCTU evangelized its slippery-slope message to the young. It sponsored student essay contests on the virtues of alcohol abstinence, and crafted “temperance arithmetic” pamphlets that asked students to solve problems like dividing millions of gallons of wine by a certain number of drinkers.

Without a doubt, the temperance movement was created and led mostly by white, middle- and upper-middle-class, Protestant women. Their message did not always resonate with recent immigrants from places like Italy and Ireland, and the movement sometimes singled them out in ugly language, along with people of color, for resisting the call to go dry. But California temperance crusaders were paradoxically more gentle-minded with Asian immigrants — they deplored the “burning shame” of the treatment of Chinese people here.

Next time you raise a glass of California wine, remember the time when Los Angeles, not Northern California, was the state’s major wine region.

And the WCTU walked the walk; it ran coffeehouses and reading rooms to keep men out of barrooms. It offered shelters for prostitutes, abused wives, unwed mothers and their children.

And yet the press and the publicity machines of the liquor trade mocked temperance supporters as scolds and crones. Drunks, on the other hand, were comical, and inebriation a joke — what could be funnier than a sot making his way home and offering beer to the streetcar horse?

In January 1915, Los Angeles’ first female council member, Estelle Lawton Lindsey, was made acting mayor for a day. Were she a real mayor, she told the papers, she would “establish a blacklist for drunkards to be placed in every saloon and compel saloon keepers to refuse to sell drinks to anyone on this list.”

Running scared, the same industries and tycoons that were fighting against giving women the vote — the liquor business and the tobacco and gambling lobbies — dug in their heels against Prohibition and its temperance idealists. Imagine, all those women voting in a bloc and banning those gentlemanly delights, as well as child labor and other profitable abuses!

Many threads wove the fabric — or the rope — of the 18th Amendment, Prohibition. During World War I, the constitutional amendment swept through the states and Congress like a purging auto-da-fe. Fighting in Europe’s “war to end all wars,” young American soldiers were the saviors of civilization, and the country they called home should purify itself to be worthy of its new status as the leader of nations.

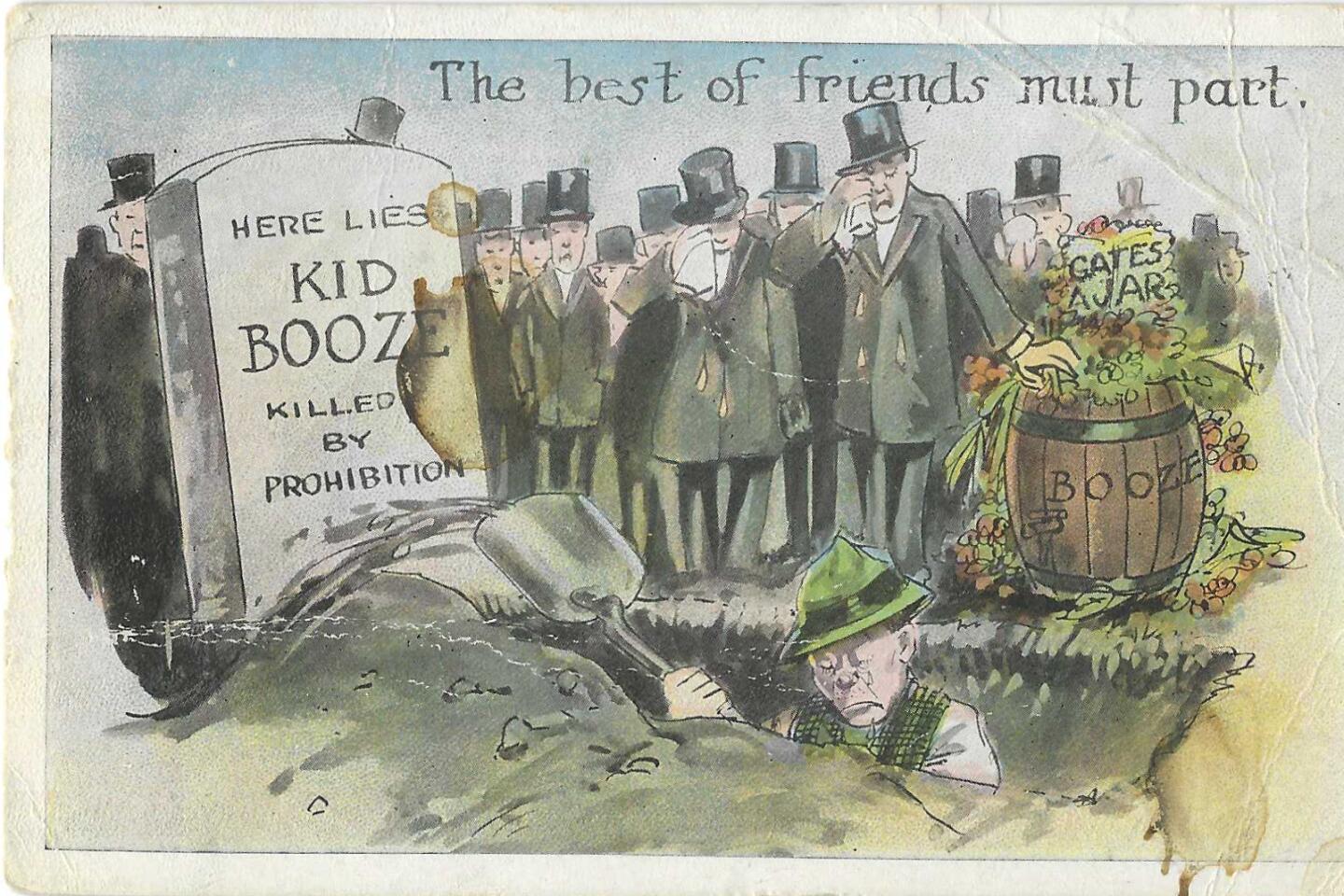

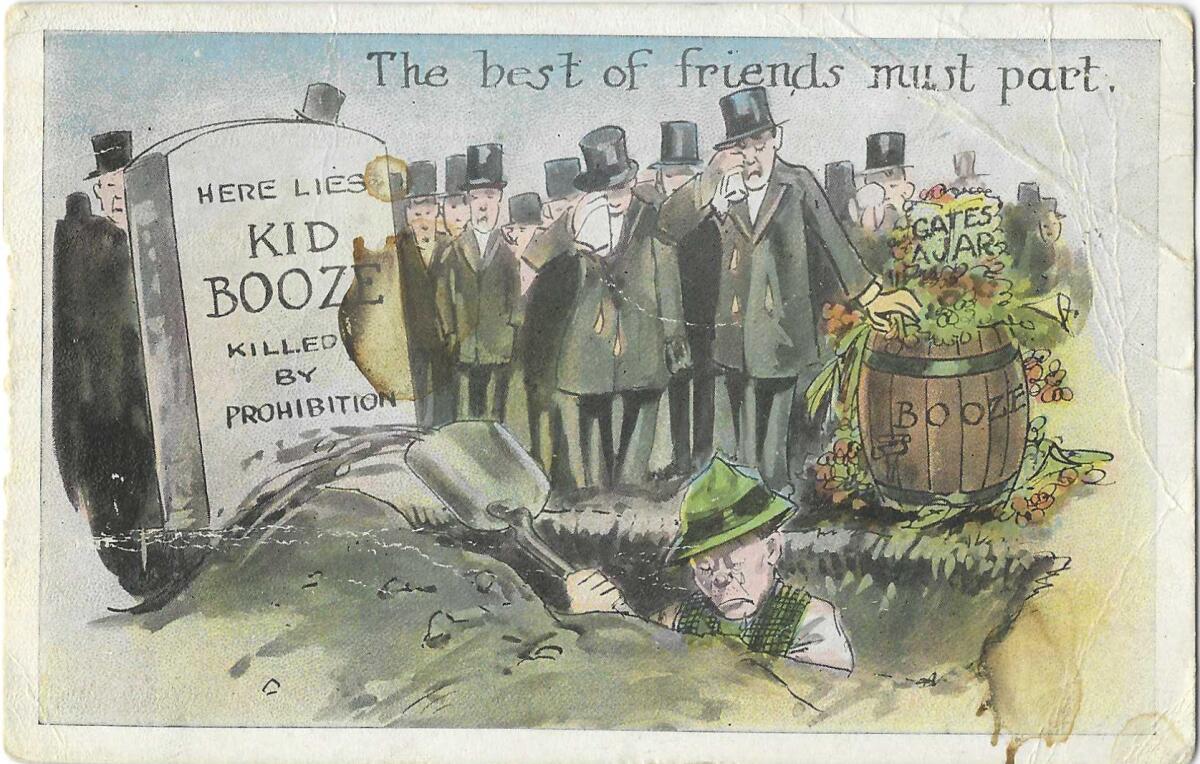

In Norfolk, Va., on the January morning in 1920 when Prohibition became law, the renowned evangelist Billy Sunday staged a mock funeral for liquor. “The reign of tears is over,” he preached. “The slums will soon be only a memory … men will walk upright now, women will smile, and the children will laugh.”

His new Jerusalem never happened. In trying to undo one evil, Prohibition created another, many others. The crime wave of bootlegging generated a gangster class and civic corruption to go along with it. Prohibition made criminals of ordinary Americans just wanting a glass of wine or a stiff drink now and then.

In December 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th. Even some temperance supporters acknowledged that the “noble experiment” had to come to an end, and the enticing argument that taxes on liquor would be a boon during the Depression helped the repeal to win the day.

Anti-drinking sentiment still exists, perhaps most successfully with the influential MADD organization, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which focuses on drinking and driving. It marks each holiday season by asking designated drivers to display a red ribbon on their cars.

For decades after the repeal, some states stayed in the “dry” column. This national patchwork meant that airlines had to suspend liquor service for the minutes that the planes were flying over “dry” states such as Pennsylvania. In the 1970s, Kansas Atty. Gen. Vern Miller demanded that airlines flying over his state stop pouring liquor in Kansas airspace. A year before, Kansas had arrested three people in a raid on an Amtrak train that was still serving drinks as it passed through Kansas.

In 1939, five years after Prohibition’s repeal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt welcomed Britain’s King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to the White House with a Champagne toast. The head of New Jersey’s WCTU tsked tsked this festive quaffing; had FDR done that six years earlier, she said, it “would have been cause for impeachment.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.