- Share via

The desperation pervading Los Angeles County’s juvenile halls can be distilled into a single incident and its aftermath.

A veteran probation officer — too afraid of retaliation to reveal their name or gender — was so overwhelmed by the staffing crisis in the facilities that house the county’s most violent young offenders that they begged to be demoted so they wouldn’t have to go back inside.

The officer had been left alone as a fight broke out among more than a dozen youths. When they radioed for help, none came. The officer had to use chemical spray to stop the brawl — a controversial tactic the department was supposed to phase out after officers were accused of excessive force years ago.

The man who painted the devastating scene was Adolfo Gonzales, chief of the L.A. County Probation Department, according to documents reviewed by The Times and a person who was present for the conversation. His audience: a September meeting of the department’s top directors.

It was just one example of what many describe as the daily disarray inside L.A. County’s juvenile halls. Dozens of officers are either on long-term leave or refusing to come to work, creating a staffing crisis that has led to increased violence in the halls and fostered an atmosphere many say is unsafe for the youths the county is tasked with caring for.

Of the roughly 1,200 jobs available in L.A. County’s two juvenile halls, 40% are filled by “able-bodied” probation officers, people who can physically interact with kids, according to the department. Roughly 27% of juvenile hall employees, or 329 officers, are out on leave or on “light duty.”

Between 30 and 50 officers are calling out per shift, according to a letter Gonzales wrote to the L.A. County Board of Supervisors in September. The situation is so desperate that the department in October began offering increased base and overtime pay for any officer who simply shows up for work.

The Times spoke to nearly two dozen people with direct involvement in L.A. County’s juvenile halls — including probation officers, teens in custody, defense attorneys, medical staff and parents of incarcerated youths — all of whom agree the halls have become unsafe and chaotic over the past seven months. Many of the employees spoke to The Times on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Probation officers have been beaten and suffered broken bones on the job, they said, and the staffing shortage has left some so exhausted that it’s not uncommon for them to resign mid-shift.

Youths, meanwhile, are facing adverse mental health effects from the increased violence and the department’s practice of isolating them to control the chaos. A clinician who spoke to The Times said patients who never exhibited self-harming behavior before have suffered suicidal ideations.

They blame the increased use of isolation in recent months. Lawyers say some teens are taking plea deals against their advice just to get out of the halls.

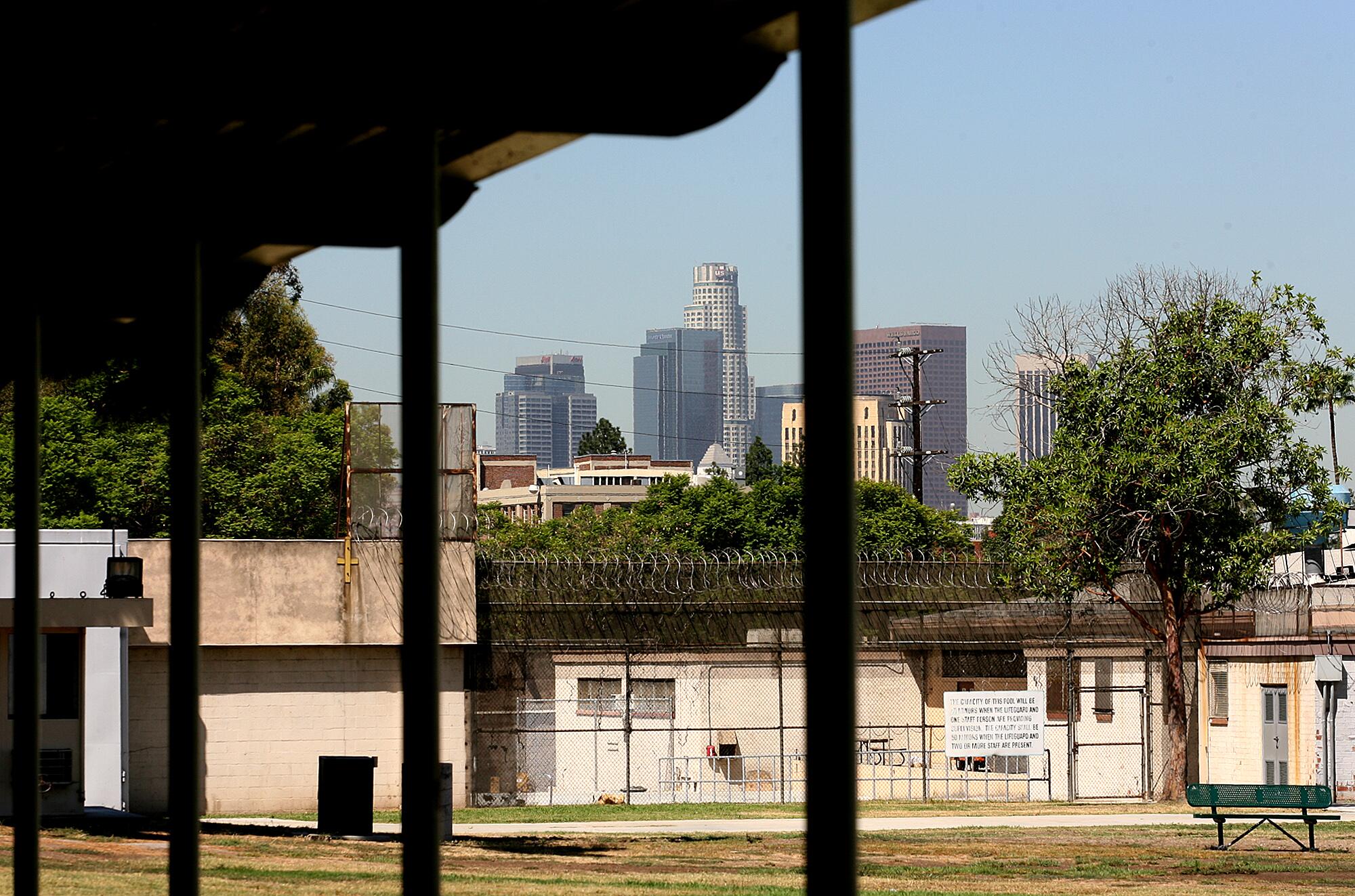

The facilities are run by the probation department, a law enforcement agency tasked with supervising adults and juveniles released from custody on certain conditions. The department oversees two juvenile halls — Central, just east of downtown L.A., and Barry J. Nidorf in Sylmar — and a number of camps.

The halls house about 370 youths, including a small number of people younger than 25 who are awaiting trial for serious crimes, such as murder, or who have been sentenced to the halls because prosecutors did not try them as adults. That population is expected to expand next year after Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to close the state Division of Juvenile Justice goes into effect, worsening concerns about the need to fix the staffing crisis.

Not long after the September meeting between Gonzales and his top deputies, Central Juvenile Hall was placed on “lockdown” because there were not enough officers on site to safely monitor the youths housed there, according to three sources with direct knowledge of the situation.

When a juvenile hall is locked down, youths are isolated in their rooms and denied access to schooling and recreation, sometimes for as long as 24 hours. The use of lockdowns has become increasingly common this year due to the staffing crisis, those officials said.

But as officers tried to enforce that lockdown at Central, one youth reached his breaking point, according to a clinician who was on site that day.

The teen refused to go back to his room and sat at a table in a common area, according to the clinician, who said the juvenile was dragged away screaming by eight probation officers.

As the youth was forced into a room, the clinician said, they heard the teen shouting he “couldn’t breathe” as he struggled with officers. Once locked inside, the teen began smashing his head against the door, but no officers checked on him. It did not appear the youth was seriously injured, the clinician said.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

In the first six months of 2022, the number of times officers used force on youths jumped by 50% compared to the first half of 2021, according to data provided by the probation department in response to a public records request. The number of times that youths were pepper sprayed quadrupled in the same time frame, records show.

Attacks on officers and fights among youths have also increased dramatically. As of Oct. 9, the number of assaults on staff in the halls was already higher this year than the total alleged in all of 2021, according to probation department data. There had been 1,268 fights in the halls as of Oct. 9 this year, compared to 794 in all of 2021, a spike of 60%, records show.

For the record:

9:38 a.m. Nov. 28, 2022An earlier version of this article referred to Chief Deputy Probation Officer Karen Fletcher as deputy probation officer.

Gonzales, who joined the department in February 2021, declined to be interviewed for this article. The probation department sent a five-page letter written by Gonzales and Chief Deputy Probation Officer Karen Fletcher in response to a list of questions from The Times.

In the letter, the officials said they inherited many of the problems the department is facing from a prior administration, but that they have a plan to restore the agency.

“Our long-term plan is straightforward: To demonstrate the Department is capable of substantial change and improvement,” the letter read. “Once we solidify the gains under our emergency measures, our goal is to stabilize the staffing situation and make structural changes to allow the County to transition from a traditional detention approach to the ‘L.A. model,’ which emphasizes collaboration with community partners to provide therapeutic programs in a home-like setting of small groups.”

The pay incentive plan, Gonzales said in the letter, has led to an increase in the number of employees showing up to work at both halls. The department expects to push an additional 150 officers through academy training by January; 17 of those recruits had their first day of training in late October.

But those who work in the halls don’t want to hear about a long-term plan. They say they are facing a crisis now.

“Somebody is going to die,” said a veteran supervisor at Central Juvenile Hall. “I promise you that.”

Many of those who spoke to The Times say the situation inside the halls began to spiral out of control in March, after the rushed, disorganized transfer of 140 youths from Central to Nidorf.

Days before an inspection by the Board of State and Community Corrections — which oversees conditions in correctional facilities in California — a review of video footage found that some probation staff were not conducting safety checks on children who were left alone in their rooms, two high-ranking probation officials told The Times.

Fearing a failed inspection would lead to Central’s closure, the probation department ordered a 90-day “suspension of operations” and directed the entire population of the hall to be moved to Sylmar.

A veteran Central supervisor said discussions were held about moving the kids in waves one week before the actual transfer. But those plans never materialized.

“I get a call that morning saying: ‘Hey, we’re moving them today.’ … It was just an entire mess,” the supervisor said. “We were told that BSCC wants these kids out. If they’re here on Monday, then we’re not going to pass the audit.”

Tracie Cone, a BSCC spokeswoman, denied that the board ordered the probation department to conduct the transfers.

What followed was “complete chaos,” the Central supervisor said. As the probation department placed nearly every youth in its custody into a single building, the mixing of the two populations quickly sparked violence, according to several officers.

‘I get a call that morning saying ‘hey, we’re moving them today.’ It was real piss-poor planning.’

— One veteran supervisor at Central Juvenile Hall

Angered and unsettled by the transfer, youths hurled fire extinguishers, smashed windows and brawled in a large communal area called a day room, officers told The Times. Urine was splashed in at least one officer’s face, and another suffered a facial fracture, the supervisors said.

Parents showed up at Central to visit their kids only to find they weren’t there, according to several officers and a statement released by L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis.

The probation department has repeatedly claimed parents were properly notified. In their letter to The Times, Gonzales and Fletcher sought to downplay the chaotic transfer and its effect on the halls.

“The issues we’re dealing with stem from chronic problems, and not the transfer in March. It is true that some of our juveniles weren’t fully cooperative, but we had safeguards in place during transport to make sure they were transferred safely,” the letter read.

The probation department also said the transfer allowed it to make much needed repairs to Central, including improvements to cracked sidewalks, the installation of a new air conditioning system and the resurfacing of basketball courts.

While Central is older, the two halls’ basic layouts are similar. Each is broken up into units that house youths by age range in dormitory-style settings. Some youths also are held in “specialized units” if they have disabilities or require “enhanced supervision,” based on the crimes they have been accused of.

Classes are taught in buildings separate from the structures where youths sleep. Both halls have common spaces, as well as outdoor areas for recreation that include pools and basketball courts.

The disruptive nature of the March transfer may be reflected in the increased violence.

The average number of attacks on officers per month jumped from 12 in February to 28 from March through May, records show. The number of fights between youths in custody each month nearly tripled, from 31 in February to an average of 98 from March to May. Officers soon started calling out in droves.

“Some of them are just quitting outright. They’re saying: ‘I’m not going to get assaulted every day,’” the Central supervisor said. “I got a buddy of mine ... after [the transfer] he got punched in the face. His nose was bleeding. He went out on injury for a while, and I got a text that he quit.”

But Scott Budnick — a member of the state oversight body that has found L.A. County’s juvenile halls “unsuitable” to house youths three times in the past year — said that “the probation officers of Los Angeles County need to look at themselves in the mirror and find a different line of work if they can’t do the one they were hired to.”

Central reopened by June, and dozens of young people were bused back. That month, BSCC investigators found the department was still failing to conduct safety checks on teens held in isolation.

In July, a report from the L.A. County office of the inspector general found the department was failing to meet some of the requirements outlined in a 2019 settlement with the California Department of Justice over its treatment of youths.

Use-of-force incidents were not being properly recorded on camera inside Nidorf Hall, according to the inspector general, and some officers were failing to submit reports on use-of-force incidents in a timely manner. The inspector general found all reports on use of force were filed at least a week late, and in two instances, reports were filed more than 100 days late.

Some of them are just quitting outright, they’re saying I’m not going to get assaulted every day.’

— A supervisor at Central

By late July, Nidorf Hall erupted in another spasm of violence. A fight involving 17 youths left windows shattered, door locks broken and at least nine people hurt, according to a a probation department spokeswoman and a memo Gonzales wrote to the Board of Supervisors.

Five officers received treatment for a range of injuries, including a broken hip. Four youths were taken to a medical facility with a concussion, a fractured arm and other injuries, according to Gonzales’ memo.

During a July meeting of the county’s Probation Oversight Commission, Chief Deputy Probation Officer Adam Bettino said the department had lost at least 130 line officers to resignations or promotions in the past fiscal year.

Internal memos and texts from supervisors begging officers to come to work became commonplace. In July, the executive board of the union representing rank-and-file probation officers sent out an alert after half the staff scheduled to work a day shift at Central failed to show up.

“It’s time to rally to save our jobs and our profession,” the memo read.

Weeks later, even high-ranking officials like Fletcher were pleading for help.

“Desperate need for staff at [Central Juvenile Hall],” she wrote in a text exchange with other probation officials reviewed by The Times. “Any volunteers would be great.”

But the absences and departures continued. By mid-August, officers staged a rally outside a Board of Supervisors meeting, booing the supervisors’ names loudly while demanding that the county lift a hiring freeze and get them some backup. Several officers said youth in custody are more dangerous than they were in years past and said they felt their cries for help have been ignored.

“We feel like we have no support. The youths are always painted as the victims,” one officer said. “We need more staff. We need more help. We’re dying here.”

While officers feared for their safety and job security, the youths they were charged with protecting continued to suffer the consequences of those absences.

Sam Lewis, executive director of the nonprofit Anti-Recidivism Coalition and a member of the L.A. County Probation Oversight Commission, said young people thrive when they can develop relationships with probation officers and get on a consistent routine. That has been impossible during the staffing crisis, Lewis said.

“When I say the youth want consistency, that’s not Sam’s words. That’s what the kids say: ‘We want people that come in here and know what our program is,’” Lewis said. “They want to be able to go to school. They want to be able to become the best version of themselves, but they need more consistent staffing.”

Lewis said canceling parental visits and recreation time also has negative effects on a youth’s mental health.

Milinda Kakani, the director of youth justice policy at the nonprofit Children’s Defense Fund, said the probation department staff are creating their own problems. The staff’s refusal to work inevitably leaves kids who are already dealing with trauma or mental health issues cooped up and primed to lash out.

“It’s this cycle where young people are essentially trapped, they have nothing to work toward,” she said. “You’re just left to kind of wallow. You’re left to fester. You’re left behind.”

One teen, who spoke to The Times on condition of anonymity for his own safety, said he’s been subject to at least five 24-hour lockdowns due to staffing shortages since June. He said he spent most of that time “staring at the wall” or writing song lyrics. The room does not have a toilet, and he said officers often ignored his pleas for access to a bathroom.

“It’s like they’ll just stand there and hear it but they won’t do nothing... the other day I had to piss under my door because of them not coming,” the teen said.

The teen said he doesn’t feel he’s being “treated like a human being” and blamed the use of lockdowns for stoking more fights in the halls.

“You’re sitting in a box all day, so it’s just bottled up emotions that’s ready to explode,” he said.

In its letter to The Times, the probation department said it has ordered three lockdowns since March, which involved officers confining “small groups of youths to their rooms on a rotating basis, which allowed some time outside the rooms for recreation.”

“We did this because of low staffing levels; each occasion lasted less than 24 hours,” the department said.

But one high-ranking probation official and the clinician said the department is severely undercounting the number of lockdowns that have taken place since March.

“What is happening is, they are canceling school, recreation and other activities but not necessarily calling it a ‘lockdown’ because it will look bad,” the official said.

‘You’re sitting in a box all day, so it’s just bottled up emotions that’s ready to explode.’

— One teen about the lockdowns

Jerod Gunsberg, a defense attorney who handles juvenile cases, said he’s repeatedly been denied access to his clients due to lockdowns caused by violence. Some of his clients have complained of limited access to showers, haircuts or hygiene products while others have taken plea deals just to get out of the halls, Gunsberg said.

“When you’re not providing basic care, not just from a health perspective but from a self-respect perspective, it takes its toll,” he said. “Kids are basically saying, ‘I will do anything to get out of here as quickly as possible.’”

The probation department and its union believe the answer is to hire more officers, but calls for the Board of Supervisors to lift a hiring freeze have gone unheeded. A motion to do so has been continued twice. It might be taken up by the board in December.

Still, there are serious questions about the department’s ability to manage its resources.

The agency’s budget has increased over the past several years, while the average number of youths in its custody has fallen by more than half since 2020, records show. The bulk of the probation department’s operating costs stem from paying the same staff who now refuse to come to work.

“The answer has often been to give the department more money,” said Nicole Brown, an organizer with the Youth Uprising Coalition. “And yet, the results are only that things are getting worse.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.